Policy Memo

- Details

- Policy Memo

By Babajide Fowowe | Nigeria is currently struggling with a severe crunch in the supply of foreign exchange (forex), which negatively impacts the value of the Naira, its national currency. Both the official and the unofficial forex markets are afflicted by what is basically a liquidity and flow challenge. A number of initiatives and ideas have been mooted which largely relate to borrowing or finding ways to incentivise portfolio flows. Despite supportive oil prices, there is limited discussion around boosting organic forex flows from Nigeria’s oil exports.

Beyond improving security in the Niger Delta to curtail oil theft and re-engaging with capable partners to raise investments in oil production in the country, a short-term and sustainable fix for oil revenue and ultimately for increased forex flows will be for the Nigerian government to immediately cancel the policy of earmarking for domestic consumption a portion (and increasingly all) of its own share of oil output.

Of all the options being implemented or considered for boosting forex inflow into Nigeria, cancelling what is termed Domestic Crude Allocation (DCA) is Nigeria’s surest bet. This will yield immediate result and provide a steady (not one-off) flow of foreign exchange—and thereby address the cashflow challenge in the official segment of the forex markets. Additionally, it will end the dodgy deductions and accounting associated with the domestic crude allocation policy that has been aptly described as an active crime scene.

The DCA has acquired an outsized profile of recent. Any serious attempt at understanding and reforming how Nigeria’s share of oil is accounted and paid for must, for a number of reasons, zero in on the management of and the recent prominence of the DCA.

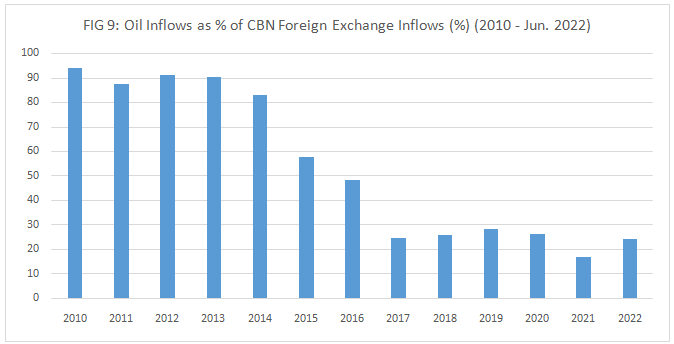

With the drastic reduction in oil production in Nigeria and the shift in production arrangements away from Joint Ventures (JVs) to Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs), most of the Federation’s share of crude oil produced in Nigeria is channelled to DCA, which has dramatically risen from below 10% of Federation’s share of oil in the early 2000s to almost 100% by 2023. This is not just a suboptimal allocation issue. In relation to forex flows, it is a key challenge because the revenue from DCA sales is received in Naira, meaning that the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is starved of steady and healthy flow of foreign exchange from what used to be its dominant source: crude oil sales. As at 2010, flows from oil and gas accounted for 94% of forex to the CBN but plummeted to 24% by June 2022, and is conceivably much lower now (CBN, like NNPCL, has stopped disclosing some critical data).

Crude oil exports still account for over 70% of Nigeria’s total exports but since 2016 an increasingly disproportionate percentage of the country’s share of crude oil exports is earmarked for domestic consumption. The earmarked barrels of crude oil return first as petrol, then, in terms of monetary flow, as Naira, not dollars. This is because the resultant petrol from DCA is paid for in Naira, not dollars. It is worth highlighting that there is no guarantee that the Naira payment from DCA would translate to commensurate, or even any, revenue to the Federation Account. This is because the national oil company has always been in the habit of making upfront deductions for sundry reasons from revenue accruing from the DCA. The DCA is the site where NNPC performs its dark magic.

Crucially, the DCA policy not only provides an insight into why the national oil company failed to make remittances to the Federation Account for a long spell but also explains why forex inflows from sales of Federation’s crude oil dwindled and the country’s external reserves stagnated at a period of historically high oil prices.

Countries with low forex supply against demand can adopt a number of measures to increase foreign exchange inflows. Such measures include external loans, deposits by deep-pocket investors and countries, foreign direct investment (FDI) and foreign portfolio investment (FPI) and increasing other sources of exports (non-oil exports in Nigeria’s case). However, loans are likely to be one-off and have to be repaid and with interests (even if concessional). Investors are known to take their time and they can be fickle. Unlocking other sources of exports requires time too.

While the country needs to pursue all these options as both stop-gap and long-term measures, it should urgently embrace the one option that is largely under its control and can ensure a steady and sustainable flow of foreign exchange: earning dollars from the sale of its crude oil wherever it is sold. For this to be possible, the DCA policy needs to go immediately. Cancelling the DCA is the easiest and most predictable way to boost forex flows into Nigeria and the most realistic way to reduce pressure on and provide relief for the Naira.

DCA as the Missing Part of the Forex Puzzle

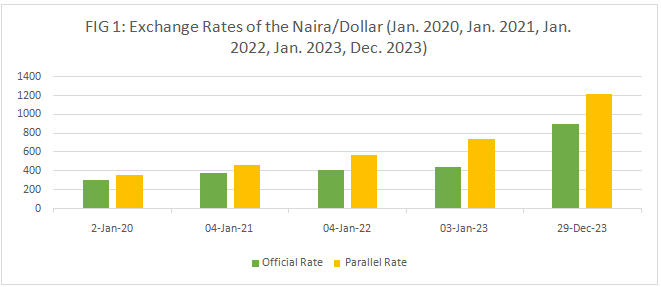

On23 September 2023, the exchange rate of the Naira to the U.S. dollar on the parallel market reached N1,004/$1, thus crossing the N1000/$ psychological mark1. This marked a significant milestone in the foreign exchange markets in Nigeria. The exchange rate of the Naira has been under pressure for some years, andit has been particularly unstable in the past three years. On 2 January 2020, the Naira exchanged for the dollar at N306.5/$ and N360.5/$at the official and parallel markets respectively (Figure 1).On 29 December 2023, the exchange rates of the Naira to the dollar jumped toN899.9/$ (official) and N1,215/$ (parallel) (Figure 1). Compared to the 2 January 2020 rates, this represents a depreciation of 66% for the official rate and 70% for the parallel rate.

Sources: Central Bank of Nigeria; Analysts Data Services and Resources

While many analysts and commentators have provided different explanations (including conspiracy theories) about factors responsible for the depreciation of the Naira, the primary cause is the simple economics law of demand and supply: the supply of foreign exchange in the country has not been sufficient to meet the demand. The country has a backlog of foreign exchange obligations estimated at between $4 billion and $7 billion by the new Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN)during his Senate confirmation screening2,3. The backlog has been occasioned because there was simply not enough foreign currency in the country to meet demand. While the restrictive policies of the CBN had been able to suppress the effects of the pent-up demand on the exchange rate, the recent liberalisation has shown the full extent of the excess demand.

Following the removal of foreign exchange controls on 14 June 20234, the Naira was effectively floated, and the workings of market forces saw an immediate depreciation of 29% at the Investors and Exporters (I & E) window, with the exchange rate moving from N471.67/$1 to N664.04/$1. Further liberalisation came on 12 October 2023 with the removal of foreign exchange restrictions on imports of 43 items5.While the removal of these foreign currency restrictions has on one hand limited subsidisation in the foreign exchange markets, on the other hand, it has resulted in increased prices for imported goods (including petrol), and higher costs for foreign transactions (such as school fees and medical costs). This, coupled with seemingly constantly rising prices, has meant that the exchange rate of the Naira has been a dominant topic of discussion in the polity for the past six months.

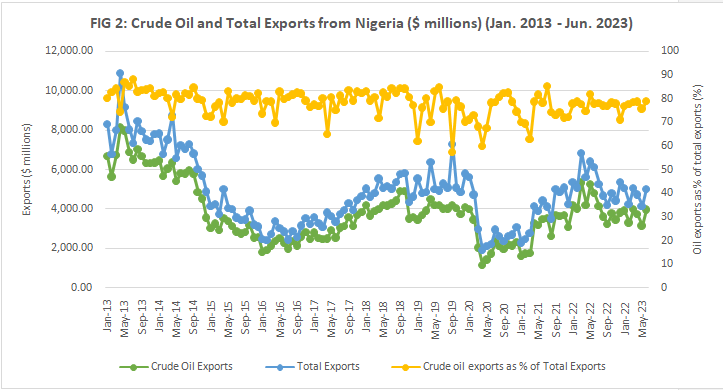

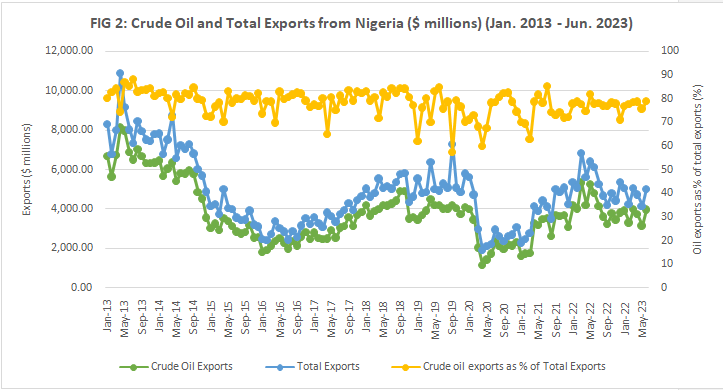

Despite the reforms, a lingering issue for Nigeria and the value of the Naira is that the supply of forex continues to track below demand. At the heart of the reduced supply of foreign exchange is the decline in USD inflows into Nigeria’s external reserves arising from lower oil receipts. A key explanation for this is the drastic reduction in oil production, and consequently oil exports. Oil exports have typically accounted for over 70% of total exports (Figure 2), and have, since the commencement of commercial oil exploration, provided the bulk of foreign exchange earnings for the country. However, oil production started falling drastically in the second half of 2020, and remained largely below 1.4 million barrels per day (Figure 3). Production dropped further in 2022 and was below one million barrels per day in August and September. Although it subsequently increased, production has not risen above 1.4 million barrels per day since then. The country has not been able to meet up with OPEC production allocations since July 2020 (Figure 3). Between March 2022 and August 2023, the shortfalls were so acute that they were above 450,000 barrels per day.

Source: Central Bank of Nigeria Quarterly Statistical Bulletin, 2023 Q2

Notes: 1. Crude oil exports as % of Total Exports are measured in percentages on the right-hand vertical axis

2. Crude oil exports and Total Exports are measured in millions of dollars on left-hand vertical axis

Sources: Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission and OPEC Statistical Bulletin

Though a lot of attention has rightly focused on declining oil production with government officials and the media putting the blame on oil theft, this is only a part of the story as oil prices after declining over the 2014-16 period and during the COVID-19 pandemic have been broadly supportive of oil export receipts. Ordinarily, the decline in oil production should have been compensated for by significant rise in oil prices following the war in Ukraine. However, there has been a secular decline in the ratio of oil inflows into Nigeria’s external reserves and oil export receipts. We posit in this paper that the reduced forex flows reflect increased allocation of Federation’s crude to DCA at the expense of direct Federation oil exports which normally translated to dollar flows.

DCA involves ‘domestic’6 sales of crude oil, thereby bringing revenues in Naira, the domestic currency. Depending on the terms of the different production arrangements, crude oil produced in Nigeria is shared between the oil companies and the Federation. NNPC is responsible for selling the Federation’s share of the total oil produced. NNPC in turn allocates the Federation share either for exports or for domestic utilisation7. It is the component for domestic utilisation that is referred to as domestic crude allocation (DCA). The critical point to note is that the different allocations are paid for in different currencies: revenue from Federation exports is received in dollars and revenue from DCA is received in Naira.

With the dwindling oil production, a larger proportion of the Federation’s quota has increasingly been channelled to DCA. This has led to the situation where most of the oil revenue inflows have been in Naira, as opposed to dollars. It is our considered position that switching crude oil allocations from the DCA to exports will provide steady revenue in foreign exchange, and thus boost foreign exchange supply in Nigeria. Ultimately, an increased and steady supply of foreign exchange will ease demand pressures and help to stabilise the Naira.

Good Intention Gone Sour

The current outsized role of the DCA started around 2005 with the arrangement that about 445,000 barrels of crude oil per day (the nameplate capacity of the Nigeria’s four government-owned refineries) be set aside from Federation’s share of oil, and be channelled for domestic refining through sales to the then Pipelines and Product Marketing Company Ltd. (PPMC).The allocation would be paid for in Naira and PPMC would recoup proceeds via distribution and sale of the resulting refined products within Nigeria. The rationale was that such exclusive domestic allocation of crude oil would guarantee energy security, de-link refined petroleum product prices from volatility in exchange rates and international crude oil prices, and ensure adequate supplies of refined petroleum products in the country.

On the surface, the DCA seemed to be a reasonable idea, and a number of benefits of such an arrangement can be easily gleaned. It would help to insulate the country from price volatilities in the global oil markets. Such volatilities would be manifested in higher or unstable prices of petroleum products, scarcity of petroleum products, and uncertainty or unstable supply of petroleum products. Effectively, domestic crude allocation would ensure that Nigerians reap considerable benefits from being citizens of a major oil-producing

country. However, the policy had one notable weakness: a flawed pricing framework. On the one hand, the crude from the DCA was sold to the PPMC at an implied discount in dollar terms, when adjusted for the exchange rate, in comparison to the international market. On the other hand, the Naira sales price for refined products was delinked from Naira cost price to PPMC implying a subsidy whose bill was to be covered in annual budgetary allocations. In essence, the DCA created two layers of potential losses: first to the Federation in terms of potential export revenues and second to external reserves in the form of forex inflows. In addition, in de-linking domestic petrol prices from the underlying cost drives of refined petroleum products, the DCA pretty much created an incentive for the expansion of Nigeria’s petrol subsidy programme. The failure to incorporate the opportunity cost concept in economics would have dire implications further down the line for fiscal revenues and dollar proceeds while creating perverse incentives for malfeasance.

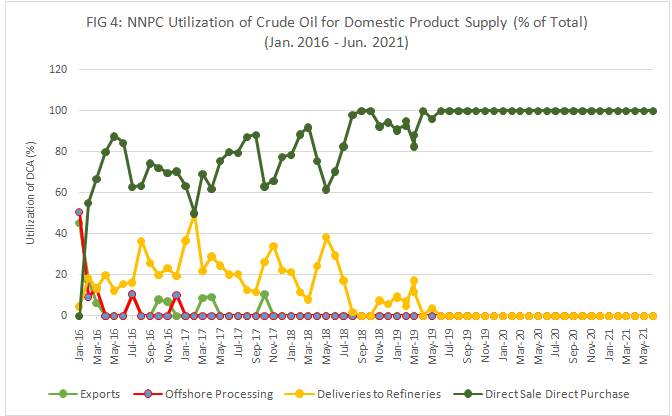

In what follows, we highlight some of the critical problems of the DCA8.Firstly, the losses borne by the PPMC provided little legroom to make the required investments in Nigeria’s domestic refineries which gradually fell into disrepair. Nigeria’s domestic refining capacity fell to low digits with zero allocation to the refineries from the DCA in 2020. While the loss in domestic refining capacity should have resulted in a termination of the DCA policy, successive Nigerian governments, desirous of ensuring low domestic fuel prices, responded by using the DCA barrels to enter into different arrangements (such as swap, offshore processing arrangements and direct sale and direct purchase) with international refineries and commodity traders to basically barter crude for refined petroleum products.

For much of the earlier period, the actual DCA arrangements amounted to sacrificing an insignificant share of Nigeria’s oil production for refined petroleum products. Given relatively tepid international oil prices for the much of the 1990s and early 2000s, the arrangement was not burdensome from a fiscal and FX perspective. Importantly, DCA usage was below 10% of the total Federation share of oil. However, by 2005, the decision to allocate about 445,000 barrels per day to DCA bumped up significantly the share of the Federation oil allocated for domestic consumption.

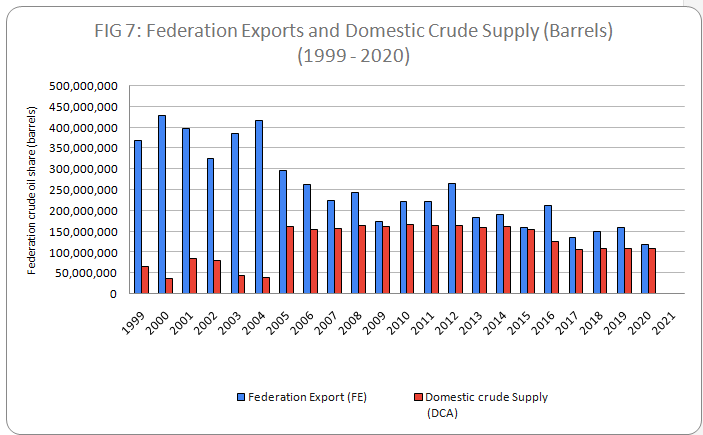

In 2004, for instance, only 39 million barrels or 8.57% of the 455 million barrels of the Federation share was allocated to domestic consumption, with the remaining 91.43% allocated to Federation exports. Following the policy mentioned earlier, the picture changed dramatically in 2005, with 160.9 million barrels or 35.25% of Federation’s share of 456 million barrels set aside for domestic consumption. The percentage devoted to DCA has steadily increased since then. In the early stages, NNPC refined some of the allocation locally, swapped some for refined products abroad, and exported the rest, which it paid for in dollars. Before long, things went downhill. The refineries basically collapsed, the crude for domestic consumption was all refined abroad or bartered, upfront deductions by NNPC from DCA increased, and the petrol subsidy programme soared.

Since 2016, DCA crude has been increasingly sold through the Direct-Sale Direct-Purchase (DSDP) arrangement (Figure 4). While the refineries no longer receive crude oil, the DSDP arrangement ensures that crude oil receipts are still in Naira, as opposed to dollars.

Sources: NNPC Monthly Financial and Operations Reports

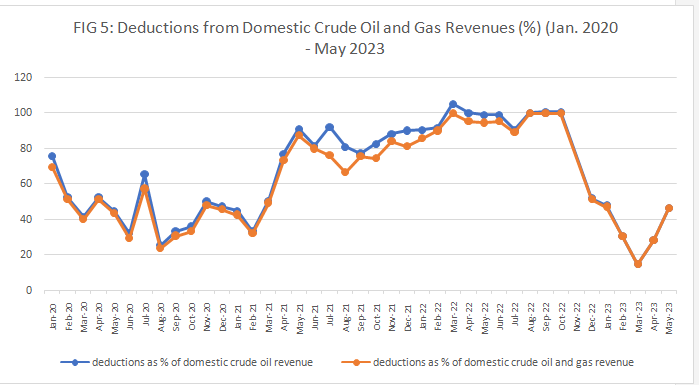

Second, the larger proportion of revenuefrom DCA was largely retained by the NNPC, meaning that the Federation progressively received less and less. Revenue from the DCA has been used by the NNPC for many years to finance its operations. Payments for subsidies, pipeline repairs and maintenance, product losses and lately JV cost recoveryare financed with DCA receipts. In January 2020, total deductions as a percentage of domestic crude oil revenue were 75% (Figure 5). This fell and reached 24% in August 2020. However, it started rising and reached 100% in March 2022. With the exception of July 2022 when it fell to 89%, it remained at 100% until October 2022.

This implies that all revenues from DCA were retained until October 2022, which also coincided with when NNPCL stopped making remittances to the Federation Account. The implementation of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) resulted in changes to the composition of deductions, leading to its percentage as a share of domestic crude oil and gas revenue falling to 15% in March 2023, before rising to 46% in May 2023 (see Box 1 for a more detailed description of deductions). Reporting of deductions ended in June 2023. The implementation of the PIA, coupled with removal of petrol subsidies, likely reduced the burden of deductions.

Sources: NNPC Presentations to the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) Meeting

Notes: 1. Between January 2020 and October 2022, total deductions consisted of JV Cost Recovery + Total Pipeline Repairs and Management Cost + Total Under-Recovery + Crude Oil & Products Losses + Value shortfall

2.The author was unable to obtain data for November 2022

3. Between December 2022 and May 2023, official deductions consisted of JV Cost Recovery + PSC(FEF) + PSC (Mgt Fee).

4, From June 2023, NNPC stopped reporting deductions as previously constituted.

5. See Box 1

| Box 1: Composition of Total deductions from DCA (January 2020 to November 2023 |

|---|

|

1) Between January 2020 and July 2022, total deductions consisted of three components: a. JV Cost Recovery (T1/T2)

b. Total Pipeline Repairs and Management Cost

i. strategic holding cost ii. pipeline management cost [January to April 2020, June 2020] iii. pipeline operations, repairs and management cost c. Total Under-Recovery + Crude Oil & Products Losses + Value shortfall

i. crude oil & product losses [reversal of product loss in May 2022 ii. PMS Under-recovery (Current + arrears) [January 2020 to April 2020] iii. Value loss due to deregulation [July 2020] iv. NNPC value shortfall (recovery on the importation of PMS/ arising from the difference between the landing cost and ex-coastal price of PMS) [March 2021 to October 2022] 2. For some months, the only deductions were for JV cost recovery [October 2020, January 2021, February 2021] 3. For August 2022, the only deductions were for NNPC value shortfall 4. From September 2022, there were changes in NNPC’s deductions, attributed to the PIA: a. Dollar deductions for NNPC value shortfall: 40% of PSC profit due to Federation (in addition to naira deductions: 100% of DCA revenue); b. No deductions for JV cost recovery and total pipeline repairs and management cost. Deductions for JV cost recovery resumed in December 2022; 5. From December 2022 (unclear if this change happened in November or December, as we were unable to obtain data for November), the composition of deductions changed and consisted of: a. JV cost recovery (naira and dollars) b. PSC Frontier Exploration Funds (FEF) (dollars, naira deductions started in February 2023) c. PSC (Management Fee) (dollars, naira deductions started in February 2023) 6 From December 2022, statutory payments to NUPRC (royalty) and FIRS (taxes) which had stopped in July 2021, commenced again (payments were made in September 2022) 7. From December 2022, payments started for NUIMS for profits 8. From February 2023, Payments for Federation PSC Profit Share in naira started (in addition to payments in dollars which started in December 2022) [40% of gross oil and gas revenue] 9. From December 2022 to May 2023, the addition of the official deductions (JV + PSC(FEF) + PSC (Mgt Fee), statutory payments (NUPRC + FIRS), NUIMS profits, and PSC profit share (from Feb 2023) are equal to DCA revenue. 10. From June 2023, NNPC stopped reporting deductions on the template. Rather, there was a section called Transfers, comprising 2 components: a. Transfer from PSC profits, comprising: i. PSC (FEF) ii. PSC (Mgt Fee) iii. Federation PSC profit share b. NNPC Ltd. calendarized Interim dividend to Federation Account c. The addition of the components under Transfer from PSC Profits was equal to total revenue from domestic crude oil and gas sales |

In recent years, Nigeria’s oil production (including condensates) has declined from the standard 2m barrels per day (mbpd) to a low of 1.1mbpd though this has recently stabilised around 1.4-1.6mbpd. As a result,crude oil production has not been able to meet budgetary targets or OPEC production allocation quotas as shown in charts above. This failure has been attributed to reflect a mixture of theft, outages from downtime during repairs and declines in underlying production as Nigerian oil fields mature in the face of reduced investments.

Since the 2010s, international oil majors have scaled back investment in Nigeria in the face of regulatory uncertainty following the delayed passage of the Petroleum Industry Bill, rising operating costs due to increased security and environmental clean-up, and growing pressures from climate change activists to cut emissions from oil projects with high greenhouse gas emissions. These factors have pushed oil majors to shift investments away from the high-cost onshore fields with less attractive fiscal terms to deep offshore projects with more favourable fiscal terms and greater stability. The preference for offshore assets has seen a wave of asset disposals of onshore fields to domestic producers who have struggled to increase production given their weaker access to global capital markets to raise financing for exploration and production.

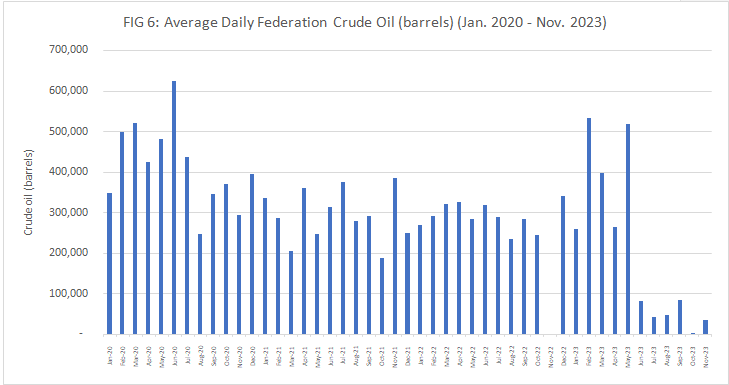

The derivative of the reduced oil production is that the Federation’s share of oil production has fallen dramatically. The daily average of the Federation’s share of crude oil was 414,463 barrels in 2020, 292,198 barrels in 2021, 290,649 barrels in 2022, and 205,184 barrels in 2023 (Figure 6). These are far below the daily average of one million barrels per day that accrued to the Federation between 2004 and 20149.Another important dynamic of import is that Nigeria’s oil production is now largely concentrated in Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs), where, by their design, oil companies get a larger share of production.

Sources: NNPC Presentations to the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) Meeting

Notes: 1. The author was unable to obtain data for November 2022

The net effect of the lower Federation share of crude oil is that domestic crude has assumed a larger portion of the Federation’s share of crude oil (Figure 7). As total Federation crude has fallen continuously in the past four years, an increasingly larger share has been allocated for domestic sales (Figure 8). Domestic crude allocation reached 99% of total Federation allocation in May 2021. Since then, it has not fallen below 95% (exceptions were in June 2021, March 2022, February - March 2023, June – August 2023, October 2023).

The dominance of domestic crude allocation has important implications for the foreign exchange market. Because sales of domestic crude are received in Naira, the fact that virtually all Federation sales of crude oil since May 2021 have been of domestic crude means that the bulk of crude oil revenue has been received (when it is received) in Naira, rather than in dollars. The fact that crude oil revenue is no longer being received in dollars has important negative implications for the supply of dollars in the economy, and the nation’s external reserves.

Sources: NEITI Oil and Gas Audit Reports

Sources: NNPC Presentations to the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) Meeting

Notes: 1. The author was unable to obtain data for November 2022

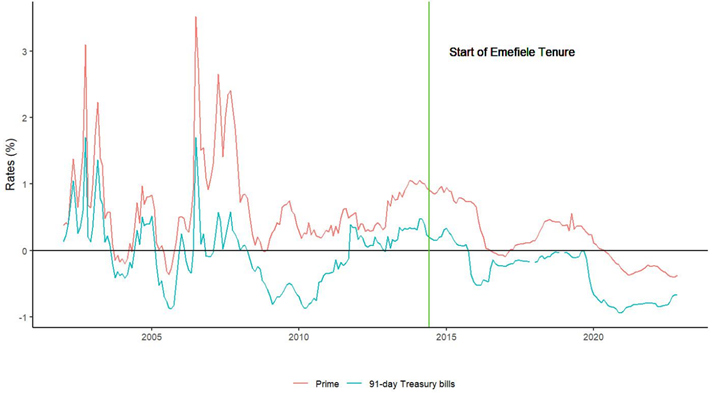

The oil and gas sector has traditionally accounted for the largest part of foreign exchange inflows to the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) (Figure 9). In 2010, foreign exchange inflows through the oil sector accounted for 94% of total inflows through the CBN. However, this started falling and had dropped to 24% in June 2022 (January to June).Foreign exchange inflows through the oil sector which were above 80% between 2010 and 2014, fell and remained below30% from 2017 to 2022 (Figure 9).

Source: CBN Quarterly Statistical Bulletin, volume 11, no. 2, June 2022

Notes: 1. The data ends in June 2022, because the CBN no longer provides disaggregated data on foreign exchange inflows

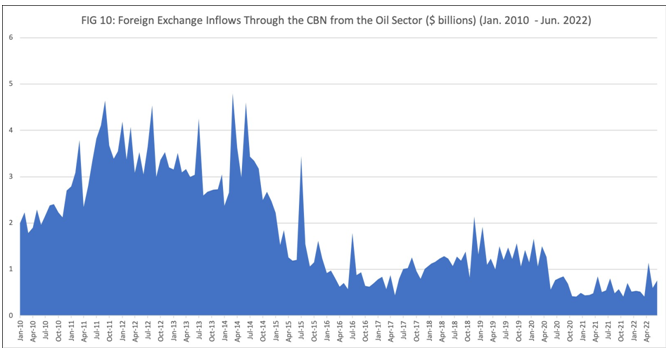

In January 2010, the oil sector brought in $1.99 billion through the CBN. This increased and reached $4.79 billion in March 2014 (Figure 10). Following this, it started falling and dropped to $922 million in January 2016. It rose and remained largely above $1 billion between July 2017 and April 2020. Then, it started falling and remained below $1 billion until June 2022 (with the exception of April 2022). Optically, the secular downtrend in oil inflows coincided with the start of the DSDP programme which used DCA crude allocation at a period of low oil prices. Following the recovery in prices over 2017 and in the 2021-2022 period, oil inflows have failed to recover mainly because most of Federation’s share of oil is being allocated for domestic consumption which does not translate to forex earnings. At an average price of $100/bbl and $84/bbl over 2022 and 2023, the nameplate DCA crude of 445kbpd would have translated into monthly inflows of $1billion to external reserves. However, as these sums were likely received in Naira, the opportunity cost is the reduced supply of FX by the CBN and the resulting demand pressures on the Naira.

Source: CBN Quarterly Statistical Bulletin, volume 11, no. 2, June 2022

Notes: 1. The data ends in June 2022, because the CBN no longer provides disaggregated data on foreign exchange inflows

While quick fixes cannot be implemented for returning steady foreign exchange inflows from oil to the levels experienced 10 years ago, ending the DCA and exporting the Federation’s share of crude oil can provide a steady supply of foreign exchange inflows. This would boost oil sector foreign exchange inflows through the CBN above the average of 24.2% experienced between 2017 and 2022. Assuming an average oil price of $70/bbl, the cessation of DCA could, before deductions, net $900million monthly which should bolster USD liquidity flows within the FX market. Critically, this will not be a temporary measure, but will be a steady supply of foreign exchange as long as crude oil is sold. Such steady supply will help in bringing some stability to the foreign exchange markets.

Fundamentally, with the removal of petrol subsidiesand the implementation of the PIA, there are virtually no more reasons for continuing with the DCA. Furthermore, the onset of the Dangote Refinery with a nameplate capacity of 650kbpd alongside recent announcements regarding a mechanical completion of repair work at the Port Harcourt Refinery (150-210kbpd) would imply a DCA that will further dim the prospects of forex from Federation’s share of oil if receipts are in Naira. Beyond legal realities, the DCA is impractical given the evolving dramatic changes in domestic refining capacity.

A caveat about the removal of petrol subsidies and implementation of the PIA is needed.

First, on subsidies, there have been reports that petrol subsidies are back in some form. The Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria (PENGASSAN) has stated that the government has restored subsidies10. The World Bank indicated the reemergence of an implicit petrol subsidy11.The Independent Petroleum Marketers Association of Nigeria (IPMAN) has also said subsidies have only been reduced, but not removed12. Careful consideration and strategic planning are needed on the issue of subsidies. The oft-touted palliative measures to alleviate the increase in cost of living of the hike in petrol prices have yet to fully materialise. This, perhaps, has been responsible for the reluctance of the government to allow the prices of petrol to fully reflect market prices. There needs to be a well-thought out and clear policy direction on the issue of petrol subsidies and the need to pursue full deregulation and extricate the country from the awkward and perverse incentives-ridden situation where NNPCL becomes the sole importer of petrol.

Second, on the PIA, recent guidelines by the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) have addressed the argument that local refineries need to be supplied with crude oil13. However, it is hoped that the new guidelines will stipulate that such domestic sales of Federation crude, if applicable, will be quoted in international prices and the payment will be made and received in foreign exchange. Failure to do this and properly manage and administer these new guidelines could present DCA version 2.0. Also, strict payment schedules must be stipulated and adhered to, so that there will be no backlog of payments. If properly administered, this new policy should not adversely affect foreign exchange inflows.

Conclusion

We have conducted an analysis of the rapid depreciation of the Naira in recent years. The central theme is that the supply of foreign exchange has not been able to meet up with its demand, leading to a backlog of foreign exchange obligations estimated at between $4 billion and $7 billion. With oil exports acting as a major enabler of foreign exchange inflows, the nation’s dwindling oil production was identified as an important contributor to lower supply of foreign exchange.

With lower oil production, higher proportions of the Federation’s share of crude oil have been allocated to domestic crude sales. Revenue from domestic sales is received in Naira, as opposed to dollars, thereby heightening scarcity of foreign exchange. We submit that the DCA has outlived its usefulness, and its continued use has proved costly to the country, especially for inflows of foreign exchange, thereby hurting the Naira. We recommend ending the DCA and selling Federation’s crude oil for exports, or if sold domestically to private refineries, to be sold in dollars. If this is done, steady inflows of foreign exchange will boost supply of foreign exchange, provide some quick wins to address foreign exchange scarcity, and help to maintain some level of stability for the Naira.

In October, the Federal Government announced plans for the injection of $10 billion of foreign exchange inflows14. These are expected to materialise from a variety of sources. Two executive orders were signed by the president in October: the first one will enable dollar-denominated instruments to be issued for purchase within the country; while the second is for issuance of dollar-denominated bonds for purchase by investors outside Nigeria15. Also, foreign exchange inflows are expected to receive a boost from the NNPCL through increased production, transactions such as forward sales, and investments from sovereign wealth funds16. In addition, NNPCL in August announced a $3 billion emergency crude oil repayment loan from the African Export Import Bank (Afrexim bank) “to support the Naira and stabilise the foreign exchange market”17.

Our central argument in this intervention is that while these measures can offer some succour and ease the pressure on the Naira, they do little to ensure a steady inflow of foreign exchange. They only provide emergency and temporary relief for foreign exchange stability.

In some instances, these measures have costs that, when fully considered, seem to outweigh the benefits. For example, the arrangement between NNPCL and Afrexim bank is a ‘pre-export finance facility’ (PxF) where the country has pledged 90,000 barrels per day for five years (2024 – 2028)18. This facility attracts an interest rate of 11.85%, which does not compare favourably with lower interest rates charged by international institutions for a longer period19. It is difficult to contextualise how the net effect of this facility will be of benefit, rather than loss to the country. It is more productive for NNPCL to concentrate on its core mandate and for the government to focus on how Nigeria can start earning foreign exchange again from the sale of the Federation’s share of oil. The DCA needs to go immediately.

*Professor Fowowe is an energy economist.

** Wale Thompson and Ifetayo Idowu contributed to this paper.

Footnotes

[1]The rate rose to N1,099.05/$1 on 8 December 2023 at the I & E window, but dropped back below N1,000/$1

[2] https://punchng.com/cardoso-to-clear-dollar-debts-suspend-intervention-loans/

[3] https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/nigerias-central-bank-governor-cardoso-pledges-clear-7-billion-forex-backlog-2023-09-26/

[4] https://www.cbn.gov.ng/Out/2023/CCD/CBN%20Press%20Release%20%20FX%20Market%20121023.pdf

[5]In reality, for many years, the crude oil has neither been utilized nor sold domestically, hence, the term ‘domestic’ has become a contradiction.

[6]NEITI 2021 Oil and Gas Audit Report

[7] Sayne, A., Gillies, A. and Katsouris, C. (2015) Inside NNPC Oil Sales: A Case for Reform in Nigeria, Natural Resource Governance Institute.

[8]https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/631482-nigerian-govt-still-pays-subsidy-on-petrol-pengassan.html

[9]https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099121223114542074/pdf/P5029890fb199e0180a1730ee81c4687c3d.pdf

[10]https://punchng.com/nnpcl-marketers-clash-over-subsidy-operators-peg-petrol-at-n1200-litre/

[11]https://www.nuprc.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/DOMESTIC-CRUDE-SUPPLY-OBLIGATIONS.pdf

[12]https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/636428-nigeria-expects-10-billion-forex-inflows-in-weeks-minister.html

[13]https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/nigeria-plans-new-fx-rules-in-hopes-of-naira-reaching-fair-price-by-end-of-2023-1.1991306#:~:text=Nigeria%20expects%20to%20receive%20%2410,summit%20in%20Abuja%20last%20week.

[14https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/636428-nigeria-expects-10-billion-forex-inflows-in-weeks-minister.html

[15]https://www.thecable.ng/report-afreximbank-approaches-oil-traders-to-finance-3bn-loan-to-nnpc

[16]https://www.thecable.ng/exclusive-nigeria-to-pay-11-85-interest-on-3-3bn-afriexim-nnpc-loan-pledges-164m-barrels-as-security#google_vignette

[17]Ibid.

- Details

- Policy Memo

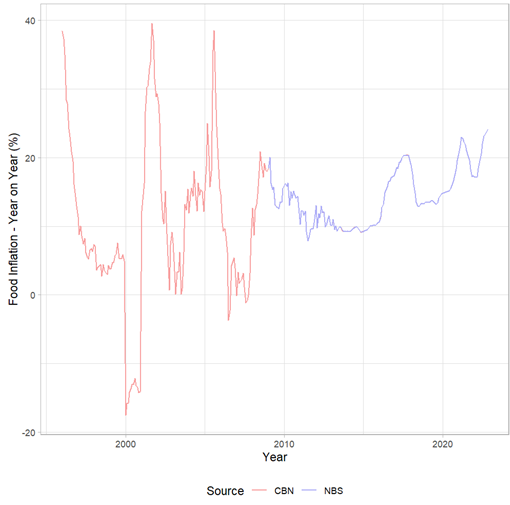

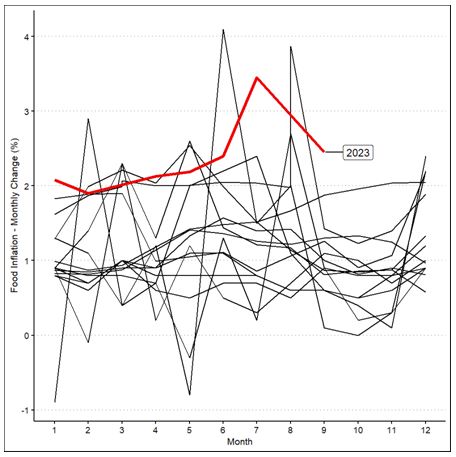

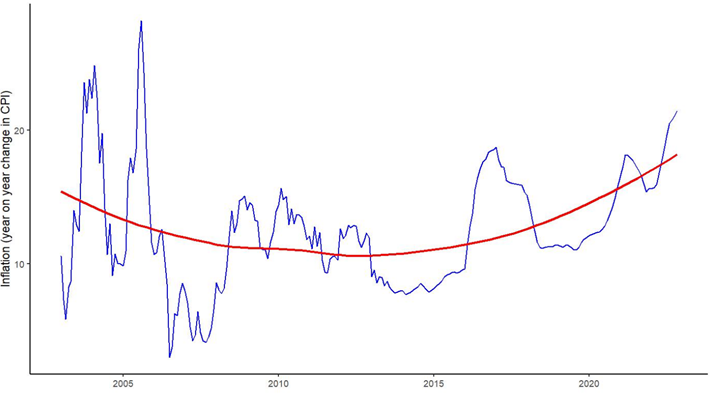

By Adebayo Ahmed | There is hunger in the land and you don’t need to go too far to see it. On almost every lip in the country today is a statement on how food prices are rising so fast that it is becoming increasingly difficult to survive. The data backs up this claim. According to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), food inflation, at 30.64% in September 2023, is higher than is has ever been since the NBS started reporting more formally on it in 2009. According data from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), food inflation was never persistently so high in the last few decades as it is currently. This situation has worsened in 2023 where monthly changes have never been so consistently high, at least since 2009. As is clear in Figure 2, this trend was present even before the removal of fuel subsidies which added to the pressure.

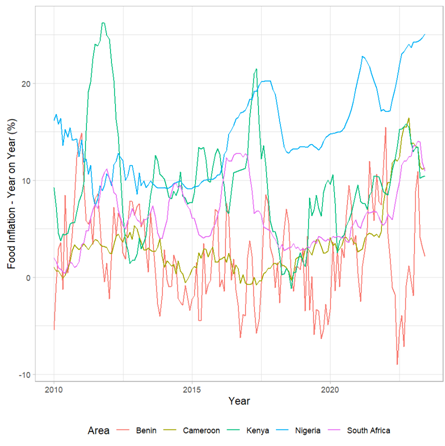

Fig 1: Food inflation chart. Source: National Bureau of Statistics. Central Bank of Nigeria.

The consequences for Nigerians and Nigeria are dire. Substantial segments of the population are struggling to feed themselves and their families, a situation which poses a threat to social and political stability in the country and worsens the country’s food insecurity profile. Though official figures are hard to come by, food insecurity has been on a steady increase in Nigeria for most of the last decade.

Fig 2: Monthly Change in Food Prices since 2009. Source: National Bureau of Statistics.

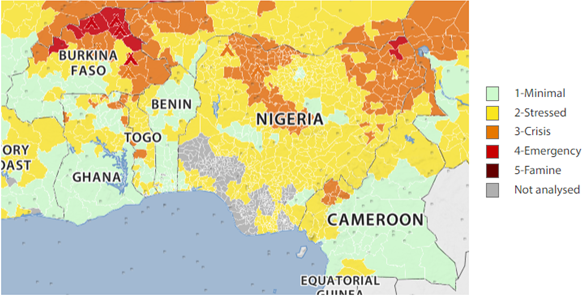

According to a recent publication by the IMF, more than 40% of Nigerians as at 2019 could be described as food insecure based on the average income and the amount of money required to consume the recommended number of calories1. This was before the COVID-19 pandemic and the following years of high food inflation. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that 69.7% of the people in Nigeria were moderately or severely food insecure as at 20192. The Cadre Harmonisie, a unified and consensual tool that measures acute food and nutrition insecurity in the Sahel and West African region, estimated that at least 25 million people in 27 states of Nigeria were at risk of facing hunger in 2023. The other nine states were not analysed so the overall number is likely higher.

Whichever way you slice it, there is hunger in Nigeria. It appears to be getting worse, and people are struggling to cope. Layering consistent spike in food prices with lingering and widespread food insecurity does not bode well for Nigeria. This combination should keep policy and development experts and officials awake at night, as there is something smoldering beneath the surface that could, with a mere spark, compound Nigeria’s unflattering development challenges.

Fig 3 Graph of index of nominal GDP per capita versus food inflation. Source: National Bureau of Statistics.

Importantly, this struggle is not just for people employed in agriculture. According to the 2023 Cadre Harmonise, the state with the largest number of people at risk of food insecurity is actually Lagos, where very few people are engaged in agriculture. Yes, there are apparently more people at risk of food insecurity in 2023 in Lagos that in Borno or Katsina or any of the agriculture-heavy states plagued by violence which disrupts food production and distribution. The reality is that food prices have likely been rising faster than incomes, squeezing households in the process. Although data on this is few and far between, a comparison of average growth in nominal per capita GDP and food inflation, as shown in Figure 3, makes this very clear. This does not mean that even those engaged in agriculture are also not feeling the pressure. As is clear in Figure 4, the hunger is spread almost across the entire country. Ironically, our neighbours, especially those who are not mired in some conflict are mostly fine, even if they are not significantly richer than Nigeria.

Figure 4: Food insecurity across West Africa. Source: Cadre Harmonisie.

Drivers of Food Inflation

What has caused this consistent spike in food inflation? We can think of this from a standard supply and demand framework. Things that disrupt supply tend to push prices up while factors that boost demand also tend to push prices up, and vice versa. Importantly, these factors in principle need to be “new” factors for them to matter, especially on the supply side. For example, if we have always had logistical challenges that hinder food distribution resulting in a mark-up on food prices then that does not really impact food inflation because it has always been there. However, if it gets better or worse, then it impacts food inflation for the better or worse.

The same can be said for our low levels of productivity, which are recognized as low even compared to our peers. For example, maize yields in Nigeria, at about 21,000 grams per hectare are lower than Ghana’s and even the African average, half as much as South Africa’s and Brazil’s and only a tenth of the United States’3. Low yields are bad especially for those employed in agriculture whose low yields imply they remain in poverty. But Nigeria has always had low yields and previously did not have such high food inflation.

What then, on the domestic supply-side could have worsened significantly enough to really impact food inflation? The escalation in violence, especially in key agriculture-intensive states in the North West and North Central is likely one culprit. The floods in 2022 which occurred during the peak harvest season also likely resulted in harvest losses and affected food supply. The COVID-19 pandemic and the disruptions to the fertilizer market as well as the markets for other inputs also likely negatively impacted food supply, at least for 2023.

However, in many countries the direct impacts of domestic supply shocks on food prices are actually pretty limited. This is because domestic shocks are mostly localised and don’t affect all food production everywhere. A drought might reduce production of maize in Zimbabwe but as long as the drought is not global, maize will be produced somewhere else and be traded in other places. International supply is vulnerable to shocks of course, such as is the case with the Russia and Ukraine crisis. Regardless, in the presence of international trade, the ability for domestic shocks to severely impact food prices should be limited.

Fig 5: Food inflation in select African countries. Source: Food and Agriculture Organisation – FAOStat.

In the last few years, global food prices have increased due to a variety of factors. That increase has however not been enough to explain most of Nigeria’s food inflation. As is clear in Figure 5, except those who are involved in some conflict, and whose livelihoods would be directly affected, food inflation is significantly lower in other African countries, and there is little food insecurity even in the face of similar global food shocks.

Indeed, it is more likely that Nigeria’s increasing restrictions to international food trade have contributed more to domestic food inflation. The anti-trade policies such as the border closure and the banning of foreign exchange for some food products have restricted international supply of food and put upward pressure on food prices. The exchange rate problem has probably also contributed to food inflation although it is likely not the major driver. A look at food inflation in Figure 1 shows two distinct patterns. The long-term trend which keeps inching upwards, and the more temporary bumps which can be attributed to the episodes of foreign exchange crises. The bumps are important of course but they are usually temporary. The longer-term upward should be of more concern.

The Role of Demand Pressures

What explains the more longer-term trend? On the other side of the price equation is demand. As basic economics suggests, prices can go up because of supply or demand. On the demand side we have a population that is growing by about 2.6% a year on average. This means actual food supply has to be growing by at least 2.6% in real terms just to keep up with population growth. In the presence of international food trade this will likely not be a challenge. But given that we have moved to limit food trade, then it becomes important. Unfortunately, in the past half a decade agriculture growth has slowed. In the 2nd quarter of 2023 agriculture GDP had slowed to 1.5% in real terms. It was negative in the first quarter. This means the agricultural sector wasn’t even growing fast enough to meet the demand pressures from a larger population.

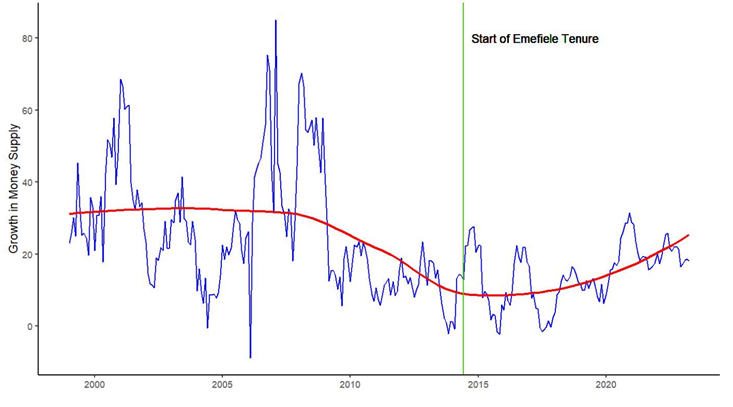

Fig 6 Select Food price inflation with Maize, Rice, and Yams highlighted. Source: National Bureau of Statistics

But perhaps a larger source of demand has been the growth in money supply. More money chasing fewer goods, including food, typically means higher inflation. Money supply has been growing at over 20% a year in the past few years4. This has likely contributed to the growth of inflation. In general, if you observe an increase in prices of a few goods then you can typically pin it down to supply side shocks. However, if you observe an increase in the price of all goods then it is likely a demand problem. As is clear from Figure 6, all food prices have been on the increase, including those produced locally and imported and those eaten by a few and those eating by many. In such a situation, the likely driver is too much demand driven by money supply that is growing too fast.

The Path Forward for Reducing Food Inflation

Given the likely causes of high food inflation identified above, the path to reducing it is clear. Simply, it involves tackling the challenges on both the demand and supply sides. Some things will be easier to implement and will result in quicker impacts while others will be more long term.

On the quick demand side, the obvious policy measure is to slow the growth of money supply. Regardless of what happens to the supply side, if money supply growth continues to be too fast then inflation, and food inflation, will continue trending upwards as well. If people’s incomes cannot keep up, then that additional means more affordability problems and even worse food insecurity.

On the quick supply side, the obvious policy measure is to ease the restrictions on international food supply. The borders may now be open and the restrictions on foreign exchange access for food and fertilizer may have been removed but there are still other significant restrictions, chief of which is the relatively high tariffs on food imports. The argument may be that reducing tariffs on food will negatively affect local producers of the food items. But there is a case to be made for the consumers as well. Consumer surplus matters and in principle more people eat food than grow food hence the consumer should matter at least as much as the producers. The best practice is not necessarily to have high tariffs on food but to re-channel some of the revenue from the lower tariffs to directly support food producers.

The more longer-term supply-side actions will include fixing some of the more structural issues that affect food supply: resolving the violence and issues in rural areas; resolving logistical challenges in food transportation; improving the productivity of farmers; building resilience to climate change; and so on. These are prescriptions that will be beneficial for food prices and food security in the long-term.

Right now though, quick wins are needed to halt the consistent price spikes that put food out of the reach of many citizens and potentially put the country at larger risks.

Footnotes

[1] Food Insecurity in Nigeria: Food Supply Matters. Thomas and Turk. IMF Selected Issues Paper No. 2023/018

[2] Food and Agriculture Organization - FAOStat

[3] Food and Agriculture Organization - FAOStat

[4] According to data from the Central Bank of Nigeria.

PHOTO CREDIT: Mansur Ibrahim

- Details

- Policy Memo

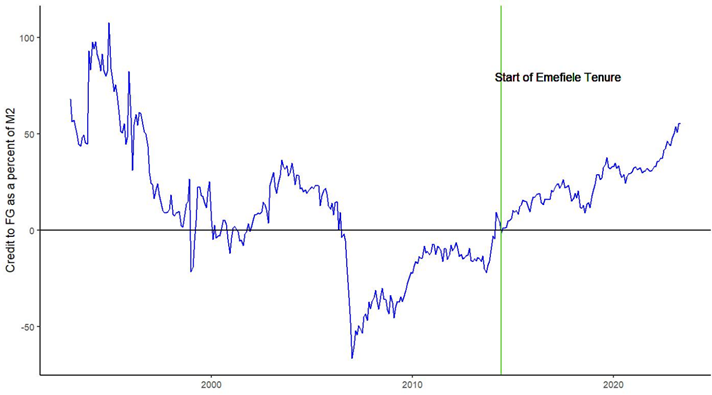

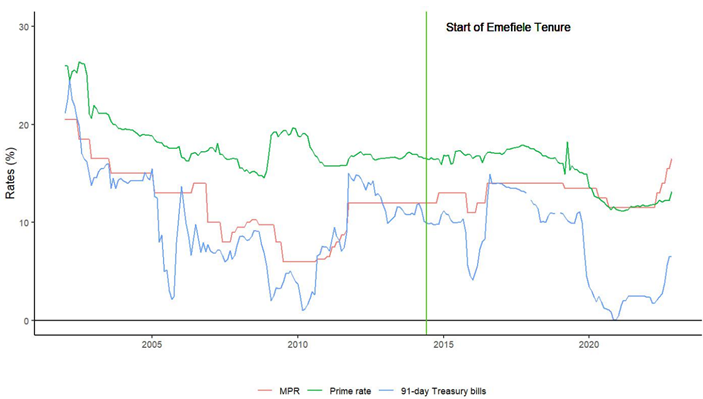

By Wale Thompson | In a surprise move on 14 June 2023, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) announced the removal of all restrictions on foreign exchange rates and signalled a willingness to tolerate greater flexibility in exchange rate determination as against the previous practice of a hard peg. In simple terms, the CBN ‘floated’ the Naira. This announcement was accompanied by directives which unified the multiple FX tiers invented by Mr. Godwin Emefiele, the suspended CBN governor, and specified the re-introduction of a “willing buyer, willing seller” arrangement for Nigerian foreign exchange markets.

This policy shift was consistent with the expressed desire of President Bola Tinubu for a unified exchange rate in his inauguration address of 29th May 2023, as well as the yearnings of private businesses, analysts and financial market investors, who had been frustrated at the arcane rules and lack of liquidity associated with the previous era. In its aftermath, the Naira has lost around 40% of its value within the official window to close at NGN770/$ on the first day of trading, a development that has elicited a mix of cautious optimism and pessimism. While praises have poured in from international financial organisations, business elites and financial market investors and western countries, the fledging reform has also attracted an avalanche of knocks from segments of the media, labour unions and a growing number of citizens struggling with continued depreciation of the Naira and its adverse inflationary effects.

After the initial optimism surrounding the unification of the Naira, with the disappearance of the gap between the official and parallel market exchange rates, sentiments have turned pessimistic as trading activity in the Investors & Exporters (IE) window has remained stagnant, and parallel market premiums have widened to 20% with the value gap at N170/$. Alongside a steady decline in gross external reserves to $33.9 billion, concerns have heightened about the outlook for the currency and its knock-on effect on domestic prices and citizen welfare. Granted that FX unification was not an end to itself, but rather a means towards restoring improved forex liquidity flows and restoring capital flows, the initial signs have not inspired confidence that a resolution to the lingering FX crisis is at hand.

Given the speed within which the Naira floatation was executed without any concrete arrangements on bolstering dollar supply, focus has shifted to this unresolved item given thin dollar liquidity within the official segment (daily trading has averaged $106 million versus $110 million prior to unification) amid signs of fresh weakness at the parallel market. Without direct attempts to stem the tide, the temptation to return to the old ways of managing things might look attractive which might blow away the current opportunity.

What further steps are required to stabilise the emerging situation over the near term and what concrete policy adjustments should follow for Nigeria to have a more sustainable approach to exchange rate management? In what follows, we briefly review the Naira float policy, provide some historical context to exchange rate regimes—highlighting the expected benefits and potential pitfalls of fixed and floating systems—and provide some recommendations on how Nigerian policymakers should look to approach FX management in the near and medium term.

Naira Floatation: Shock Therapy in the Face of Fundamental Deterioration

For the fifth time in Nigeria’s post-independence history (after similar moves 1986, 1995, 1999-2000, 2017), Nigeria’s policymakers have elected to abandon a hard nominal exchange rate peg (with the most recent one set at N461/$) in the face of depleting external reserves. Interestingly, the CBN announcement on the seismic shift in policy did not provide any justification for the decision nor an admission that the old peg arrangement had failed.

This would suggest it was not an innate desire or willingness to change but rather a loss of ability amid growing political pressure following the suspension of the CBN governor. Indeed, only as recent as May 2023, the CBN organised a conference where many participants (including the present top brass at the apex bank) ‘celebrated’ one of the many confusing policies (RT200) of the old FX regime which has now been scrapped. Thus, it is more likely that a shift in political leadership catalysed an opportunity for the CBN insiders to save face by quickly returning to fundamentals as the basis for FX rate management.

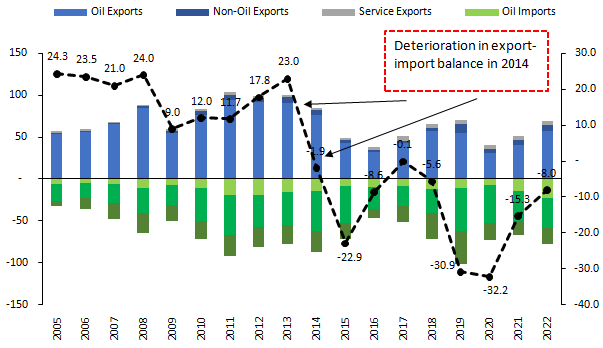

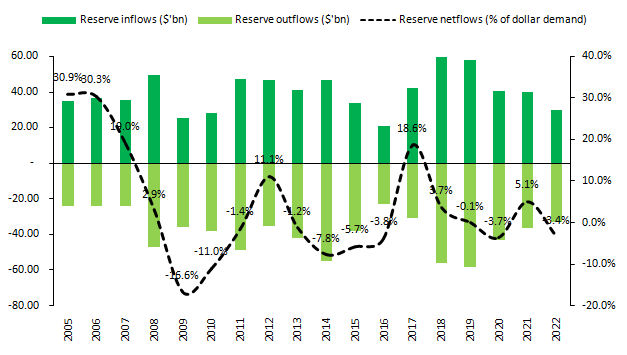

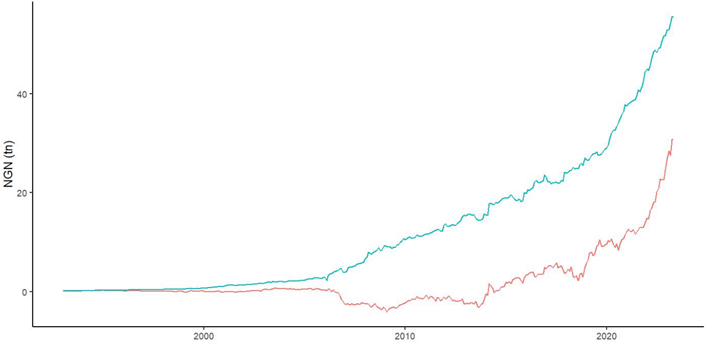

A look at the fundamental data reveals the existence of large imbalances in Nigeria’s external accounts occasioned by a mix of structural shifts and policy missteps by the CBN as the bane of the present FX woes. Between 2005-2013, Nigeria enjoyed a ‘structural surplus’ in the export and imports of goods and services (see Figure 1) primarily on account of higher oil export revenues due to stronger oil prices as oil production remained roughly static around2-2.2mbpd. This surplus exceeded $20 billion annually in the early part of the period (2004-2008) which allowed substantial external reserve accretion (peak $62 billion in September 2008) before moderating to $10-15 billion in 2010-2013 period.

Figure 1: Nigeria’s export import balance 2005-2022 (USD’billion)

Source: CBN

By design, the CBN has a fiat ownership of export petrodollars (a flaw at the heart of Nigeria’s FX architecture which we shall see later), which allows the apex bank to situate itself at the heart of FX management during boom times with the ability to determine to a large extent the price (exchange rate that most people get dollars) and quantities (USD allocation or who can get dollars). The latter being a derivative of the former as the readily available ‘stronger’ CBN rate ensured that its price set the tone for other FX segments. As a result, the official USD market was large enough relative to the non-official USD market so much so that the CBN began supplying dollars to retail end-users via Bureau-De-Change operators.

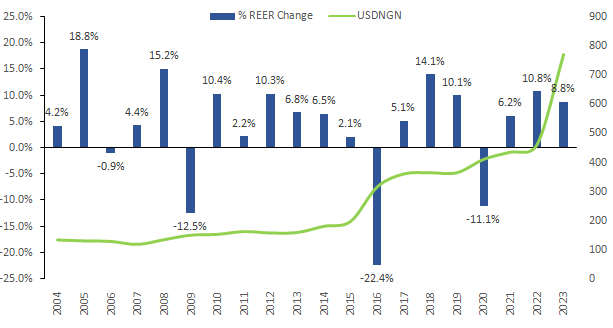

The large crude oil flows resulted in the adoption of a ‘defacto’ policy of exchange rate stability as the basis for monetary policy even though several CBN governors would publicly declare inflation targeting as the ‘dejure’ basis for monetary policy1. This commitment to nominal exchange rate stability also underpinned real exchange rate appreciation over the period. For context, while the nominal exchange rate weakened 16% (-1.8% per annum) over the 2005-2013 period, the Naira appreciated 55% (+6% per annum) in real terms which as we shall see had profound implications for non-oil exports and service imports.

Figure 2: Nominal USDNGN and annual change in the real effective exchange rate

Source: CBN, Bruegel *May 2023

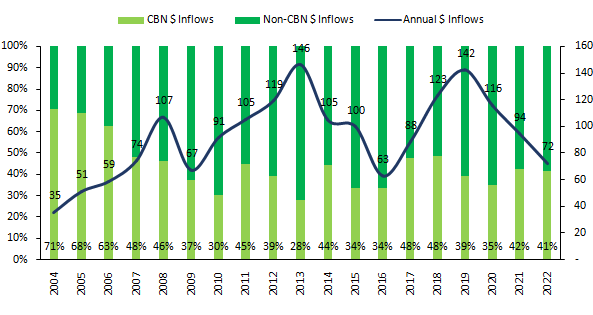

But first we turn our attention to dollar supply trends within the Nigerian economy. As noted earlier, at the height of the oil boom in the mid-2000s, the scale of the oil inflows and Nigeria’s shallow and less integrated financial markets (Nigeria had no bond market until 2007) implied that the CBN dominated the FX market accounting for between 60-70% of the total market. However, this dominance in terms of USD inflows declined to under the 50% in 2007 when CBN flows totalled $36 billion relative to non-CBN inflows of $38 billion implying that there was more USD coming into the Nigerian economy via autonomous sources than through the CBN channel.

This gap would widen in the coming years and at one point was more than double CBN inflows in 2010 ($63 billion vs $27 billion) before peaking at over $103 billion in 2013 (when CBN flows came to $41 billion). Essentially, the CBN dominance of the official market was an illusion helped by the commitment to exchange rate stability via a combination of tight Naira interest rates and relaxed FX controls. This allowed the CBN maintain the illusion of control that it determined prices within the official segments and could control the market.

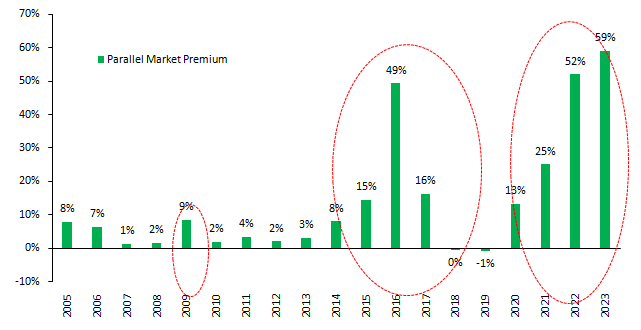

However, in 2009, despite fairly robust firepower with record reserves, the onset of the global financial crisis and the Nigerian banking crisis triggered a crisis of confidence in the Naira. This manifested in the form of widened spreads between the official and parallel market exchange rate which averaged 18% between March 2009 and June 2009 despite heavy CBN intervention so much that the apex bank briefly suspended the interbank FX market and eventually surrendered by devaluing the official peg to the level obtainable in the parallel market.

Though most literature have linked this divergence to the 2008-09 global financial crisis, in hindsight this was the first show of force by autonomous flows that CBN control of Naira determination was tenuous. It is within this context that we should interpret latter episodes of wider parallel market premiums (2014-17) and (2020-2023). In essence, given their size, autonomous flows would only equilibrate on CBN’s perception of Naira pricing when it was perceived to be ‘fair’ and not on CBN’s dictated terms.

Figure 3: USD Inflows to the Nigerian Economy

Source: CBN

Figure 4: Parallel Market Premiums

Source: CBN, Author’s Calculation *H1 2023

Nevertheless, CBN’s illusion of control allowed it to remain in charge of the official segment by offering a stronger exchange rate than the weaker rate available within the non-official segment, alongside the threat of sanctions, the CBN was able to finance over 60% of USD import demand between 2005-2013. Thus, to a large extent the CBN could dictate the FX rate that mattered for importers of goods and services and could supply liquidity within this segment.

However, the tectonic plates were shifting in Nigeria’s external accounts, a function of an artificially strong exchange rate. In particular, the share of non-tradables or services within the import basket had expanded greatly as Nigeria increasingly integrated into the global economy. Services share of imports rose to 30-40% levels from 20% driven by increased Nigerian consumption of foreign transportation (given the absence of a Nigerian flag carrier on international routes), education, health and financial assets.

The other big shift in dollar demand composition was in oil imports which rose from 10-15% in 2005 to 20-22% of total imports at end of 2022. In all, non-tradable service imports and oil imports, by-products of real exchange rate appreciation and an unrealistic fuel price subsidy regime would become the fatal flaws in Nigeria’s FX market architecture that would provide to be its Achilles heel.

But rather than directly address the unrealistic petrol subsidy regime or look to curb the growth in non-tradable service imports, Nigerian policymakers chose to periodically embark on import suppression on good imports which disproportionately target the poor. While the CBN would routinely institute FX bans on good imports, it would strive to provide FX for Nigerians looking to school abroad.

The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same…

Following the collapse of oil prices from an average of $100/barrel to under $50/barrel in the 2014-2017 era exacerbated by a drop in oil production in 2016, the fundamental situation changed. As in 2009, when the CBN held the line on the FX rate and suspended the interbank, the policy response was broadly similar in 2015: the apex bank froze the FX rate at N200/$, ended the Dutch auction system of weekly auctions and terminated the trading in the currency alongside liquidity restrictions within the official market.

As in 2009, the non-CBN flow market would respond by refusing to unite with the CBN dictated rate leading to an expansion in the gap between the official and parallel market exchange rates. Unlike the 2009 episode, the CBN however no longer had the fundamental picture of excess USD liquidity. But the CBN refused to recognise or accept the change in reality. In another replay of 2009, the apex bank resorted to tolerating excess Naira liquidity while imposing multiple restrictions, creating several FX layers and fighting an imaginary war on currency speculation.

It is important to highlight that the CBN actions was consistent with the expressed desires of former President Muhammadu Buhari even though the apex bank knew the truth of the underlying reality: that within the grand picture of FX flows, it no longer had the ability to underwrite a level of Naira exchange rate, especially after it had lost the faith of autonomous flows. While the CBN still held the line of regulating official transactions, this was an empty title: Naira’s rate determination would now take place away from official windows.

The difficult 2015-17 episode did have one major implication: unlike in the past when a desire for a stronger exchange rate overran the desire for USD liquidity, long taken for granted, the CBN response forced Nigerian corporates and citizens to realise that USD liquidity was of prime importance with pricing less so. Thus, began a game of chicken wherein the parallel market rate assumed prime importance while the CBN owned the title of master of no nation with its totemic official window.

It is against this backdrop that we should understand the present policy response: the adjustment to reality enforced by another cycle of deficits in the current account which authorities could not finance via reserve drawdowns or foreign portfolio inflows. The former is largely because the petrol subsidies financed via refined petrol for crude oil swaps curtailed inflows to external reserves while the latter is brought about by the pursuit of negative real interest rates and restrictions on FX access.

The second point bears some examination. As led by its now suspended governor, the CBN embarked on an experiment with unorthodox monetary policy which included large monetisation of fiscal deficits by ways and means, financial repression brought about by negative real rates, the imposition of a hard peg on the Naira exchange rate and direct balance sheet lending by the CBN to the real sector.

These unorthodox arrangements were initially sustained by a brief period of high oil prices in the external sector following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which helped mask weak oil production and the burdensome costs associated with a petrol subsidy regime. However, over the second half of 2022, the deterioration in oil production and out-of-control subsidy bill financed via crude-for-refined petrol swaps shrank inflows into the CBN’s reserves. As in Figure 5, declines in these flows tend to correspond with periods when Nigerian policymakers adjust their currency pegs to reality.

Figure 5: Reserve Inflows and Dollar Demand

Source: CBN, Author’s computation

A Brief History of Exchange Rate Systems

Flexible exchange rate regimes and their variants are now considered ideal for most economies, but this has not always been the case. Historically, the gold standard was the dominant exchange rate system, wherein currencies were equivalent to pre-defined weights of gold. This regime was in force till the end of World War II in 1945. Thereafter, countries shifted to pegging their currency values against the US Dollar as the dominant power while only the US Dollar maintained a fixed convertibility to gold.

However, as economies recovered from World War II and global trade expanded, along with significant growth in cross-border financial flows, pressure mounted on the US Dollar, leading the US Government to abandon the gold-USD convertibility in 1971. The inherent problem with fixed arrangements is that it required that countries with trade surpluses needed to strengthen their currencies, while those with trade deficits needed to weaken theirs, in order to achieve a balance in global trade which, in itself, is essentially a zero-sum game of winners and losers.

However, the pegged arrangement hindered this balance and countries with trade surpluses were reluctant to tolerate stronger currencies due to the effect on their export competitiveness. A similar explanation worked for losers in the global trade game as countries with trade deficits, often import-dependent economies were unwilling to tolerate widespread depreciation due to welfare implications. Thrown into the dynamic was the rise of financial assets which allowed investors to speculate on interest rates and currency adjustments, further intensifying pressure on the US Dollar and prompting the need for changes.

Numerous attempts to reform fixed exchange rate systems worldwide proved unsuccessful, prompting most countries to transition to some form of floating exchange rate system during the late 1980s and 1990s. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, more economies with pegged exchange rate regimes in the global south had to face this reality and experienced disorderly transitions from fixed to flexible exchange rate regimes. The dominance of the US Dollar in global trade between non-US countries, owing to its large liquidity and the non-convertibility of other major currencies, played a central role in this shift.

After the 1990s, countries adopted either fully flexible exchange rate regimes or some variant of flexibility, such as managed float. In the latter scenario, the level of central bank commitment to a peg determines the degree of flexibility in the exchange rate regime. The harder the commitment, the less flexible the regime, while a softer commitment results in a more flexible regime.

In Nigeria, from 1960 to 1985, the exchange rate was fixed at a 1-1 peg against the US Dollar in nominal terms, similar to much of the global economy. However, in real terms, the Naira became overvalued relative to the dollar following the collapse of oil prices in the early 1980s. Nigeria's over-reliance on a single commodity proved to be a major vulnerability for the wider economy during subsequent foreign exchange crises. Unfortunately, resistance from political and economic leaders to face reality created the perfect conditions for spectacular collapses once the ability (external reserves) to pretend about the exchange rate dissipated.

Flexible exchange rate regimes are preferable to fixed peg arrangements for several reasons. Firstly, flexible exchange rates provide an automatic framework for adjusting to external shocks and changes in economic conditions such as fluctuations in commodity prices or global economic downturns. A flexible system allows for countries to adjust their currencies in a manner that enables limited disruptions to trade and capital flows.

Secondly, flexible exchange rates grant more autonomy to monetary policy, enabling central banks to respond effectively to domestic economic challenges. In contrast, fixed peg arrangements can greatly constrain a country's ability to implement independent monetary policies, potentially exacerbating inflation as seen in Nigeria over the last eight years. Additionally, flexible exchange rates can foster competitiveness in export industries and prevent the build-up of unsustainable imbalances on the import side, supporting economic diversification and reducing reliance on a single commodity.

However, there are several variants of flexible exchange rate arrangements and there is no off-the-shelf variant for emerging markets like Nigeria. Rather, each country develops a commitment to ensuring that its exchange rate trends broadly mirror developments in the external accounts. To avoid the political golf ball that comes with currency adjustments wherein opposition politicians and others deploy exchange rate trends as part of political campaigns, there is need for transparency and clear communication around central bank’s actions and FX markets in general and commitment to a credible basis, usually inflation-targeting, for monetary policy.

Getting Nigeria’s Forex Reform on Track

Following several failed attempts at transitioning to a flexible exchange, Nigeria has embraced another attempt which needs to be situated within the context of wider discussions about macroeconomic strategy with the appropriate time frames. Mere FX adjustments to adapt to reality may lead to short-lived gains, followed by a return to previous practices. To avoid this cycle, forex and monetary policies should be part of a comprehensive economic plan where the exchange rate serves as a tool for export diversification and for attracting capital flows to foster overall development. Successful fixed to floating transitions are characterized by certain key features. Outlined below, these features should be taken on board by Nigeria’s policy makers in the medium to long terms:

- A clear role for exchange rates within the context of broader economic strategy: The exchange rate is a key input variable within the context of an economy: as it serves as a measure of relative prices between a country and its trading partners. The long-stated objective of Nigeria’s policymakers is to diversify its export base which given Nigeria’s labour abundance distils to ensuring that industrial activity is geared towards the production of exportable goods that use a lot of low-skilled labour that is abundant in Nigeria. To ensure export competitiveness of these non-oil exports, exchange rates policies must look to deliver an extra layer of competitiveness to export prices in a form that favours domestic industries. To this end, the goal of policymakers on FX is not nominal exchange rate stability but real exchange rate stability with an undervaluation bias. To this end, Nigeria’s FX policy must look to ensure a balance between real exchange rate stability that ensures non-oil export competitiveness and keeps inflation at a level supportive of domestic welfare. Nigeria’s economic managers must explicitly seek to achieve this balance and must demonstrate annually how their policy measures or adjustments deliver on these goals. The best example here is Singapore, where the central bank is required to publish annually how it goes about delivering balancing FX policy within the twin objectives of trade competitiveness and low inflation. Nigerian authorities must change the CBN Act with explicit references for the CBN to demonstrate how via its policy actions it ensures real exchange rate competitiveness and stable prices via reports published bi-annually.

- A deep and liquid FX markets: By definition, a laissez-faire market is one with many buyers and many sellers such that no one party is large enough to influence the actions of others. In creating a workable FX market architecture, Nigerian policymakers must envision a distinct set of supply forces i.e. multiple FX sources which can be attained by removing all forced sale rights on oil exports presently held by the CBN. Rather, the CBN should purchase its USD like every market participant to manage Naira liquidity at a level consistent with its own money supply objectives. Essentially, a credible FX reform will end the forced petro-dollar to Naira conversions financed via the printing of new money. The goal is to create an FX market with diverse players especially on the supply side: CBN, oil exporters, non-oil exporters, remittances, foreign portfolio investors etc.

- Consistent focus on price stability: In lieu of nominal exchange rate targeting, Nigeria’s central bank must have an explicit inflation targeting framework with clear annual and inter-mediate inflation target that are publicly known and must annually demonstrate how its policies achieve this objective. The CBN can have several inflation measures (consumer price index, producer price index, wage inflation etc) to prevent undue reliance on one metric and importantly it should demonstrate how its adjustment of policy instruments (interest rates and money supply) are enabling it move inflation within targets. Nigeria’s fiscal and legislative arms should be on hand to deploy censure to CBN governors unable to deliver within target inflation. To avoid the egregious abuses over the last five years, Nigeria should look to divorce CBN control over development finance banks and capitalise these entities to fund underserved sectors of the credit market.

- Curtailing information asymmetry through increased transparency and clear communication: To help proper FX pricing, Nigeria’s central bank must work to deliver increased information about demand and supply trends and end the dark ages on critical data on trends across FX markets. As in some markets like Singapore, the CBN legislation must include requirements for publication of period data and analysis of trends in FX markets to the public. This requirement must impose penalties for non-compliance. Under the suspended CBN governor, the CBN commenced data censorship with the withdrawal of more in-depth data which created no transparency on FX markets.

- Institutional mechanisms for hedging volatility: Beyond developing deep and liquid spot markets, concerted efforts must be on including avenues for hedging without any arcane restrictions that look to curb speculation. The CBN should work with exporters and financial institutions to develop the means for importers to hedge against FX volatility risk to prevent demand front-loading. Nigeria should work actively to ensure that the large USD flows (including remittance flows) equilibrate within the official segments.

- A clear framework for FX interventions: Market failure is a feature of still forming markets and Nigerian policymakers must be clear-eyed to have a system for dealing with periods when markets become volatile. Thus, there must be a clear operational framework for dealing with periods of external shocks which should include providing temporary US liquidity, interest rate adjustments, communication and FX adjustments.

Beyond these broad medium to long term objectives, policymakers must not ignore the near term. To stabilise the present spiral, Nigeria needs a big stash of dollars and fast! Policymakers must look to strike the iron while it is hot to avoid reform fatigue by seeking out sources of large USD liquidity on concessional terms by exploring the option of a standby arrangement from multilateral agencies of significant scale ($5-10billion) with the objective of acquiring credibility.

Having front-loaded fiscal consolidation and external sector adjustments, Nigeria has the credibility to embark on key partnerships to catalyse increased capital flows. While this is politically tricky, desperate times call for bold and desperate measures. The global geopolitical environment means Nigeria has a window to obtain this funding if it is ready to push the envelope. These dollar flows are necessary to give the market ‘time to breathe’ as left unsolved, the Naira could come under fresh speculative pressures which might drive a return in policymakers towards the very pegged arrangement they recently jettisoned.

The CBN must look to be flexible in thinking: there are several variants of flexible FX regimes and we should be pragmatic to not rule out any options. The goal is to ensure that FX adjustments reflect the trends in balance of payments in a credible manner over the near and medium term.

Footnote

[1] In its 2021 Article IV, the IMF noted that Nigeria’s monetary policy was inflation blind (see IMF Article IV 2021)

Photo Credit: Mansur Ibrahim/TheCable

- Details

- Policy Memo

By Bolaji Abdullahi | Section 4 of the National Policy on Education (in the 4th amended version) of 2004 states that the goals of primary education in Nigeria are to:

- inculcate permanent literacy and numeracy, and ability to communicate effectively…

- provide the child with basic tools for further educational advancement, including preparation for the trades and crafts of the locality1

In a nutshell, it is expected that at a specified age, every Nigerian child would have acquired the foundational cognitive skills that they could build on in a latter life of vocation or further learning. It is clearly recognised that without these foundational skills, the ability to read and write and perform basic mathematical functions, a human being cannot fully function as a productive political or economic citizen. Therefore, to deny a child the opportunity for basic education is to devalue the child’s citizenship and undermine the basis on which all future capabilities are built.

Apart from education being a part of the general constitutional right2, it is not surprising that the right to basic education is specifically guaranteed under the Child’s Rights Act (CRA), which states that:

“Every child has the right to free, compulsory, and universal basic education, and it shall be the duty of the government in Nigeria to provide such education3.

The Universal Basic Education (UBE) was launched in 1999. Its enabling Act, the UBE Act of 2004, reinforces the CRA and makes it a responsibility for every government in Nigeria to “provide free, compulsory, and universal basic education for every child of primary and junior secondary school age. More than two decades after the UBE was launched, it is important to examine the extent to which the programme has delivered on its key objectives of getting every child into school and equipping them with basic cognitive skills as stated by the national policy.

It would appear that some progress has been made in terms of enrollment as there are more children attending school today than at any other time in our history4. But we still have more children out of school than any other country in the world. Therefore, Nigeria’s enrollment figures, in or out school, may only be relative to its population size. In absolute terms, however, Nigeria has between 13 and 20 million children out of school5.

In terms of learning achievements, it has also been widely reported that Nigerian children are seriously falling behind. In its January 25, 2023 edition, The Guardian cited a UNICEF report that 75% of 14-year-old Nigerians cannot read a simple sentence or solve basic mathematical problems6. This confirms an earlier report in 2018 that only 20% percent of those completing primary school in

Nigeria can read7. Therefore, even when more kids are going to school, they have not been doing much of learning.

Indeed, the reality would suggest that Nigerians who are parents today got better education from public primary schools than their children are getting now, even twenty-four years after the UBE. In the past it could be taken for granted that any child completing basic education in Nigeria would have attained the appropriate levels of proficiency in reading, writing and arithmetic. Not anymore. Quite ironically, the chances that a child would acquire these competencies now lies outside the public schools and depend on the ability of the parents to pay.

Having lost faith in the public education system, parents who could afford to pay have opted out of UBEC-funded primary schools, leaving only those who are too poor to afford even the cheapest of fee-paying private schools or those who reside in places where such option is not available. The failure of children to learn from public schools, would, in fact, suggest that the more children we have attending those schools, the more children we have who are in danger of acquiring no education for a future life of further learning or employment. In only a few decades, Nigeria’s prosperity and progress will be determined by these children. Their inability to learn the skills to solve even the basic problems they will encounter clearly has serious implications for Nigeria’s social cohesion as well as future economic and human capital development objectives.

The issue of out-of-school children remains pertinent to any conversation about universal basic education. So much has been written about this in the past, and different factors have been identified as responsible for slow enrollment in different parts of the country or disparity in enrollments along gender lines within the same region of the country. However, the main focus of this paper is on improving the quality of basic education in the country.