Policy Platform

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Tayo Agunbiade | The results of the recently-held general election have once again confirmed the continued under-representation and marginalisation of women in politics and governance in Nigeria. Women constitute 49.3%of Nigeria’s total population, but only manage to secure 4.69% of the executive and legislative positions on offer at the federal and state levels in the elections held between February and March this year. The country’s highest law-making and decision-making bodies are thus guaranteed to remain excessively male-dominated for another four years. Deliberate policy and other steps must be taken to address this imbalance in the immediate and in the medium to long terms.

At the federal and state levels, Nigeria has a total of 1,534 electable positions. This is broken down as follows: two President and Vice President; 72 state governors and deputy governors; 469 federal legislators (made up of 109 senators and 360 members of the House of Representatives); and 991 members of the states’ Houses of Assembly. Out of these, women won only 72 positions in the 2023 general election. This amounts to a paltry 4.69% of the total executive and legislative positions on offer in the 7th electoral cycle in the 4th Republic, which commenced in 1999.

Of the 72 women elected in 2023, seven are deputy governors while the remaining 65 are federal and state legislators. On the bright side, there is a marginal increase over the performance of women in the 2019 electoral cycle when only 66 women were elected in all, with only four being deputy governors. This shows that overall female representation improved by 9.09% while the number of deputy governors increased by 75%. Also, there are some states, like Kwara, where female legislators in the state parliament shot up by 500%. However, these marginal gains are diluted by reversals at the federal parliament and maintenance of the gender status quo among the president, the vice president and state governors.

Great Expectations, Grim Results

There was an expectation that women would fare better in the 2023 electoral cycle. There has been a consistent increase in women’s interest and participation in Nigeria’s political and electoral fields. This awareness has also spilled over to civil society and over the years there has been high-level advocacy for more female representation in political and electoral leadership. So, what went wrong for the Nigeria’s female candidates?

For the presidential race, there was a drop in the number of female candidates seeking to occupy Aso Rock. This time around there was only one candidate namely: Ms Chichi Ojei of the Allied Peoples’ Movement (APM). This was a reduction from six women who featured on the ballot paper as presidential candidates in the 2019 election. The reason for this is due tothe fact that in 2019, there were 91 political parties, and many of them, unlike the older parties,welcomed women to contest in the presidential election on their platforms. To date, none of the older and main political parties have presented a woman candidate for the top posts of president and vice-president.

With the exception of Adamawa State, the male-centric culture adopted by most of the main parties on electable executive positions was replicated in the candidacy for the gubernatorial race. History was made in the state when for the first time a woman-Senator Aisha Dahiru, popularly known as Binani- was selected to run on the platform of aruling national party, the All Progressives Congress (APC).Indeed, it must be stated that this is the second time APC would select a woman as its gubernatorial candidatein North-East geo-political zone. In 2015, late Senator Aisha Jummai Al-Hassan was the party’s gubernatorial candidate in Taraba State.

There were also a handful of women as governorship candidates on the platforms of relatively smaller parties such as Binta Umar of the Action Alliance from Jigawa State; Hajiya Fatima Abubakar of the African Democratic Congress (ADC) in Borno State; Beatrice Itubor of the Labour Party (LP) in Rivers State; and Khadijah Iya Abdullahi of All Progressive Grand Alliance (APGA) in Niger State. This too is commendable. But regardless of this and by all standards, this electoral journey has proved to be a disappointment for women in Nigeria.

As is known, legislative institutions are at the heart of a democracy and globally there is vigorous consciousness about the importance of women’s agency and voices in law-making. Nigerian women are part of the groundswell of global advocacy for participation, representation and inclusion in national and state parliaments.

The number of women who contested for seats in the federal legislature was 380 (8.9%), out of a total of 4,223 candidates. A closer look at the breakdown of the candidates to the upper and lower chambers shows the following: Of the 1,101 candidates to the Senate, 92 were women; while there were 288 women of a total of 3,122 candidates for the House of Representatives. Only three of 92 women candidates won seats to the 109-seat Senate and 14 out of 288 to the 360-member House of Representatives. This means a total of 17 women will occupy seats in the 469-member National Assembly.

It is interesting to note that about 96% of the female contestants for the federal parliament did not win. This has been the trend. In 2019, 95.5 % of the contestants to the National Assembly suffered electoral losses, while in 2015, 94% of female candidates failed to win seats. This tells us the magnitude of defeat being experienced by women during the past few election cycles.

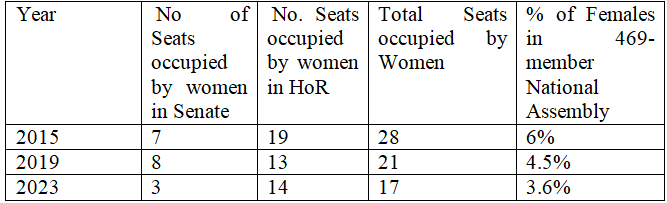

The critical issue at the other end of the spectrum is the drop in the number of seats occupied by women in the National Assembly. For the 10th National Assembly, female representation stands at 3.6%. In 2019, there were 21 women legislators (4.5%) and 28 (6%) in 2015. The data also points to the fact that women’s interests, voices and perspectives across the country will continue to be excluded and marginalised in the making of national legislation and the constitution review exercises.

One of the consequences of under-representation is the low success rate of women-related legislations. It will be recalled that the Gender and Equitable Opportunities Bill sponsored by Senator Biodun Olujimi is yet to pass through legislative hurdles since it was first presented in 2015. It was voted down based on reasons which include religion and culture as stated by some male legislators.

In 2021, Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha alongside 85 other legislators in the House of Representatives sponsored an amendment to the 1999 Constitution to create additional 111 seats which will be exclusively for women in the National Assembly. Although the bill passed its second reading, but overtime, it failed to garner the required support.

The most recent instance of how low representation negatively impacts women-related legislations occurred on 8thMarch 2022, when five Gender Bills which were drafted to amongst other things increase inclusion and representation of women in governance, were roundly rejected during the constitution alteration exercise. The bills address women’s rights, indigeneship, citizenship and affirmative action in appointments, as well as the executive committees of political parties and reserved seats for women in national and state assemblies. Yet there was a concerted effort on the part of several male lawmakers to see that none of these bills see the light of day. This was despite the fact that all 21 women legislators were members of the Constitution Review Committees set up by each chamber of the National Assembly.

Table 1 below shows the gender landscape of Nigeria’s federal legislature from 2015 to 2023 and highlights the extent of male domination of this national deliberative institution.

Table 1: Gender Landscape of 469-Seat National Assembly (2015-2023)

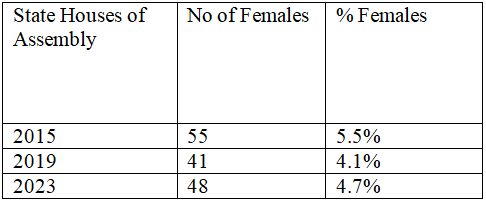

The outcome of the electoral race at the state level was no different.Of the 10, 231 contestants to the State Houses of Assembly, only 1,019 (9.9%) were women of which only 48 won seats to the 991-member State legislature. This indicates a success rate of a paltry 4.71% for female candidates at the state level. Besides the data revealing a 95.28% electoral loss at this level for women candidates, it also shows that there is only a negligible increase of seats in comparison with 2019. Women gained only seven seats more than the 41 won in 2019, to record a slight increment of 4.1 % to 4.7 %.

Table 2 below shows the gender landscape of Nigeria’s state legislature from 2015 to 2023 and also highlights the extent of male domination at the state level.

Table 2: Gender Landscape of 991 State Houses of Assembly (2015-2023)

As indicated in Table 2, the overall landscape in the state parliaments is similar to that which prevails at the national level, even though this legislature is generally regarded as being closer to the grassroots communities.

Mixed Results at State Level

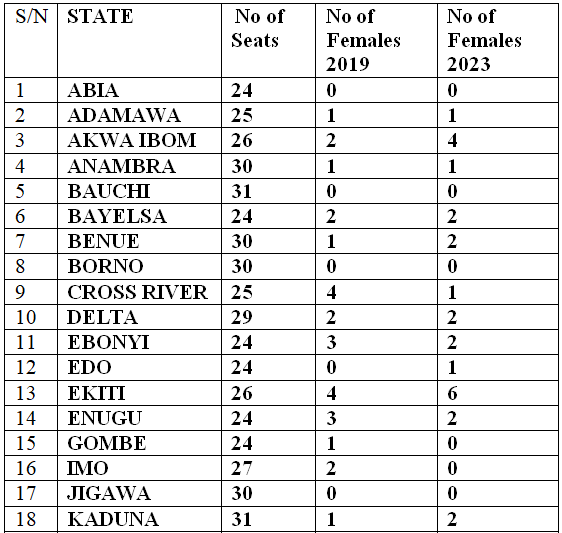

Notwithstanding the deepening gender gap in the legislative arm of government, some history has also been recorded at the sub-national level which must be hailed. For example, worthy of note is the fact that for the first time, the elections have produced a handful of women to the Houses of Assembly in the northern states of Kwara, Taraba and Kogi.

Indeed, Kwara State in North-Central Nigeria has for the first time recorded five women in its 24-seat Assembly. This is the second highest number of women, after Ekiti State in South-West Nigeria which has six out of 26 members. Against the backdrop of women’s share in the number of seats in past, these are milestones.

Marginal increases occurred in several states. For example, Ondo State went from one to three female lawmakers; Kaduna and Plateau both went from one to two; and Edo and Nasarawa went from zero to one each. Akwa Ibom went from two to four female lawmakers; while others like Bayelsa and Delta maintain their status quo of two female legislators each.

States such as Imo, Gombe, Niger and Rivers where previously there were a handful of female state legislators, are now left with none. Others like Cross River, Ebonyi, Enugu and Ogun saw a slight drop in their previous numbers. For example, Cross River went down from four women to one; Ebonyi from three to two women, and Ogun from four women to two.

Table 3 below provides the data of women in the State Houses of Assembly for 2019 and 2023.

Table 3: Female Representation in State Houses of Assembly (2019-2023)

Source: Dailytrust.com

Of the thirty-six states, fifteen states have no female representation in their Houses of Assembly for the in-coming legislative tenure. The states with zero female legislators in their houses of assembly are: Abia, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Imo, Jigawa, Kano, Kebbi, Katsina, Niger, Osun, Rivers, Sokoto, Yobe and Zamfara. In the out-going tenure of 2019-2023, a similar number of states do not have female representation. They are: Abia, Bauchi, Borno, Edo, Jigawa, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Sokoto, Taraba, Yobe and Zamfara.

Undoubtedly, there is a general decline in women’s electoral fortunes from the perspective of representation. The total number of women in both legislatures in 2019 and 2023 underscores this fact. In 2019 for the joint federal and state legislatures of 1,460 seats, there were 62 women (4.3%); while in 2023, only 65 women will sit in the federal and state legislatures (4.5%). Overall, this is a very marginal improvement in the number of women within public decision-making between 2019 and 2023. The marginal wins and heavy losses at the ballot box show that much more needs to be done to address the hurdles encountered by female politicians.

In terms of female parliamentarians, Nigeria lags on the continent. Rwanda has the highest proportion of seats held by women at 61.25%, which is also the highest figure in the world. In other parts of Africa, South Africa, Namibia and Uganda have 46%, 44% and 34% female parliamentarians respectively. In West Africa, Senegal has the highest number of women in its national parliament at 42.4% of the seats. Guinea and Mali have 29.63% and 26.45% respectively. Republic of Niger has 26%, Benin Republic, 25%, Togo, 18.7% Ghana, 14.5%, Sierra Leone, 12.33%, Cote d’Ivoire, 12.5%, Liberia, 10.96%, Gambia 8.6% and Burkina Faso has 6.3%. Nigeria, the largest country in the sub-region has the lowest number of women in parliament at 3.6%.

Some Reasons Why Women Lose at the Polls

To be sure, it is not the lack of participation per se that has caused the loss on such a scale by female contestants and left state institutions largely male dominated. There are other societal influences that hinder women from achieving the desired electoral results and over the years, there have been deep discussions about these factors.

Possibly the most pressing challenge to Nigeria’s electoral democracy is monetisation of politics and vote-buying. This is a recurring problem which has not been adequately addressed by the law. Among other provisions, sections85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 in the 2022 Electoral Act list: offences in relation to finances of a political party; period to be covered in annual statement; power to limit contributions to a political party; and limitations on election expenses of political parties etc. Butthe lack of enforcement continues to blight the political and electoral system.

Similarly, the Electoral Act does not have any provisions to address the lack of inclusion of women in political party hierarchies and candidates’ nomination and selection lists. Nigeria’s electoral laws must be strengthened to become more inclusive and INEC as the agency at the helm of electoral matters must through diligent enforcement, ensure total compliance.

Women politicians are also subjected to a variety of other factors which also includes bias in the media, god-fatherism, trado-cultural and religious barriers and so on. Similarly, election violence has seen loss of lives and destruction of property. For example, some women have lost their lives before, during and after elections. The reported cases of Emily Aborishade, Joyce Maimuna Katai, Salome Abuh and Emilia Gilbert from Ekiti, Nasarawa, Kogi and Rivers states respectively, and mor

e recently, Victoria Chintex in Kaduna State, come to mind. These killings must not be swept under the carpet, and perpetrators of all acts of violence must be held accountable. It is important to make the environment safe for all candidates, especially marginalised groups like women.

Historical Precedence and Patterns of Political Exclusion

Historically, women have been excluded and marginalised in electoral politics, public decision-making institutions, constitution-drafting and governance in general. Hence, for further insights, it is relevant to trace the roots of women’s under-representation in political leadership and elective representation back in history.

This pattern of imbalance can be directly linked to the British colonial era, when provisions in the 1922 Clifford Constitution stated that elections to the Legislative Council of Nigeria were for “Every male person who is a British subject or a native of the Protectorate of Nigeria, who is of the age of twenty-one years or upwards…”

This set off a process which saw Nigeria’s electoral and political party systems being built on male power and authority. There was collusion between the forms of colonial and indigenous patriarchy which saw colonial statutes and ordinances such as the one mentioned above, suit the male hegemony culture already being exhibited by early nationalists who excluded women from their mainstream political structures.

From then on, the evidence points to the over-representation of men in public life and domination of the political party structures, attendance of constitutional conferences and so on.

The early political parties such as the Nigerian National Democratic Party and the Nigerian Youth Movement built and nurtured systems which were centred round male political aspirations, interests and needs, with the women’s sections left to deal with mundane matters. With each wave of political parties from the nationalist era through to the First, Second, Third and the current Fourth republics, political institutions remain largely male-centric.

The historical evidence shows that during the 1950s, the new constitutions (Macpherson of 1951 and Lyttleton of 1954) allowed limited franchise for female taxpayers and later on, universal suffrage for everyone in the Eastern and Western regions of Nigeria. However, those women who were eligible to participate and contest in elections faced stiff resistance from their male colleagues. Indeed, this may account for why Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti is quoted as saying, her failure to win at the intermediate round of the Electoral College in 1951 was due to “male chauvinism.” Again, in June 1957, she reiterated this point in a statement to the press that “Women are used as election tools.”

During Nigeria’s First Republic from 1960 to 1965, only four women won elections. They were Margaret Ekpo, Janet Mokelu and Ekpo Young to the Eastern House of Assembly and Esther Soyannwo to the Western House of Assembly. Each woman is on record as having to stave off resistance by their male political associates. Thus, there is a historical pattern of systemic male bias and overwhelming exclusion of women from the country’s politics and governance, which as the data shows, still exists today.

Recommendations

As the data shows, despite their share of the population, women are being politically short-changed in the executive and legislative arms of government. There are wide gaps between the number of men and women who govern, hold positions of political leadership and occupy seats in the federal and state legislatures.

The answer to women’s substantive representation in the country’s public life lies in several measures. To reverse the continued marginalisation of women in politics and governance, the next administration should undertake the following:

- Conduct a forensic review on the status of women vis-à-vis their massive loss at the polls from 2015 to now, as well as their overall participation and representation in public affairs;

- Implement the April6,2022, Federal High Court ruling on 35% Affirmative Action in favour of women;

- Appoint an equal number of female and male ministers, or at the minimum, implement the 35% affirmative action for women in line with the ruling mentioned above;

- Ensure that the women are placed in substantive ministerial postsincluding those perceived to be traditional male portfolios.

- Implement and enforce the revised National Gender Policy 2021- 2026. Its key planks are designed to promote gender equality, political leadership and social inclusion across the three tiers of government. This is to address the massive losses experienced by women in the past three elections.

- Make social inclusion a key plank of its administration

- Provide (through an Executive Bill) the legal framework for the National Gender Policy for compliance and to ensure its enforceability

- Explore the principle of proportional representation to ensure that women who got as far as the ballot box are included in federal and state governments

- Promote a caucus of male gender champions in the parties, state and national assemblies to promote gender-responsive legislation;

- Promote the He-for-She Movement into an effective and vibrant coalition across religious and political divides;

- Sponsor legislations ontemporary special mechanism by the 10th National Assemblysuch as reserved seats for women in state and federal legislative institutions. This is known to work and has boosted women’s representation in legislatures in Europe, Latin America and United Kingdom. Closer to home, this kind of quota system has significantly altered parliamentary landscapes in South Africa, Tunisia, Namibia and Mozambique etc;

- Influence the reversal of all of the five rejected Gender Bills mentioned above, so they can be passed and signed into law by the president towards the socio-political empowerment and growth of girls and women;

- Pass the Gender and Equitable Opportunities Bill 2021 and alsoensure appropriate budgeting in order to effect to its implementation;

- Lead by example in the ruling party and then persuade other political parties to adopt gender quotas in their executive organisational and hierarchical structures as recommended by Uwais Report in 2007. In South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC) has perfected its voluntary party quota system and women form significant representation in its parliament.

Other stakeholders should also:

- Gender advocates must work on nomenclature that would be embraced by faith and culture leaders, so pursuance of gender-friendly legislation will face less resistance

- Conduct enlightenment programmes about the meaning of Gender Equality and its benefits for the empowerment of girls, women and Nigerians in general;

- Build a coalition of women (like in Senegal to achieve the Parity Law) across party lines and CSOs to organise, strategise to diminish the shadow of political, electoral and traditional patriarchy;

- Build on the positive wave of some political parties towards women’s representation in the governorship elections and lead by further example in local government councils;

- Reform the composition of Constitution Amendment/Alteration Exercises to make it more inclusive and reflect Nigeria’s population in order to achieve favourable constitutional guarantees for girls and women;

- INEC should consider sponsoring amendments to the 2022 Electoral Act which will ensure promotion and compliance of inclusivity on political party quotas and candidates’ lists etc;

- Work with journalists to eliminate bias of all forms against women politicians in traditional and social media spaces.

*Mrs Agunbiade, journalist, historian and gender advocate, is the author of the book: ‘Emerging from the Margins: Women’s Experiences in Colonial and Contemporary Nigerian History’

Sources:

- Dailytrust.com,Meet 48 Women who made it to state assemblies,’Saturday March 23, 2023

- International IDEA, https://www.idea.int

- https://www.inecnigeria.org

- Premiumtimes.ng,IWD 2023: Nigeria falling in women’s political participation, March 10, 2023

- Statista: Percentage of women in national parliaments in African countries 2022, www.statista.com

- Women Data Hub https://data.unwomen.org

- Women Liberty and Development Initiative, 2019

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Celestine Okereke | A feature of revenue distribution in Nigeria in the past few decades is that some federal agencies receive a percentage of the revenues they collect on behalf of the Federation.

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Douglas Okonko | Nigeria is currently facing diverse threats to its national security. These threats have serious implications for social, economic, and political development. According to a report published by Agora Policy titled, Understanding and Tackling Insecurity in Nigeria, “The nation is presently facing generalised insecurity with hardly any of its six geo-political zones spared from one form of insecurity or the other…” The country, the report said, “is practically under the gun on all fronts”.[1] Why is Nigeria under the gun on all fronts? There are several answers to this question, but one of them is that Nigeria’s borderlines are under-protected.

According to the Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS), there are 80 supervised entry ports, compared to 1490 known illegal entry routes[2]. The porous nature of Nigeria’s borders should get policy makers seriously worried. Through Sokoto, militia groups from Niger have been crossing the border into Nigeria unrestricted. Ambazonia rebels seeking safety from the government have also crossed the Nigerian-Cameroon border into border towns in Taraba State and Cross River State. There are occasions terrorist combatants and supplies have moved unhindered through the Nigerian-Chad and Nigerian-Cameroon borders.3 In the Southwest and Northeast regions, smuggling of contraband goods from Benin and Togo via Lagos, Kwara, Ogun, and Niger states persists.

Fig 1: Map showing Nigeria’s borders with neighbouring countries

The current state of our borderlines enables insecurity. As such, finding a durable solution is of utmost priority. This does not mean that efficient border security will resolve every security problem. Rather, it means that securing our borders by establishing a dedicated border force is a critical step towards ensuring national security. Here is why.

Rationales for a Dedicated Force

There are several reasons why we need a dedicated border force, but four of them stand out.

First, as stated above, Nigeria is currently battling generalised insecurity: none of its six geo-political zones is spared from insecurity. Although in decline, the impact of terrorist activities can still be observed in the Northeast4. ISWAP and Boko Haram continue to criss-cross Nigeria’s borders with Chad and Niger to perpetuate violence. According to Global Terrorism Index, 120 incidents of terrorism and 385 deaths were recorded in Nigeria in 2022.5Significantly, the activities of criminal gangs (bandits) in the North West and North Central regions caused more civilian deaths in 2021 than Boko Haram and ISWAP. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) also reported that, armed bandits killed more than 2,600 civilians in 2021.6The prevalence of insecurity in the North West and North Central zones could be linked to poorly policed borders. These porous borders have encouraged the spread of terrorist activities and weapons from Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. South West and South South are equally burdened by issues of insecurity.

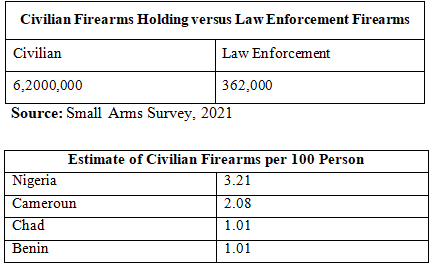

Secondly, the porous nature of Nigeria’s borders has accentuated the influx of arms into the country over the past two decades. This in turn has heightened the wave of terrorism, banditry, kidnapping, and other violent crimes. According to a report released by Small Arms Survey (SAS), civilians in Nigeria possessed more firearms than personnel of law enforcement agencies.7 SAS also reported that out of 100 persons, 3.21 carry firearms mostly smuggled from Sahel trafficking networks. It is also estimated that of the 500 million illegal weapons circulating in West Africa, 70% are domiciled in Nigeria.8

Source: https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/database/global-firearms-holdings

Relatedly, Nigeria’s porous borders and weak border security mechanisms pose a serious challenge to the fight against trafficking in illicit drugs. Unchecked entrance of illicit substances threatens public health as well as enhances criminal tendencies. The UNODC reports that14.3 million (14.4%) Nigerians aged between 15 and 64 years use illicit drugs.

The third rationale is that the current structure for securing our borders is fragmented and suboptimal. Nigeria runs a multi-agency border management arrangement spearheaded by the Nigerian Custom Service (NCS) and the Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS). Among other immigration and custom-related duties, these two agencies face the daunting task of securing West Africa’s third longest land borderline spanning 4045 km. Significantly, these agencies are under the supervision of different ministries, and they operate independently of each other. The NCS is under the Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning while the NIS is supervised by the Ministry of Interior. Although both agencies have a component of border security as part of their operations, the revenue-generating departments take precedence. This is at the expense of border patrol and national security. It gravely underscores the danger of diffused mandates for government agencies.

Lastly, the economic cost of a largely unprotected border is enormous. Nigeria’s porous borders have created an enabling environment for smuggling. Nigeria’s total revenue loss to smuggling activities is not clear but its impact on the economy can be felt. Millions of dollars that would have been generated through formal taxation have been lost to smuggling. According to a report by Chatham House, Oil theft in Nigeria is costing the country up to US$1 billion per month in lost revenues.9In 2010, 80% of Benin Republic’s domestic fuel consumption was smuggled from Nigeria, ata value in excess of US$863 million.10 This shows the level vulnerability of Nigeria’s borders. Smuggling has also distorted market prices and created unfair competition with locally produced goods. It has also led to the collapse of local manufacturing, loss of jobs and high rate of unemployment.

Recommendations for Operationalising the Border Force

Without a doubt, Nigeria needs a dedicated border force patterned after the United States Border Patrol (USBP), the Australian Border Force, the Border Security Agency of Malaysia, and Canada Border Services Agency. The impact of these dedicated agencies is well documented. For instance, the U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) apprehended 1,148,000 illegal migrants in 2019 and seized more than 112,000 pounds of assorted illegal drugs in 2022.11Securing the home from the gates is becoming a favoured tactic amongst nation-states. Nigeria can, and should align, with this increasingly approach with the creation of the dedicated border force, which should be backed by law. A bill (preferably an executive bill) thus needs to be initiated to authorise the creation and set out the operational framework of the force with the sole mandate of guarding Nigeria’s borders. The proposed force should be under the Federal Ministry of Interior.

The border force will require smart recruitment and elite training beyond what presently obtains. For example, the NIS has 25,303 staff members, out of which an undisclosed number of officers is under the command of the Directorate of Border Security. It is also not clear how many officers are under the Rural Border Patrol Operation (RBPO) of the NCS. In comparison, the U.S employs approximately 5, 000 border patrol agents to patrol 388 miles (624 km) of its southwestern border alone. To have comparable number of personnel per kilometre, Nigeria therefore will need to employ 32,395 border patrol agents for its 4, 043kmland borders. The point here is that the proposed border force must have adequate personnel for the demand of its mandate.

Although numerical strength plays a key role in security, a skilled and specialized number is better. Combating transnational crime will require the expertise of different security agencies. Before fresh recruitments into the suggested border force are implemented, the initial pool of officers should be drawn from existing security agencies to minimise cost and ensure the recruitment of officers with specific expertise and field experiences. Officers should be drafted from the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA), Defence Intelligence Agency(DIA), National Intelligence Agency (NIA), Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), Nigerian Custom Service (NCS), Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS), the Nigerian Police (NP) and the Nigerian Security and Civil Defence Corp (NSCDC).

The inter-agency composition of the Border Force will enable the establishment of a comprehensive operational picture in specific areas of trans-border crimes including drugs, arms and human trafficking, oil theft, piracy, and money laundering. Before take-off, however, there is the need for a plan to fully integrate and socialise the staff drafted from different agencies and presumably from different organisational cultures and orientations. This integrated approach will encourage a single chain of command and control. Qualified personnel should be trained by experts in the field of border patrol. Also, exchange programmes with countries that have successfully institutionalised a dedicated border force should be embraced. It is expected that the training and exchange programmes will build a strong and resilient border force with the required technical, tactical, and operational skills to operate and adapt to changing conditions.

Another key area is modus operandi for deploying officers of the force. Nigeria is bordered to the north by Niger, to the east by Chad and Cameroon, to the west by Benin, and the South by the Gulf of Guinea of the Atlantic Ocean. These borders vary in distance, prevalent crimes, and security threat levels. As such, the number of personnel deployed and the kind of personnel deployed (in terms of training and primary skill set) should be determined by these three factors (distance, prevalent crime, and security threat level). To maintain the high standard, professionalism, and integrity, oversight and accountability measures should be implemented to ensure that officers fully understand and abide by the operational guidelines of the force.

Securing Nigeria’s 4, 043km border requires more than just physical deployment—the force must leverage on modern technology to achieve its goals. Even for a dedicated border force, it is impossible to cover every inch of Nigeria’s borders. Advancement in modern ICT has enabled the incorporation of technology into border security possible. Technology can be used to detect, identify, classify and communicate threats in “hard-to-reach terrains”. Since 2017, the US Customs and Border Patrol received more than $700 million in funding for border technology.12Even though the proposed dedicated border force may find it hard to attract such a huge investment in the interim, it still needs substantial investment in modern technology for it to be effective. Before the purchase and deployment of technology, the border force should develop a clear strategy and plan that covers its technological needs, and describes the need and appropriate area of deployment. Officers should be trained on how to best use acquired equipment or facility. Acquired technology should be regularly upgraded and monitored to avoid compromise. Some of the available border technology that could be used include unmanned drones, relocatable towers, sensors, and mobile land-based radar trucks.

Advancement in technology should not take away the place of infrastructure. Border infrastructure includes not just fencing and other physical barriers, but also roads that provide access to the borders and areas along the borders for quick response. Sector stations and other operating bases of the border force should be situated at or close to key illegal entry “hotspots” to accelerate response time. Preferably, these stations and bases should be movable in anticipation of route diversion by criminals.

Conclusion

Porous borders have been identified as a major driver of insecurity in Nigeria and if allowed to linger will cause further damage to human security and further stifle socio-economic development. Nigeria’s weak borders call for the establishment of a dedicated border force with the needed legal backing, expertise, technology, training, infrastructure, and intelligence to detect, identify, classify, prioritise, and mitigate security threats along its expansive borders.

*Okonko is a Research Officer at Agora Policy

Foototes

[1] Agora Policy, “Understanding and Tackling Insecurity in Nigeria”, Agora Policy Report, No.2, Nov, 2022, p,8

[2] AKin Akibola, “Immigration decries inability to effectively man borderlines”, Channels Television, May 24 2022,https://www.channelstv.com/2022/05/24/immigration-decriesinability-to-effectively-man-borderlines-1490-illegal-entry-points/, Accessed 22 March, 2023.

[3] Agora Policy, “Understanding and Tackling Insecurity in Nigeria

[4] The impact of terrorism continues to decline in Nigeria; with total deaths falling by 23 per cent, decreasing from 497 in 2021 to 385 in 2022. The number of terrorist attacks in Nigeria also fell considerably, with 120 incidents recorded in 2022 compared to 214 in 2021. This is the lowest number of terror attacks and deaths since 2011.

[5]Global Terrorism Index 2022, “Measuring the Impact of Terrorism”file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/GTI-2022-web_110522-1.pdf, Accessed, March 30, 2023.

[6] Aaron Karp“Estimating Global Civilian-held Firearms Numbers”, Small Arms Survey, Briefing Paper, 2018 p,10

[7]Tribune Online, “Insecurity: 70 percent of illegal weapons in West Africa domiciled in Nigeria”, April 19, 2021, https://tribuneonlineng.com/insecurity-70-per-cent-of-illegal-weapons-in-west-africa-domiciled-in-nigeria-%E2%80%95-unrec/, Accessed 21, March, 2023.

[8]Royal Institute of International Affairs (2013). Maritime Security in the Gulf of Guinea. Report of the conference held at Chatham House, London, 6 December 2012. Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Africa/0312confreport_mariti mesecurity.pdf

[9]UNODC, “Transnational Organized Crime in West Africa: A Threat Assessment. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime”.https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-andanalysis/tocta/West_Africa_TOCTA_2013_EN.pdf,

[10]John Davis, “Border Crisis: CPB’s Reponse”, https://www.cbp.gov/frontline/border-crisis-cbp-sresponse, Accessed, 22 March, 2023.

[12]Homeland Security, “CBP has Improved Southwest Border Technology”, February 23, 2021, https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2021-02/OIG-21-21-Feb21.pdf, p.2

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Adebayo Ahmed | The question of food is one that is now on everybody’s lips in Nigeria. The food situation has worsened significantly in the last year partly driven by efforts to turn the economy around in terms of petrol subsidy removal and the foreign exchange market reform. The situation seems dire with increasing cases of violence and civil unrest associated with hunger and with fears that if the situation is not well handled, the country could be headed to the same type of civil unrest witnessed with the COVID19 palliatives in 2020 or worse.

Fig 1: Prevalence of moderate to severe food insecurity. Source: FAOStat

Although the food issue is, or at least should be, top of the agenda right now, the challenge of food security is not really new to Nigeria. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), about 34.7% of the population was experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity in the 2014 to 2016 reference period. By any standard, 34.7% was already high. However, the situation worsened almost continuously each year so much so that by the 2020-2022 reference period, an estimated 69.7% of the population was experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity, with 21.3% in the severe category. This worsening trend is backed up by data by the Cadre Harmonise which estimates that 31.5 million households in 26 states plus the FCT are expected to be in crisis in the “lean” season between June and August of 2024. This is up from the 26.5 million people estimated to have been in crisis for the same period in 2023. The total number nationwide is likely higher given that the Cadre Harmonise looks at only 26 states and the FCT. Importantly, the distribution of hunger is nationwide with almost no state spared. The combination of worsening hunger and national spread means that Nigeria is near the top of countries with hunger problems. For example, Nigeria ranks 109th out of 125 countries on the Global Hunger Index1 and 107th out of 113 countries on the Global Food Security Index2.

The rising hunger is not without consequences. According to the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, an estimated 37% of Nigerian children under five years of age are stunted, meaning they do not develop to their full potential. According to UNICEF3, an estimated two million children already suffer from “severe and acute malnutrition”. This likely contributes to our under-five mortality rates of 107.2 per 1000 live births, the third highest of all countries compiled according to data from the World Bank4. Given our population relative to others, it implies that globally, a large number of children who die before the age of five from reasons, including hunger, are from Nigeria. Although the current situation seems more dire than normal, it is important to accept that this hunger crisis is not a one-off problem.t is a problem that has worsened continuously over a long period of time.

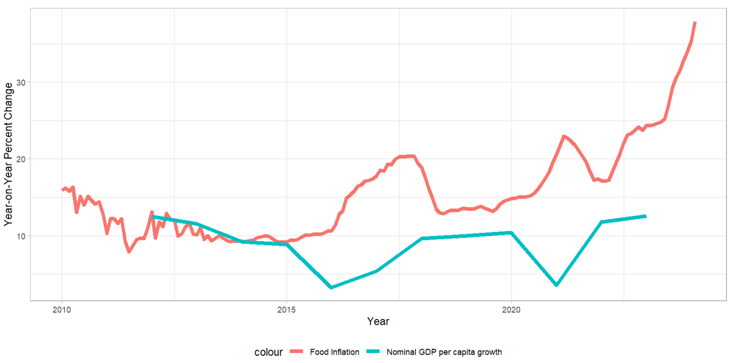

Fig 2: Food Inflation and Nominal GDP per capita growth. Source: NBS and Author’s calculations

Causes of Food Security Crisis

The causes of the food security crisis are actually very simple and can be thought of from two perspectives. The first being that food prices have risen systematically faster than household incomes. As is clear from Figure 2 above, average incomes have grown significantly slower than food prices since 2015. This means households have been getting continuously squeezed and food has become increasingly unaffordable. The measure of average income used here is simply average nominal GDP per capita but if you incorporate income inequality then it is likely you will see a tighter squeeze at the lower end of the income ladder. Things have gotten worse in the last year but it should be clear to all that the situation has been brewing for almost a decade.

The causes of rising food prices have been rehashed over and over again but they are worth repeating regardless. Monetary policy has been loose, leading to the classic demand push inflation of more money chasing fewer goods. Trade policy has been restrictive, leading to supply disruptions which have put upward pressure on food prices. Interstate logistics continues to be challenging, leading to a wide variation in prices across the country and household paying more than they could have been paying if logistics were better. Farming techniques continue to be “traditional” and rain-driven, leading to mostly low agricultural yields. Climate change has made it more difficult for farmers to produce reliably. The security situation has continued to worsen especially in key agricultural areas, limiting access to usually productive farmlands. And so on.

The last point highlights the second perspective for the cause of the worsening food crisis: livelihoods i.e. whatever people do to earn a living. To be clear, livelihoods here does not refer only to those of farmers, but to barbers and street vendors, and bankers, and so. And as can be seen from the 2023 Cadre Harmonise which estimated the distribution of food insecurity by state, there are more people under hunger stress in Lagos State than in any other state. The majority of people in Lagos are not employed in the agriculture sector. Food prices may rise fast enough that even people whose livelihoods are not disrupted can become food insecure. But the other perspective is that people’s livelihoods may be disrupted so that even with the same food prices, they no longer have the capacity to afford to keep themselves out of food insecurity.

The disruption to livelihoods in rural communities is a good place to start in thinking about this perspective. The deteriorating security situation and climate change are both combining to make earning a livelihood from agriculture increasingly difficult. Farmers in many communities cannot access lands because of terrorists, bandits, kidnappers, and so on. In other places where they can access land, climate change is leading to more irregular weather, making their production more volatile thus impacting their livelihoods. On the urban front, the absence of decent job growth and almost consistent economic shocks, from the 2015 oil price crash to COVID19, to recurring foreign exchange crises, have put a similar dent on livelihoods and income growth. Both factors mean that almost everyone is now feeling the squeeze, though the poor (who are in the majority) are disproportionately impacted.

The Path Out of the Crisis

Given that the crisis is seemingly largely about affordability, the path out of the crisis likely involves tackling affordability both immediately and in the long-term. In terms of immediate responses, the key is to on the one hand get money directly into the pockets of households, and on the other hand take action to put downward pressure on food prices. The government, at the federal, state, and local levels, should have a lot more money flowing to their coffers given that petrol subsidies were removed, and that the weakening of the national currency should mean more Naira from crude oil revenues. Re-directing some of this windfall directly into the pockets of Nigerians would automatically improve their capacity to afford food and will do so immediately. There has been talk of a cash transfer programme by the Ministry of Finance with 15 million households targeted. It is however time for more action and less talk. And of course, states and local government areas that are also benefitting from the windfall should not be let off the hook.

Some may argue that there is a risk of putting even more pressure on inflation if more money is funneled directly to households. This does not have to be the case in practice. If the social transfers are funded by already existing revenue and not by an increase in money supply through increased domestic debt or central bank financing, then the impact on inflation should be minimal.

And of course, putting money into the pockets of households however has to go hand in hand with other attempts to increase food supply and put downward pressure on food prices. On this, there are many short-term options on the table. Can we do anything to immediately reduce the portion of food prices that is due to logistical challenges and corruption on the highways? Does it make sense to have a sixty to seventy percent tariff plus duty on imported wheatand rice, at a time when food prices are relatively sky-high and unaffordable?

Dealing with the currency issues, which has resulted in the Naira weakening so much that most food items in Nigeria are cheaper than in some neighbouring countries also needs to be resolved. International demand for food items from Nigeria has increased putting upward pressure on prices. A weakening Naira means that food traders would rather collect foreign currency than sell to domestic consumers. As the currency weakens further, domestic prices for tradeable food items would have to adjust which would worsen the affordability challenges. The problems on the macroeconomic front transmit to very real challenges. Stabilising things on the macroeconomic front, specifically the exchange rate, is therefore a necessary part of the immediate measure to deal with the challenge.

On a related note, it may be tempting to try to limit the impact of the exchange rate on food prices by other means such as trying to limit cross-border trade or trying to increase domestic supply to keep domestic prices lower than prices in neighbouring countries. Both temptations are likely to be unsuccessful. We have a long history of trying and failing at restricting regional trade and the only likely result of attempts to do that now would be more smuggling and more illicit and informal trade. More importantly, restricting trade today would disincentivise farmers from doing all they can to boost domestic output tomorrow and reap the rewards of demand from international markets. The same can be said for releasing food items from strategic reserves. Given the strong demand from neighbouring countries, the food items would likely simply flow there, unless maybe they are distributed directly to households.

Longer-term Solutions

Beyond the immediate term, the longer-term solutions have to revolve around reversing the trends observed in Figure 2. That is, working to ensure that average incomes grow faster than food prices.

Conventional macroeconomic management is the starting point for ensuring that food inflation does not spiral out of control like it has done in the recent past. This means having money supply that is not growing systematically too fast, and continuing to diversify exports to minimise the risk of currency crises. In the face of macroeconomic challenges, even excellent policy on all other fronts will struggle to yield the desired results.

Improving incomes and resilience of households is the second major long-term agenda. The richer the household, the more likely they will be able to cope with food price shocks. The institutionalisation of social protection will also help ensure that households have something to fall back on in the event of more serious shocks. In this context, it is important to realise that improving resilience is not just about rural farmers but also about urban poor households, or those who are at risk of falling into poverty. For urban households, this means better jobs.

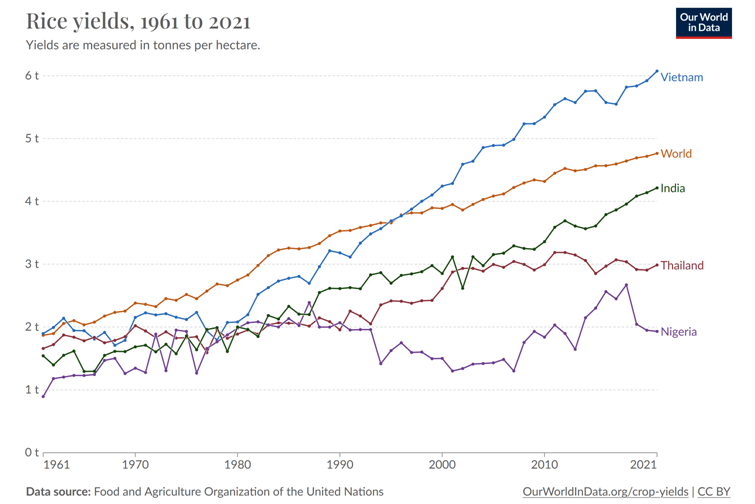

Fig 3 - a; Rice yields

Fig 3 - b: Tomato yields

Fig 3 - c: cereal yields

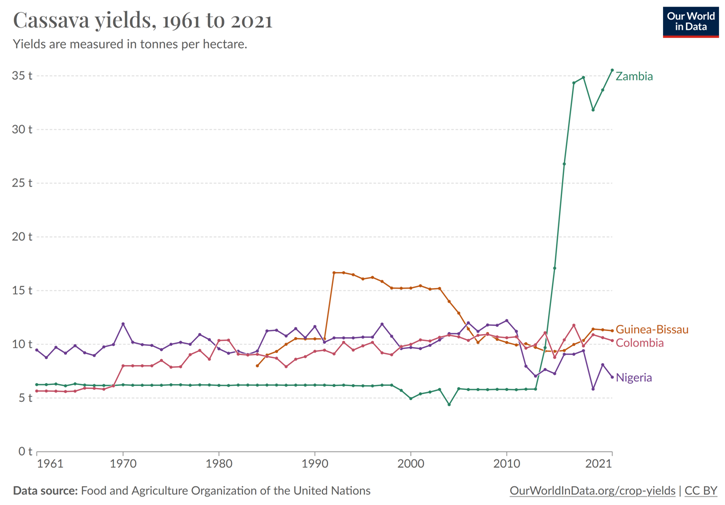

Fig 3 - d: Cassava yields

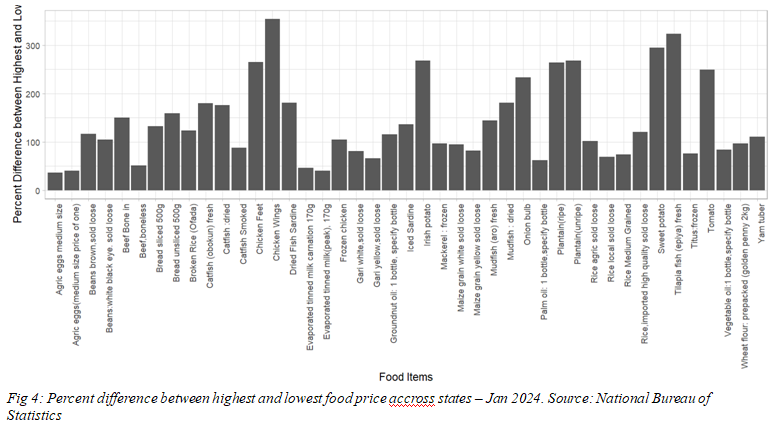

For rural agriculture-based households, this means improving productivity. Agricultural productivity is still relatively low and this is one of the foundations for domestic supply problems and high food insecurity in rural communities. As is clear from the yield on rice, tomatoes, cereals, and even cassava, yields in Nigeria are relatively very low. Improving productivity should therefore be the number-one agenda. This agenda would involve transforming farmers from subsistence farmers who farm to survive, to entrepreneurs who farm to get incomes. Turning farmers to entrepreneurs would have to involve investments in yield-improving infrastructure such as irrigation facilities, improving seedlings and seeds’ availability, improving knowledge about best practices through better extension services, improving rural security, improving resilience to climate change, improving farm-to-market infrastructure and logistics. And so on. As shown in Figure 4, the difference in prices between states is so large that just cutting logistics costs from moving food around can have a significant impact on reducing prices.

However, working to improve domestic supply and reduce costs is not enough. It is also important to build on and improve resilience to shocks in supply. This does not only involve producing more food. It involves two other factors, the first of which is storage. Storage, in the simplest of terms, is keep food when things are good to eat when things are not so good. The cyclical nature of our weather patterns in Nigeria means that we are no strangers to the importance of food storage, even if occasionally we like to throw around words like hoarders and saboteurs. Improving the quality and organisation of storage facilities should mean we are better able to cope with shocks to supply.

The second factor is trade. International trade. Leveraging international trade and building strong trade networks essentially ensures that supply is more resilient. For example, if domestic demand for a particular food item is more than current domestic supply, perhaps because the rains did not arrive on time, or because a flood damaged some output, or because the farmers techniques were not that great, international supply helps minimise the risks that the demand-supply gaps would cause scarcity or price increases. The same applies for situations when supply outstrips demand. International trade ensures that excess supply can go somewhere else and not lead to a price collapse which would also hurt livelihoods of farmers.

The second factor is trade. International trade. Leveraging international trade and building strong trade networks essentially ensures that supply is more resilient. For example, if domestic demand for a particular food item is more than current domestic supply, perhaps because the rains did not arrive on time, or because a flood damaged some output, or because the farmers techniques were not that great, international supply helps minimise the risks that the demand-supply gaps would cause scarcity or price increases. The same applies for situations when supply outstrips demand. International trade ensures that excess supply can go somewhere else and not lead to a price collapse which would also hurt livelihoods of farmers.

Getting to grips with the food security challenge is urgent but there are enough tools available to the government to turn things around and ensure that we do continue to be one of the basket cases of hunger in the world. But it will require quick action to do things today, and the foresight and the stamina to undertake more long-term, strategic and coordinated actions to remove Nigeria permanently from the hunger map. The current episode of high food prices should raise the status of the lingering food security challenges in Nigeria and propel policy makers to take immediate and longer-term decisions to sustainably reverse the trend. Food security should be seen as national security.

Photo Credit: Mansur Ibrahim

Footnotes

[1] https://www.globalhungerindex.org/nigeria.html

[2] https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/explore-countries/nigeria

[3] https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/nutrition

[4] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT?most_recent_value_desc=true

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Ayobami Ayorinde | In the last two weeks, the Federal Government unfolded some emergency measures in the agricultural sector. On July 10, the Minister of Agriculture and Food Security,

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Samuel Ajayi | On 4th February 2025, President Bola Tinubu signed the North Central Development Commission Bill into law, which brings to six the number of zonal development commissions in Nigeria. With the South South Development Commission—whose bill is yet to be signed—also receiving allocation in the 2025 budget recently passed by the National Assembly, this number is likely to rise to seven soon.