By Adebayo Ahmed | The new dispensation combined with quick policy actions on fuel subsidies and foreign exchange, as well as the arrest of the suspended central bank governor, has brought the question of monetary policy to the front burner. With President Bola Tinubu announcing during his inaugural speech the need to “clean” the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) as well as the need to reduce interest rates to promote MSME-led growth, the question therefore revolves around what the CBN has been doing wrong, and what is the way forward.

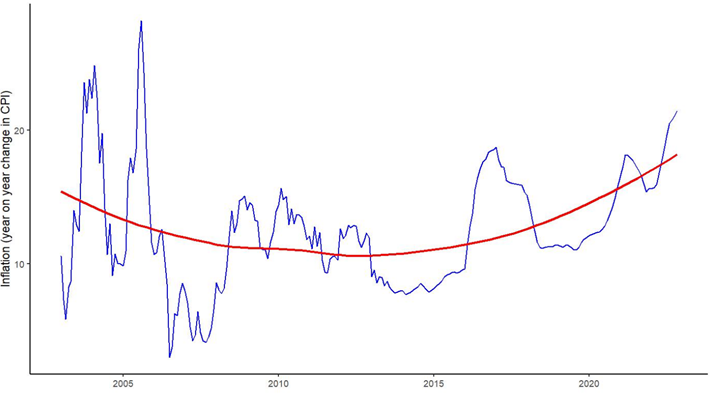

Fig 1: Inflation. Source: National Bureau of Statistics

The backdrop to this question is the uncomfortably high and rising inflation which hit an 18-year high of 22.41% in May. Inflation at over 22% is a big challenge for any economy. It means that prices double in less than four years. It means that salary earners lose 22% of their purchasing power every year. It means that the government would need to generate 22% more revenue just to provide the same public services. It means that the Naira will likely weaken by 22%, less whatever global inflation is, in the next year. Inflation at 22% means that the challenge of moving the Nigerian economy forward and improving the lives of ordinary people forward is significantly harder.

This high inflation is especially worrying for food which, at nearly 25%, means that the poorest who as at 2019 already spent roughly 60% of their incomes on food, are in a very difficult position. When combined with other recent policy efforts, such as the removal of fuel subsidies, the seriousness of the challenge should be apparent as inflation has been projected to surge even higher.

Given that keeping prices “stable” or keeping inflation low is the core monetary policy objective of the CBN, then it is easy to make the case that the central bank has been, and is, failing its core mandate. If you add popular annoyance against exchange rate issues, then the scorecard is likely to be very poor.

In this note, we will argue that the failure is due to the CBN’s misunderstanding of its powers in terms of what it can and cannot do. This misunderstanding has led it down the unconventional policy route which, as expected, has resulted in higher inflation and not much else. That misunderstanding however is a good lesson for the CBN going forward, especially in the context of the new government’s zeal to set a more credible path for monetary policy.

The big trade-off in monetary policy: Taming inflation versus promoting growth

First, a simplification of the big trade-offs when thinking about monetary policy, which is really all about controlling and managing the money supply to ensure that there is just enough money in circulation to incentivize real economic growth in a sustainable way. Of course, money (today) is really just a piece of paper (or a digital record) that has no intrinsic value. That piece of paper does not cause rain, or fight terrorists, or reduce bottlenecks at the ports, or teach young people physics. In economics we like to say that in the long-run money is neutral. If you wanted more water for agriculture, you would need to build irrigation facilities; and if you wanted to fight terrorists disrupting your economy, you would need more policing and intelligence.

This neutrality of money has very important implications for monetary policy. The first is that higher levels of money supply for a given level of economic activity just means higher prices (also known as higher inflation). Imagine a hypothetical yam-eating society in which their central bank decided to double everyone’s income by a cash transfer but the number of yams available, the real yam economy, remained the same. The only outcome will be higher prices for yams or yam inflation.

In practice, economies are a lot more dynamic but the principle is the same. Controlling the amount on money supply is the key factor behind managing inflation. If your money supply grows too fast relative to your real economy then you have higher inflation, and vice versa. Ergo, if we observed that inflation was getting too high then the expected policy response would be to reduce the growth of money supply.

There are many tools for reducing the growth of money supply but the conventional primary tool is through an increase in interest rates. The logic is simple. At the margin, higher interest rates make borrowing more costly which means credit, to the private sector or governments, should reduce, and which means money supply reduces as well. On the flip side, higher interest rates also incentivize banks to park money at the central bank to collect more interest which also tends to reduce money supply. There are various other channels but in general higher interest rates tend to reduce money supply.

But higher interest rates also have other effects. Higher interest rates tend to slow down the economy. If you think of the channel through slowing credit growth then it is pretty straightforward to see how. So, the question then becomes, when faced with higher-than-normal inflation, should policymakers choose to allow higher inflation or raise interest rates to reduce inflation, even if it limits economic growth or employment?

The answer is almost always to opt for lower inflation. The first rationale behind this is because inflation affects everything, even the interest rate itself. Think for instance of our yam economy and imagine inflation was 25% a year. What this would mean is that even if interest rates were as high as 20%, the providers of credit would still be losing value. In that economy, if a person loaned out the equivalent of one yam, at the end of the tenor, the principal plus interest would not be able to buy that same yam. In essence, real interest rates would be negative. So, you would need even higher interest rates just to incentivize people to stand still in real terms.

The same dynamic works with exchange rates in an economy with higher inflation. Imagine inflation in Naira-denominated yam economy was 25% but inflation in our neighbours’ CFA-denominated economy was only 1%. It would mean the Naira would have to depreciate by about 24% relative to the CFA just to stand still. If it didn’t, then yams from our neighbors would be systematically cheaper and everyone would opt for them and our economy would suffer.

The impact of inflation is so ubiquitous, from wages to government spending to interest rates to exchange rates, that when faced with a choice, monetary policy almost always has to opt for lower inflation even if it comes with some costs.

But that is not all. Imagine our yam creditor who has to decide what “real” interest rate to charge to ensure that she doesn’t end up losing value at the end of the term. She has to guess what inflation in the future would be. If she thinks inflation will be high then she has to charge a high interest rate to make up for it. On the other hand, if she thinks inflation will be low, then she can charge a lower interest. In essence, her expectations about inflation in the future affect what she does today, and therefore affects what really happens in this yam economy today. What this means is that, even if nothing happens, if people start to expect that inflation will be high then there are consequences to that.

From the perspective of monetary policy, this means that it is not enough to choose lower inflation, but people need to believe that you will choose lower inflation and do what needs to be done to tame inflation. If people start to believe that inflation will be higher, then people start to act as if inflation is high and that results in all the consequences of high inflation even if nothing significant happens.

Supply shocks and optimal monetary response

An expansion in money supply is not the only thing that can cause inflation. Supply shocks can also have impacts on prices and inflation as well. Think about our yam economy and imagine some goats came and ate up half the yams. Given the same amount of money supply in circulation it will simply mean that prices will go up, otherwise known as higher inflation.

What should monetary policy authorities do about supply shocks? The conventional wisdom is if you think those shocks are temporary then you can try to just ignore them if they aren’t too large. But if you think those are not “shocks” but permanent changes in supply, then you have to manage money supply to reflect those permanent changes. For example, in our yam economy where goats ate half the yams, the ideal monetary response would be to reduce the money supply to fit the new reality of an economy that is only half as large as it used to be.

What monetary policy authorities typically do not do is to try to directly tackle those supply shocks with money. Remember that money is neutral and you typically cannot use money to kill goats, or construct dams, or train teachers, or neutralize COVID. It does not mean that other parties cannot do this to help tackle inflation. Other parties can. The convention is to let the other parties tackle supply shocks because in most cases the shocks are not only about money.

Even where money could be impactful, the conventional wisdom is to let the parties that are best able to find and channel that money, usually the financial sector or the government, to do what they are good at. This is because if those issues are tackled with monetary policy, then you will have to weigh the impact against the costs of higher inflation. In general, higher inflation is always worse.

In essence, even though supply shocks can have an impact on inflation, the monetary policy response to supply shocks ideally would be to be more focused and ruthless in managing money supply.

CBN and the wages of unconventional monetary policy

The recent history of monetary policy in Nigeria can be described simply as the CBN trying to use monetary policy for things that monetary policy could not do, and choosing to focus on other issues while abandoning its inflation mandate. As expected, the outcome from not choosing lower inflation has been higher inflation without any real impact on the many other things it tried to do because, you know, money is neutral.

Many may have forgotten but at his inaugural speech in 2014, the suspended CBN governor, Mr. Godwin Emefiele, wrote that “the Central Bank [could not] afford to sit idly by and concentrate only on price and monetary stability”. He essentially promised to use the CBN for developmental activities such as “credit allocations and direct interventions in key sectors of the economy”.1 To be fair, at the time in 2014, inflation was somewhere around 8% and if inflation is low then there is scope for either monetary expansion or interest rate reductions. The governor chose the latter, and chose to expand money supply not through the financial sector, which is typically the better allocator of credit, but directly through its interventions and eventually lending to government.

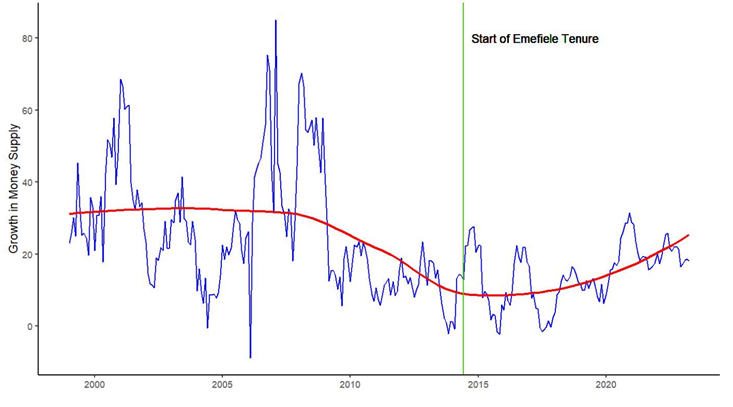

Fig 2: Growth in money supply (M2) with trend in red. Source: Central Bank of Nigeria2.

The CBN under his direction, changed from what had been a relatively successful decade of limiting money supply growth which resulted in single digit inflation, to increasing the growth of money supply. As Figure 2 shows, regardless of what else was happening in the economy, what is clear is that there was a change of trajectory and money supply started to increase under his watch. Money supply was of course completely under the control of the CBN. As we remember from our crash course in monetary policy, more money supply in a similar-sized real economy, simply means higher inflation.

Fig 3: Inflation with trend in red. Source: National Bureau of Statistics.

Yes, there have been supply shocks revolving around foreign exchange, COVID, climate change, and other security complications and so on. What is however clear is that the underlying inflation trend has been increasing, in spite of these shocks. Even if you ignore food inflation, which is typically more volatile and in our case dependent to a large extent on the weather, and focus on core inflation, the story is the same. As discussed earlier, supply shocks can and do lead to inflation but the implication is that there was even less room for messing around with monetary policy.

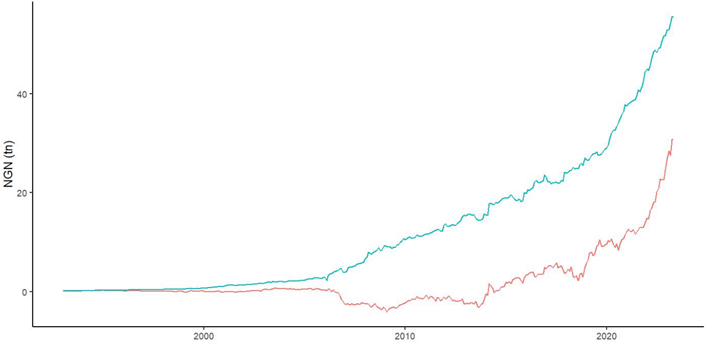

Fig 4: Credit to the government and Money Supply (M2). Source: Central Bank of Nigeria

The first culprit is the expansion of lending to the Federal Government which resulted in a direct increase in money supply, all else being equal. As became clear during the final days of the President Muhammadu Buhari administration, this lending was significant with N22.7tn of this Federal Government outstanding debt securitized in May.

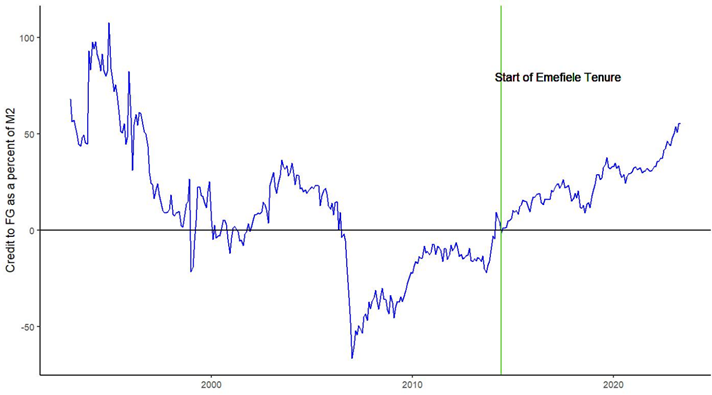

Fig 5: Outstanding Credit to the Government as a percent of total money supply (M2). Source: Central Bank of Nigeria.

For context, this was equivalent to over 40% of the total money supply3 as at April 2023. You can draw a straight line from the CBN’s financing of the Federal Government to the expansion in money supply and then to rising inflation. Previous CBN regimes had worked very hard to reduce the size of lending to the government with the resulting benefits of lower inflation for the economy as is clear in Figure 5. In fact, under the Lamido Sanusi regime the stock of Federal Government debt at the CBN was technically negative. However, that trend reversed with the outstanding debt becoming positive and growing astronomically under Emefiele.

The CBN’s special interventions also contributed their share. Figures are hard to come by on this, but there were reports of about N1.5tn to the anchor borrowers' programme, another N1.5tn on the power sector, N220bn to the textile sector, and so on. All these contributed directly to the growth of money supply and therefore rising inflation. You can argue about the impacts of these interventions but it is unlikely that whatever impacts they had or did not have were large enough to cover the negative impact of higher inflation.

The CBN tried to manage some of this by increasing the Credit Reserve Ratios (CRRs), the fraction of funds that banks have to hold in reserve, but in an arbitrary ad-hoc way with different CRRs for different banks. Although this might have slowed the growth of money supply, it was not enough given the scale of the expansion. There were also questions on the legality of implementing a CRR policy in such an ad-hoc way.

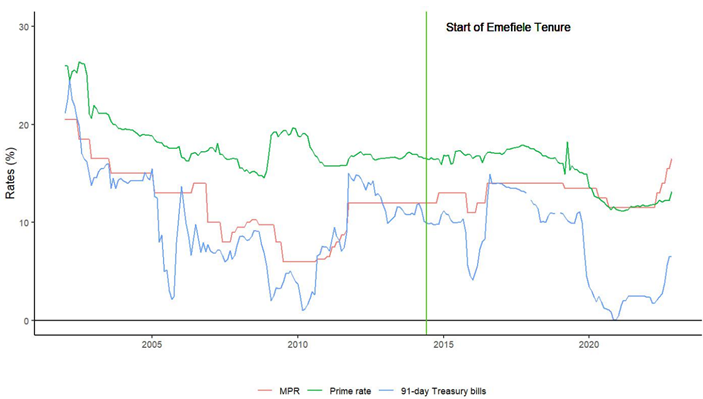

Fig 6: Interest rates. Source: Central Bank of Nigeria

The second culprit in the woe of unconventional policy was trying to force interest rates down even while inflation was going up. If you look at the monetary policy rate in Figure 6, which is supposed to be a signal for CBN’s interest rate policy, you would be forgiven for thinking that it did not change much. But in practice the CBN used administrative action to force rates down. If you look at the actual prime interest rate or the rates on government bonds and treasury bills then the direction of rates is clear. The action on rates started a long time before COVID so it cannot simply be blamed on the pandemic.

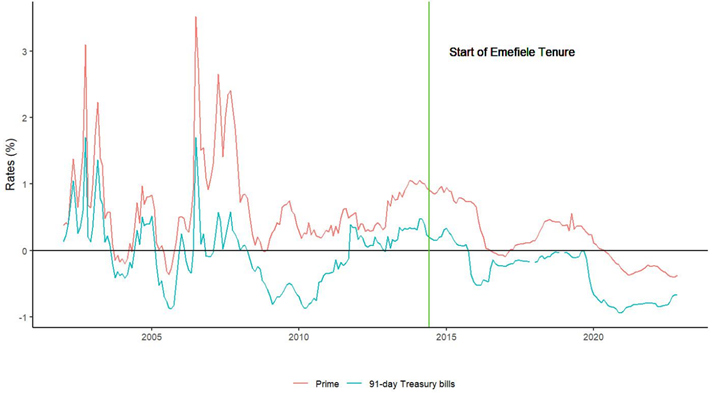

Fig 7: Real interest rates. Source: Central Bank of Nigeria and Author Calculations3.

The consequence of the action to reduce interest rates even during a period of higher than ideal inflation was that “real” interest rates became and are still negative. As we learned from our simple crash course in monetary policy, negative interest rates mean people should take their assets elsewhere. This puts even more upward pressure on inflation.

Fig 8: Inflation Perception and Expectations 4

A consequence of the CBN abandoning conventional for the unconventional was that people began to doubt the CBN’s ability to control inflation. As is clear from Figure 8, the public’s expectation of future inflation began to rise. If you recall, even if nothing else happened, once people start to believe that inflation will be higher in the future, then that makes the work to keep inflation in check even harder.

So, what’s the way forward?

The starting point is for the CBN (and given the current circumstances the executive also) to recognise the scale of the inflation challenge and the importance of getting inflation under control. As long as inflation remains high, every other objective, be it the quest for exchange rate stability or the president's agenda for increased cheap lending to MSMEs, will be much more difficult to achieve. The CBN needs to remember that its primary monetary policy objective is to keep inflation in check.

Given that inflation is currently much higher than ideal, the direction of monetary policy has to be to tighten or reducethe growth of money supply. This also means that interest rates will likely have to go up. How far up? At least to the point where “real” interest rates are no longer negative, but maybe even higher.

These actions to reduce the growth of money supply and increase interest rates are likely to be complicated by all the underhand administrative measures which were put in place to force rates down or to limit money supply growth through the back door. For example, the many administrative measures have meant that the monetary policy rate has recently no longer influenced interest rates either for government securities or at the banks, making the monetary policy committee effectively meaningless. The unwinding of the ad-hoc CRR policy, which means money refunded to banks, will also have unintended effects if not managed. The CBN will need to unwind most of these ad-hoc measures.

Given the misdirection by the CBN over the last few years, there may a tendency for the government to want to take closer control of monetary policy. This will likely be counterproductive as it has been demonstrated here in Nigeria and in other countries where governments tend to want to use monetary policy for other non-inflation objectives. Which is the underlying problem that the CBN faces today.

A better way forward would be to strengthen the monetary policy committee and place limits on CBN’s actions that fall beyond the scope of its regular monetary policy actions. One option here would to increase the number of independent members of the committee (currently only four out of 12) and/or reduce the members from the CBN and other government agencies. For instance, there is no real reason why the deputy governor for corporate services, a largely administrative role, should be voting on monetary policy. Increased oversight, to ensure that the CBN actually implements the decisions of the monetary policy committee, would also help strengthen the credibility of the CBN.

Finally, the direct sources of expansion in money supply witnessed over the past decade, specifically the ways and means financing of the government and the myriad of intervention funds will have to stop. Else, it would be equivalent to removing the plug to drain liquidity from the bathtub while at the same time turning on the taps.

As demonstrated above, not everything is within the purview of central banks. For instance, supply shocks, which are beyond the remit of central banks, are also known to drive up inflation. This in essence means that other actors, such as the governments at both the federal and state levels, can take actions to influence supply positively, which should put downward pressure on prices and therefore reduce inflation.

Lessons can be learnt from efforts aimed at tackling rising inflation around the world. Yes, central banks took actions to tighten monetary policy as they were required to but other actors took a variety of actions to put downward pressure on prices as well. For instance, the US govt took measures to ease supply chain logistical challenges that were blamed for rising logistics costs. The UN facilitated the exports of wheat and fertilizer as part of the Black Sea grain initiative to put downward pressure on global food prices as a result of the conflict in Ukraine. In Germany, the government increased investment in public transportation to manage rising transport costs. And so on. The lesson for Nigeria is that even though the CBN has a key role to play in managing inflation, and needs to play its part, the government can also make a significant difference.

For instance, improving security on farms and tackling logistics bottlenecks around moving food across the country will put downward pressure on food prices and reduce food inflation. Promoting regional African food trade, by maybe re-opening the borders and cutting tariffs on imported food will reduce food prices and reduce inflation. From a government finance perspective, improving tax collections and reducing the need for large fiscal deficits which then need to be financed will reduce inflation. We can go on and think of a plethora of actions which governments at the federal, state, and local levels can take to improve the “real” supply-side and therefore reduce inflation. In economics, we call them “structural reforms” which boost supply.

The reality of the last few years is that there is no pain-free way out of Nigeria’s inflation quagmire. But, as with the case of the fuel subsidy and the foreign exchange restrictions, the rationale for early action is clear even if there will be costs to it. From a monetary policy perspective, one of the costs is the necessary higher interest rate environment. But it will be worth it if we get inflation back under control.

Photo Credit: premiumtimesng.com

Footnotes

[1] “My agenda as Nigeria’s Central Bank Governor, By Godwin Emefiele” - https://www.premiumtimesng.com/opinion/162063-my-agenda-as-nigerias-central-bank-governor-by-godwin-emefiele.html?tztc=1

[2] The red line is a standard Loess function to distinguish between the trend in money supply growth and the cyclical component.

[3] Defined as M2 Money Supply. Source: Central Bank of Nigeria

[4] Real interest rates calculated as the difference between the nominal rates and the year-on-year change in inflation.