Policy Insight

- Details

- Policy Insight

By Wale Thompson | Last week, the Federal Minister of Finance, Budget and National Planning, Mrs Zainab Ahmed announced the receipt of presidential approvals to ‘securitize’ Ways and Means (W&M) loans totaling NGN20trillion which the Federal Government (FG) owes to the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN). In economics, Ways & Means is the unrestrained central bank financing of fiscal deficits or more simply excessive government borrowing from the central bank to plug financing holes in annual budgets. In her briefing, the minister noted that the securitization would take the form of the issuance of FGN debt instruments of a 40-year tenor and at an interest rate of 9 percent to the CBN in lieu of the amounts owed. Upon completion, the transaction would represent the single largest addition to Nigeria’s federal government debt which would rise to N55.7trillion from the N35.7trillion reported in June 20221.

So, what is this all about?

Securitization is a finance term which refers to the process in which certain assets (usually obligations to receive money e.g. loans) are pooled in a manner that they can be repackaged into interest-bearing securities that can be sold in the capital market. The interest and principal payments from the assets are passed through to the purchasers of the securities.

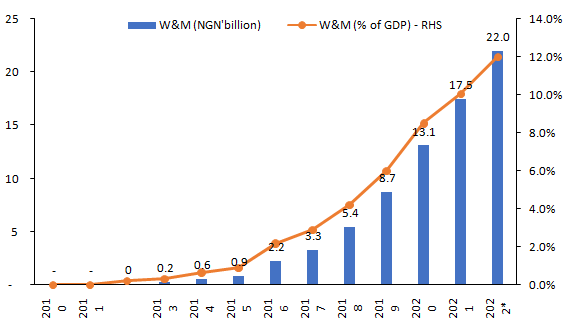

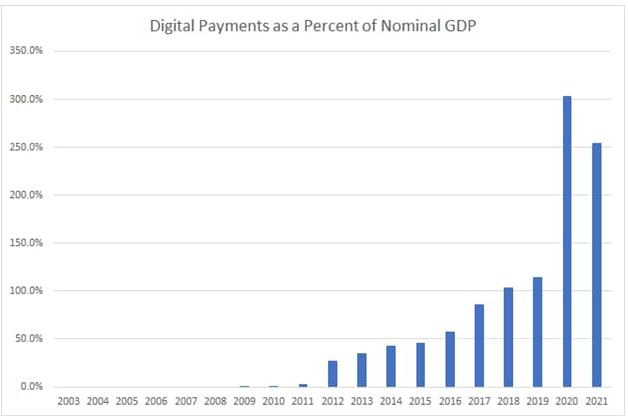

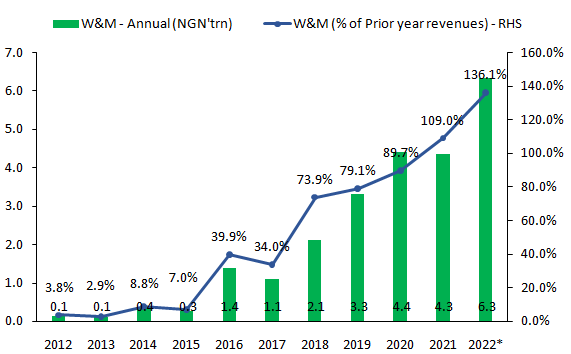

Since 2015, Nigeria’s Federal Government has extensively relied on advances from the CBN to finance fiscal deficits in excess of approved budget amounts. Cumulatively, these advances sum up to N22.1trillion at the end of August 2022 (12 percent of GDP) and were essentially financed by the CBN expanding the monetary base (or simply put: printing money). For context, total FGN domestic debt rose from N8.8trillion in 2015 to N20trillion at the end of June 2022, while the W&M figure went from under NGN1trillion in 2015 to N20trillion in the space of six years, faster than the rate of legislated borrowing plans. Beyond the scale of the increase, the W&M advances present legal problems as these amounts are in breach of provisions within the CBN 2007 Act which not only set a ceiling on W&M borrowings at no more than 5 percent of prior year revenues but also stipulated that new advances cannot be granted without repayment of prior year advances. In addition, the position runs contrary to ECOWAS convergence criteria which sets a 10 percent of prior year revenues as the ceiling for central bank finances to the government within the sub-region.

Figure 1: Cumulative Ways and Means Balances

Source: CBN, NBS

In seeking to convert these W&M advances to FGN debt, the Buhari administration is perhaps signaling a desire to draw the line on the practice as its tenure winds down.

A short history of Ways & Means

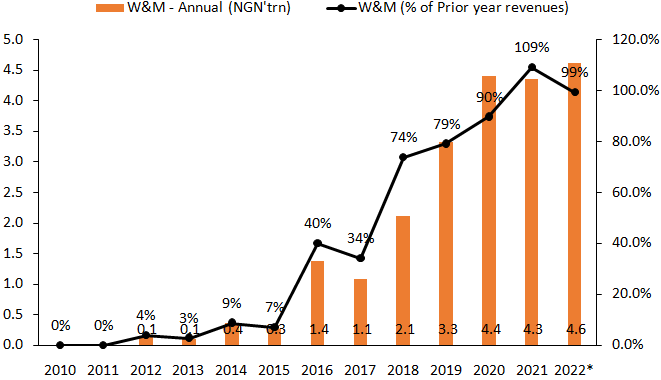

Historically, W&M or to use the proper economics term, unrestrained central bank deficit financing has been observed in two major episodes of Nigeria’s history looking at CBN data going back to independence in 1960. The first episode was during the 1993-2000 era when CBN advances to the FGN in excess of budgeted amounts went from zero to a peak of N34billion in 1996. As a share of fiscal revenues, the amount peaked at 5.4 percent in 1996 and generally stayed within range. In 2007, as part of the CBN 2007 Act, the Obasanjo administration which wound down the Abacha era W&M facilities reduced the limit to 5 percent.

However, the 2015-2022 era is unprecedented in Nigerian history as W&M as a ratio of prior-year revenues hit 109% in 2021. Essentially the CBN generated more money than the FGN in the prior year though 2020 revenues were undoubtedly hurt by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 2: Annual Ways & Means borrowings

Source: CBN, Budget Office.

So, what happened in the last six years?

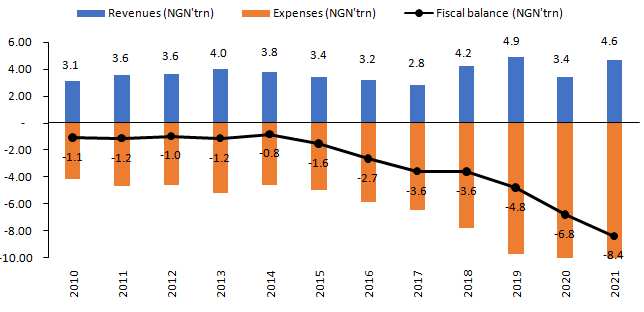

The concurrent collapse in oil prices and Nigeria’s oil production in 2016 cascaded into a drop in FGN receipts. Following the dip in oil prices, Nigeria’s oil exports dropped from an average of USD85billion in 2010-2014 period to USD42billion in 2015 and USD32billion in 2016. In the face of the collapse, the FGN responded by maintaining expenditure levels in a bid to shift the economy out of recession. This bold gamble required financial assistance from the CBN which printed over N1.4trillion in 2016 to sort out the FGN. Rather than being a one-off, the practice soon became embedded as the finance ministry saw a solution to ramping up expenditure levels despite the exit from recession in 2017 and accessible Eurobond financing over the period.

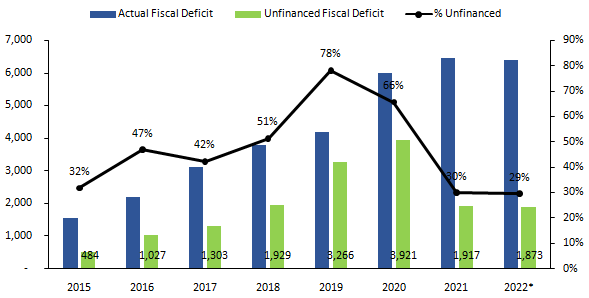

Figure 3: Nigeria Fiscal Accounts.

Source: CBN

When governments run fiscal deficits, they usually borrow to cover the revenue shortfalls to their spending plans. These borrowings have to be approved by the National Assembly as part of the appropriation bill and can be either domestic (via FGN bonds and treasury bills) or foreign via Eurobonds or concessionary loans from bilateral(such as from China, France, India etc.) and multilateral agencies (such as the World Bank, IMF). Once the budget is passed, borrowings have a hard ceiling and when the actual deficit exceeds the projected deficit, the is no legal recourse for the Debt Management Office (DMO) to borrow in excess of the budgeted borrowing amount. To address this, the CBN as the banker to the FG can provide over-draft facilities to meet temporary differences between budget and actual revenues arising from timing differences. For instance, corporate taxes tend to be paid over the third quarter but the government has running costs which need some financing. As such the CBN provides over-draft facilities on these budget accounts. The real problem with W&M is when the actual deficit exceeds the budget deficit by a sizable difference. Given the testy process and haste required in financing these hitherto over-budgeted deficits, the Buhari government found it expedient to simply tap the CBN to extend short-term financing to cover its shortfalls.

So, what is the big deal about Ways & Means?

Unrestrained central bank financing of budget deficits is generally problematic given that it essentially amounts to printing money which raises the money supply. When this exceeds the absorptive capacity of an economy i.e. relative to the amount of goods and services available, economists posit that the excess money supply balances directly fuel inflation. This has its origins in the so-called quantity theory of money by Irving Fisher.

Indeed, over the last six years, the broadest monetary supply aggregate has risen more than double to N49.4trillion (27 percent of, GDP) from N21.6trillion (23 percent of GDP) in 2015. Core inflation, a measure of inflation which excludes food and petrol prices, which tend to be volatile, has averaged 11.8 percent, up from single digit average of 9.5 percent in the preceding eight years. Though not causal, these directional movements suggest links between the expansion in money supply and inflation.

Perhaps one area where the expansion in money supply is likely to pose greater problems is in currency management. Excess money supply balances above an economy’s absorptive capacity are likely to flow outwards towards the purchase of external goods. Given the external account pressures over the last six to seven years, occasioned by the collapse in crude oil prices, the resilience in dollar demand in the face of fairly large currency devaluations hints at an outsized role of the CBN ways and means operation.

What are the implications of this securitization on Nigeria’s economy?

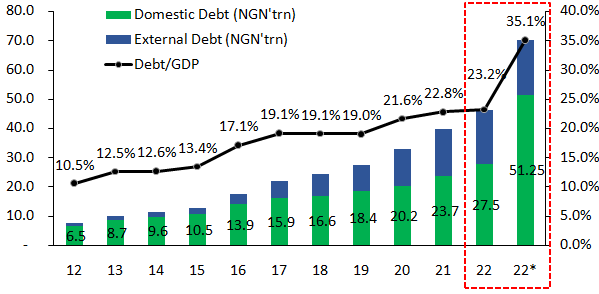

Firstly, Nigeria’s debt metrics are about to change, as the securitization raises debt-GDP ratio to 35 percent of GDP from 23.7 percent at the end of June. While this remains below the recently raised parliamentary ceiling of 40 percent, this development robs Nigeria of the low debt narrative that has appealed to international investors in recent years

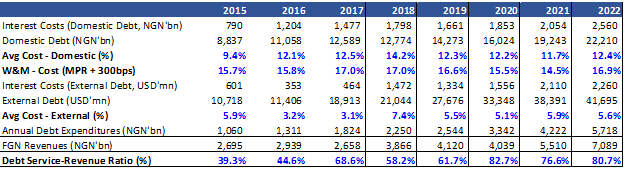

Secondly, in terms of debt service costs, the 9% rate (which favourably compares with the current 13.3% weighted average cost of debt on Nigeria’s NGN20.9trillion domestic debt) implies incremental debt service costs of N1.8trillion. For context in the FGN debt service costs in the 2022 budget are set at N3.9trillion. Assuming fiscal revenues continue to tail the N5-6trillion level observed in the last five years, the increase pushes debt-service revenue ratio higher (Jan-July 2022: 84 percent) which presents challenges for future governments.

Thirdly, from a principal repayment perspective, the securitization will potentially add around N500billion in principal repayments (assuming no repayment moratorium and equal amortization) as the FGN is unlikely to fathom having a bullet principal repayment N20trillion in the year 2062. More likely the repayments will be spread over the course of 40years.

From a structural perspective, the action creates some breathing space for the CBN to adopt a more reasonable Naira liquidity management operation. Presently, while printing huge sums of money to plug fiscal deficits, the CBN engages in countercyclical contractionary monetary policy to limit the inflationary blowback of excessive growth in money supply. Unlike in conventional monetary policy when the CBN would sell securities at an interest rate that incentivizes banks to purchase these securities, the CBN engages in a low-cost, mopping-up operation via the use of cash reserve ratio (CRR) debits which costs nothing and more recently the issuance of Special Bills (SPEBs) which are at a yield of 0.5%. Assuming the Buhari government calls time on Ways &Means borrowings, the CBN no longer needs to restrict activity within the banking system as it now has an asset which pays interest and at decent level. Essentially, monetary policy can return to a more conventional path.

How do we prevent another episode of Ways & Means explosion in the future?

Unfinanced fiscal deficits are a function of either poor fiscal budget forecasting, if one assumes that the deviations are naïve mistakes or deliberate fiscal indiscipline. Given the persistently rising pattern of Ways &Means advances under the Buhari administration, one cannot rule out the latter. Combined with the annual ritual of announcing new tax levers to unlock mythical revenue numbers, it is not uncontroversial to say that the finance czars adopted a kamikaze approach to fiscal affairs.

To prevent future abuses, parliamentary oversight must include explicit provisions that prevent the passage of new appropriations bills without explicit borrowing provisions to pay down outstanding unfinanced fiscal deficits. To improve coverage, the finance minister should be made to prepare supplementary appropriation bills in the event of the existence of Ways & Means balances in excess of the statutory 5 per cent limit. Lastly, CBN governors must be made to sign annual declarations that they have not breached Ways & Means. And there should clear and serious consequences, including criminal prosecution and jail sentences, when it is proven that these declarations are false.

*Thompson is an economist with specialization in monetary policy

[1]Source: DMO. Total FGN debt is split across domestic debt (NGN20.9trillion) and external debt (USD40.1billion or NGN14.7trillion).

- Details

- Policy Insight

By Samuel Ajayi and Maryam Ibrahim | In the last 12 months, there have been some significant shifts in the size and structure of the revenues shared to the three tiers of government and other statutory recipients by the Federation Accounts Allocation Committee (FAAC).

- Details

- Policy Insight

By Adebayo Ahmed | The current cash crunch is the dominant issue in Nigeria today. To go about their daily lives, many people all over the country are spending countless hours on never-ending queues trying to get some money, which they presumably own. With frustration building, as a result of the cash crunch as well as other issues such as the fuel crisis, the obvious question is: “what is the way forward”? Should Nigeria continue as is, hoping that people manage the suffering for real or perceived future benefits? Or do we need a course correction before the lid gets blown off completely and we find ourselves with a severe economic contraction or worse?

The currency change policy

The cash crunch can be linked directly to the policy effort of the Central Bank of Nigeria(CBN). In October 2022, the CBN announced plans to change the currency, replacing the soon-to-be-decommissioned N200, N500, and N1000 notes with new versions. Reasons given for the change ranged from fighting counterfeiting, kidnapping, corruption, money laundering and other forms of illicit financial flows. Additionally, the policy has been touted by some advocates outside of the apex bank as a tool for stopping or limiting vote buying in the upcoming elections. Although there were indirect suggestions that efforts would be made to promote digital transactions over cash going forward, there was no new and explicit statement on cash restrictions beyond what was already in place via the cashless policy when the currency change was announced last October.

Most of the reasons given for the new policy are valid. As pointed out by the CBN, the currency notes being changed had not been redesigned in over 20 years. Improving transparency through increased digital transactions has also been a longer-term goal of the CBN, and a good one too. However, some of the reasons given were on suspicious economic grounds, such as too much cash being outside the banking system. It can be safely assumed that the point of cash is for it to be in circulation and not sitting in bank vaults and that reducing money supply in general would be part of its regular monetary policy operations. Regardless, a currency change was not expected to lead to a significant cash crisis.

However, as has become clear, the actual policy being implemented was not simply a change of the currency but a sort of “demonetisation” process. The expectation of the CBN was that cash being deposited would not be withdrawn one-for-one, but that customers would adopt other non-cash systems. This cash crisis has however exposed some of the weaknesses in the policy approach.

The policy challenge and why

The first key weakness exposed is that the CBN appears to have grossly underestimated the economy’s actual cash needs. By the economy here we mean just regular people who need cash for their livelihoods on a daily basis. As most economists are aware, Nigeria is a sort of dual economy with a significant informal sector. This is important because informality and cash use tend to go hand-in-hand. How large is the informal sector? A report by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) estimated that informal activities accounted for 41.43% of all activities, or of GDP, in 2015 (https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/download/403). The World Bank similarly suggested that up to 80.4% of employment in Nigeria in 2021 was in the informal sector (https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/publication/informal-economy). The summary is that informality in Nigeria is a norm and hence the financial needs of the informal sector, notably cash, would be just as significant.

Surveys on use of cash in the day-to-day lives of ordinary Nigerians corroborate those accounts. From the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys(MICS) published by the NBS last year, only 35.4% of women and 47.2% of men aged 15 - 49 as at 2021 had bank accounts or any other similar set up in any financial institution. The implication of this is that the non-account-holding population use/need cash to survive on a day-to-day basis. In fact, in states such as Bauchi, Jigawa, and Kebbi, less than 8% of women had bank accounts. The most popular reason given was that they did not have a stable income, and apparently they were using cash daily for survival.

The use of cash is not limited to just the lower income segment though. Another survey in 2021 by Enhancing Financial Innovation in Africa (EFINA) asked a subset of adults if they had used cash for payments in the last year. 100% said they had. Only 24% said they had used digital means for making payments in the preceding year. Similarly, 86% said they had received some income in cash in the preceding year. Only 13% said they had received income by digital means. In summary, almost all available information pointed to cash being ubiquitous in the daily life of Nigerians. The failure by the CBN to foresee this necessary cash demand means that it probably underestimated how much demand there would be for the new currency notes.

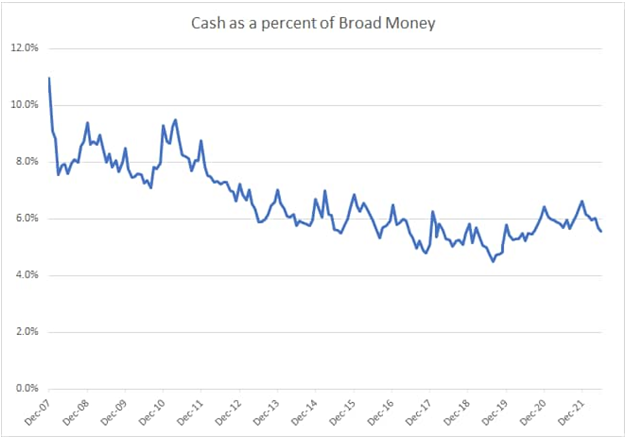

Fig 1: Cash outside depository corporations as a percent of all broad money Source: CBN Quarterly Statistical Bulletin

Fig 2: Digital Payments as a Percent of Nominal GDP Source: CBN Quarterly Statistical Bulletin, CBN Statistical Database, Author’s Calculations

The ubiquity of cash does not however mean that Nigeria has not made progress in the move towards a cashless economy. Indeed, due to technological innovations that have put mobile phones in almost every hand and a previously favourable policy environment by the CBN, Nigeria has made tremendous progress in digital finance as evidenced by the continued growth in digital transactions (Fig 2). Nigerian entrepreneurs continue to build innovative products that use the improved digital connectivity to provide financial services to more and more people. On a monetary policy front, cash has slowly become a smaller share of all broad money. As is clear in Fig 1, The percent of cash to all money has fallen from 11% in 2007 to about 5.6% as at June 2022. The percent of cash to GDP has similarly fallen from over 2% of GDP in 2007 to 1.67% as at the end of 2021. For context, a study by the IMF suggested that countries such as the UK, the US, China, and Japan had about 3.5%, 7.5%, 9%, and 20% currency in circulation relative to their GDP (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/03/01/Cash-Use-Across-Countries-and-the-Demand-for-Central-Bank-Digital-Currency-46617). By all accounts, Nigeria does not appear to have a cash problem and was already moving in the digital direction even before the currency change. The problem the policy was trying to solve was not really there.

The second key weakness identified is one of unforeseen capacity constraints. On the one hand, and if unofficial information is to be believed, the Nigerian Security Printing and Minting Company Limited - the government owned corporation responsible for printing currency locally - only had the capacity to print about N200billion by the end of January 2023. A long way short of the N2.73 trillion cash in circulation as at September 2022. You do not need to solve too much mathematics here to see why there is a cash crunch. The CBN, via the NSPM PLC, just does not have the capacity to exchange all old notes for new notes even if they wanted to. The attempt by what must have been an enormous number of people looking to quickly migrate to digital platforms also appears to have overwhelmed some of the key financial institutions like NIBSS who must have had very little time to build up capacity. If the Minister of Finance was unaware of the policy in advance, as she told legislators last year, then it is fair to say the banks and associated financial institutions were also unaware.

The consequence of CBN’s failure to properly estimate cash demand, the lack of capacity to actually print new Naira notes, and the unpreparedness of the banks and associated financial institutions to handle the extra demand means that many people in Nigeria are stuck. Long queues at the ATMs that have cash to dispense. Little cash over the counter at the banks. More failures in digital transactions. As with most economic problems in Nigeria, the poor, especially women, are left bearing the short end of the stick. As is clear above, women are much more excluded from the financial systems compared to men. As we also learned during the COVID-19 pandemic, women are much more vulnerable to extra demands on their time due to cultural expectations on activities in the home.

As with other situations involving scarcity of a key commodity, some people exploit the situation for the own benefits. Various examples have been reported in the news already from bank managers looking to give cash selectively to their preferred clients and POS agent looking to make a quick extra buck from desperate customers with few other options. These are all symptoms of the cash scarcity, rather than the cause. We see these practices not only with cash but with FX and fuel. As with other instances, we can spend time and effort sending the secret police and EFCC to harass people but that will be equivalent to taking a pain killer when what you really have is malaria.

Potential outcomes with the status quo

The CBN obviously cannot print enough new currency to meet all the legitimate demand, and the financial system is struggling to cope with the increased demand for its digital services. So, what happens if we retain the status quo with continued cash scarcity? From an economic perspective, that will be tantamount to a sharp reduction in money supply which will most likely be associated with a sharp reduction in economic activity, especially in the informal sector. Sharp reductions in economic activity are typically associated with protests and in some circumstances social unrest. Just as during the COVID-19 pandemic, the how and where these will occur will always be a surprise but they tend to happen. There are some intimations of this already, from banking halls to the streets.

A second consequence of continuing with the status quo is that trust in the banking system will be eroded even more, ironically likely setting back the cashless policy. The banks, and to a large extent the whole financial system, run on trust. Trust that when you put your money in a bank you expect to get it back when you need it. The likely outcome of this cash crisis is that people seek more financial options outside the banking system to limit the risk to their livelihoods in the event something similar happens again.

Policy options going forward

Although some of the objectives of the currency change policy are laudable, the costs to the economy, especially the poor and most vulnerable, are too high to ignore. Very few people can argue against taking actions to tackle kidnappers’ use of cash or to limit the use of cash to influence elections. However, as with every policy, the benefits have to be weighed against the costs. When this cash crisis is combined with the fuel crisis, the already high food inflation, and a competitive election season, then the risk of a self-inflicted recession and social unrest is too high to ignore. It will be tantamount to turning up the heat under a pressure cooker that is already bursting at the seams.

One option will be to increase supply of the new notes by printing abroad. Aside other complications, this will take time and thus will not address the short-term crunch. On the basis of this, the only credible path to reducing the pressure and limiting the economic consequences with the unfortunate effect on the lives and livelihoods of the poorest, is to extend the timeline for the currency change. This should be done with a concerted effort to return some of the old notes into circulation to immediately ease the cash crunch.

If this is done with a new timeline that is far enough that most people do not fear the immediate risk of accepting the old notes, and is communicated clearly and transparently by all parties, then the cash crisis will end. Guaranteed, the reputational damage to the CBN from having to walk back on the policy will be difficult to reverse, but there is no cost-free path now. We can only choose the least costly option. And in doing that, the ego of the central bank should weigh far less than the economic, social and political costs to the entire system.

- Details

- Policy Insight

By Adebayo Ahmed | Since President Donald Trump was declared the winner of the 2024 election in the US, most of the world started holding its breath, with the level of economic uncertainty inching up multiple notches.

- Details

- Policy Insight

By Wale Thompson | Last week, both chambers of Nigeria's parliament approved President Muhammadu Buhari's December request to convert longstanding overdraft facilities obtained from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) - amounting to N23.7 trillion - into government bonds, the so-called "securitization." This move draws a line on a longstanding issue that had raised concerns about the management of Nigeria’s fiscal policy and economy over the past eight years, and the approval will now go for ratification by President Buhari, with less than a month to the end of his tenure. For the sake of context, it should be noted that the so-called 'Ways and Means' (W&M) provisions allow the CBN to provide short-term financing to the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN), with an annual ceiling set at no more than 5% of the prior year's fiscal revenues, on the condition that these loans are repaid before new advances are extended by the CBN to the FGN. However, over the last eight years, the outstanding W&M advances skyrocketed from N790 billion in May 2015 to N23.7 trillion by the end of October 2022. The cumulative figure for W&M advances over the last eight years is equivalent to 77% of the trailing fiscal revenues between 2014 and 2021. Moreover, the ratio of annual W&M drawdowns to prior year revenues averaged 71% during this period, indicating that both the CBN and the Finance Ministry breached the 5% limit prescribed by the law.

Figure 1: Ways and Means

Source: CBN, Budget Office; * January to October

How does this securitization impact Nigeria’s debt metrics?

Firstly, the incorporation of the securitized W&M advances into Nigeria’s official debt data implies a jump in aggregate public debt (inclusive of state government loans of N7.3trillion) from N46.3trillion in December 2022 to N70trillion. This means that Nigeria’s total public debt is now around 35% of GDP, up from the 23% of GDP at the end of 2022 and just under the 40% limit per the medium-term debt strategy approved by the National Assembly in 2021. While this level implies that Nigeria can no longer be classified as low-debt country, Nigeria’s debt-GDP metric remains below the 50-55% average observed across emerging and developing countries. To put this in context, Ghana’s debt-GDP ratio was running at 93.5%. Indeed, in its 2022 Nigeria Article IV report published in February this year, the IMF, which incorporated W&M loans in its definition of Nigeria’s debt obligations for its Debt Sustainability Analysis (DSA), classifies Nigeria as having a "moderate" overall risk of sovereign stress. In justifying this position, the IMF which estimated Nigeria’s debt-GDP ratio at 37%, noted that external debt burdens remained low (9% of GDP) plus a large share (over 85%) of domestic and external debt is of medium to long term maturities. On this note, the Ways and Means (W&M) securitization does not radically alter these features as the new debt is of long-term nature (40-years) and in local currency.

Figure 2: Debt/GDP Data - Nigeria

Source: DMO; *January to October

While the securitization of W&M loans suggests limited damage to Nigeria's overall debt capacity, the focus is often on debt service, as highlighted by the president of the African Development Bank, Mr. Akinwunmi Adesina, who famously stated that "we cannot eat GDP." On this front, the securitized W&M loans will arrive on the public debt balance sheet at a single-digit rate of 9%, which is lower than the expensive cost of the Ways and Means (W&M) financing, currently set at the Monetary Policy Rate (MPR) plus 300 basis points. The current MPR rate is 18%, which implies that the cost of W&M financing is at an interest rate of 21%, making it more expensive than the cost of regular Naira debt issuances. Therefore, it is clear that there will be significant cost savings from the securitization of W&M loans, which will have knock-on effects on debt service costs. At 9%, the annual costs of the outstanding W&M loans will drop by more than half to N2.1 trillion, compared to N4.9 trillion if we use the current cost of 21%.

Table 1: Debt Service Costs

Source: CBN, DMO, Budget Office, Author’s computation

How does the W&M impact the conduct of monetary policy now?

It is important to note that the W&M loans in Nigeria were largely financed through an expansion in money supply, or more simply, printing money. The broadest measure of money supply in Nigeria, M3, was N21.8 trillion in May 2015 but surged to N52.1 trillion at the end of 2022, driven by significant growth in lending to the government from N2 trillion to N27 trillion among other factors. Historically, there was a bias against central bank financing of budget deficits, but economists now believe that some level of central bank financing is acceptable within reasonable limits. The key is to ensure that these loans are consistent with the growth rate of money supply in tandem with economic activity. There has been a trend towards the use of legislative limits, such as the 5% of prior year revenues ceiling for FGN borrowings from the CBN as stipulated in the CBN Act 2007. This trend has accelerated globally since the 2008 financial crisis and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic, as advanced economies responded to weak economies with large asset purchase programmes financed through a broad-based expansion in money supply. However, in Nigeria, the rapid expansion in money supply over the last eight years, which is unprecedented in recent years, is tied to the CBN financing of FGN deficits. Not surprisingly, Nigeria’s core inflation, which excludes volatile food and fuel prices, has jumped from single digit levels in 2013-2015 to 19% in March 2022.

Naturally, some might ask will this securitization lead to increased inflation over the near to medium term. Given that the securitization seeks to legalise what has already happened (i.e. CBN to FGN loans) then discussions about inflation are moot as the deed has already been done. Essentially, the W&M securitization is not a fresh request for CBN to lend money to the FGN, rather it’s the FGN providing legal form to monies that have already been borrowed from the CBN and disbursed into the economy over the last eight years. Whatever inflation arising from the expansion in money supply is already reflected in the ‘system’. That said, the securitization now leaves room for the CBN to return to the business of conventional monetary policy as it no longer has to grapple with the implications of increasing money supply via lending to the FGN on the one hand and sterilizing the increased liquidity via ad-hoc cash reserve ratio debits on the other. With these loans out of the way, CBN is expected to return to orthodox liquidity management via credible market operations and move away from the current crude quantitative zero-cost approach to liquidity management.

How can Nigeria prevent future breaches of the W&M provisions in the CBN Act?

To answer this question, it must first be acknowledged that the root driver of CBN to FGN loans is the existence of large unfinanced fiscal deficits—that is a budget deficit to which there was no provision in the approved annual budget. Let’s assume that the Nigerian government planned to spend N15trillion but projected to raise revenues of N10trillion resulting in a N5trillion deficit. Usually, the annual budget would include a borrowing or financing provision for the N5trillion shortfall. Now assume that annual revenues came in at N7trillion relative to the N10trillion target and actual spending was at N15 trillion in line with the target, the actual deficit is now N8trillion comprising a budgeted deficit of N5trillion and an unbudgeted deficit of N3trillion. Who funds the shortfall deficit? Ideally, the Executive via the Finance Ministry should prepare a supplementary budget to cover the N3trillion-gap, but owing to timing issues and likely apprehension over the potential fallout from debating a new debt-ridden supplementary budget may mean that the need to approach the National Assembly for new borrowings is often swept under the carpet. As the FGN’s banker and with the instrumentality of the Treasury Single Account (TSA) the CBN has an implicit obligation to provide a short-term facility to cover unfinanced deficits. The real issue clearly is the failure of the executive to approach the legislature with a supplementary budget. A related issue to this is how realistic the annual budgets are. There is a strong argument that the Nigerian budgets are deliberately crafted to ensure easy acceptance by the populace at the expense of a more realistic assessment of revenue profiles. In essence, the unfinanced deficit appearance is not some naïve error of forecasting but one that was set in stone the moment the budget was prepared without any sense of realism.

This is the story of Nigeria over the 2015-2022 period when following the collapse in oil prices in the 2014-17 period and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, fiscal revenues cratered, which should have resulted in either downward adjustments in spending or increased borrowings. As governments are often reluctant to respond to dramatic negative changes in fiscal revenues given political considerations, borrowings are an easier decision to make to finance revenue shortfalls. This is more so in developing economies where the risk of social disorder is high. Add the operationalisation of the TSA which created an easy avenue for requests of overdraft facilities by the FGN to the CBN.

Figure 3: Financed and Unfinanced Fiscal Deficits

Source: Budget Office, Authors Computation *January-November

Fixing this requires inclusion of legal provisions which open the possibility of criminal prosecution with jail terms for finance ministers and CBN governors who violate these provisions. As a line of oversight, the National Assembly can impose an annual requirement for the heads of Nigeria’s fiscal and monetary policy teams to declare the existence or otherwise of W&M loans in excess of statutory limit with criminal prosecutions where infractions are observed. This does two things. Firstly, it imposes an obligation on finance ministers to prepare more realistic budgets or where dramatic changes occur to budget estimates, to submit supplementary budgets to clear out any unfinanced fiscal deficit. Secondly, this also curtails the appetite of future CBN governors to ingratiate themselves to the FGN via the provision of unrestrained financing in breach of the CBN Act. Lastly, parliament can introduce a provision wherein the existence of above target fiscal deficits beyond a certain threshold in two consecutive years should be grounds for the dismissal of the Head of the Budget Office. The Budget Office is a specialised sub-unit of the Finance Ministry which should be staffed with technical experts in fiscal projections. Unfinanced fiscal deficits are by and large a symptom of poor budgeting processes and fixing these issues at the source can greatly reduce the probability of future breaches in W&M legal provisions.

Conclusion

It is very important for Nigeria to draw a line on the entire episode as unrestrained CBN financing of fiscal deficits can create moral hazard problems in that future Nigerian governments, rather than embark on structural reform to increase fiscal revenues will merely engage in excessive spending and borrowings. This perception of an endless pool of domestic financing more often than not makes governments more financially reckless with little regard for fiscal discipline and such reckless disposition will ultimately lead to inflationary pressures and long-term macroeconomic instability. Moreso as we have seen in the Nigerian experience, it limits the ability of the central bank to carry out credible monetary policy as its core stabilisation and market-signalling tools lose efficacy in the eyes of financial markets.

*Thompson is an economist with specialisation in monetary policy.