Policy Platform

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Adebayo Ahmed | The question of food is one that is now on everybody’s lips in Nigeria. The food situation has worsened significantly in the last year partly driven by efforts to turn the economy around in terms of petrol subsidy removal and the foreign exchange market reform. The situation seems dire with increasing cases of violence and civil unrest associated with hunger and with fears that if the situation is not well handled, the country could be headed to the same type of civil unrest witnessed with the COVID19 palliatives in 2020 or worse.

Fig 1: Prevalence of moderate to severe food insecurity. Source: FAOStat

Although the food issue is, or at least should be, top of the agenda right now, the challenge of food security is not really new to Nigeria. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), about 34.7% of the population was experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity in the 2014 to 2016 reference period. By any standard, 34.7% was already high. However, the situation worsened almost continuously each year so much so that by the 2020-2022 reference period, an estimated 69.7% of the population was experiencing moderate to severe food insecurity, with 21.3% in the severe category. This worsening trend is backed up by data by the Cadre Harmonise which estimates that 31.5 million households in 26 states plus the FCT are expected to be in crisis in the “lean” season between June and August of 2024. This is up from the 26.5 million people estimated to have been in crisis for the same period in 2023. The total number nationwide is likely higher given that the Cadre Harmonise looks at only 26 states and the FCT. Importantly, the distribution of hunger is nationwide with almost no state spared. The combination of worsening hunger and national spread means that Nigeria is near the top of countries with hunger problems. For example, Nigeria ranks 109th out of 125 countries on the Global Hunger Index1 and 107th out of 113 countries on the Global Food Security Index2.

The rising hunger is not without consequences. According to the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey, an estimated 37% of Nigerian children under five years of age are stunted, meaning they do not develop to their full potential. According to UNICEF3, an estimated two million children already suffer from “severe and acute malnutrition”. This likely contributes to our under-five mortality rates of 107.2 per 1000 live births, the third highest of all countries compiled according to data from the World Bank4. Given our population relative to others, it implies that globally, a large number of children who die before the age of five from reasons, including hunger, are from Nigeria. Although the current situation seems more dire than normal, it is important to accept that this hunger crisis is not a one-off problem.t is a problem that has worsened continuously over a long period of time.

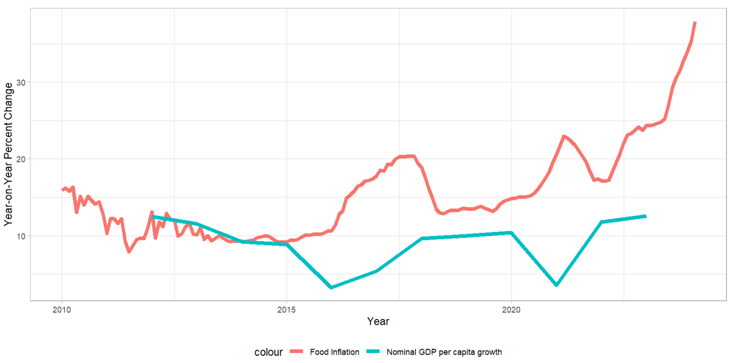

Fig 2: Food Inflation and Nominal GDP per capita growth. Source: NBS and Author’s calculations

Causes of Food Security Crisis

The causes of the food security crisis are actually very simple and can be thought of from two perspectives. The first being that food prices have risen systematically faster than household incomes. As is clear from Figure 2 above, average incomes have grown significantly slower than food prices since 2015. This means households have been getting continuously squeezed and food has become increasingly unaffordable. The measure of average income used here is simply average nominal GDP per capita but if you incorporate income inequality then it is likely you will see a tighter squeeze at the lower end of the income ladder. Things have gotten worse in the last year but it should be clear to all that the situation has been brewing for almost a decade.

The causes of rising food prices have been rehashed over and over again but they are worth repeating regardless. Monetary policy has been loose, leading to the classic demand push inflation of more money chasing fewer goods. Trade policy has been restrictive, leading to supply disruptions which have put upward pressure on food prices. Interstate logistics continues to be challenging, leading to a wide variation in prices across the country and household paying more than they could have been paying if logistics were better. Farming techniques continue to be “traditional” and rain-driven, leading to mostly low agricultural yields. Climate change has made it more difficult for farmers to produce reliably. The security situation has continued to worsen especially in key agricultural areas, limiting access to usually productive farmlands. And so on.

The last point highlights the second perspective for the cause of the worsening food crisis: livelihoods i.e. whatever people do to earn a living. To be clear, livelihoods here does not refer only to those of farmers, but to barbers and street vendors, and bankers, and so. And as can be seen from the 2023 Cadre Harmonise which estimated the distribution of food insecurity by state, there are more people under hunger stress in Lagos State than in any other state. The majority of people in Lagos are not employed in the agriculture sector. Food prices may rise fast enough that even people whose livelihoods are not disrupted can become food insecure. But the other perspective is that people’s livelihoods may be disrupted so that even with the same food prices, they no longer have the capacity to afford to keep themselves out of food insecurity.

The disruption to livelihoods in rural communities is a good place to start in thinking about this perspective. The deteriorating security situation and climate change are both combining to make earning a livelihood from agriculture increasingly difficult. Farmers in many communities cannot access lands because of terrorists, bandits, kidnappers, and so on. In other places where they can access land, climate change is leading to more irregular weather, making their production more volatile thus impacting their livelihoods. On the urban front, the absence of decent job growth and almost consistent economic shocks, from the 2015 oil price crash to COVID19, to recurring foreign exchange crises, have put a similar dent on livelihoods and income growth. Both factors mean that almost everyone is now feeling the squeeze, though the poor (who are in the majority) are disproportionately impacted.

The Path Out of the Crisis

Given that the crisis is seemingly largely about affordability, the path out of the crisis likely involves tackling affordability both immediately and in the long-term. In terms of immediate responses, the key is to on the one hand get money directly into the pockets of households, and on the other hand take action to put downward pressure on food prices. The government, at the federal, state, and local levels, should have a lot more money flowing to their coffers given that petrol subsidies were removed, and that the weakening of the national currency should mean more Naira from crude oil revenues. Re-directing some of this windfall directly into the pockets of Nigerians would automatically improve their capacity to afford food and will do so immediately. There has been talk of a cash transfer programme by the Ministry of Finance with 15 million households targeted. It is however time for more action and less talk. And of course, states and local government areas that are also benefitting from the windfall should not be let off the hook.

Some may argue that there is a risk of putting even more pressure on inflation if more money is funneled directly to households. This does not have to be the case in practice. If the social transfers are funded by already existing revenue and not by an increase in money supply through increased domestic debt or central bank financing, then the impact on inflation should be minimal.

And of course, putting money into the pockets of households however has to go hand in hand with other attempts to increase food supply and put downward pressure on food prices. On this, there are many short-term options on the table. Can we do anything to immediately reduce the portion of food prices that is due to logistical challenges and corruption on the highways? Does it make sense to have a sixty to seventy percent tariff plus duty on imported wheatand rice, at a time when food prices are relatively sky-high and unaffordable?

Dealing with the currency issues, which has resulted in the Naira weakening so much that most food items in Nigeria are cheaper than in some neighbouring countries also needs to be resolved. International demand for food items from Nigeria has increased putting upward pressure on prices. A weakening Naira means that food traders would rather collect foreign currency than sell to domestic consumers. As the currency weakens further, domestic prices for tradeable food items would have to adjust which would worsen the affordability challenges. The problems on the macroeconomic front transmit to very real challenges. Stabilising things on the macroeconomic front, specifically the exchange rate, is therefore a necessary part of the immediate measure to deal with the challenge.

On a related note, it may be tempting to try to limit the impact of the exchange rate on food prices by other means such as trying to limit cross-border trade or trying to increase domestic supply to keep domestic prices lower than prices in neighbouring countries. Both temptations are likely to be unsuccessful. We have a long history of trying and failing at restricting regional trade and the only likely result of attempts to do that now would be more smuggling and more illicit and informal trade. More importantly, restricting trade today would disincentivise farmers from doing all they can to boost domestic output tomorrow and reap the rewards of demand from international markets. The same can be said for releasing food items from strategic reserves. Given the strong demand from neighbouring countries, the food items would likely simply flow there, unless maybe they are distributed directly to households.

Longer-term Solutions

Beyond the immediate term, the longer-term solutions have to revolve around reversing the trends observed in Figure 2. That is, working to ensure that average incomes grow faster than food prices.

Conventional macroeconomic management is the starting point for ensuring that food inflation does not spiral out of control like it has done in the recent past. This means having money supply that is not growing systematically too fast, and continuing to diversify exports to minimise the risk of currency crises. In the face of macroeconomic challenges, even excellent policy on all other fronts will struggle to yield the desired results.

Improving incomes and resilience of households is the second major long-term agenda. The richer the household, the more likely they will be able to cope with food price shocks. The institutionalisation of social protection will also help ensure that households have something to fall back on in the event of more serious shocks. In this context, it is important to realise that improving resilience is not just about rural farmers but also about urban poor households, or those who are at risk of falling into poverty. For urban households, this means better jobs.

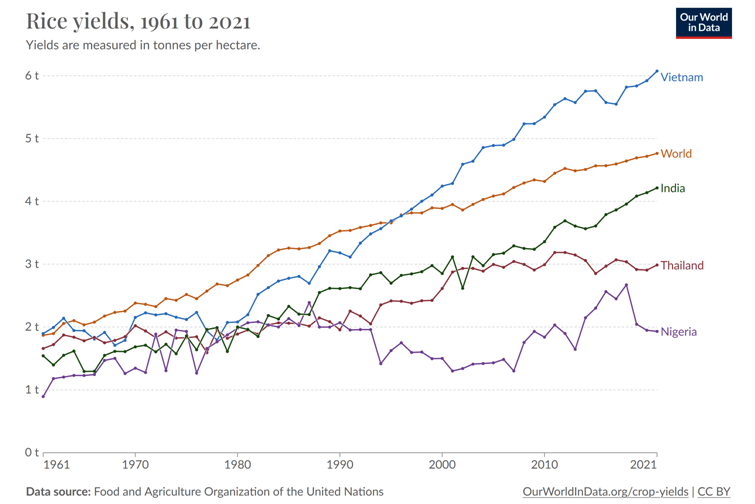

Fig 3 - a; Rice yields

Fig 3 - b: Tomato yields

Fig 3 - c: cereal yields

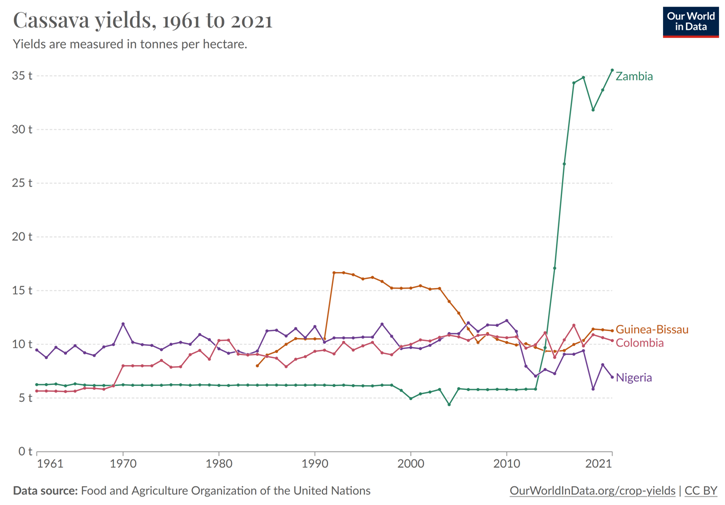

Fig 3 - d: Cassava yields

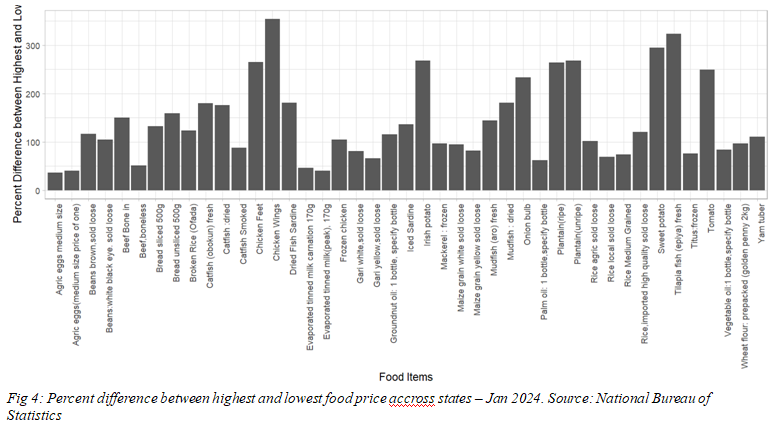

For rural agriculture-based households, this means improving productivity. Agricultural productivity is still relatively low and this is one of the foundations for domestic supply problems and high food insecurity in rural communities. As is clear from the yield on rice, tomatoes, cereals, and even cassava, yields in Nigeria are relatively very low. Improving productivity should therefore be the number-one agenda. This agenda would involve transforming farmers from subsistence farmers who farm to survive, to entrepreneurs who farm to get incomes. Turning farmers to entrepreneurs would have to involve investments in yield-improving infrastructure such as irrigation facilities, improving seedlings and seeds’ availability, improving knowledge about best practices through better extension services, improving rural security, improving resilience to climate change, improving farm-to-market infrastructure and logistics. And so on. As shown in Figure 4, the difference in prices between states is so large that just cutting logistics costs from moving food around can have a significant impact on reducing prices.

However, working to improve domestic supply and reduce costs is not enough. It is also important to build on and improve resilience to shocks in supply. This does not only involve producing more food. It involves two other factors, the first of which is storage. Storage, in the simplest of terms, is keep food when things are good to eat when things are not so good. The cyclical nature of our weather patterns in Nigeria means that we are no strangers to the importance of food storage, even if occasionally we like to throw around words like hoarders and saboteurs. Improving the quality and organisation of storage facilities should mean we are better able to cope with shocks to supply.

The second factor is trade. International trade. Leveraging international trade and building strong trade networks essentially ensures that supply is more resilient. For example, if domestic demand for a particular food item is more than current domestic supply, perhaps because the rains did not arrive on time, or because a flood damaged some output, or because the farmers techniques were not that great, international supply helps minimise the risks that the demand-supply gaps would cause scarcity or price increases. The same applies for situations when supply outstrips demand. International trade ensures that excess supply can go somewhere else and not lead to a price collapse which would also hurt livelihoods of farmers.

The second factor is trade. International trade. Leveraging international trade and building strong trade networks essentially ensures that supply is more resilient. For example, if domestic demand for a particular food item is more than current domestic supply, perhaps because the rains did not arrive on time, or because a flood damaged some output, or because the farmers techniques were not that great, international supply helps minimise the risks that the demand-supply gaps would cause scarcity or price increases. The same applies for situations when supply outstrips demand. International trade ensures that excess supply can go somewhere else and not lead to a price collapse which would also hurt livelihoods of farmers.

Getting to grips with the food security challenge is urgent but there are enough tools available to the government to turn things around and ensure that we do continue to be one of the basket cases of hunger in the world. But it will require quick action to do things today, and the foresight and the stamina to undertake more long-term, strategic and coordinated actions to remove Nigeria permanently from the hunger map. The current episode of high food prices should raise the status of the lingering food security challenges in Nigeria and propel policy makers to take immediate and longer-term decisions to sustainably reverse the trend. Food security should be seen as national security.

Photo Credit: Mansur Ibrahim

Footnotes

[1] https://www.globalhungerindex.org/nigeria.html

[2] https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/explore-countries/nigeria

[3] https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/nutrition

[4] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.DYN.MORT?most_recent_value_desc=true

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Yomi Fawehinmi | Land is a crucial resource that requires effective management by governments and various institutions to ensure equitable access and utilisation. This responsibility stems from the fundamental obligation of governments to protect the right to life, libertyand property, as espoused by the 17th-century philosopher John Locke. To achieve this objective, the government is expected to facilitate the development of an effective land administration and management system.

Such a system should enableland access, ownership, and efficient land markets, reduce tensions and conflicts about land, create clear tenure, foster economic growth, enhance local and domestic productivity and investment, improve community well-being, and enable sustainable land management and land use. Proper land administration can play a significant role in enhancing citizens' access to various opportunities and overall national growth and development.

Section 43 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria guarantees the right to property by stating that "subject to the provisions of this Constitution, every citizen of Nigeria shall have the right to acquire and own immovable property anywhere in Nigeria."

The Land Use Act of 1978 (LUA) is the principal legislation that governs land tenure in Nigeria. It regulates how land is bought, sold, managed, and used.Section 1 of the Act states that "subject to the provisions of this Act, all lands comprised in the territory of each state in the Federation are hereby vested in the governor of that state, and such land shall be held in trust and administered for the use and common benefit of all Nigerians in accordance with the provisions of this Act."

However, the Act's provisions, including the requirement for governors’ consent to land dealings, have had mixed outcomes. After 45 years of the Land Use Act, there is need for urgent reform of the law to ensure that Nigeria has a land policy that aligns with the country’s developmental goals and caters to the diverse needs of its citizens.

Prior to LUA: One Country, Two Land Tenure Systems

Before the promulgation of the Land Use Act, land tenure in northern Nigeria was influenced by two major factors: Islamic law and British rule. The Islamic influence was tied to the powers of the Emirs as communal leaders and managers of communal assets. Under British colonial rule, statutory regulation of land rights was introduced through the Lands and Native Rights Ordinance of 1910, which was later amended in 1916. The Land Tenure Law of 1962 further amended and re-enacted the 1916 Ordinance. This law declared certain lands in northern Nigeria as "native lands," and vested their management and control in the Minister (later Commissioner) for Lands and Survey, who administered such lands for the use and common benefit of the natives. Section 6 of the 1962 law empowered the minister to grant rights of occupancy to natives and required the consent and approval of the minister for the occupation and enjoyment of land rights by non-natives.

In southern Nigeria, land tenure resulted from two major influences: customary law and British rule. The customary system is based on the belief that land has spiritual value and is held in trust for the benefit of the community and future generations. Therefore, land was owned by the family or community, not by the individual. All members of the group, community, village, or family had an equal right to the land, and the chief or headman of the group held the land as a trustee for the use of the group.

It is worth noting that the Land Tenure Law of 1962 established a system of state control over land in northern Nigeria, while the customary system remained prevalent in the south. The customary system was challenged by modernisation and economic development, as individual ownership of land became more common.

The Path to the Land Use Act

In 1975, the Federal Government Anti-Inflation Task Force identified the land tenure systems as one of the causes of inflation and recommended that a decree be promulgated which would vest all land in principle in the state governments. The government rejected this recommendation.

In January 1976, the Federal Government Rent Panel also identified the land tenure system as a major hindrance to rapid economic development in the country. The panel recommended that the government should investigate the question of vesting all lands in the state. This time, the government accepted the recommendation in principle and called for further study of its practical implications.

In 1977, the Federal Government appointed the Land Use Panel to study the land tenure issue. Its terms of reference were:

- To undertake an in-depth study of the various land tenure, land use and conservation practices in the country and recommend steps to be taken to streamline them;

- To study and analyse the implications of a uniform land policy for the country;

- To examine the feasibility of a uniform land policy for the entire country, make recommendations and propose guidelines for their implementation; and

- To examine steps necessary for controlling future land use and opening and developing new lands for the needs of the government and Nigeria's growing population in bothurban and rural areas and make appropriate recommendations.

Although the panel's majority did not recommend nationalisation of land, the minority report did. The Federal Government acted on the minority report in the promulgation of the Land Use Decree, which was enacted in March 1978. The rationale for the law is set out this in the preamble: “Whereas it is in the public interest that the rights of all Nigerians to the land of Nigeria be asserted and preserved by law; and whereas it is also in the public interest that the rights of all Nigerians to use and enjoy land in Nigeria and the natural fruits thereof in sufficient quantity to enable them to provide for the sustenance of themselves and their families should be assured, protected and preserved."

In furtherance of these, the law seeks to accomplish the following objectives:

(a) To remove the bitter controversies, resulting at times in loss of lives and limbs, which land is known to be generating;

(b) To streamline and simplify the management and ownership of land in the country;

(c) To assist the citizenry, irrespective of his social status, to realise his ambition and aspiration of owning the place where he and his family will live a secure and peaceful life;

(d) To enable the government to bring under control the use to which land can be put in all parts of the country and thus facilitate planning and zoning programmes for uses.

Outside of this decree (which later became an Act), there are also different land laws in various states in Nigeria. Some of these laws include Instrument Registration Laws, agency laws and other laws related to land. For example, the Land Registration Law, 2015 empowers the governor of Lagos State to create land registry divisions in the state. Any transfer or charge in respect of property must be registered within 60 days after obtaining governor's consent, where applicable, else the transaction will be void. Also on 7th February 2022, Mr. Babajide Sanwo-Olu, governor of the state, signed the Lagos State Real Estate Regulatory Authority Bill into law. The law, which introduces significant changes to the real estate landscape in Lagos State, was enacted to protect and prevent Lagos State residents from falling prey to fraudulent real estate practitioners and to create some important obligations for stakeholders in the real estate sector.

Mixed Results of the Land Use Act

The Land Use Act has achieved some of its objectives but has also fallen short in many areas.

On the positive side, the Act has made it relatively easier for the government to acquire land for publicpurposes. Second, the law created a formal process for any Nigerian to get access to land even if they are not from the state. Third and related to the second point, the lawcreated a uniform land tenure system and land rights in Nigeria therefore reducing the arguments over rights to land. The uniformity brought some forms of predictability and simplicity in the process.

Also, the law createdpublic control and management of land in Nigeria. This potentially is a fairer management system compared to the prior case where land was held and managed by individuals, families, and communities.

While it seems that the governors have excessive powers based on this law, Section 6(1) of the law states that “the National Council of States may make regulations for the purpose of carrying this Act into effect “. The sad part is that the National Council of State has failed to do this and allowed the governors to act as they wish.

The law has noble objectives, as spelt out in the preamble quoted above. What has happened, however, is that some of the provisions of the law and their application have failed to ensure that this objective is met.

The law has some problematic provisions. However, some state governments have made the best of the situation.

Some governors have been innovative in reducing the processing times for land transactions. For example, in 2020, the Ogun State Government announced that the processing of Certificates of Occupancy (C of Os) and other title documents will not take longer than 28 days. Nasarawa State also had reforms that led to applicants requiring about 14 weeks only to be presented with CofOs. These reforms lead to faster processing and increases the speed of transactions. The laws that established the Nasarawa Geographic Information System(NAGIS)and the Abuja Geographic Information System (AGIS) have become reference points for other states to understudy and replicate.

Another innovation is how some governors and the president use their delegated powers to improve the efficiency of the process. The former Minister of Works and Housing, Mr. Babatunde Fashola, SAN, speaking at the Executive Session of the 11th Meeting of the National Council on Lands, Housing and Urban Development showed the impact of delegation in land management. He said: “We must, therefore, reform the process that governs the allocation of land and issuance of title documents such as Certificates of Occupancy. Today I can tell you that since 2017, when the president delegated his power under the Land Use Act to grant consent and issue Certificates of Occupancy to the Ministry, we have issued over 5,000 Certificates of Occupancy and granted 2,738 consents to land transactions”.

State governors are the major determining factor of the effectiveness of land administration. They influence the amount of investment in the land registry, modernisation and review of land laws and the speed and efficiency of the land approval process.

The establishment of the Kaduna State Geographic Information Service (KADGIS) is another example of how governors can impact land administration in the state. KADGIS digitised the land registry, and enabled residents to get valid land titles through systematic property registration and the recertification programme. As a result, the governor was able to sign over 50,000 certificates of occupancy between 2016 and 2022. Another example is the role of the governor in determining the cost of land transactions. In 2005, Lagos State lowered the consent fee for a transfer of land rights held for more than 10years from 16% of property value to 8%. Despite this significant reduction, this fee is still among the highest land transfer fees in the world.

While these innovations have had a significant positive effect, the Land Use Act imposes a lot of problems and constraints on the land market and thus reduces the access of Nigerians to land. In 2014, the Chairman of the Presidential Technical Committee on Land Reform (PTCLR), Prof. Peter Adeniyi, said that “The LUA is the most controversial, least understood by majority of Nigerians, very confusing and contradictory in its provisions, highly undemocratic and has woefully failed to create a right and just environment to facilitate its implementation”. He also claimed that not more than 2.5% of the land in Nigeria are registered since formal land registration began in Nigeria in 1863.

In 2016, the World Bank ranked Nigeria 185th out of 189 countries in the ease of registering property. In 2020, Nigeria had its worst ranking in this same area in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business report for that year. In registration ofproperty, Nigeria scored 29.5 out of 100. The report also stated there were 12 procedures to register land which takes about 92 days and costs 11.3% of the property value. And Nigeria’s quality of the land administration index was 8.0 out of 30. The World Bank Annual Doing Business Report (DBR) for 2018 had Nigeria’s Subnational Doing Business Report (SDBR) where each state was assessed individually. Of the four areas of reforms, (starting a business, dealing with construction permits, enforcing contracts, and registering property), the average score for all the states was 76, 69, 55 and 26 respectively (For comparison, the average score in sub-Saharan Africa for registering property was 51.)

The Land Use Act has created a distortion to the land market and reduced the law’s capacity to effectively allocate land as expected in a normal land market. One of the results is the creation of an informal market. In the informal market for land, land documents are not genuine, there is lack of clarity about the status of the land, it is difficult to hold effective transaction, the actors (not professionals) are unregulated, and the ruleof practiceis undefined. Stephen Butler (2012) estimated that more than 70% of land transactions in Nigeria are done in the informal market. This informal land market creates distortions and therefore makes land acquisition more problematic, cumbersome, and slow.

Hernando de Soto (2001) coined the term 'dead capital' to describe assets that cannot be converted to economic capital. Lack of land titles is one of the reasons for dead capital. In his book, ‘The Mystery of Capital,’ de Soto stated “the institutions that give life to capital — that allow one to secure the interests of third parties with work and assets do not exist here.” The “here” he mentions is Cairo, Egypt which lacked a mechanism to accurately record, securely hold, and easily transfer land title from one party to another.

De Soto, claimed that about 70% of all assets in Cairo can’t be identified through a ledger. Cairo can easily be replaced with most cities in Nigeria. De Soto argues that providing the world’s poor with titles for their land, homes, and unregistered businesses, would give them an estimated $9.3 trillion in assets. He claims that the land record system in the United States and the assurance of certainty of ownership is a major contributing factor in the success and prosperity of the United States and its citizens.

According to PriceWaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Nigeria “holds at least $300 billion or as much as $900 billion worth of dead capital in residential real estate and agricultural land alone. The high value real estate market segment holds between $230 billion and $750 billion of value, while the middle market carries between $60 billion and $170 billion in value”. This is lost value to the country.

De Soto claims that in the US the most important source of funds for new business is the mortgage on a small business owner’s house. So, where entrepreneurs lack secure property rights and have no ability to leverage their home as an asset to create more business opportunities, they remain poor.

One of the most important rights to land is the ability to use the land as collateral to raise capital. This mortgaging rights though permitted by the Land Use Act, however, requires the consent of the governor. Sadly, the governors have used this power to create complex administrative procedures. A 2010 IFC-sponsored study of the process for obtaining a governor’s consent to mortgage a certificate of occupancy in Lagos State found that the average time for issuance was 240 days, and that on average 16 government officials handled the application file. Arising from the above, lenders and borrowersrely on alternatives to legal mortgages, such as unregistered assignments of property which increases the risk of the transactions.

The abuse of the powers of the governors leads to exorbitant charges for land transactions and delay in granting consent. The result is the high cost of land transaction in Nigeria. The exploitation of the power of the governor to consent to all land transactions has made government officials impose different onerous conditions on applicants. Some state governments demand for development levies to be paid, using the application to reassess recent tax payments solely based on the value of the home purchased.

It is interesting to note that the Land Use Act and the Nigerian Minerals and Mining Act (2007) created a partnership between the Federal and state governments over the control of land and mineral resources in Nigeria. While the Federal Government may claim ownership of all land endowed with mineral resources, it still needs to rely on the state governments to access and acquire the land on its behalf. But how well has this relationship worked? In the Second Republic, there were allegations that the governors of the Unity Party of Nigerian (UPN) refused to allocate land to the National Party of Nigeria-controlled Federal Government for its housing estates in choice areas. In 2017, former minister Babatunde Fashola accused Lagos State Government of not allocating land for housing projects in the state. He claimed that “if there is any lack of co-operation it is on the part of the state government that has refused to acknowledge not to talk of approving the ministry’s request for land of the National Housing Programme in Lagos. The ministry is not frustrated by this lack of response and remains optimistic that a response will come from Lagos State.”

Also, contrary to the intention of the law, land has been acquired by the government and allowed to go to waste. This is most pronounced in the educational institutions where vast lands were compulsorily acquired for the schools but were never used by the schools. This has been observed at the Obafemi Awolowo University, University of Calabar, University of Jos, and the University of Uyo. In all these schools, trespassers have invaded the land and illegally erected structures on the land belonging to schools.

The law has not reduced corruption in the land sector. The prevalence of bribery in 2019 was highest in relation to police officers (33%)and land registry officers (26%).While there was an overall decrease in the prevalence of bribery in Nigeria since 2016, the prevalence of bribery has decreased in relation to almost all types of public officials, except for land registry officers, members of parliament and other officials. in 2019, speeding up a procedure was the most important reason for paying a bribe to doctors, nurses and midwives, other health workers (60 – 63%), members of parliament/elected government representatives (49%) and land registry officers (48%).

Contrary to one of its objectives, the policy has also not reduced the amount of litigation and conflicts about land and land rights. In 2013, Mr. Babatunde Fashola (who was at the time the governor of Lagos State) claimed that “of the roughly 150 processes that are served from the office of the Attorney-General weekly, at least a third, that is 50, of those processes are in respect of land or property dispute in the state.”

At the core of the failure of the LUA is the law itself. Some of the provisions do not align with democratic practice, as they have allocated too much power to the governor, and created no mechanism to drive effective implementation and oversight. This makes the case for the review of the law itself.

There are other failures which are largely the way the state governors and government have implemented the policy. Rather than implement the policy for the use and benefit of all Nigerians, most state governments see land as an opportunity to generate income for the state, restrict access to land and create an ineffective administrative system. As stated above, some governors have even frustrated the Federal Government to have access to land for development.

Attempted Reform of the Land Use Act

Late President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua identified some critical areas of national life that his administration considered of utmost priority which were dubbed the ‘seven-point agenda’. These were: Power and Energy, Transportation, Land Reforms, Security, Education, Food Security and Wealth Creation. Of these seven, President Yar’Adua believed that three of them are more important than the others and chose to focus principally on them. Three were identified: Land Reform, Niger Delta, and Power.

On 2 April 2009, he inaugurated a Presidential Technical Committee on Land Reform under the chairmanship of late Professor Akin L. Mabogunje. The Committee was “to determine individuals’ ‘possessory rights’ using best practices and most appropriate technology to determine the process of identification of locations and registration of title holdings,” as a forerunner to a National Land Commission. Professor Mabogunje had done extensive work and a bill was sent to the National Assembly. Titled the Land Use Act (Amendment) Act 2009 or the Constitution (First Amendment) Act 2009), it contained 14 amendments to the LUA. Among others, the proposed bill sought to:

- Vest ownership of land in the hands of those with customary right of ownership and enable farmers to use land as collateral for loans for commercial farming to boost food production in the country.

- Restrict the requirement of the governor ‘s consent to assignment only which will render such consent unnecessary for mortgages, subleases, and other land transfer forms to make transactions in land less cumbersome and facilitate economic development.

The government also planned:

- The establishment of specialised courts to determine the terms and timing of challenge/contestation of foreclosures.

- The computerisation of all land-related records at all levels.

- To persuade state governments to convert their housing corporations into land companies with mandate to develop new towns in the states.

- Reorganising the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) to provide mortgage insurance for affordable housing.

- The passage of foreclosure and securitisation laws.

- Sustaining the Federal Mortgage Bank of Nigeria as a secondary mortgage institution refinancing mortgage loan originators.

The uniqueness of President Yar’Adua’s approach is that rather than go through the rig our of reviewing the whole Land Use Act, he used a faster approach of using another law to drive reforms. The committee was also creative, and their solution created mechanisms that states and local government areas can use to identify, demarcate, and title the land holdings of individuals.

Regrettably, the bill was not passed by the National Assembly.

Bringing land reform back on track

The Land Use Act needs to be reviewed as matter of urgency. However, a new land reform in Nigeria will likely be resisted by those who benefit from the deficient status quo. However, it is important to note the promise made by President Bola Tinubu in his election manifesto. There, he promised that:

- “Home ownership is a source of prosperity, social stability, and individual pride. A vibrant residential construction industry is essential to a healthy modern economy.

- “In conjunction with the National Assembly and state governments, we will review and revise the Land Use Act.

- “We need to streamline and rationalise the land conveyance process. In this way, we lower costs and delays and promote more efficient use of land. This more efficient allocation will bolster the housing industry and lower costs for investors and consumers.

- “Working with state governments, we will provide credits and incentives to developers of housing projects that set aside a significant portion of their projects to affordable housing.

- “With the support of state and local governments we aim to establish and implement a new social housing policy whose objective shall be to provide pathways for the poorest Nigerians to climb onto the housing ladder.

- “We will establish a coherent federal programme to provide eligible and meritorious civil servants with federal payment guarantees for fixed-rate, long term mortgages for their homes.”

It is time for the administration to walk the talk of its manifesto, and quickly too.

We need a set of land policies that meets the World Bank standards and geared towards the following:

- Guarantee of a secure land tenure by ensuring that individuals and communities have legal recognition of their land rights, and that these rights are protected. This will reduce conflict over land issues and facilitate the land market.

- Policies that ensure the efficient use of land by promoting the productive and sustainable use of land, while minimising waste and degradation. This will help manage the environmental concerns about land.

- A land policy that increases land governance by ensuring that land management decisions are transparent, accountable, and participatory, and that they consider the needs and interests of all stakeholders, including local communities, smallholders, and marginalised groups. This will ensure fairness.

- A policy that acknowledges the legitimacy of indigenous land rights systems and enforces the rights of women to land.

- Policies that have effective supportive institutions by ensuring that land institutions are efficient, that they leverage technology and they are managed by professionals. This will help to reduce the time spent on land transactions, reduce corruption, and will promote investment in land.

- A policy that is quick and effective in resolving land conflicts. This will reduce the time and cost of land adjudication.

- A policy that creates an effective system that tracks land policy development and implementation and creates a feedback process to improve implementation and continual improvement.

To achieve these objectives, the following should be taken into consideration:

- Remove the Land Use Act from the constitution. This is to ensure that subsequent reviews won’t need to go through the onerous review processes of the constitution.

- Review and re-submit the proposals and bill by the Mabogunje Committee as a priority executive bill to the 10th National Assembly. New land reform policy should have the elements defined in the bill. This will also fasten the reform process as a lot of work has been done already.

- Redefine the role of the governors as the trustees of the land to ensure this authority go along with clear responsibility.

- Remove the consent provision from most transaction and replace it with a registration after the fact.

- Persuade the President of the Court of Appeal to designate courts for land issues and make the Court of Appeal the final arbiter on land issues. The new policy should also create time limits for all land issues.

- Undertake a comprehensive review of al the state laws about land in Nigeria. Some states have used these laws to worsen the already poor state of land administration in Nigeria.

- Create a public land records system that establishes ownership, title, and transferability of property. This record should be powered with relevant technology.

- Review the process of compulsory land acquisition to become more aligned to the current international best practices of tenure, forced evictions and the use of property for public purposes. This also includes rules around the compensation of the land using market-driven valuation methods.

- Create a form of accountability mechanism so the people can understand how well the governor is managing the trust. Section 47 of the Land Use Act deals with the exclusion of certain proceedings

“(1) This Act shall have effect notwithstanding anything to the contrary in any law or rule of law including the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999 and, without prejudice to the generality of the foregoing, no court shall have jurisdiction to inquire into- [Cap. C23.]

(a) any question concerning or pertaining to the vesting of all land in the Governor in accordance with the provisions of this Act; or

(b) any question concerning or pertaining to the right of the Governor to grant a statutory right of occupancy in accordance with the provisions of this Act; or

(c) any question concerning or pertaining to the right of a local government to grant a customary right of occupancy under this Act.

(2) No court shall have jurisdiction to inquire into any question concerning or pertaining to the amount or adequacy of any compensation paid or to be paid under this Act.”

To oust the jurisdiction of Nigerian courts is not consistent with the ideals of democracy. Also, while the law made the governor the trustees of the land, it created no form of accountability nor oversight on this trustee.

Conclusion

Nigeria's current land policy, as embodied in the Land Use Act of 1978and the various laws by state governments, have had mixed outcomes. They have failed to streamline land administration and management, and created numerous challenges and limitations that hinder equitable access and utilisation of land. As such, there is an urgent need for a new land policy that aligns with the country's developmental goals and caters to the diverse needs of Nigerians. Such a policy should be guided by principles of fairness, transparency, and efficiency, while also ensuring that land serves as a catalyst for social justice and economic growth. The policies should promote sustainable and equitable land management practices, ensure tenure security, efficient land use, and responsible land governance, and ultimately unlock the full potential of the country's land resources for the benefit of Nigeria and all Nigerians.

*Fawehinmi, an inclusion and human resources specialist/education enthusiast, is the author of the book “The Essential Guide to Land Acquisition in Nigeria.”

References:

- AUC-ECA-AfDB Consortium, 2010. Framework and Guideline on Land Policy in Africa

- Adeniyi Peter. (2011) Improving Land Sector Governance in Nigeria

- Butler Stephen (2012. Nigerian Land Markets and the Land Use Law of 1978

- De Soto Hernando. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere. 2003

- Fawehinmi Yomi (2015). The Essential Guide to Land Acquisition in Nigeria.

- Mabogunje A. Keynote address at the Land management and property tax reform in Nigeria. of Estate Management, University of Lagos, Lagos, 2003.

- PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC), Bringing Dead Capital to life. What Nigeria should be doing?

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Ayobami Ayorinde | In the last two weeks, the Federal Government unfolded some emergency measures in the agricultural sector. On July 10, the Minister of Agriculture and Food Security,

- Details

- Policy Platform

By Celestine Okereke | A feature of revenue distribution in Nigeria in the past few decades is that some federal agencies receive a percentage of the revenues they collect on behalf of the Federation.