By Ayobami Ayorinde | In the last two weeks, the Federal Government unfolded some emergency measures in the agricultural sector. On July 10, the Minister of Agriculture and Food Security,

Senator Abubakar Kyari, announced government’s plan to import 500,000 metric tonnes of wheat and maize to shore up the strategic grain reserve and the suspension of tariffs for 150 days on imported rice, wheat, maize and cowpeas. The government also disclosed its intention to distribute 20 trucks of rice to each of the 36 states and the FCT.

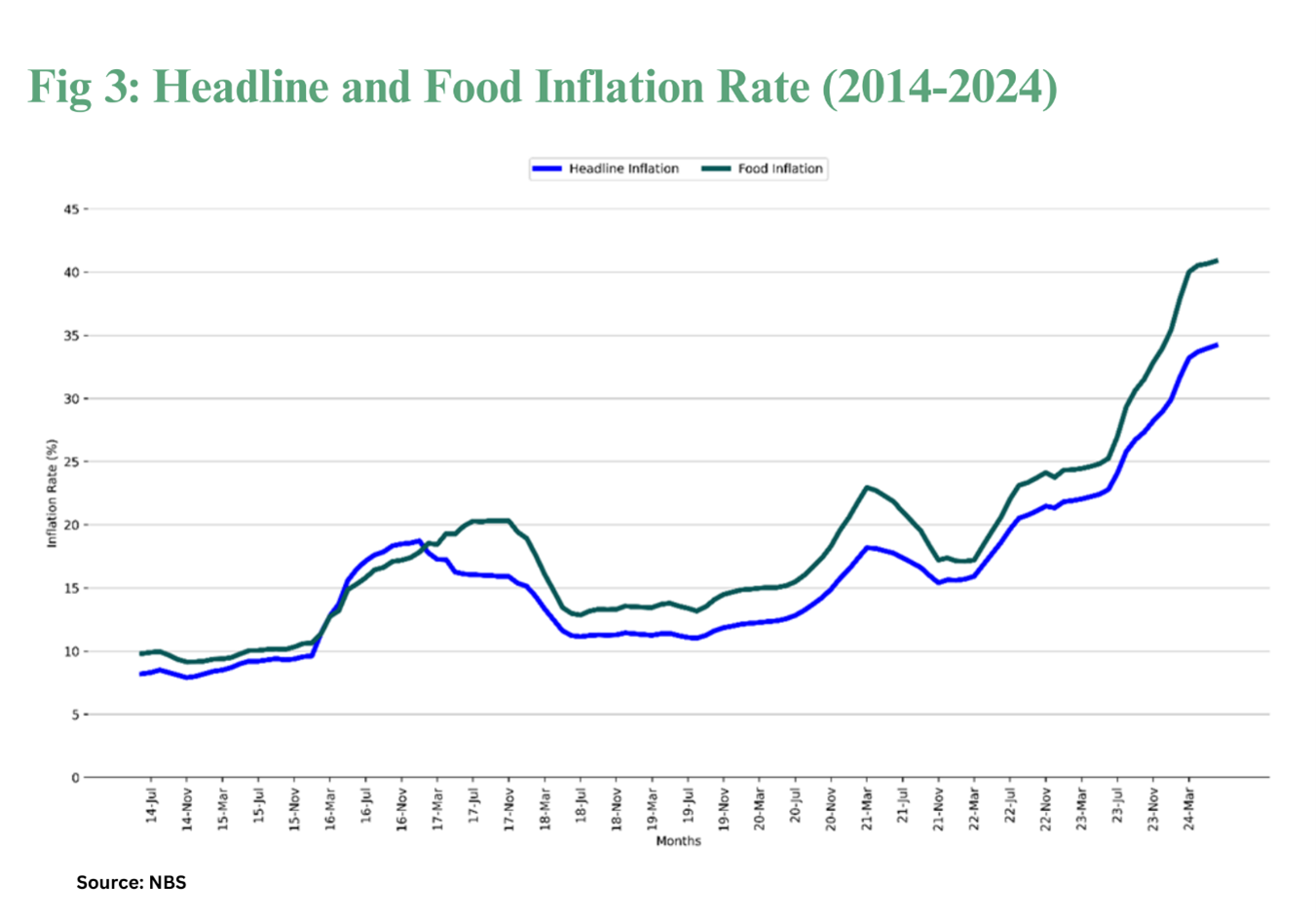

These interventions are aimed at tackling spiralling food inflation which, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, stood at 40.87% in June. These moves are commendable, even if coming a bit late. However, the best these measures can provide is some interim relief. More significant steps need to be taken to rein in food inflation in a sustainable manner and to address Nigeria’s lingering challenges with food security.

Not everyone is a fan of these interim measures. While many believe that the interventions will provide needed succour to many Nigerians struggling to feed themselves and their families at a time of intense cost-of-living crisis, others argue that the policies could undermine local farmers and local food production. Some of these concerns are valid. But the probability of food riots poses a greater risk to society as a whole and provides a good justification for government’s interim interventions which are also time-bound.

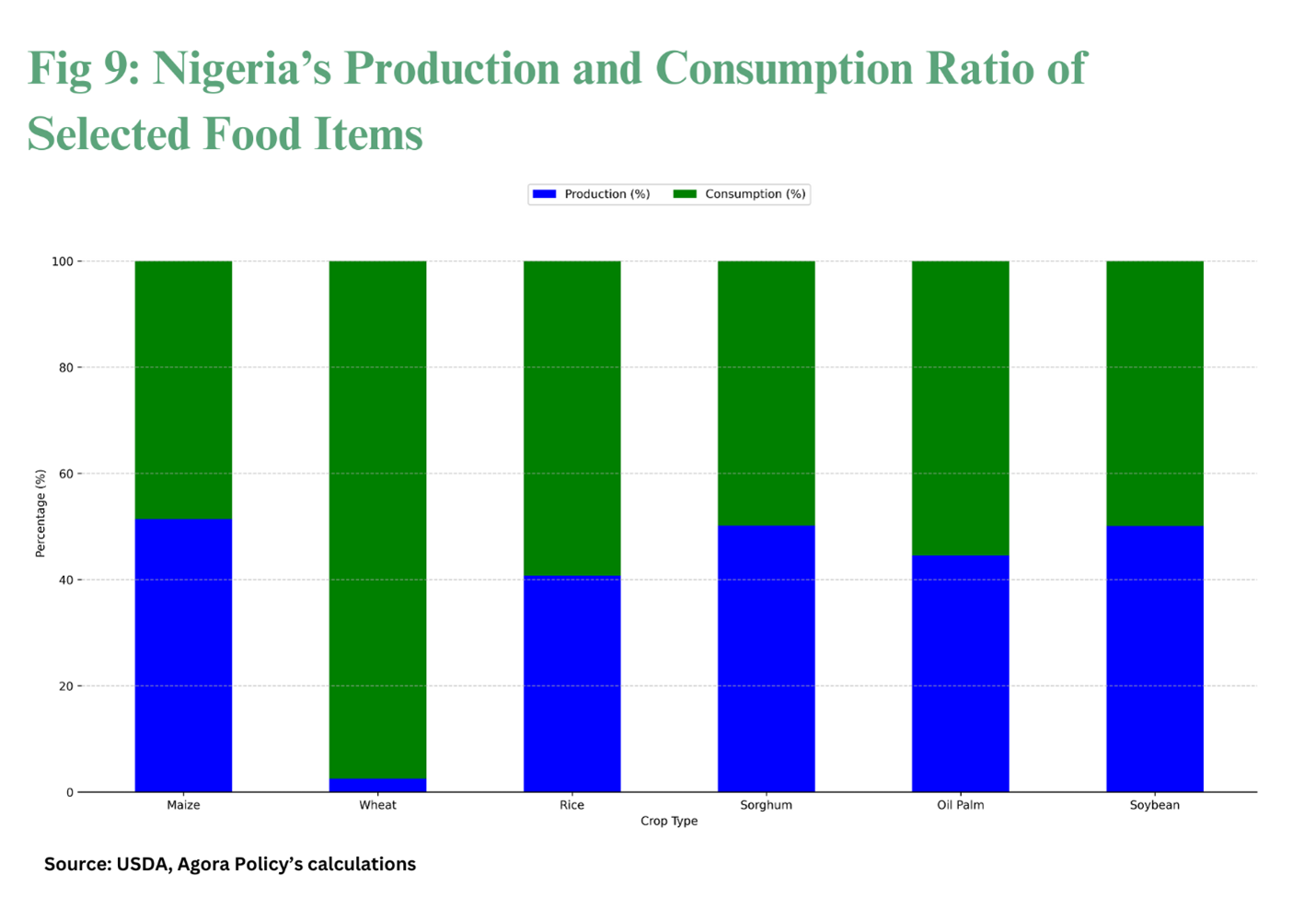

Import tariffs serve as a key source of government revenue and protect local producers from foreign competition. Before the tariff suspension, imported wheat and rice attracted tariffs as high as 85% and 70% respectively, significantly driving up their prices and the prices of the products made from them. However, given the current struggle with rising food inflation and Nigeria’s insufficient local production of some of these staples, the tariff rates had remained excessively high for too long. Protecting the interest of farmers should not be at the expense of the larger society.

With the government taking a revenue cut to achieve food price stability, this should (all things being equal) translate to reduction in the prices and increase in the supply of the affected food items. It needs to be stressed, however, that there is no such automatic guarantee. For instance, an increase in food supply might not match or exceed local demand if traders decide to hoard or to export the food items to neighbouring countries. Furthermore, some sellers may choose to maintain high prices and higher profit margins despite reduced import costs by hiding under the excuse of selling older stock. Not that there won’t be slippages, but the government needs to factor these risks into its implementation plan to ensure that the interventions provide the desired relief to Nigerian consumers.

Given that these interventions are time-bound, they are insufficient to provide a sustainable solution to the challenges of food inflation and food insecurity in Nigeria. The suspension of tariffs will end in five months, the 20 trucks of rice to the 36 states and FCT will quickly be exhausted and the 500, 000 metric tonnes addition to the strategic grain reserve is less than 2% of annual grain demand in the country. So, what happens next? New harvest should help, especially if it is good. But all of these may not make much difference, as Nigeria has fundamental and long-term struggles with its agriculture. Beyond immediate and welcome reliefs, government needs to do much more to effectively address the country’s food security challenges. It is important therefore to immediately complement the short-term measures with medium- and long-term ones.

Structural Challenges Not Amenable to Quick-Fixes

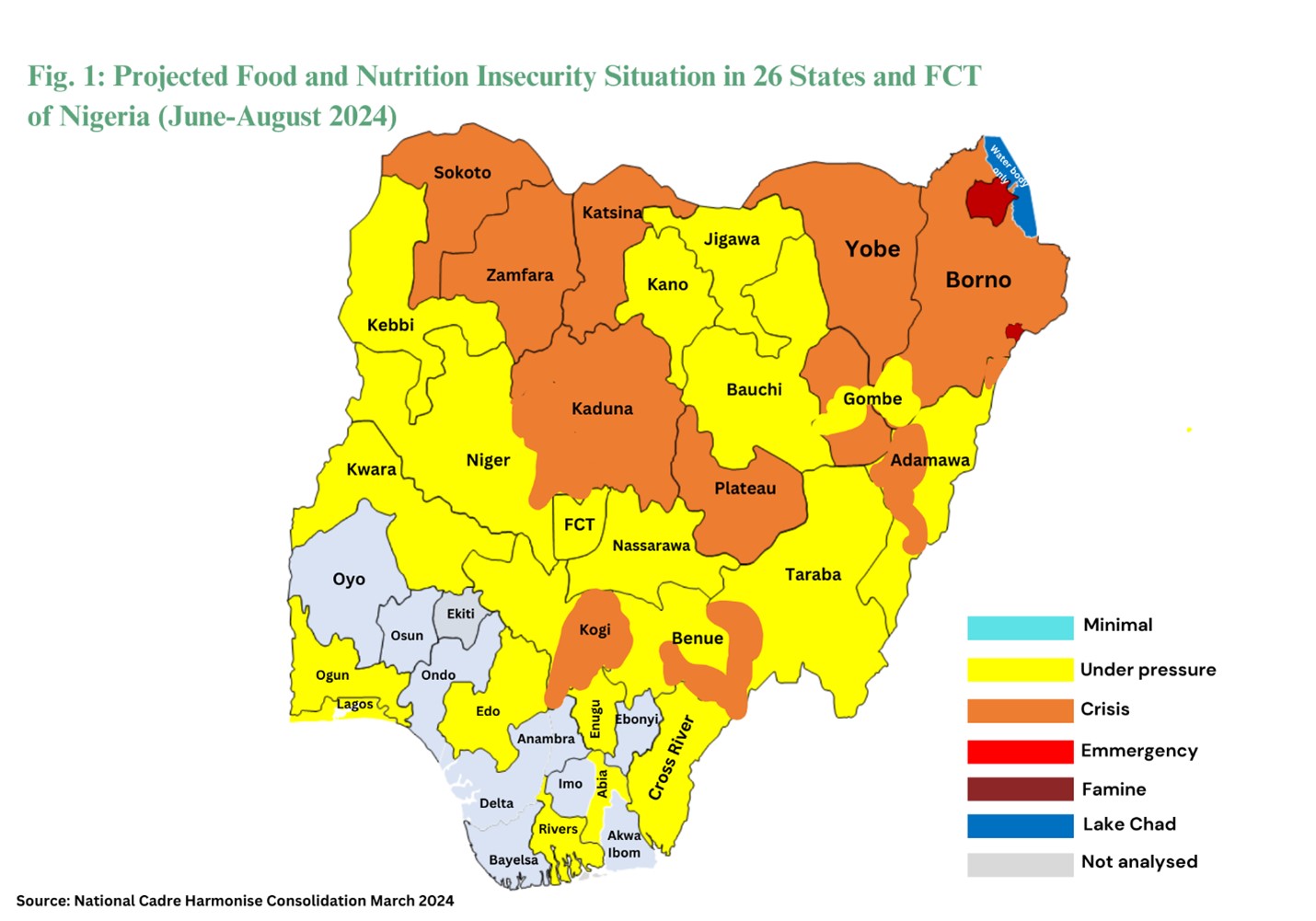

A recent report by the Cadre Harmonise, as shown in Fig. 1 below, revealed that no fewer than 24.9 million Nigerians were in the critical stage (crisis to emergency phase) of food insecurity as at March 2024. The situation was projected to worsen and the number of vulnerable persons to potentially rise to 31.8 million between June and August this year.

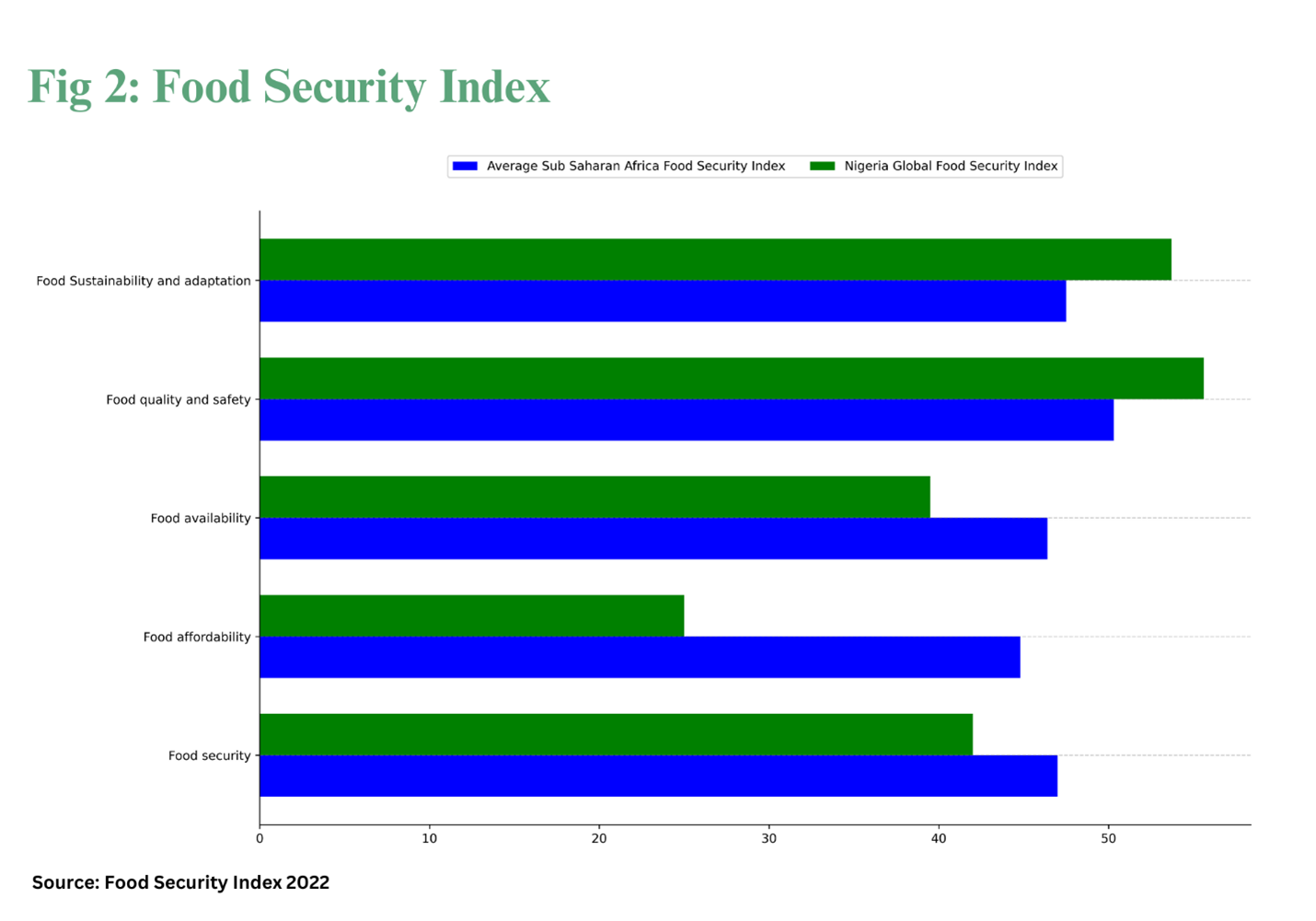

These figures simply show the effect of the country’s compounding food crisis over the years. Nigeria ranked 109th out of 125 countries on the 2023 Global Hunger Index, with a score of 28.3, indicating a serious hunger problem. Also, Nigeria ranked 107th out of 133 countries on the 2022 Global Food Security Index with an overall score of 42 as shown in Fig. 2 and falling below countries like Niger, Sudan, and Venezuela. In terms of food affordability, Nigeria ranked last globally, a serious concern in a country where on the average citizens spend about 60% of their income on food.

Food inflation has surged in the last one year by 15.62%, rising from 25.25% in June 2023 to 40.87% in June 2024. It is worth noting that Nigeria has had double digits food inflation figures for almost a decade since June 2015 as seen in Fig. 3 below.

Various factors have contributed to Nigeria’s lingering food crisis. Some of the recent ones include climate change shocks and insecurity which have affected food production in parts of the north, which is the food basket of the country. The removal of subsidy on petrol and the rapid depreciation of the Naira have significantly increased input and transport costs for farmers and traders. Additionally, disruptions in global food supply chains caused by the Ukraine-Russia war and the closure of the land borders by the previous government reduced food supply into the country.

While President Bola Tinubu declared a state of emergency on food in July last year and proposed measures such as irrigation and year-round farming, enhanced security for farms and farmers, deployment of concessionary capital to the agricultural sector, improved transportation and storage facilities for agricultural products, and the activation of 500,000 hectares of land and river basins for continuous farming, the impact of these measures are yet to be felt assuming that the measures have been implemented at all.

The increasing frequency of attacks on farmers and farming communities by armed bandits continues to threaten the country's food security. In the Northeast and North Central regions, farmers face the constant danger of terrorist attacks, while those in the Northwest are forced to pay levies to access their farmlands. According to reports, over 78,000 farmers in Borno, Katsina, Taraba, Plateau, and other northern states have abandoned their farmlands due to insecurity.

Furthermore, Nigeria still relies heavily on rain-fed agriculture, which means in most parts of the country crop farming is not done throughout the year. Variations in rainfall also delay planting seasons and cause food scarcity, as production is seasonal compared to the demand for food which is year-round. Since agricultural products are perishable, farmers are often made to sell their produce unprocessed, and at lower prices because of inadequate processing and storage facilities. According to the recent agricultural census sample report by the NBS, only 2% of farming communities sampled had access to processing facilities.

Agricultural trade within the country is still largely dependent on the deteriorating road infrastructure. The removal of petrol subsidy has further increased transport and logistics costs and marketers are burdened with multiple taxes at various checkpoints. Ultimately, they will pass on these costs to consumers.

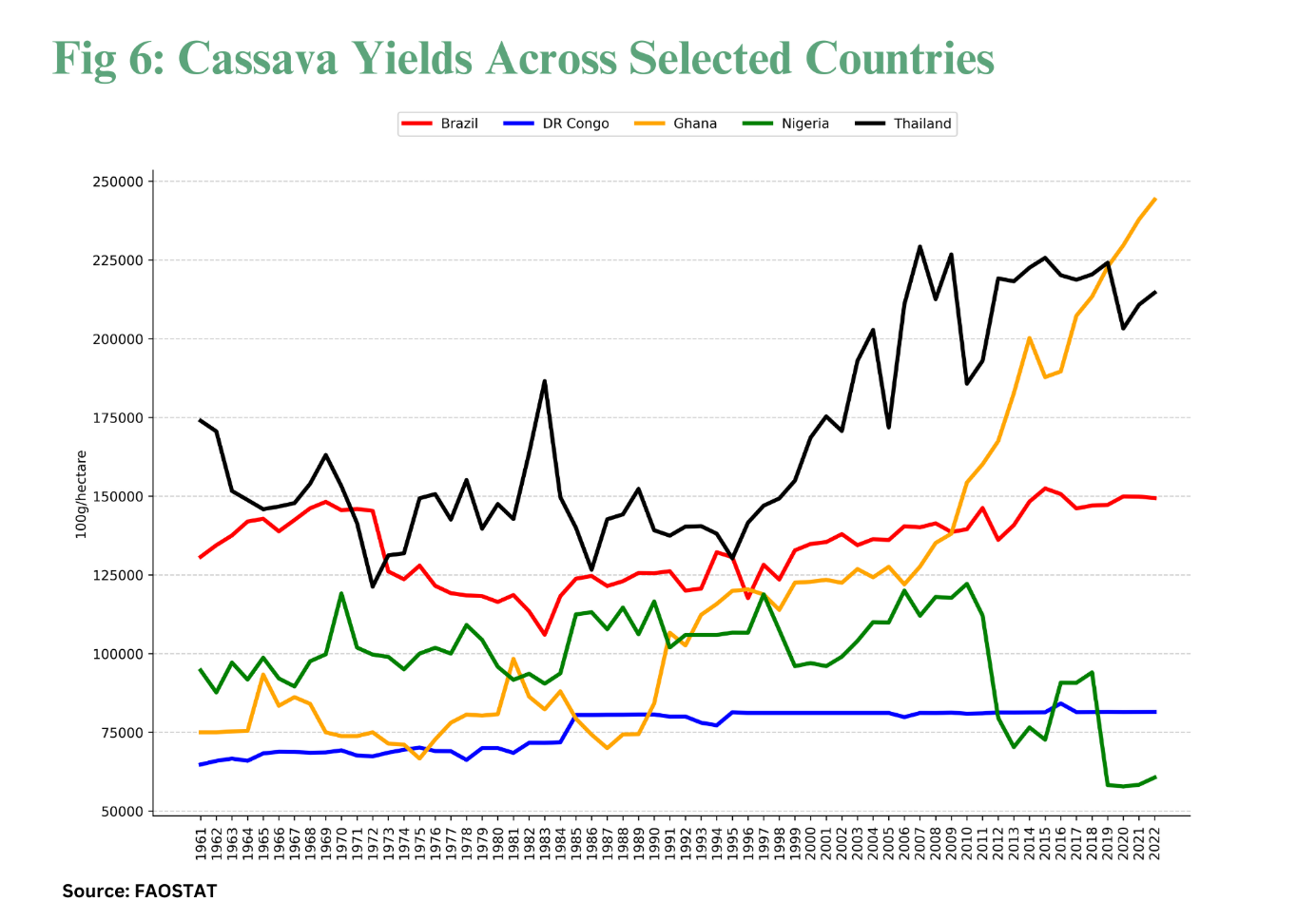

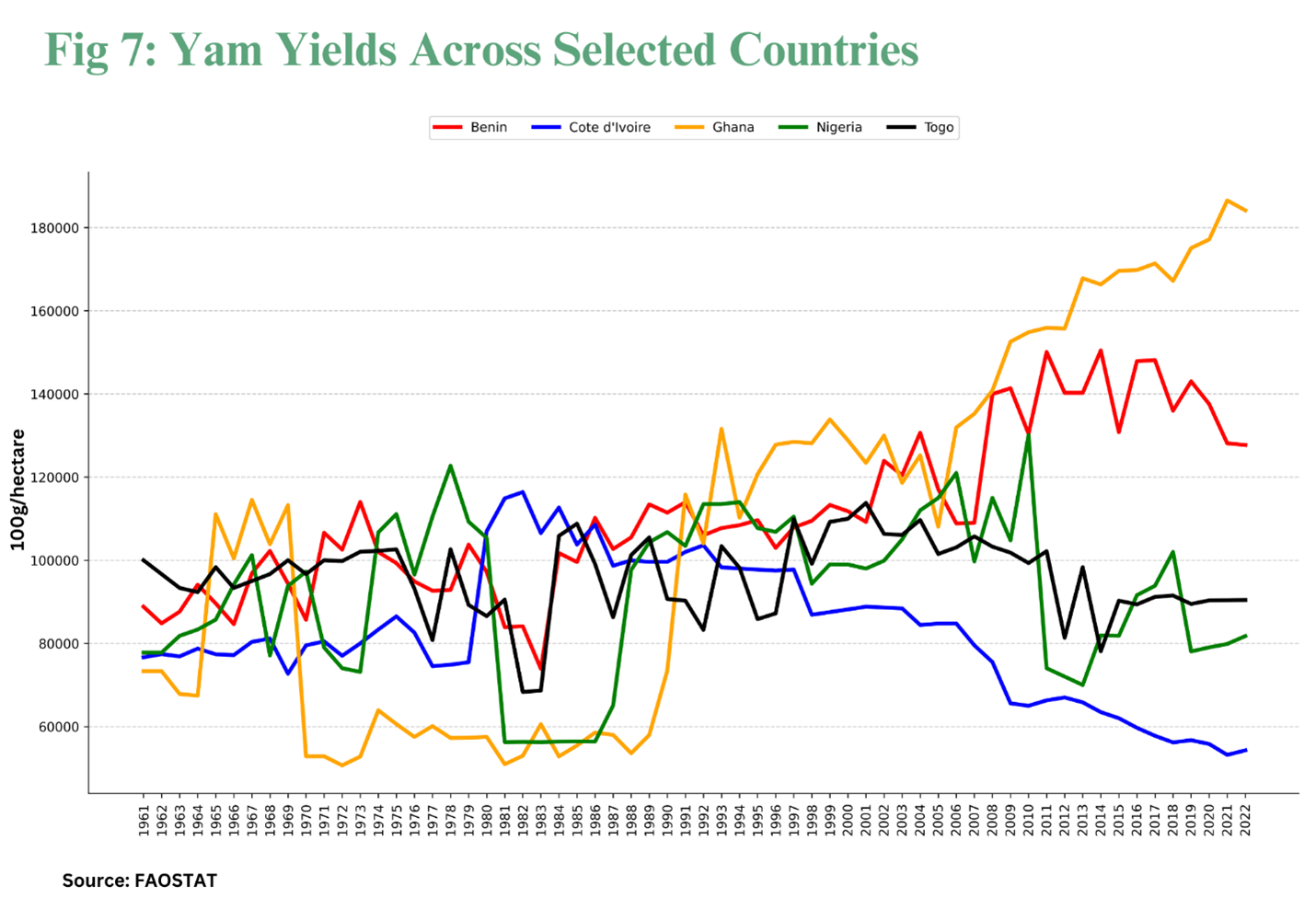

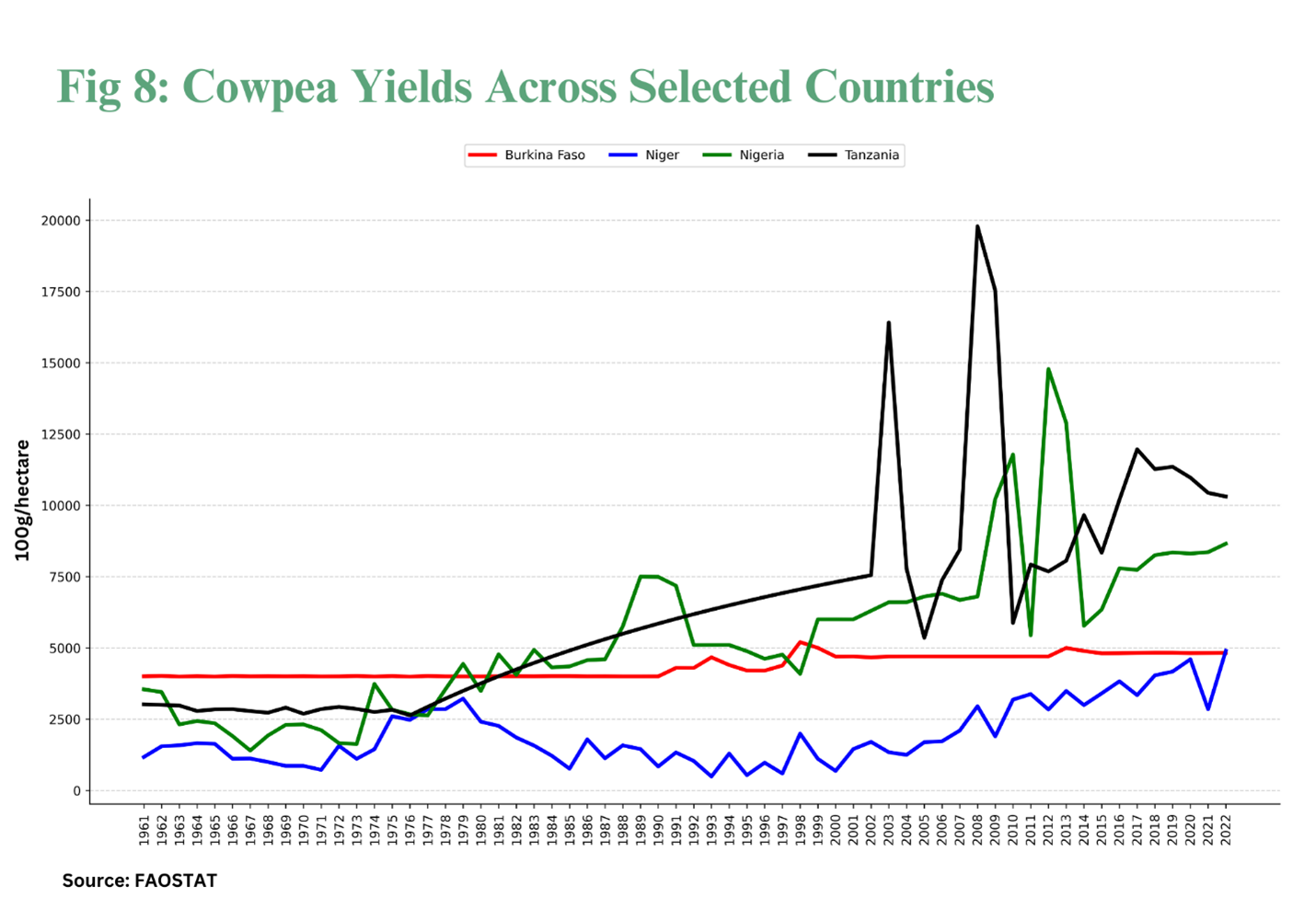

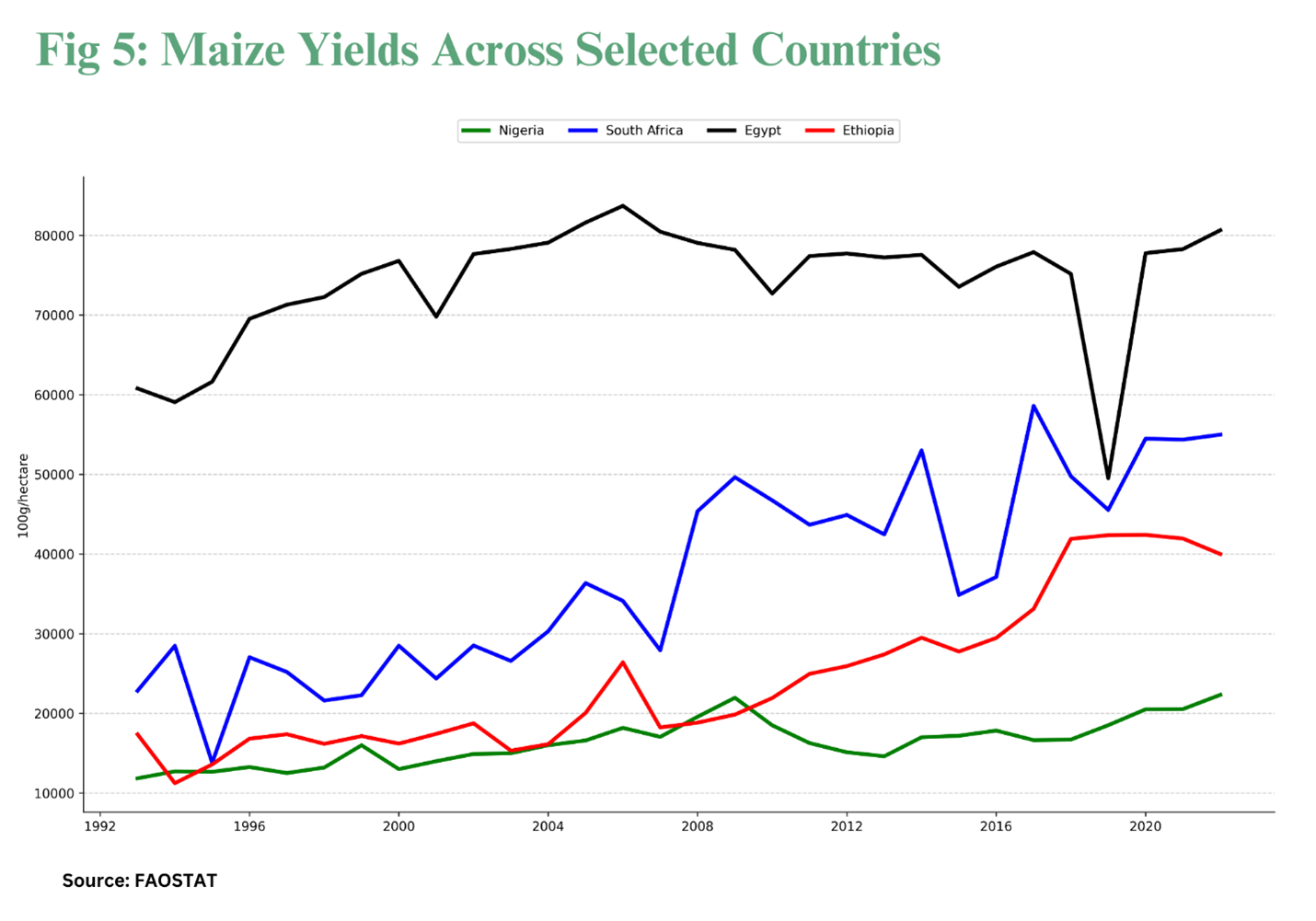

Nigeria also suffers from poor crop yields. Despite being the top producer of crops such as yam, cassava, cowpeas, and a leading producer of maize, Nigeria still experiences lower yields compared to other top producers as shown in figures 5-8 below.

A More Comprehensive Approach Needed

To sustainably address Nigeria’s lingering food crisis, the government must more closely with stakeholders to sort out many things. First on the list will be the need to prioritise addressing the security challenges in the Northern regions and other parts of the country. Enhanced security measures should be implemented to deter and swiftly respond to attacks in vulnerable farming communities across the country. Local communities should be encouraged to collaborate closely with the government in gathering actionable and timely intelligence on the activities and movements of bandits and terrorists and the security agencies should respond swiftly. The local communities are more familiar with the local terrains and dynamics, and can provide valuable information on potential threats and suspicious activities.

Since a more efficient transportation system is crucial for facilitating trade within the country, efforts should also be made to improve rural roads and enhance inter-regional transportation through the development of rail networks and better road infrastructure. Nigeria used to have rail coaches dedicated to moving agricultural goods. This should be revived. A robust rail network can significantly reduce the time and cost associated with transporting agricultural produce particularly for long-distance shipments. In addition to rail networks, improving road infrastructure is essential for connecting rural farming communities with regional markets and processing facilities. This is particularly important in remote areas where roads often deteriorate, making it difficult for farmers to transport their goods efficiently.

Additionally, reducing post-harvest losses through proper storage and processing facilities can significantly contribute to improving food security. Proper storage ensures that agricultural products remain fresh and consumable for longer periods, thereby preventing spoilage and waste. With storage in place, the availability of food helps to stabilise prices as the market is less likely to experience sudden shortages that lead to price spikes. Investing in processing facilities can also maximize the value of agricultural products by converting raw produce into a variety of goods that have a longer shelf life and higher market value.

To enhance crop yields, the government must prioritise strategies related to the adoption of high-yield and disease-resistant seed varieties, control of pest and diseases, strengthening of agricultural extension services, and investments in mechanisation and technology such as improved power supply, irrigation infrastructure and climate-smart agriculture like precision farming to drive efficiency in food production and supply and improve food security in the country in the near future.

While there are growing concerns about increasing food importation, it is important to note that imports should complement production rather than compete with local production. As a result, the government can focus on reducing tariffs on imported staple foods with a clear domestic production deficit, like wheat, while it prioritises strategies to facilitate increased local production for crops like yams, cassava, maize, sorghum, and millet where Nigeria has a comparative advantage and the potential to meet local demand.

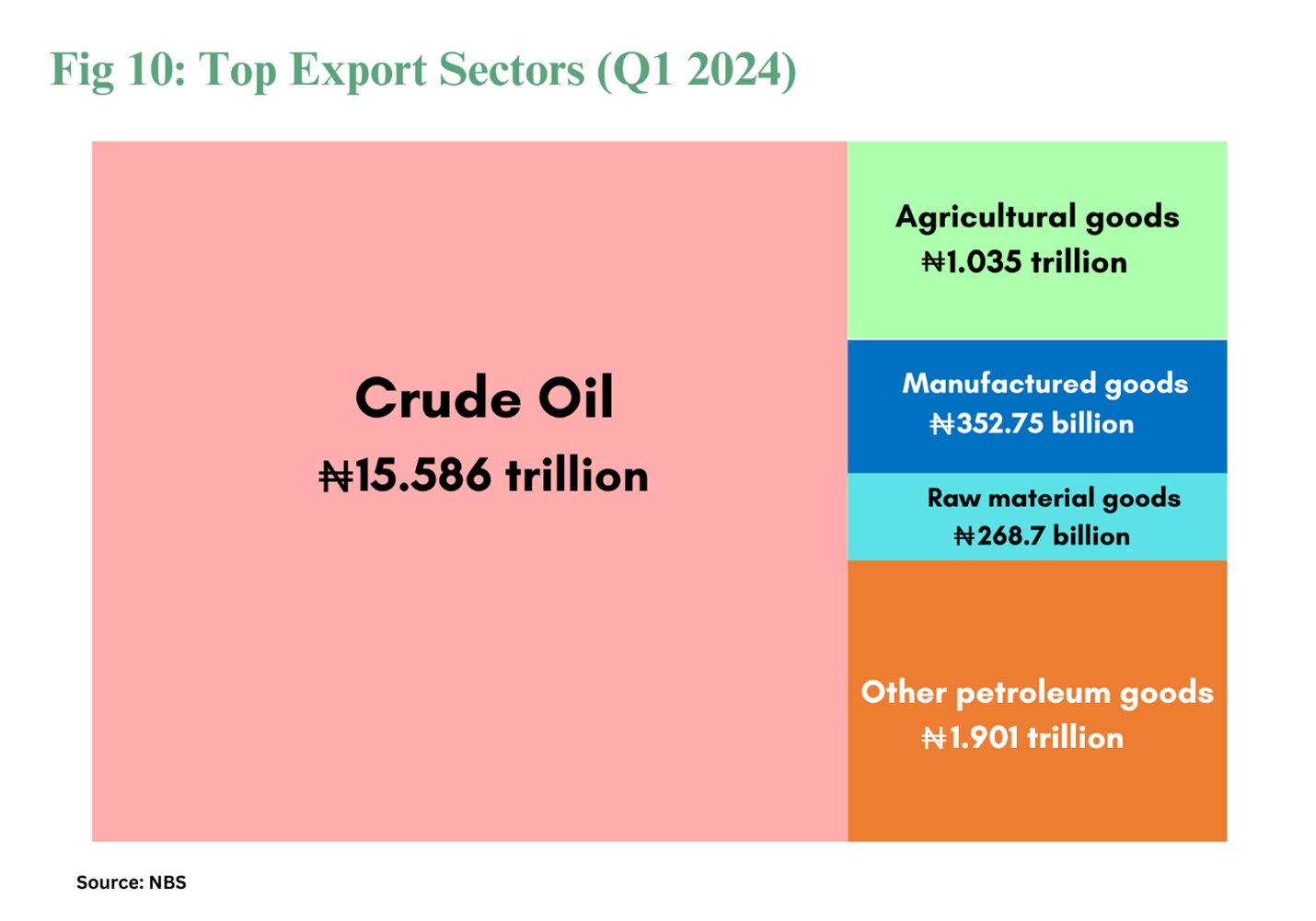

Finally, Nigeria must elevate its agricultural sector beyond production-for-consumption only and capitalise on international trade in a bid to diversify the country’s economy. According to the NBS, and shown in as shown in Fig. 10 below, agricultural exports accounted for only 5.40% out of total exports in Q1 2024, highlighting the need for increased agricultural exports.

Nigeria can leverage exports for food items where production exceeds domestic demand by transforming raw farm produce and its derivatives into processed and packaged goods with higher value. Also, implementing strict quality control measures and adhering to international standards and certifications will also ensure that Nigerian products meet the requirements of and compete in the global markets.

Conclusion

With food inflation and food insecurity reaching critical levels in Nigeria, the government must move beyond rolling out emergency interventions and tackle the structural issues like insecurity, low productivity, and inadequate infrastructure that hinder production. This approach will not only enhance and expand local food production to meet domestic needs but will also position Nigeria to become a major exporter of agricultural products, thereby increasing the size and the sources of foreign exchange, and further boosting the country's economy.

*Uchechukwu Eze contributed to this report.