Policy Memo

- Details

- Policy Memo

By Adebayo Ahmed | The new dispensation combined with quick policy actions on fuel subsidies and foreign exchange, as well as the arrest of the suspended central bank governor, has brought the question of monetary policy to the front burner. With President Bola Tinubu announcing during his inaugural speech the need to “clean” the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) as well as the need to reduce interest rates to promote MSME-led growth, the question therefore revolves around what the CBN has been doing wrong, and what is the way forward.

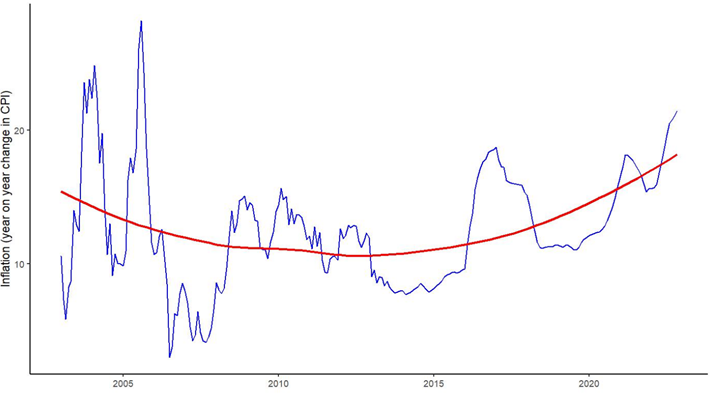

Fig 1: Inflation. Source: National Bureau of Statistics

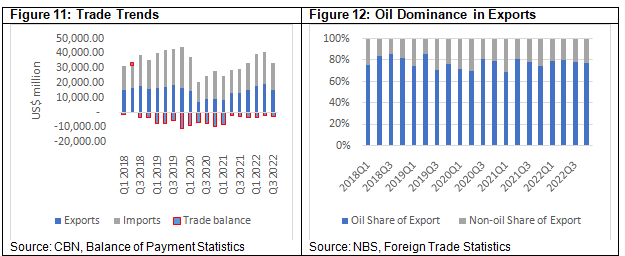

The backdrop to this question is the uncomfortably high and rising inflation which hit an 18-year high of 22.41% in May. Inflation at over 22% is a big challenge for any economy. It means that prices double in less than four years. It means that salary earners lose 22% of their purchasing power every year. It means that the government would need to generate 22% more revenue just to provide the same public services. It means that the Naira will likely weaken by 22%, less whatever global inflation is, in the next year. Inflation at 22% means that the challenge of moving the Nigerian economy forward and improving the lives of ordinary people forward is significantly harder.

This high inflation is especially worrying for food which, at nearly 25%, means that the poorest who as at 2019 already spent roughly 60% of their incomes on food, are in a very difficult position. When combined with other recent policy efforts, such as the removal of fuel subsidies, the seriousness of the challenge should be apparent as inflation has been projected to surge even higher.

Given that keeping prices “stable” or keeping inflation low is the core monetary policy objective of the CBN, then it is easy to make the case that the central bank has been, and is, failing its core mandate. If you add popular annoyance against exchange rate issues, then the scorecard is likely to be very poor.

In this note, we will argue that the failure is due to the CBN’s misunderstanding of its powers in terms of what it can and cannot do. This misunderstanding has led it down the unconventional policy route which, as expected, has resulted in higher inflation and not much else. That misunderstanding however is a good lesson for the CBN going forward, especially in the context of the new government’s zeal to set a more credible path for monetary policy.

The big trade-off in monetary policy: Taming inflation versus promoting growth

First, a simplification of the big trade-offs when thinking about monetary policy, which is really all about controlling and managing the money supply to ensure that there is just enough money in circulation to incentivize real economic growth in a sustainable way. Of course, money (today) is really just a piece of paper (or a digital record) that has no intrinsic value. That piece of paper does not cause rain, or fight terrorists, or reduce bottlenecks at the ports, or teach young people physics. In economics we like to say that in the long-run money is neutral. If you wanted more water for agriculture, you would need to build irrigation facilities; and if you wanted to fight terrorists disrupting your economy, you would need more policing and intelligence.

This neutrality of money has very important implications for monetary policy. The first is that higher levels of money supply for a given level of economic activity just means higher prices (also known as higher inflation). Imagine a hypothetical yam-eating society in which their central bank decided to double everyone’s income by a cash transfer but the number of yams available, the real yam economy, remained the same. The only outcome will be higher prices for yams or yam inflation.

In practice, economies are a lot more dynamic but the principle is the same. Controlling the amount on money supply is the key factor behind managing inflation. If your money supply grows too fast relative to your real economy then you have higher inflation, and vice versa. Ergo, if we observed that inflation was getting too high then the expected policy response would be to reduce the growth of money supply.

There are many tools for reducing the growth of money supply but the conventional primary tool is through an increase in interest rates. The logic is simple. At the margin, higher interest rates make borrowing more costly which means credit, to the private sector or governments, should reduce, and which means money supply reduces as well. On the flip side, higher interest rates also incentivize banks to park money at the central bank to collect more interest which also tends to reduce money supply. There are various other channels but in general higher interest rates tend to reduce money supply.

But higher interest rates also have other effects. Higher interest rates tend to slow down the economy. If you think of the channel through slowing credit growth then it is pretty straightforward to see how. So, the question then becomes, when faced with higher-than-normal inflation, should policymakers choose to allow higher inflation or raise interest rates to reduce inflation, even if it limits economic growth or employment?

The answer is almost always to opt for lower inflation. The first rationale behind this is because inflation affects everything, even the interest rate itself. Think for instance of our yam economy and imagine inflation was 25% a year. What this would mean is that even if interest rates were as high as 20%, the providers of credit would still be losing value. In that economy, if a person loaned out the equivalent of one yam, at the end of the tenor, the principal plus interest would not be able to buy that same yam. In essence, real interest rates would be negative. So, you would need even higher interest rates just to incentivize people to stand still in real terms.

The same dynamic works with exchange rates in an economy with higher inflation. Imagine inflation in Naira-denominated yam economy was 25% but inflation in our neighbours’ CFA-denominated economy was only 1%. It would mean the Naira would have to depreciate by about 24% relative to the CFA just to stand still. If it didn’t, then yams from our neighbors would be systematically cheaper and everyone would opt for them and our economy would suffer.

The impact of inflation is so ubiquitous, from wages to government spending to interest rates to exchange rates, that when faced with a choice, monetary policy almost always has to opt for lower inflation even if it comes with some costs.

But that is not all. Imagine our yam creditor who has to decide what “real” interest rate to charge to ensure that she doesn’t end up losing value at the end of the term. She has to guess what inflation in the future would be. If she thinks inflation will be high then she has to charge a high interest rate to make up for it. On the other hand, if she thinks inflation will be low, then she can charge a lower interest. In essence, her expectations about inflation in the future affect what she does today, and therefore affects what really happens in this yam economy today. What this means is that, even if nothing happens, if people start to expect that inflation will be high then there are consequences to that.

From the perspective of monetary policy, this means that it is not enough to choose lower inflation, but people need to believe that you will choose lower inflation and do what needs to be done to tame inflation. If people start to believe that inflation will be higher, then people start to act as if inflation is high and that results in all the consequences of high inflation even if nothing significant happens.

Supply shocks and optimal monetary response

An expansion in money supply is not the only thing that can cause inflation. Supply shocks can also have impacts on prices and inflation as well. Think about our yam economy and imagine some goats came and ate up half the yams. Given the same amount of money supply in circulation it will simply mean that prices will go up, otherwise known as higher inflation.

What should monetary policy authorities do about supply shocks? The conventional wisdom is if you think those shocks are temporary then you can try to just ignore them if they aren’t too large. But if you think those are not “shocks” but permanent changes in supply, then you have to manage money supply to reflect those permanent changes. For example, in our yam economy where goats ate half the yams, the ideal monetary response would be to reduce the money supply to fit the new reality of an economy that is only half as large as it used to be.

What monetary policy authorities typically do not do is to try to directly tackle those supply shocks with money. Remember that money is neutral and you typically cannot use money to kill goats, or construct dams, or train teachers, or neutralize COVID. It does not mean that other parties cannot do this to help tackle inflation. Other parties can. The convention is to let the other parties tackle supply shocks because in most cases the shocks are not only about money.

Even where money could be impactful, the conventional wisdom is to let the parties that are best able to find and channel that money, usually the financial sector or the government, to do what they are good at. This is because if those issues are tackled with monetary policy, then you will have to weigh the impact against the costs of higher inflation. In general, higher inflation is always worse.

In essence, even though supply shocks can have an impact on inflation, the monetary policy response to supply shocks ideally would be to be more focused and ruthless in managing money supply.

CBN and the wages of unconventional monetary policy

The recent history of monetary policy in Nigeria can be described simply as the CBN trying to use monetary policy for things that monetary policy could not do, and choosing to focus on other issues while abandoning its inflation mandate. As expected, the outcome from not choosing lower inflation has been higher inflation without any real impact on the many other things it tried to do because, you know, money is neutral.

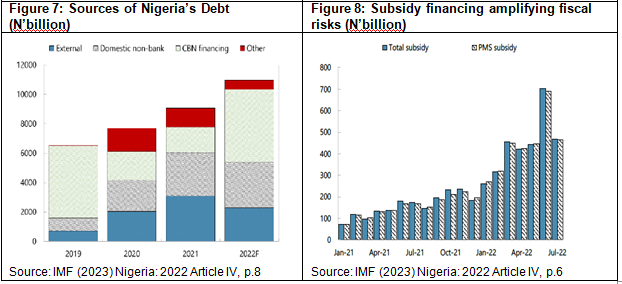

Many may have forgotten but at his inaugural speech in 2014, the suspended CBN governor, Mr. Godwin Emefiele, wrote that “the Central Bank [could not] afford to sit idly by and concentrate only on price and monetary stability”. He essentially promised to use the CBN for developmental activities such as “credit allocations and direct interventions in key sectors of the economy”.1 To be fair, at the time in 2014, inflation was somewhere around 8% and if inflation is low then there is scope for either monetary expansion or interest rate reductions. The governor chose the latter, and chose to expand money supply not through the financial sector, which is typically the better allocator of credit, but directly through its interventions and eventually lending to government.

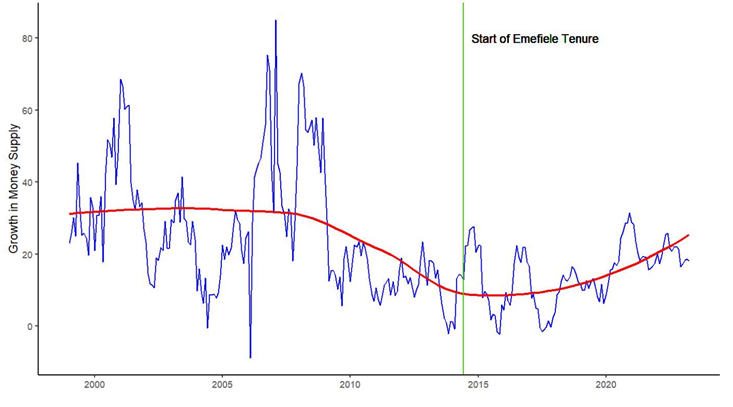

Fig 2: Growth in money supply (M2) with trend in red. Source: Central Bank of Nigeria2.

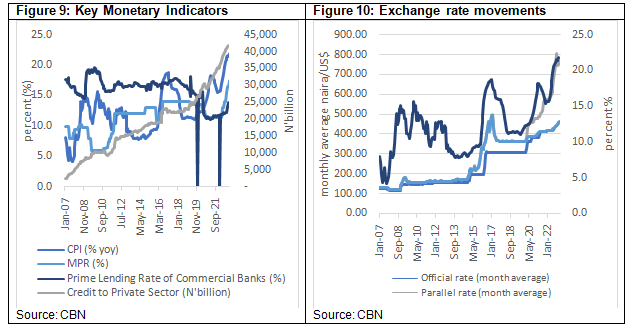

The CBN under his direction, changed from what had been a relatively successful decade of limiting money supply growth which resulted in single digit inflation, to increasing the growth of money supply. As Figure 2 shows, regardless of what else was happening in the economy, what is clear is that there was a change of trajectory and money supply started to increase under his watch. Money supply was of course completely under the control of the CBN. As we remember from our crash course in monetary policy, more money supply in a similar-sized real economy, simply means higher inflation.

Fig 3: Inflation with trend in red. Source: National Bureau of Statistics.

Yes, there have been supply shocks revolving around foreign exchange, COVID, climate change, and other security complications and so on. What is however clear is that the underlying inflation trend has been increasing, in spite of these shocks. Even if you ignore food inflation, which is typically more volatile and in our case dependent to a large extent on the weather, and focus on core inflation, the story is the same. As discussed earlier, supply shocks can and do lead to inflation but the implication is that there was even less room for messing around with monetary policy.

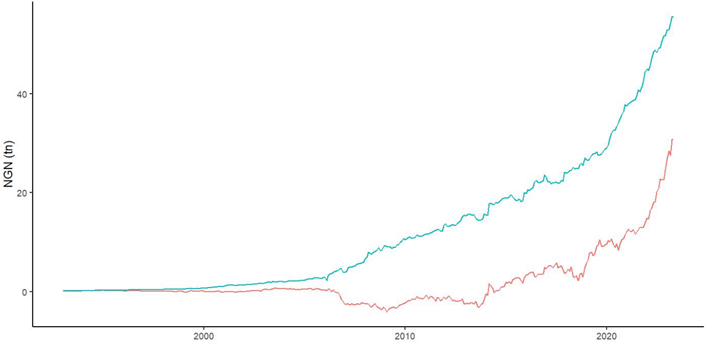

Fig 4: Credit to the government and Money Supply (M2). Source: Central Bank of Nigeria

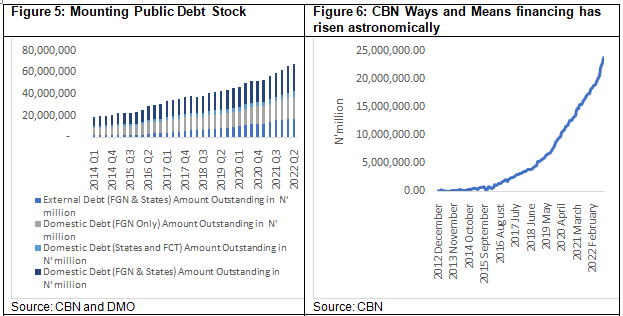

The first culprit is the expansion of lending to the Federal Government which resulted in a direct increase in money supply, all else being equal. As became clear during the final days of the President Muhammadu Buhari administration, this lending was significant with N22.7tn of this Federal Government outstanding debt securitized in May.

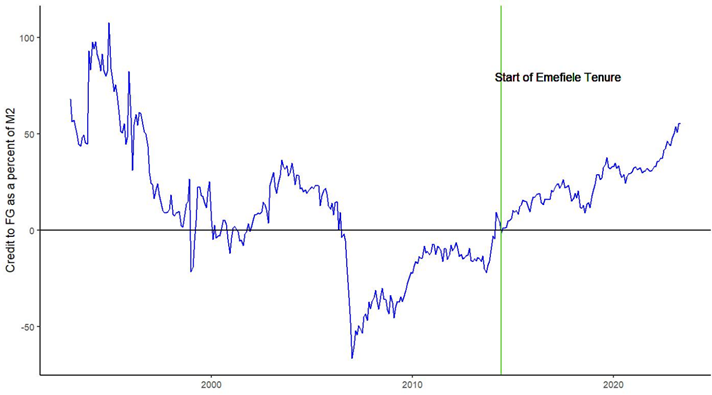

Fig 5: Outstanding Credit to the Government as a percent of total money supply (M2). Source: Central Bank of Nigeria.

For context, this was equivalent to over 40% of the total money supply3 as at April 2023. You can draw a straight line from the CBN’s financing of the Federal Government to the expansion in money supply and then to rising inflation. Previous CBN regimes had worked very hard to reduce the size of lending to the government with the resulting benefits of lower inflation for the economy as is clear in Figure 5. In fact, under the Lamido Sanusi regime the stock of Federal Government debt at the CBN was technically negative. However, that trend reversed with the outstanding debt becoming positive and growing astronomically under Emefiele.

The CBN’s special interventions also contributed their share. Figures are hard to come by on this, but there were reports of about N1.5tn to the anchor borrowers' programme, another N1.5tn on the power sector, N220bn to the textile sector, and so on. All these contributed directly to the growth of money supply and therefore rising inflation. You can argue about the impacts of these interventions but it is unlikely that whatever impacts they had or did not have were large enough to cover the negative impact of higher inflation.

The CBN tried to manage some of this by increasing the Credit Reserve Ratios (CRRs), the fraction of funds that banks have to hold in reserve, but in an arbitrary ad-hoc way with different CRRs for different banks. Although this might have slowed the growth of money supply, it was not enough given the scale of the expansion. There were also questions on the legality of implementing a CRR policy in such an ad-hoc way.

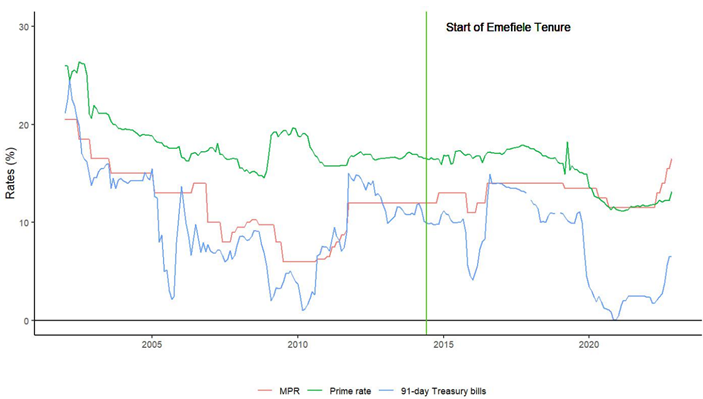

Fig 6: Interest rates. Source: Central Bank of Nigeria

The second culprit in the woe of unconventional policy was trying to force interest rates down even while inflation was going up. If you look at the monetary policy rate in Figure 6, which is supposed to be a signal for CBN’s interest rate policy, you would be forgiven for thinking that it did not change much. But in practice the CBN used administrative action to force rates down. If you look at the actual prime interest rate or the rates on government bonds and treasury bills then the direction of rates is clear. The action on rates started a long time before COVID so it cannot simply be blamed on the pandemic.

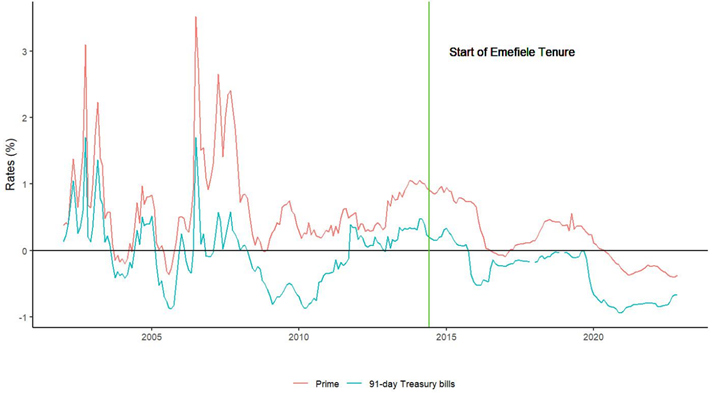

Fig 7: Real interest rates. Source: Central Bank of Nigeria and Author Calculations3.

The consequence of the action to reduce interest rates even during a period of higher than ideal inflation was that “real” interest rates became and are still negative. As we learned from our simple crash course in monetary policy, negative interest rates mean people should take their assets elsewhere. This puts even more upward pressure on inflation.

Fig 8: Inflation Perception and Expectations 4

A consequence of the CBN abandoning conventional for the unconventional was that people began to doubt the CBN’s ability to control inflation. As is clear from Figure 8, the public’s expectation of future inflation began to rise. If you recall, even if nothing else happened, once people start to believe that inflation will be higher in the future, then that makes the work to keep inflation in check even harder.

So, what’s the way forward?

The starting point is for the CBN (and given the current circumstances the executive also) to recognise the scale of the inflation challenge and the importance of getting inflation under control. As long as inflation remains high, every other objective, be it the quest for exchange rate stability or the president's agenda for increased cheap lending to MSMEs, will be much more difficult to achieve. The CBN needs to remember that its primary monetary policy objective is to keep inflation in check.

Given that inflation is currently much higher than ideal, the direction of monetary policy has to be to tighten or reducethe growth of money supply. This also means that interest rates will likely have to go up. How far up? At least to the point where “real” interest rates are no longer negative, but maybe even higher.

These actions to reduce the growth of money supply and increase interest rates are likely to be complicated by all the underhand administrative measures which were put in place to force rates down or to limit money supply growth through the back door. For example, the many administrative measures have meant that the monetary policy rate has recently no longer influenced interest rates either for government securities or at the banks, making the monetary policy committee effectively meaningless. The unwinding of the ad-hoc CRR policy, which means money refunded to banks, will also have unintended effects if not managed. The CBN will need to unwind most of these ad-hoc measures.

Given the misdirection by the CBN over the last few years, there may a tendency for the government to want to take closer control of monetary policy. This will likely be counterproductive as it has been demonstrated here in Nigeria and in other countries where governments tend to want to use monetary policy for other non-inflation objectives. Which is the underlying problem that the CBN faces today.

A better way forward would be to strengthen the monetary policy committee and place limits on CBN’s actions that fall beyond the scope of its regular monetary policy actions. One option here would to increase the number of independent members of the committee (currently only four out of 12) and/or reduce the members from the CBN and other government agencies. For instance, there is no real reason why the deputy governor for corporate services, a largely administrative role, should be voting on monetary policy. Increased oversight, to ensure that the CBN actually implements the decisions of the monetary policy committee, would also help strengthen the credibility of the CBN.

Finally, the direct sources of expansion in money supply witnessed over the past decade, specifically the ways and means financing of the government and the myriad of intervention funds will have to stop. Else, it would be equivalent to removing the plug to drain liquidity from the bathtub while at the same time turning on the taps.

As demonstrated above, not everything is within the purview of central banks. For instance, supply shocks, which are beyond the remit of central banks, are also known to drive up inflation. This in essence means that other actors, such as the governments at both the federal and state levels, can take actions to influence supply positively, which should put downward pressure on prices and therefore reduce inflation.

Lessons can be learnt from efforts aimed at tackling rising inflation around the world. Yes, central banks took actions to tighten monetary policy as they were required to but other actors took a variety of actions to put downward pressure on prices as well. For instance, the US govt took measures to ease supply chain logistical challenges that were blamed for rising logistics costs. The UN facilitated the exports of wheat and fertilizer as part of the Black Sea grain initiative to put downward pressure on global food prices as a result of the conflict in Ukraine. In Germany, the government increased investment in public transportation to manage rising transport costs. And so on. The lesson for Nigeria is that even though the CBN has a key role to play in managing inflation, and needs to play its part, the government can also make a significant difference.

For instance, improving security on farms and tackling logistics bottlenecks around moving food across the country will put downward pressure on food prices and reduce food inflation. Promoting regional African food trade, by maybe re-opening the borders and cutting tariffs on imported food will reduce food prices and reduce inflation. From a government finance perspective, improving tax collections and reducing the need for large fiscal deficits which then need to be financed will reduce inflation. We can go on and think of a plethora of actions which governments at the federal, state, and local levels can take to improve the “real” supply-side and therefore reduce inflation. In economics, we call them “structural reforms” which boost supply.

The reality of the last few years is that there is no pain-free way out of Nigeria’s inflation quagmire. But, as with the case of the fuel subsidy and the foreign exchange restrictions, the rationale for early action is clear even if there will be costs to it. From a monetary policy perspective, one of the costs is the necessary higher interest rate environment. But it will be worth it if we get inflation back under control.

Photo Credit: premiumtimesng.com

Footnotes

[1] “My agenda as Nigeria’s Central Bank Governor, By Godwin Emefiele” - https://www.premiumtimesng.com/opinion/162063-my-agenda-as-nigerias-central-bank-governor-by-godwin-emefiele.html?tztc=1

[2] The red line is a standard Loess function to distinguish between the trend in money supply growth and the cyclical component.

[3] Defined as M2 Money Supply. Source: Central Bank of Nigeria

[4] Real interest rates calculated as the difference between the nominal rates and the year-on-year change in inflation.

- Details

- Policy Memo

By Odion Omonfoman | The centrality of adequate and reliable electricity supply to individual welfare, economic growth and overall national development cannot be over-emphasised. This message is not lost on Nigeria. However, various initiatives and reforms aimed at creating an optimal power sector for the country have fallen short. The reforms initiated by the President Olusegun Obasanjo administration, leading to the privatisation of the power sector in 2014, is yet to yield the desired results.

According to the World Bank1, Nigeria has the largest energy access deficit in the world. 85 million Nigerians, representing 43% of the country’s population, don’t have access to grid electricity. In comparison, 85% of Ghana’s population have access to electricity, while 70% of Senegal’s population have electricity access2. The World Bank estimates that the lack of reliable power costs the Nigerian economy over $26.2 billion (N10.1 trillion) which is equivalent to about 2% of Nigeria’s GDP.

This is not to say that Nigeria has not made some progress in the power sector since 1999. For instance, in 1999, Nigeria had nine power generating stations—three hydro and six thermal stations—with a total installed on-grid generation capacity of 5,906 MW, but with available generation below 1,500 MW3. Today, Nigeria has up to 26 on-grid generation stations with a total installed capacity above 13,000 MW. However, available generation capacity hovers around 4,000 MW, with average daily energy output of about 100,000 MWH. Sadly, the little progress that has been made in the power sector since 1999 is neither at par with our population growth nor adequate for the energy needs necessary to achieve our economic potential. For reference purposes, Nigeria’s energy consumption per capita at 140kWh is relatively low and is three times lower than the average for Sub-saharan Africa4.

The privatisation of the power sector in 2014 was intended to address Nigeria’s power sector infrastructure and operational challenges, by reducing the direct participation of government in electricity generation and distribution, creating an efficient, contract-driven electricity market, and putting the power sector in the hands of private investors, who would bring capital, operational capacity and efficiency into the sector. Unfortunately, privatisation of the power sector hasn’t really taken government out of direct participation in the sector, nor has it improved operational efficiency in the sector.

As a matter of fact, government’s role and direct participation in the sector has not only expanded, government is currently the largest provider of capital to the sector. Since 2015, government has provided over N4 trillion in capital to the power sector supposedly managed by the private sector. Even worse, the privatisation of the sector has created a huge debt burden for the government, arising from market obligations to private investors. The market obligations were created as liabilities under the balance sheet of the Nigeria Bulk Electricity Trading Plc (NBET), which is a government entity set up to buy wholesale power from electricity generation companies (GenCos) under Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) and sell same to electricity distribution companies (“DisCos”) under vesting contracts with the DisCos.

The market obligations are mainly debts owed to gas suppliers, shortfall payments to GenCos under the PPAs, and market shortfalls arising from non-review of electricity tariffs by the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC), the sector regulator. The Federal Government has also gone on a borrowing spree to fund the power sector, particularly the national transmission grid managed by the Transmission Company of Nigeria (TCN), which is still 100% controlled by the government. Some of the loans have been used to fund the improvement of electricity distribution infrastructure of DisCos and also to finance electricity prepayment meters for end-user customers under the National Mass Metering Programme (NMMP).

Policy Recommendations for the Next Administration

Adopt a Paradigm Shift from Installed Capacity to Electricity Consumed

Electricity, however it is generated, is a commodity and has to be consumed (or stored) for electrical energy to be useful. The most meaningful measure of electrical energy in any economy is how much consumption there is. Thus, there is a need for government to stop thinking about electricity in terms of megawatts (MW) that can be generated, and start thinking in in terms of incremental megawatt-hours (MWh) generated and consumed. In other words, government should stop thinking of installed generation capacity and start to think in terms of the amount of electricity delivered, or in layman’s terms, how much electricity is generated and consumed every hour by electricity consumers in Nigeria.

This is an important paradigm shift with positive impact for government, as having such policy mind-set changes the prioritisation and allocation of public and private resources to projects, interventions and initiatives across the electricity value chain that will increase the energy output, availability, reliability and quality of electricity delivered to end-users. By the way, electricity consumers are billed on a kilowatt-hour (kwh) basis (consumption), not on a kilo-watt(capacity) basis.

Under the new paradigm, we expect the incoming administration spokespersons to make statements such as “we will increase the total electricity delivered to Nigerian households and businesses from xyz megawatt-hours (MWh)by 100%within x months”, rather than the usual statement saying “we will increase generation capacity to 20,000 megawatts (MW)”.Increasing generation capacity to 20,000 MW without most of the 20,000 MW being consumed or a corresponding increase in electricity consumption is not only meaningless but also fiscally detrimental to the country.

Increase in megawatt-hours delivered to electricity customers can be achieved if there is a seamless conversion and flow of energy from the natural gas fields to the generation stations, and from the generation stations to the high-voltage lines that transmit the energy to the national grid, and ultimately to medium-voltage and low-voltage lines that distribute the energy to end users. In this regard, the incoming administration needs to prioritise solving the interface issues and challenges across the entire power sector value chain (from natural gas-to-electricity interface, generation-to-transmission interface to transmission-to-distribution interface), building on the current initiatives and projects of the President Muhammadu Buhari government, with a strategic objective to optimise the value-for-money outcomes of a number of these projects, initiatives and interventions.

Continue with Implementation of the Buhari Administration Power Sector Programmes

As stated above, the incoming administration needs to continue the implementation of the power sector programmes, initiatives and interventions carried out by the Buhari Administration. Often times, new administrations are under political pressure to either terminate, suspend, put on hold, or create parallel projects, policies and interventions in the power sector. As an example, the administration of late President Umaru Musa Yar’Adua government suspended indefinitely the implementation of the National Integrated Power Projects (NIPP) and other power sector reform initiatives by the administration of President Obasanjo, with great negative consequences that the power sector is yet to recover from.

The Buhari administration initiated a number of interventions to address the challenges of the power and improve the infrastructure across the sector. The most talked about is the Siemens power projects, being implemented under the Presidential Power Initiative (PPI). The Siemens project is a three-phase infrastructure initiative designed to rehabilitate, upgrade, modernise and expand power transmission and distribution infrastructure across Nigeria. Phase one of the PPI is estimated at 2.3billion euros. 85% of the funding will come from a consortium of German banks and in certain instances, Development Finance Institutions (DFI) at a concessionary rate, and guaranteed by the German Export Credit Agency and other export credit agencies. The Nigerian Government will provide a counterpart funding of 15%. The implementation of the phase has since commenced, with many of the long lead transmission equipment scheduled to arrive before the end of Q2, 2023. The successful implementation of Phase 1 of the PPI will add 2GW of stranded generation capacity to the national grid, and will certainly increase the daily electricity delivered to electricity customers from the present daily average of 100,000 MWH.

Aside from the Siemens projects, the TCN has also secured a number of offshore financing to improve transmission infrastructure across the country. The Central Bank of Nigeria has also been involved in providing long-term capital to the sector for transmission and distribution interface projects. The World Bank funded DISREP is a $500 million programme to help improve service quality of DisCos in the areas of metering, loss reduction and distribution infrastructure network rehabilitation, improvement and expansion. The National Mass Metering Programme (NMMP) is an initiative aimed at closing the metering gap in the country.

The incoming administration should continue the implementation of these and perhaps other projects and initiatives of the Buhari administration in the electricity sector. While we advocate for the continuation of the Buhari administration interventions, the incoming administration should also review and optimise some of these programmes and initiatives to ensure value-for-money.

Develop a New National Electricity Policy Framework & Amend the EPSRA

Nigeria’s subsisting national electricity policy was developed in 2000. The policy has basically remained unchanged since it was developed under late Dr. Olusegun Agagu as the Minister of Power. The National Electric Power Policy was the policy document that guided the power sector reforms and gave birth to the Electric Power Sector Reform Act passed by the National Assembly in 2004 and signed into law by President Obasanjo in 2005. Since its passage, the EPSRA (2005) has also remained unchanged, despite the urgent need for more reforms in the power sector.

With the recent constitutional alteration of section 14(b) of the concurrent legislative schedule of the 1999 Constitution (as amended), it has become more imperative to develop a new national electricity policy. More so as decarbonisation and energy transition from fossil fuels to clean sources of energy are now very important aspects of any country’s national energy policy. Consequently, the incoming administration must develop a national electricity policy that reflects the electricity aspirations of both the Federal Government and the states in line with the new provisions of the Constitution.

In same vein, the EPSRA (2005) is no longer fit-for-purpose. The 9th National Assembly had commenced the process of repealing or amending the EPSRA. While the Senate repealed the EPSRA (2005) and passed the Electricity Bill 2022, the House of Representatives just passed the EPSRA amendment bill in April. It is hoped that the 9th National Assembly can conclude the legislative process of harmonising the two bills, and pass the harmonised bill for presidential assent before May 29th, 2023. However, there is no certainty that this will happen or that President Buhari will sign the bill into law before leaving office.

In the event that the EPSRA repeal/amendment bill is either not passed by the 9th National Assembly, or that President Buhari declines assent to the bill, the incoming administration should fast-track the passage of a new electricity act by the 10th National Assembly to reflect the new electricity frame work as envisaged by the Constitution and give States the unfettered rights to develop the electricity sector, including creating electricity regulatory structures and state electricity markets within their territorial boundaries.

The new electricity law should strengthen the national regulatory framework and the powers of the NERC as the electricity regulator, improve and strengthen existing electricity market structures, incentivise the market to a more efficient, contract-based market, decentralise the operations of the TCN and in general, reduce government’s participation and allow more private investments in the power sector by opening up the sector to greater market competition.

Establish a Standing High-Level Inter-Ministerial Energy Committee

Lack of effective co-ordination of the various segments of the power sector value chain is one of the causes of the dysfunction in the sector. Thus, the incoming government should consider the establishment of a standing inter-ministerial energy committee to be chaired by the Vice President. The inter-ministerial committee members should include the Minister of Power, Minister of Petroleum Resources (or such designate), Minister of Finance, the Permanent Secretaries of the mentioned ministries, the chief executives of NERC, the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) and the Nigerian Midstream and Downstream Petroleum Regulatory Agency (NMDPRA), the Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria and heads of other key agencies and departments in the oil and gas sectors and the power sector. The inter-ministerial committee’s role will be to ensure effective coordination of agencies and operators that are part of the gas-to-power value chain.

Empower States to Develop Sub-national Electricity Markets

With the constitutional amendments that grant states’ houses of assembly the power to make laws for electricity generation, transmission and distribution within areas covered by the national grid in their domains, states and other sub-national governments have finally become players in the electricity market. The incoming administration should work with the states to develop the electricity markets within their localities.

State governments should be encouraged to take steps to begin to develop the electricity resources within their areas in collaboration with the Federal Government and under the framework of the new national electricity policy and amended EPSRA. That means the incoming state governments will also need to develop the right electricity policy framework for their states, and develop the right legal and regulatory frameworks that would create efficient and competitive electricity market structures, which can help them to attract needed investments into the electricity market. Also, states should be encouraged to drive rural electrification.

Improve the Energy Mix &Address Energy Transition Issues

Nigeria’s energy mix consists of fossil fuel and renewable energy sources, mainly hydropower generation and increasingly generation from solar energy. However, our energy mix is still dominated by fossil fuel—natural gas and diesel/petrol (largely for self-generation). This is understandable as Nigeria has Africa’s largest crude oil and natural gas resources. However, this presents a problem for Nigeria as the world moves to cut fossil fuel consumption in order to achieve carbon neutrality (net zero CO2 emission).

At the United Nations Climate Change Conference event in Glasgow (COP 26), Nigeria committed to carbon neutrality by 2060, and to this effect has unveiled its Energy Transition Plan (ETP). An Energy Transition Implementation Working Group (ETWG), situated in the Office of the Vice President, has been established to drive the implementation of the plan. In the ETP, Nigeria puts forward a robust argument for the utilisation of its vast natural gas resources as a transition fuel for its energy requirements. It is reassuring that the World Bank in a recent publication recognises that natural gas can be a transition clean fuel for developing countries like Nigeria with vast natural gas resources and existing natural gas generation plants.

Consequently, the in-coming administration must continue the implementation of the ETP to achieve a faster transition to carbon neutrality by 2060. There needs to be focused investments at targeting new investments in additional power generation into renewable energy power generation sources such as solar and hydropower energy sources. At the moment, there is no solar energy generation into the national grid – and for obvious reasons ranging from grid connection, grid instability, existing stranded generation and payment assurances for the power to be produced.

However, it is high time that a grid-based, solar energy generation plant is established to optimise our power generation resources and reduce the percentage of fossil fuel in our national energy mix. Beyond having an on-grid solar power plant, there needs to be continued and sustainable investments in off-grid renewable energy generation, such as mini-grids, to serve rural communities and underserved communities. However, this should be done with greater collaboration between the Federal Government agencies responsible for rural electrification and the state governments.

Resolve the Privatisation Puzzle

The privatisation of the power sector is one of the most controversial privatisation exercises so far in Nigeria. A lot has been written about the privatisation but suffice to say that the Eldorado promised with the privatisation of the sector has not yet materialised. Many would blame the Federal Government at the time for forcing through a privatisation of the power sector that clearly was not at the stage to be privatised. But this is neither here nor there. The task is to address whatever gap exists.

This is not to say there has not been any progress in the power sector since privatisation. As a matter of fact, the privatisation of the sector increased total available generation capacity since 2014, as core investors in the successor GenCos invested to rehabilitate and restore installed capacities in some GenCo plants. For instance, the core investors in Egbin, Kainji, Ughelli and Jebba power plants have restored the installed generation capacities for these plants.

At the heart of the seeming failure of the power sector privatisation exercise is the inability of the electricity industry to achieve a contract driven, regulated market as envisaged in the power sector reforms. Only recently, it was reported that the partial activation of contracts in the sector spearheaded by the NERC in June 2022 has collapsed. Without activated contracts (PPAs, Vesting Contracts, Gas Supply Agreements, etc) amongst market participants in the NESI value chain, the benefits of privatisation may never be realised.

Consequently, the incoming administration should prioritise the resolution of the privatisation conundrum, particularly with a view to ensuring a “sensible activation” of contracts in the industry. By “sensible activation” of contracts, we mean allowing more bilateral negotiations, rather than an imposition, of market contracts amongst parties in the industry, under the regulatory oversight of the NERC.

The in-coming administration also needs to look at re-privatising some of the DisCos that have been taken over by lenders due to default by core investors in meeting the acquisition loan repayment terms to the lenders, or under some form of administration by the NERC and the CBN. The failed DisCos in administration should be broken into smaller franchise areas preferably along state boundaries, and privatised as new entities. Lastly, there is the “unspoken” issue of the payment of the huge market debts in the sector. For instance, GenCos claim that they are owed over $1 billion by the NBET. It is unclear how the new government would address the payment of these debts.

Reversing the privatisation of the power sector should not be contemplated under any circumstance. The privatisation process has built-in contract provisions to address the failures of any core investor under their performance agreements. What is needed is for the government to activate these contract provisions, provided the government has also met its own obligations too to core investors.

Improve Gas Supply to the Power Sector

As earlier stated, Nigeria’s energy mix is largely driven by natural gas. Consequently, the unimpeded availability and supply of natural gas to thermal power stations is most critical in attaining incremental megawatt-hours of electricity consumption by end-users, transmission and distribution infrastructure permitting. While Nigeria has the largest natural gas reserves in Africa, our power generation plants engage in a daily struggle to get enough natural gas to run their gas turbines.

Thus, improving gas supply to the power sector will require addressing the bottlenecks in the gas–to-power value chain. These bottlenecks include insufficient investments in gas-to-power infrastructure, and gas-to-power pricing and timely payments to gas suppliers for contracted gas delivered to power plants. From its policy document, the incoming administration plans to introduce a “Nigeria First” policy to prioritise the utilisation of Nigeria’s natural gas resources to electricity generation before export. This will be a welcome policy, if developed and implemented.

However, the issues around gas supply to the power sector are also anchored around sustainable investments in natural gas exploration, development and production. Equally important is robust security and protection of oil and gas infrastructure across the country. Thus, any “Nigeria First” natural gas utilisation policy must seek to address these upstream and downstream issues in the oil and gas sector.

Conclusion

There is a temptation to delve into more tactical issues and challenges in the power sector such as resolving the metering gap, estimated billing, resolution of financial distress in the power sector and other operational issues affecting the electricity industry. Putting together the tactical plan to resolve the issues should be left with the power sector team to be assembled by the incoming administration. Some of the recommendations here can serve as guides to the incoming president in thinking about the critical issues in the sector and in setting the terms of reference for his power team.

[1]https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/02/05/nigeria-to-improve-electricity-access-and-services-to-citizens

[2] https://ourworldindata.org/energy-access

[3] National Electric Power Policy Document, 2001

- Details

- Policy Memo

By Bolaji Abdullahi | Nigeria’s return to democratic rule in 1999 coincided with the end of the first decade of a global commitment to the goal of Education for All (EFA) and the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), focused on achieving universal basic education, especially in the developing countries, as one of its core objectives.

However, while many countries still struggle to achieve the goal of universal education, a strong consensus has emerged over the years that although basic education is important, no country has achieved growth on the back of mass literacy alone.

The compelling argument for greater investment in university education, relative to other levels of education, flows from the strong evidence that better graduates have greater positive impacts on economic growth as well as the realisation that the 21st Century global knowledge economy requires more than literacy.1 The transformation of our public university system, where 94% of the undergraduates within Nigeria are enrolled, should therefore be integral to our vision of economic growth and competitiveness.

The promise of national development must reflect in our commitment to transforming the public university system to make it more efficient and able to meet the skills, knowledge and research needs of our country now and in the future. In seeking to realign our public university system with our national development objectives, we must ask four critical questions:

- What are our development goals over the next 15 years?2

- What human resources would we need to achieve these goals?

- How many of our citizens of university-going age would we require to have degree-level qualifications in the identified areas of need within the same period?

- What research priorities do we need to pursue and promote in order to meet these goals?

Attempts to answer these questions will highlight major problems in our current attitude to public university education which in turn has conditioned how we structure, operate and fund the system. The endemic corruption, inefficiency, ineffectiveness, inequity and lack of accountability that characterise the system merely thrive on a fundamental failure that cannot be addressed by interventions that merely target any of the symptoms in isolation. What we require is a system-wide reform that addresses the three critical elements of governance, funding, and quality assurance based on a rethinking of the entire public university education itself as a driver of national development objectives.

-

Rethinking the Governance of Public Universities

The central issue in governance is that of efficiency and service delivery. What kind of governance regime is best suited for the kind of services that the public universities are expected to provide? At the heart of this question in Nigeria is the issue of autonomy: the degree to which each university has the freedom to operate independent of the government authorities that set them up and fund them.

In Nigeria, universities are governed by the National Universities Commission (NUC), whose establishment Act of 1974 gives it controlling power over the university education system, including what departments or academic units they run and what they teach; what funding they receive and how; what personnel they hire and the conditions of service attached to such personnel; what their research needs are; and “carry[ing] out such other activities as are conducive to the discharge of its functions under this Act3.” Many university administrators and lecturers regard the NUC as a major impediment to innovation and creativity in the universities.

Global trends also suggest that less government is better for universities and that universities function best when they are self-governing. Lant Pritchett, a professor at Harvard University, used the spider and the starfish to illustrate two kinds of systems. The spider system is that in which all organs and parts of the body are centrally controlled, while the starfish allows for a level of control but grants freedom to each of the limbs to operate with significant autonomy. A pure spider system, Pritchett says, pulls responsibility for all functions to itself, especially through financing; whereas a starfish system creates local operation which,

“Pulls apart all of the many functions and activities and allocate those across the system such that the local component of the system provides a constant stream of innovation and new ideas and can use the local nature of the operation of the system for thick accountability…while the national level provides a framework for standards and monitoring and evaluation performance4”.

The starfish approach will fit squarely within a system of embedded autonomy which allows the university the flexibility to explore and establish local and international relationships and partnerships while government involvement is scaled back to quality assurance and monitoring compliance with national regulations. Another major advantage of the starfish system is that by granting autonomy to the local components, it also ensures that a problem with one of the components does not cripple the entire system.

By granting autonomy to each of the universities to negotiate contract terms with its staff based on its unique capabilities and local conditions, the government would have addressed the problem posed by the principle of collective bargaining which has turned the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) into a disruptive force over the years. Of the eight identified issues that have formed the basis for ASUU’s perennial strikes, five are directly related to issues of conditions of service and remunerations5.

Granting autonomy to the universities along this line will not necessarily save the government money, but it will achieve three things. One, it will bring stability to the university system; two, it will ensure that the lecturers are competitively and equitably remunerated; and three, it will enable the government to focus on her quality assurance functions as an objective arbiter.

The argument for more equitable remuneration of lecturers is central to attracting and retaining the right calibre of lecturers and professors. The current system that pays lecturers in different contexts and with different quality of outputs the same salary just because they are on the same “salary scale” is wrongheaded and suboptimal. However, this can only be corrected if each university is at liberty to negotiate salaries and other benefits with its lecturers.

University lecturers should be employees of their universities not those of the Federal Government or the state go vernments. Essentially, what we require is a system that fosters high-level competition for resources and even for students. Under the current governance system, the universities lack the incentive to do anything differently. Neither the funding they get nor the students that come to them depends on the quality of what they offer to students either in terms of learning or living experience or the quality of their research outputs.

Autonomy will create the condition for each university to develop at its own pace, based on real accomplishments in research, in teaching and in their contributions to national development goals. It is interesting to note that “university autonomy and academic freedom” has been one of ASUU’s key demands. Their desire is to free the universities from what they consider as the stranglehold of the NUC. The obvious implication of this, however, is that the NUC must undergo its own reform to enable it repurpose itself for its coordinating and monitoring role in a new governance system.

2. Changing How Public Universities are Funded

In respect of funding, two factors need to be considered. Effectiveness: are they being adequately funded? Efficiency: are the funds being spent on factors that are directly relevant to delivering the best results, especially in the core task of teaching, learning and research? The current funding system does not meet either of the criteria. The chief source of funding for public universities in Nigeria is the government, whose intervention however accounts for only about 44% to 60% of what is required to run a university effectively6. This means that at any given time, the funding deficit is between 40% to 56%.

Table 1: Allocations to Federal Universities in the 2023 Budget

Source: Budget Office of the Federation

Table 2: 2023 Allocations to Federal Universities: Percentage of allocation to personnel and overheads

Source: Budget Office of the Federation

Table 2 indicates that between 86% and 96% of the federal allocations of these four universities goes to personnel cost alone. This leaves a range of 0.7% to 1.4% and 2.2% to 7.2% for overhead and capital respectively. What this means in essence is that our federal universities are existing mainly to pay salaries, with hardly much left for the other operational costs and for provision and maintenance of infrastructure for teaching, learning and research. Funding effectively and efficiently would require a major paradigm shift in how we view public university education generally and how we fund it.

If we take the budgetary allocations to the universities as standing in lieu of tuition, this should be regarded as subsidy. However, as Table 2 has shown, what the government has done over the years is to subsidise personnel cost of the universities, rather than the students who should enjoy the subsidy.

A major step-change that is required here is to target the subsidy payments around students’ enrolments rather than the administration of the university. What this does is to place the students at the center of the university planning, with all other expenditures, including personnel, overheads and physical development, now revolving around the students and their needs. This also ensures an objective parameter for allocation of funding, one that is focused on output rather than the current input-based approach. Running a university costs a lot of money.

Costs are incurred almost on a daily basis. One Vice Chancellor reported spending about N40million monthly on diesel alone to keep the generators running, this is in addition to the cost of the main electricity supply. The university therefore spend up to N100million on power supply alone in a given month. Infrastructure and vehicles maintenance, fueling of vehicles, re-agents and other consumables for the laboratories, sporting activities, all these are covered under the overhead costs, which are released to the universities on a month-by-month basis.

However, interaction with several university heads reveals that while the budget for personnel is released 100%, they hardly get more than 50%of overheads allocation in a given year7. However, even if all the overhead allocation is released, it is hard to imagine how it could meet the monthly cost of running the university. For example, the University of Nigeria Nsukka (UNN) with an overhead allocation of about N203 million in its 2023 budget has a population of 36,000 students. To start with, it means that UNN has an allocation of N16.9 million per month for overhead. But more interestingly, it means that, minus personnel cost, the university has only N5,638available in a year as running cost for per student.

Even if this amount is added to the fees charged by the university in a year, the total available per students will be about N67,000 or $145. This applies to all federal universities in Nigeria. The Fallacy of Tuition-Free Education The two organised ‘vital constituencies’ for government in producing education are the students and the lecturers. The two constituencies appear to want the same thing: university education that is accessible to all who can meet the entry requirement, that is of high quality and that is free of charge.

Although this is more like a pie in the sky, government has continued to give the impression that it is possible to achieve. This has resulted in a lose-lose situation for everyone involved. Government’s best funding efforts continue to run short, the vital constituencies are permanently disgruntled, and the system continues its steady decline because government has been funding the administration of the institutions rather than education itself.

Table 3: Fees charged by some public universities in Nigeria8

In contrast, Table 4 shows the fees charged by some private universities in the current year.

Table 4: 2023 First Year fees for some private universities in Nigeria9

It is possible to argue that private universities run on a business model and will not operate at a loss. Nevertheless, the fees they charge may provide useful insights for determining what might be a realistic cost of providing university education in Nigeria. It is interesting to note that American University of Nigeria in Yola actually calculates its fees per credit units offered by the student10.

Even if we account for profitability, it is difficult to understand how University of Ibadan can reasonably charge a maximum fee of N36,800 in a session for a course that AUN, Yola charges more than twice the same amount to teach a single credit. Best practice is to fund university based on the needs of students. Money must be made to follow the students.

We need to determine what is required to deliver university education to each student, do a realistic costing and pay the universities accordingly or arrive at a cost-sharing arrangement, with government bearing most of the costs. It is understandable why government may want to persist on the outmoded policy of zero tuition, but no one is helped by it, not least the students who are mostly being rolled through the university with no prospect of real employment because they have not had the opportunity to acquire real skills.

Government needs to allow introduction of cost-reflective tuition or should pay the university full equivalent of what they would ordinarily charge as tuition or provide alternatives that guarantee realistic funding for the universities. Like Kosack argued “in the absence of a well-functioning private education market, where most consumers are unable to afford education without subsidy, there are only two options: government continues to pay subsidy or lower the fee to make it available to everyone11.”Kosack’s assumption is that there are fees to lower.

But what happens where there are no fees at all, and government cannot pay enough? In the current fiscal climate, it is unlikely that government can afford to give the universities all the money they need to function effectively. Government therefore needs to invite parents to shoulder more of the financial responsibility. If it is clearly defined as a means of improving quality, which will enhance the employability of the students upon graduation, it would not be a totally strange proposition.

Afterall, as parents lose confidence in the public primary and secondary schools, they voted for fee-paying private schools. It is indeed curious that parents who were able to pay fees running into hundreds of thousands for private basic education would expect to pay next to nothing for university education. Below are some options that can be explored to improve the pool of funding for our public universities and ensure that students from poor homes are not denied access to university education.

- Guaranteed Loan through the Education Bank

The issue of a federally-backed Education Bank has been in the works for about three decades. Now is the time to give it real traction in the context of the funding reform. It is a great opportunity that the National Assembly as well as some civil society actors have backed the idea over the years12. Once again, the only voice of dissent is ASUU, whose president declared in 2022 that “ASUU will never support the issue of Education Bank because the poor will not benefit from it.”13

It is not clear from this statement whether ASUU is opposed to the idea of students’ loan because it thinks the scheme would constitute a debt burden to the students or because the union fears that the loans might not be awarded to intended beneficiaries. Whatever the case, concerns should be addressed and the idea of an Education Bank must be framed as part of the efforts to improve quality of education generally (including to ensure that the public universities are well funded and the lecturers can be well paid) and as a means to support indigent but talented students who need university education for career progression.

Affordable loans, with repayment tied to salaries earned upon graduation will ensure that children from poor homes are not excluded from university education because their parents are too poor to pay. One major reason the idea of a students’ loan scheme may not be attractive, especially to a government seeking to shift costs, is that the risk of people defaulting is high. Education is a bad collateral.

A bank can recover a house from a defaulting customer, but education cannot be recovered from a customer who fails to pay for the obvious reason that she is not able to get a job after graduation or because she has simply relocated to another country, leaving no contact address. There is thus the risk that government might still end up paying for defaulters, except adequate risk-mitigating strategies are put in place. In the context of a full subsidy, the alternative is for the government to give out scholarship vouchers to students which would stand as guaranteed promissory notes that the universities could redeem with the government.

If the government is able to redeem the vouchers in full and on time, it would have ensured that the universities get paid the agreed amount for each student. But this is unlikely to happen. It is important to emphasise that the conversation around an Education Bank is in the context of the need to introduce tuition payment in the university, which has become inevitable as the only realistic and sustainable pathway to effective funding of the universities.

Even in the face of high risk of default, there are other benefits to the system in the idea of a student incurring a debt to fund her education. It turns the parents and the students into active financial stakeholders and gives them a skin in the game. Perhaps, the most important effect is that it is likely to engender a new attitude towards learning and even teaching.

As the indebted students begin to demand value for money, horizontal accountability will be strengthened and quality is likely to improve generally. As quality of graduates improve, employability is likely to improve and same with earning capacity. In addition to all these, government may also use the instrumentality of the loan to push students towards some courses that are relevant to the nation’s manpower requirement by giving priority to students who go in for those courses.

- Strengthening Scholarship Schemes

Scholarship awards, whether need-based or merit-based, represent another opportunity for talented students to pay for university education. It is interesting to note that while the Federal Government and some state governments award scholarships every year, they are mostly for candidates to study abroad. Under the Bilateral Education Agreement, the Federal Ministry of Education awards scholarships to Nigerian students to study in countries such as Russia, Morocco, Hungary, Egypt, Cuba, Macedonia and Japan. Sending students to study abroad has also become a pet policy of some state governments in recent years. Government agencies like the Petroleum Trust Development Fund (PTDF) also award annual study-abroad scholarships, up to $30,000 for a student. A 2022 report says PTDF has awarded 9,659 such scholarships since 200214.

It is possible to argue that governments and government agencies prefer to award foreign scholarships because Nigerian universities do not charge fees. The rise in the number of fee-paying private universities in recent years would however put a question mark on that argument. Most scholarships available to study in public universities in Nigeria are awarded by private companies in the country. These limited scholarships are mostly for the upkeep of the students. Introducing tuition payment is likely to direct some of these scholarships into Nigerian universities and help students to pay.

- Expanding Funding through Endowments & Alumni Donations

Endowment is another great opportunity for universities to expand their pool of funds. Just as government alone cannot provide all the money that universities need to be truly competitive in a global sense, tuition payment would also not be the silver bullet. The universities must constantly seek means to expand their funding based. This is why the modern university administrator is more of a fund raiser than anything else. But the current system does not encourage the goal-getting attitude that is required to attract the right support outside government.

Some of our public universities have endowments already, but they are too paltry for the scale of the challenge. Alumni represent a great source of endowments to universities. Each university needs to bring their alumni closer and give them real incentives to contribute to the funding of their alma maters.

Many universities have alumni who have gone on to become successful businessmen and women, and even state governors and ministers. Many are even setting up their own universities. The universities need to be more deliberate in tapping into this opportunity.

- Instituting Work-Study Programmes

Looking at the unemployment statistics, it would be tempting to dismiss this as an option. But work-study provides additional option for indigent students. And they don’t have to seek employment outside the universities. Some reports indicate that many of the universities have up to four times the number of their academic staff as non-academic staff, mostly doing the work that students can do and get paid for.

The employment office can keep a register of students who need such jobs and give them priority as vacancies are available. Also, some of the students can serve as research and teaching assistants to lecturers or serve as library assistants. As done in many countries abroad, the number of hours that students can work per week should be limited so that work will not interfere with their study.

- Develop a New Framework for TETFUND’s Allocations

The Tertiary Education Trust Fund was established in 1993 to manage the 2% education tax payable by companies registered in Nigeria and to disburse same to tertiary institutions in the country for the purpose of providing or maintaining physical infrastructure for teaching and learning, for instructional material and equipment, research and publications as well as academic staff training and development15.

Although the TETFUND was intended to provide intervention funds to support the universities in the areas listed above, it has more or less become the only source of funding available to the universities to carry out those activities. Apart from the grants uniformly awarded to universities annually, some universities may still get additional grants depending on the vice-chancellor’s political connections or capacity to lobby.

There is no evidence that allocations from TETFUND follow any objective parameters other than the Fund’s own discretion or proposals submitted by the universities themselves based on their respective needs. Moreover, giving the same amount to all universities regardless of their performance in the core business of teaching and research does not encourage productivity or accountability. Therefore, a new National Framework for Tertiary Education Funding needs to be developed that will set objective parameters for allocation of funds.

This new framework should ensure that institutions are funded based on verified outputs in teaching, research and community service. While the details of this funding framework will still need to be worked out, the main objective is to ensure that funding is made based on output, rather than input requirements. Because the parameters for allocation of funds under the new framework will also be objective and pre-defined, it would bring about greater equity and transparency, while providing real incentives for each institution to respond to the national development needs in manpower development, research, and community service.

A framework that funds the entire higher education system as a single system will also improve accountability and limit the chance for duplication. Perhaps more importantly, because institutions would be required under the new framework to show evidence of change in governance, operations and productivity, funding will then serve as an important lever in driving the desired reform. The idea of financial autonomy to the universities would also be better served because once a university is able to win the grant under the new framework, it would also be at liberty to decide how to spend it to better position itself for even more grants in the future.

- Re-prioritising Quality Assurance

Conversations about improving the quality of university education or education generally usually focus strongly on the issue of funding. As has been noted however, a university is like a factory. If the factory is not producing the goods, simply throwing in more money or recruiting more staff will not change its fortune. To proceed with the same analogy, a factory that is designed to produce sheets of paper cannot be used to produce roofing sheets without undergoing a major redesign.

Generally, people go to university to increase their earning power and for social mobility. But like Kosack noted, the investment value of education is a function of three conditions: the education’s quality; scarcity; and the level of the country’s economic development.”16. Nigeria has doubled admission spaces in the last two decades or so, yet a significant majority of those who apply for university admission each year are unable to get in. Rapid expansion of private universities in recent years has not helped much, as most students are unable afford the fees they charge. While there are 79 private universities in the country, they account for only 6% of the undergraduate students enrolled in Nigerian universities.

Of the remaining undergraduates, 29%are in the 48 state universities while the remaining 65% percent are in 43 federal universities. Available reports indicate that only one in four applicants (or 25% of applicants)is able to secure admission. This has pressured the government to continue to expand access by granting licenses to private universities and setting up new ones of her own.

In 2011 alone, the government set up nine new federal universities. It is axiomatic that wherever enrolment expands too quickly, the first casualty is quality. Expanding access without paying corresponding attention to factors that actually determine quality of teaching and learning will ultimately devalue education. It is no surprise therefore that one of ASUU’s demands is that government should stop the proliferation of universities. Related to the issue of quality is also the issue of relevance both in terms of curriculum content and in terms of course preferred by students relative to the needs of the employment market and the nation’s manpower needs.

The Association of African Universities has identified weakness in curricula and how they are delivered as major factors in explaining the declining quality of graduates in Africa: “The orientation of curricula needs to shift away from producing theoretical elites and administrators to produce doers and entrepreneurs who are transformational wherever they find themselves.

Due to poor remuneration and poor facilities, African HEIs are not competitive in attracting and retaining top instructors.”17 In addition to this is the question of what the students are applying to study and how these courses will help their prospect of getting a job or contributing in areas that the country needs their expertise. In 2019, while 1,874 graduated in Medicine and 923 in Computer Engineering, 10,261 graduated in Accounting, and 6,239 in Political Science in the same year.

Other reports also show that Education and Agriculture are the only two courses for which universities are not receiving enough applications, yet these are areas of critical manpower needs for the country.18 The issue of curriculum is also related to that of governance. Over-centralisation of the university system has created a sense of uniformity that has robbed every university the chance to develop a unique character of its own. Almost every university offers the same menu of courses without regards to the needs of its local environment or its own capabilities.

As stated earlier, higher education system in Nigeria must be situated within a national human resource development strategy, which in turn must derive from a broader national development plan. Therefore, transforming the public universities in Nigeria will not be a job for the minister or the Ministry of Education alone. The Ministry of National Planning, the Ministry of Labour and Productivity and the Organised Private Sector (OPS) must work closely together. But the process has to be led by the President of the country or someone who has his convening authority to drive the process.

The 2023 webometrics ranking of African universities includes less than 10 Nigerian universities in the top 100. While these rankings may be taken as fair indicators of our universities’ standing within the parameters being measured either in a global or regional context, they are not sufficient in measuring our higher education institutions’ responsiveness to the national development needs. We need a new system of evaluation and quality assurance that is semi-autonomous and has a strong private sector orientation.

It is important for the private sector to play a leading role in quality assurance because they are the major off takers of what the universities produce as students or as research. Acting Director of the Innovation and Technology Management Office of the University of Lagos, Abiodun Gbenga-Ilorin, recently stated that 13,282 research papers were published in Nigeria in 2020, which ranks the country 50th in the world in the number of research papers published that year. However, of all these, only 300, about 2.2 percent has led to successful innovations. Working closely with the industries will ensure that research focus becomes more demand- and solution-driven, plus the added benefit of attracting good funding19.

Summary of Recommendations

- Federal Government needs to step back. Less government is best for universities. Government should grant full autonomy to its public universities, and allow each university to develop its own identity and grow at its own pace.

- National Universities Commission Act (1974) should be amended to release its stranglehold of NUC on the universities and assign it a coordinating and monitoring role rather than a directive or prescriptive role.

- In keeping with the principle of autonomy, government should cede its role as employers of university lecturers to each university. This will empower the universities to negotiate terms and conditions of service with their respective employees in line with their local reality and the value expected of each lecturer.

- A realistic annual cost for each student should be determined and the universities should be funded by government based on the number of students rather than personnel or administrative needs of the university.

- Universities should be allowed to charge tuition fees within the parameters set by government, but the Education Bank needs to be established to offer federal government-backed loans to students who may require them.

- Government and institutional scholarship awards are another opportunity for talented but indigent students to pay tuition. Most government scholarships now are targeted at students studying abroad. This should be reversed.

- Work-study also presents another option for indigent students. Most of the work currently being done by non-academic staff and even contract staff in the universities can be done by students.

- Endowment funds are a major way for universities to expand their pool of funds. Currently, the universities are not tapping into it as much as they should do. They need to bring their alumni closer and give them incentives to contribute to their university endowment programmes and to establish scholarship schemes and give back in other ways.

- A new framework for tertiary education funding needs to be developed that will set objective parameters for allocation of funds from the TETFUND based on verified outputs in teaching, research and community service.

- A semi-autonomous National Higher Education Quality Assurance Agency (NHEQAA) needs to be established to monitor the quality of teaching and research in the universities, and evaluate them in terms of their responsiveness to the nation’s manpower requirement and economic development plan.

*Abudullahi, an education enthusiast, was Commissioner for Education in Kwara State and Minister for Youth Development and Sports.

Footnotes

[1]IBRD/WB. (2003), Directions in Development - Lifelong Learning in the Global Knowledge Economy: Challenges for Developing Countries, World Bank, Washington DC; and Kosack S. (2020). The Education of Nations: How Political Organisation of the Poor, Not Democracy, Led Governments to Invest in Mass Education; Oxford University Press, New York.

[2] In projecting for 15 years, I adopt the cycle for the United Nations Millenium/Sustainable Development Goals.

[3] National Universities Commission Act, 1974.

[4] Pritchett L., (2013). The Rebirth of Education; Centre for Global Development, Washington DC.