By Adebayo Ahmed | Jobs are one of the foundations for a stable society and key to improvements in quality of life. Unfortunately, unemployment is one of Nigeria’s major challenges today. Beyond the negative impact on human welfare, unemployment is gravely implicated in Nigeria’s other pressing challenges, especially low productivity, poverty and insecurity. It needs to be tackled aggressively and comprehensively, not in the current tokenistic and uncoordinated fashion.

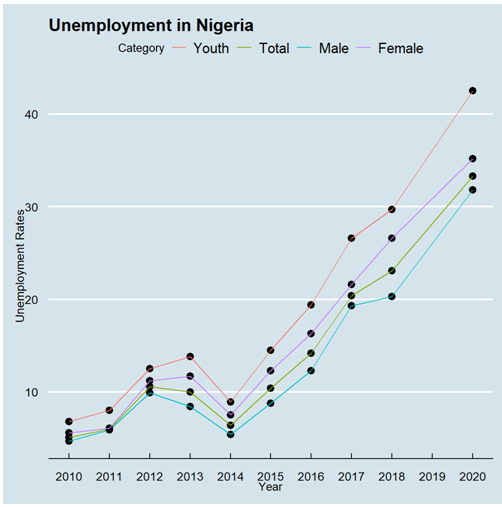

Fig 1: Unemployment Rates. Source: NBS

In the last decade Nigeria has struggled to create enough jobs to meet up with the constant flow of people entering working age. Since 2010 the unemployment rate has been on an upward trajectory rising from 5.1% in 2010 to the last pre-covid estimate of 23.1% in 2018, with the situation worse for women. Unemployment rate rose to 33.3% during COVID, combined with a much-reduced labour force participation rate. There has been little official information since. Although the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) claims to be working on an improved methodology for measuring unemployment, all we can say at this point is that unemployment is likely still high and at an undesirable level. The situation has been particularly worse for young people who, as at 2020, faced an unemployment rate of over 40%. There is little doubt that this rising unemployment is linked to increasing restfulness and disenchantment among the youth.

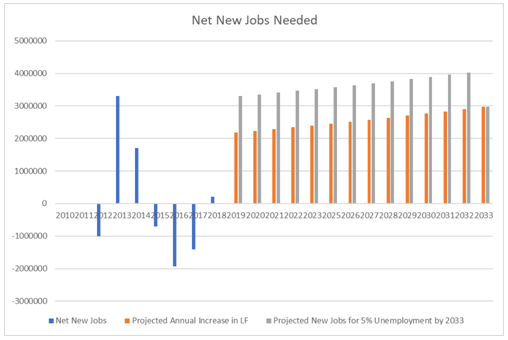

Fig 2: Net new jobs created and needed. Source: NBS, Author’s Calculations.

Given that the population, and hence the labour force, keeps growing, the challenge of reducing unemployment is therefore all about creating more new jobs than there are people entering the labour force. At the very least, to keep unemployment from rising, enough net new jobs need to be created to at least employ the majority of net new entrants to the labour market. What does this mean in the Nigerian context? Based on a labour force of about 90 million1 prior to COVID in 2018, about 2.5 million net new people enter the labour force every year. Which means the economy would have to create at least 2.5 million new jobs a year on average just to keep the number of the unemployed from rising. If we wanted to get the unemployment rate to a healthier five percent by 2033, and we assumed that the labour force grew at the same rate as population growth, then by our calculations, we would need to be creating at least 3.6 million net new jobs a year2. Given that between 2010 and 2018 we only created on average 21,757 net new full-time jobs a year then you can see clearly that we have a problem3. In fact, as shown in Figure 2, 2013 is the only year in the last decade when we actually produced over three million net new jobs.

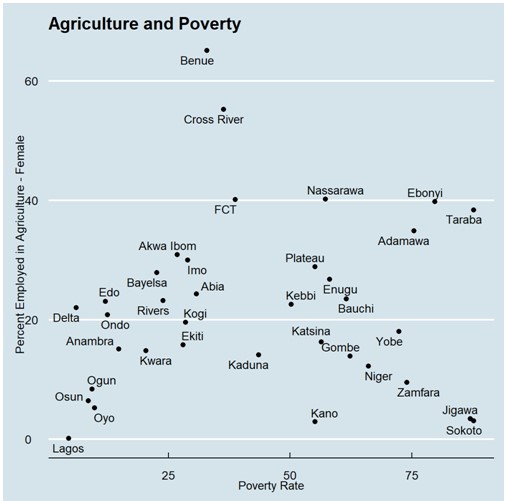

Fig 3: Employment in Agriculture vs Poverty Rates across states (Male and Female).

Source: NBS Living Standards Survey 2018.

If we add the caveat that the jobs created have to be good enough to allow people have a meaningful quality of life, then the challenge is even more difficult. One of the features of current employment, especially in subsistence agriculture, is that some of the jobs do not result in enough income to actually lift the employed persons out of poverty. As observed in Figure 3 above, some of the states with the largest employment in agriculture also happen to be the states with the highest poverty rates. Many of these people are employed but are still living in poverty despite their employment. For example, although Sokoto State had an unemployment rate of 14.3% in 20184, majority of the people were employed in (presumably) subsistence agriculture (51% of males and 3% of females). The implication being that over 87% of households were still living in poverty. In essence, it is not just jobs that are needed but decent jobs.

Limits of current approaches

The current approaches by government to tackling unemployment, while sometimes having merit, have failed to resolve the problem. This is largely because the majority of the approaches cannot reach the scale of what is required.

The first of the common approaches is direct government employment. This is particularly popular at the state and local government level, even if the Federal Government is not left out. Although it is easy to argue that the country needs more police personnel, more doctors, and more teachers, it is clear that government employment alone cannot solve the unemployment challenge. It is almost unfathomable to imagine the federal, state, and local governments combined being able to employ anywhere close to three million workers each year. This is even before you take into account their financial constraints. In fact, according to some reports, the entire Federal Government only employed about 720,000 people as at 20205. The ILO estimates that there were only about 2.12 million people employed in the public sector in Nigeria in 2020. Given the scale of the challenge, it is unsurprising that government employment has not worked in resolving the challenges.

Fig 4: Q3 2018 Unemployment by Educational Category. Source: NBS

A second common approach is the skills-acquisition driven approach. The summary of this approach is that if you teach people some skills, such as carpentry or tailoring, then that should automatically result in employment. For instance, a cursory look at the activities of the National Directorate of Employment (NDE) shows that most of its programmes are essentially skills acquisition programmes. However, unfortunately, in reality skills do not necessarily mean jobs. For instance, in 2018 the unemployment rate for people with post-secondary education at 29.8% was higher than for people with no education at 21.8%. Similarly, as is clear in Figure 4

above, people with only primary education had a lower unemployment rate than people with NCE/OND/Nursing certificates even though they presumably have more skills. Although there are issues such as skills mismatch and selectivity in employment, and there is still significant room for certification for specific skills, it does signify that more skills alone will not necessarily solve the unemployment challenge.

The third, and more recent approach is that of social investment or social transfers as signified by the expansion of programmes such as trader-moni or other direct cash support schemes popular at state and local government level. As with the case with direct government employment, the scale of the challenge means that this is unlikely to be a sustainable approach. According to the NBS6, only between 10,000 and 20,000 thousand were enrolled in the governments N-Power programme in each state as at 2018. The FG stated that it planned to raise the total number of beneficiaries to one million in 2020. The GEEP programmes have similar statistics. Although you can argue about the merits or demerits of such programmes, what is clear is they are not creating, and probably cannot create, the 3.6 million net new jobs a year to tackle Nigeria’s unemployment challenge.

Prescriptions / Recommendations

In thinking of a coherent strategy to tackle the unemployment challenge, we need to take a step back and understand what exactly jobs are. Jobs are essentially the contribution of individuals to economic activity. Which means if you want to see faster job growth then you must have faster economic growth. However, as we learned during the growth episodes in Nigeria in the early 2000s, growth alone does not imply jobs. There can be jobless growth and job-led growth. Specifically, what we need is growth in labour-intensive sectors.

For instance, growth in petrochemical refining or car assembly is unlikely to provide as much jobs per unit of output compared to growth in the more labour-intensive textiles sector. Even within the textile value chain, growth in the relatively capital-intensive part of the chain that converts cotton into fabric, is unlikely to create as many jobs per unit of output as the more labour-intensive part that converts fabrics into clothing. There needs to be a specific focus on engineering sustainable growth in these labour-intensive segments of various value chains. Given the scale required—3.6 million net new jobs a year—the output of this engineered growth will likely need to be targeted at markets much larger than Nigeria’s.

In summary, on a macro level the most likely path to job creation in Nigeria at the scale required, is to engineer growth in labour-intensive portions of value chains for export to large markets. What does this mean in terms of specific policy actions?

From a broader economy-wide perspective, it means:

- Resolving broader macro-economic challenges that limit growth across the board. This includes resolving the dysfunction of multiple rates in the foreign exchange market, and re-focusing the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) on its mandate of keeping inflation at optimal levels.

- Targeted infrastructure spending in particular areas that increase the competitiveness of Nigeria’s exports. This would include electricity, transport, and telecommunications investments in export processing zones. For instance, India’s new foreign trade policy 20237 designated four “towns of export excellence” that will get priority access to export schemes and investments.

- Developing and implementing an export-driven trade policy for labour-intensive value addition for export sectors. This could include fast-tracking implementation modalities for participating in the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), fast-tracking trade agreements that grant Nigerian export access into large markets, and reducing tariffs completely or introducing transparent reimbursement schemes for imports of intermediary goods for value addition.

- Developing a strategy to utilise our large diaspora network as well as our network of embassies and consulates to get Nigerian products into markets around the world.

- Re-organising our technical and non-academic learning protocols to improve on specific skills in areas critical for improvements in competitiveness of targeted sectors. This could include trade schools aimed at providing necessary skills for particular sectors. For instance, if the garment sector is a targeted sector it would include starting up or improving on technical schools and certification for fabric cutting or clothing design software.

- Developing and implementing a strategy to reduce the costs of logistics, both financial and non-financial. This could include things like “trusted firm” schemes that allow customs and security procedures take place inland, at dry-land ports for instance, to by-pass time-consuming procedures at official ports.

- Investing in certification and export processes training in partnership with targeted destination countries to ease the cost of accessing external markets, specifically for SMEs that do not have the financial clout to do this on their own. As has been argued by some economists, SMEs tend to employ more people per output produced. Hence, ensuring SMEs participate in an export push can amplify the scale of job creation.

To improve the decency and capacity of agriculture jobs to provide a minimum income and quality of life, this will mean:

- Developing and implementing a productivity growth strategy for agriculture that will target improvement in yields for subsistence farmers. This will include strategies for improved seed varieties, improved crop choice, irrigation infrastructure, crop-specific weather and market information, crop insurance and social protection etc..

- Developing and implementing a market development and financial innovation strategy for agriculture to ensure that crops have access to markets and off-takers, and predictable and flexible revenue streams.

Finally, to take advantage of the growing global trends in remote work especially in ICT and other export services, this will mean:

- Fast tracking the implementation of the broadband plan to improve the competitiveness of Nigeria’s remote workers.

- Developing a fair, transparent, and competitive taxation policy for remote workers that reduces their incentives to emigrate to tax havens and that incentivizes other skilled workers to opt for Nigeria.

- Working with states to develop livable safe spaces that incentivize skilled workers to remain in Nigeria.

Conclusion

The size of the Nigerian population and the scale of the unemployment challenge implies that piecemeal and uncoordinated approaches are unlikely to make a significant impact. If Nigeria desires to get unemployment down to 5% by 2033, it needs to create 3.6 million jobs a year. To achieve this, it needs a scalable strategy. Given that jobs are simply part of the process of generating economic activity, then Nigeria needs to engineer growth in labour-intensive sectors in general, and labour-intensive parts of value chains in particular.

[1] National Bureau of Statistics Labour Force Survey Q3 2018

[2] A labour force growth rate of 2.41% implies that by 2033 the labour force would have about 126m people. This means to have 5% unemployment then about 120m people need to be employed. Which in turn implies that between 2018 and 2033, about 54m new jobs need to be created. This amounts to about 3.6m net new jobs a year on average.

[3] National Bureau of Statistics Labour Force Surveys 2010 - 2018

[4] NBS – Q3 2018 Unemployment by States

[5]https://leadership.ng/ippis-fg-trims-civil-servants-to-720000/

[6] NBS 2020 Social Statistics in Nigeria

[7] https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1912572