- Details

- By Agora Policy

- Policy Memo

- Hits: 465

By Bolaji Abdullahi | Nigeria’s return to democratic rule in 1999 coincided with the end of the first decade of a global commitment to the goal of Education for All (EFA) and the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), focused on achieving universal basic education, especially in the developing countries, as one of its core objectives.

However, while many countries still struggle to achieve the goal of universal education, a strong consensus has emerged over the years that although basic education is important, no country has achieved growth on the back of mass literacy alone.

The compelling argument for greater investment in university education, relative to other levels of education, flows from the strong evidence that better graduates have greater positive impacts on economic growth as well as the realisation that the 21st Century global knowledge economy requires more than literacy.1 The transformation of our public university system, where 94% of the undergraduates within Nigeria are enrolled, should therefore be integral to our vision of economic growth and competitiveness.

The promise of national development must reflect in our commitment to transforming the public university system to make it more efficient and able to meet the skills, knowledge and research needs of our country now and in the future. In seeking to realign our public university system with our national development objectives, we must ask four critical questions:

- What are our development goals over the next 15 years?2

- What human resources would we need to achieve these goals?

- How many of our citizens of university-going age would we require to have degree-level qualifications in the identified areas of need within the same period?

- What research priorities do we need to pursue and promote in order to meet these goals?

Attempts to answer these questions will highlight major problems in our current attitude to public university education which in turn has conditioned how we structure, operate and fund the system. The endemic corruption, inefficiency, ineffectiveness, inequity and lack of accountability that characterise the system merely thrive on a fundamental failure that cannot be addressed by interventions that merely target any of the symptoms in isolation. What we require is a system-wide reform that addresses the three critical elements of governance, funding, and quality assurance based on a rethinking of the entire public university education itself as a driver of national development objectives.

-

Rethinking the Governance of Public Universities

The central issue in governance is that of efficiency and service delivery. What kind of governance regime is best suited for the kind of services that the public universities are expected to provide? At the heart of this question in Nigeria is the issue of autonomy: the degree to which each university has the freedom to operate independent of the government authorities that set them up and fund them.

In Nigeria, universities are governed by the National Universities Commission (NUC), whose establishment Act of 1974 gives it controlling power over the university education system, including what departments or academic units they run and what they teach; what funding they receive and how; what personnel they hire and the conditions of service attached to such personnel; what their research needs are; and “carry[ing] out such other activities as are conducive to the discharge of its functions under this Act3.” Many university administrators and lecturers regard the NUC as a major impediment to innovation and creativity in the universities.

Global trends also suggest that less government is better for universities and that universities function best when they are self-governing. Lant Pritchett, a professor at Harvard University, used the spider and the starfish to illustrate two kinds of systems. The spider system is that in which all organs and parts of the body are centrally controlled, while the starfish allows for a level of control but grants freedom to each of the limbs to operate with significant autonomy. A pure spider system, Pritchett says, pulls responsibility for all functions to itself, especially through financing; whereas a starfish system creates local operation which,

“Pulls apart all of the many functions and activities and allocate those across the system such that the local component of the system provides a constant stream of innovation and new ideas and can use the local nature of the operation of the system for thick accountability…while the national level provides a framework for standards and monitoring and evaluation performance4”.

The starfish approach will fit squarely within a system of embedded autonomy which allows the university the flexibility to explore and establish local and international relationships and partnerships while government involvement is scaled back to quality assurance and monitoring compliance with national regulations. Another major advantage of the starfish system is that by granting autonomy to the local components, it also ensures that a problem with one of the components does not cripple the entire system.

By granting autonomy to each of the universities to negotiate contract terms with its staff based on its unique capabilities and local conditions, the government would have addressed the problem posed by the principle of collective bargaining which has turned the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) into a disruptive force over the years. Of the eight identified issues that have formed the basis for ASUU’s perennial strikes, five are directly related to issues of conditions of service and remunerations5.

Granting autonomy to the universities along this line will not necessarily save the government money, but it will achieve three things. One, it will bring stability to the university system; two, it will ensure that the lecturers are competitively and equitably remunerated; and three, it will enable the government to focus on her quality assurance functions as an objective arbiter.

The argument for more equitable remuneration of lecturers is central to attracting and retaining the right calibre of lecturers and professors. The current system that pays lecturers in different contexts and with different quality of outputs the same salary just because they are on the same “salary scale” is wrongheaded and suboptimal. However, this can only be corrected if each university is at liberty to negotiate salaries and other benefits with its lecturers.

University lecturers should be employees of their universities not those of the Federal Government or the state go vernments. Essentially, what we require is a system that fosters high-level competition for resources and even for students. Under the current governance system, the universities lack the incentive to do anything differently. Neither the funding they get nor the students that come to them depends on the quality of what they offer to students either in terms of learning or living experience or the quality of their research outputs.

Autonomy will create the condition for each university to develop at its own pace, based on real accomplishments in research, in teaching and in their contributions to national development goals. It is interesting to note that “university autonomy and academic freedom” has been one of ASUU’s key demands. Their desire is to free the universities from what they consider as the stranglehold of the NUC. The obvious implication of this, however, is that the NUC must undergo its own reform to enable it repurpose itself for its coordinating and monitoring role in a new governance system.

2. Changing How Public Universities are Funded

In respect of funding, two factors need to be considered. Effectiveness: are they being adequately funded? Efficiency: are the funds being spent on factors that are directly relevant to delivering the best results, especially in the core task of teaching, learning and research? The current funding system does not meet either of the criteria. The chief source of funding for public universities in Nigeria is the government, whose intervention however accounts for only about 44% to 60% of what is required to run a university effectively6. This means that at any given time, the funding deficit is between 40% to 56%.

Table 1: Allocations to Federal Universities in the 2023 Budget

Source: Budget Office of the Federation

Table 2: 2023 Allocations to Federal Universities: Percentage of allocation to personnel and overheads

Source: Budget Office of the Federation

Table 2 indicates that between 86% and 96% of the federal allocations of these four universities goes to personnel cost alone. This leaves a range of 0.7% to 1.4% and 2.2% to 7.2% for overhead and capital respectively. What this means in essence is that our federal universities are existing mainly to pay salaries, with hardly much left for the other operational costs and for provision and maintenance of infrastructure for teaching, learning and research. Funding effectively and efficiently would require a major paradigm shift in how we view public university education generally and how we fund it.

If we take the budgetary allocations to the universities as standing in lieu of tuition, this should be regarded as subsidy. However, as Table 2 has shown, what the government has done over the years is to subsidise personnel cost of the universities, rather than the students who should enjoy the subsidy.

A major step-change that is required here is to target the subsidy payments around students’ enrolments rather than the administration of the university. What this does is to place the students at the center of the university planning, with all other expenditures, including personnel, overheads and physical development, now revolving around the students and their needs. This also ensures an objective parameter for allocation of funding, one that is focused on output rather than the current input-based approach. Running a university costs a lot of money.

Costs are incurred almost on a daily basis. One Vice Chancellor reported spending about N40million monthly on diesel alone to keep the generators running, this is in addition to the cost of the main electricity supply. The university therefore spend up to N100million on power supply alone in a given month. Infrastructure and vehicles maintenance, fueling of vehicles, re-agents and other consumables for the laboratories, sporting activities, all these are covered under the overhead costs, which are released to the universities on a month-by-month basis.

However, interaction with several university heads reveals that while the budget for personnel is released 100%, they hardly get more than 50%of overheads allocation in a given year7. However, even if all the overhead allocation is released, it is hard to imagine how it could meet the monthly cost of running the university. For example, the University of Nigeria Nsukka (UNN) with an overhead allocation of about N203 million in its 2023 budget has a population of 36,000 students. To start with, it means that UNN has an allocation of N16.9 million per month for overhead. But more interestingly, it means that, minus personnel cost, the university has only N5,638available in a year as running cost for per student.

Even if this amount is added to the fees charged by the university in a year, the total available per students will be about N67,000 or $145. This applies to all federal universities in Nigeria. The Fallacy of Tuition-Free Education The two organised ‘vital constituencies’ for government in producing education are the students and the lecturers. The two constituencies appear to want the same thing: university education that is accessible to all who can meet the entry requirement, that is of high quality and that is free of charge.

Although this is more like a pie in the sky, government has continued to give the impression that it is possible to achieve. This has resulted in a lose-lose situation for everyone involved. Government’s best funding efforts continue to run short, the vital constituencies are permanently disgruntled, and the system continues its steady decline because government has been funding the administration of the institutions rather than education itself.

Table 3: Fees charged by some public universities in Nigeria8

In contrast, Table 4 shows the fees charged by some private universities in the current year.

Table 4: 2023 First Year fees for some private universities in Nigeria9

It is possible to argue that private universities run on a business model and will not operate at a loss. Nevertheless, the fees they charge may provide useful insights for determining what might be a realistic cost of providing university education in Nigeria. It is interesting to note that American University of Nigeria in Yola actually calculates its fees per credit units offered by the student10.

Even if we account for profitability, it is difficult to understand how University of Ibadan can reasonably charge a maximum fee of N36,800 in a session for a course that AUN, Yola charges more than twice the same amount to teach a single credit. Best practice is to fund university based on the needs of students. Money must be made to follow the students.

We need to determine what is required to deliver university education to each student, do a realistic costing and pay the universities accordingly or arrive at a cost-sharing arrangement, with government bearing most of the costs. It is understandable why government may want to persist on the outmoded policy of zero tuition, but no one is helped by it, not least the students who are mostly being rolled through the university with no prospect of real employment because they have not had the opportunity to acquire real skills.

Government needs to allow introduction of cost-reflective tuition or should pay the university full equivalent of what they would ordinarily charge as tuition or provide alternatives that guarantee realistic funding for the universities. Like Kosack argued “in the absence of a well-functioning private education market, where most consumers are unable to afford education without subsidy, there are only two options: government continues to pay subsidy or lower the fee to make it available to everyone11.”Kosack’s assumption is that there are fees to lower.

But what happens where there are no fees at all, and government cannot pay enough? In the current fiscal climate, it is unlikely that government can afford to give the universities all the money they need to function effectively. Government therefore needs to invite parents to shoulder more of the financial responsibility. If it is clearly defined as a means of improving quality, which will enhance the employability of the students upon graduation, it would not be a totally strange proposition.

Afterall, as parents lose confidence in the public primary and secondary schools, they voted for fee-paying private schools. It is indeed curious that parents who were able to pay fees running into hundreds of thousands for private basic education would expect to pay next to nothing for university education. Below are some options that can be explored to improve the pool of funding for our public universities and ensure that students from poor homes are not denied access to university education.

- Guaranteed Loan through the Education Bank

The issue of a federally-backed Education Bank has been in the works for about three decades. Now is the time to give it real traction in the context of the funding reform. It is a great opportunity that the National Assembly as well as some civil society actors have backed the idea over the years12. Once again, the only voice of dissent is ASUU, whose president declared in 2022 that “ASUU will never support the issue of Education Bank because the poor will not benefit from it.”13

It is not clear from this statement whether ASUU is opposed to the idea of students’ loan because it thinks the scheme would constitute a debt burden to the students or because the union fears that the loans might not be awarded to intended beneficiaries. Whatever the case, concerns should be addressed and the idea of an Education Bank must be framed as part of the efforts to improve quality of education generally (including to ensure that the public universities are well funded and the lecturers can be well paid) and as a means to support indigent but talented students who need university education for career progression.

Affordable loans, with repayment tied to salaries earned upon graduation will ensure that children from poor homes are not excluded from university education because their parents are too poor to pay. One major reason the idea of a students’ loan scheme may not be attractive, especially to a government seeking to shift costs, is that the risk of people defaulting is high. Education is a bad collateral.

A bank can recover a house from a defaulting customer, but education cannot be recovered from a customer who fails to pay for the obvious reason that she is not able to get a job after graduation or because she has simply relocated to another country, leaving no contact address. There is thus the risk that government might still end up paying for defaulters, except adequate risk-mitigating strategies are put in place. In the context of a full subsidy, the alternative is for the government to give out scholarship vouchers to students which would stand as guaranteed promissory notes that the universities could redeem with the government.

If the government is able to redeem the vouchers in full and on time, it would have ensured that the universities get paid the agreed amount for each student. But this is unlikely to happen. It is important to emphasise that the conversation around an Education Bank is in the context of the need to introduce tuition payment in the university, which has become inevitable as the only realistic and sustainable pathway to effective funding of the universities.

Even in the face of high risk of default, there are other benefits to the system in the idea of a student incurring a debt to fund her education. It turns the parents and the students into active financial stakeholders and gives them a skin in the game. Perhaps, the most important effect is that it is likely to engender a new attitude towards learning and even teaching.

As the indebted students begin to demand value for money, horizontal accountability will be strengthened and quality is likely to improve generally. As quality of graduates improve, employability is likely to improve and same with earning capacity. In addition to all these, government may also use the instrumentality of the loan to push students towards some courses that are relevant to the nation’s manpower requirement by giving priority to students who go in for those courses.

- Strengthening Scholarship Schemes

Scholarship awards, whether need-based or merit-based, represent another opportunity for talented students to pay for university education. It is interesting to note that while the Federal Government and some state governments award scholarships every year, they are mostly for candidates to study abroad. Under the Bilateral Education Agreement, the Federal Ministry of Education awards scholarships to Nigerian students to study in countries such as Russia, Morocco, Hungary, Egypt, Cuba, Macedonia and Japan. Sending students to study abroad has also become a pet policy of some state governments in recent years. Government agencies like the Petroleum Trust Development Fund (PTDF) also award annual study-abroad scholarships, up to $30,000 for a student. A 2022 report says PTDF has awarded 9,659 such scholarships since 200214.

It is possible to argue that governments and government agencies prefer to award foreign scholarships because Nigerian universities do not charge fees. The rise in the number of fee-paying private universities in recent years would however put a question mark on that argument. Most scholarships available to study in public universities in Nigeria are awarded by private companies in the country. These limited scholarships are mostly for the upkeep of the students. Introducing tuition payment is likely to direct some of these scholarships into Nigerian universities and help students to pay.

- Expanding Funding through Endowments & Alumni Donations

Endowment is another great opportunity for universities to expand their pool of funds. Just as government alone cannot provide all the money that universities need to be truly competitive in a global sense, tuition payment would also not be the silver bullet. The universities must constantly seek means to expand their funding based. This is why the modern university administrator is more of a fund raiser than anything else. But the current system does not encourage the goal-getting attitude that is required to attract the right support outside government.

Some of our public universities have endowments already, but they are too paltry for the scale of the challenge. Alumni represent a great source of endowments to universities. Each university needs to bring their alumni closer and give them real incentives to contribute to the funding of their alma maters.

Many universities have alumni who have gone on to become successful businessmen and women, and even state governors and ministers. Many are even setting up their own universities. The universities need to be more deliberate in tapping into this opportunity.

- Instituting Work-Study Programmes

Looking at the unemployment statistics, it would be tempting to dismiss this as an option. But work-study provides additional option for indigent students. And they don’t have to seek employment outside the universities. Some reports indicate that many of the universities have up to four times the number of their academic staff as non-academic staff, mostly doing the work that students can do and get paid for.

The employment office can keep a register of students who need such jobs and give them priority as vacancies are available. Also, some of the students can serve as research and teaching assistants to lecturers or serve as library assistants. As done in many countries abroad, the number of hours that students can work per week should be limited so that work will not interfere with their study.

- Develop a New Framework for TETFUND’s Allocations

The Tertiary Education Trust Fund was established in 1993 to manage the 2% education tax payable by companies registered in Nigeria and to disburse same to tertiary institutions in the country for the purpose of providing or maintaining physical infrastructure for teaching and learning, for instructional material and equipment, research and publications as well as academic staff training and development15.

Although the TETFUND was intended to provide intervention funds to support the universities in the areas listed above, it has more or less become the only source of funding available to the universities to carry out those activities. Apart from the grants uniformly awarded to universities annually, some universities may still get additional grants depending on the vice-chancellor’s political connections or capacity to lobby.

There is no evidence that allocations from TETFUND follow any objective parameters other than the Fund’s own discretion or proposals submitted by the universities themselves based on their respective needs. Moreover, giving the same amount to all universities regardless of their performance in the core business of teaching and research does not encourage productivity or accountability. Therefore, a new National Framework for Tertiary Education Funding needs to be developed that will set objective parameters for allocation of funds.

This new framework should ensure that institutions are funded based on verified outputs in teaching, research and community service. While the details of this funding framework will still need to be worked out, the main objective is to ensure that funding is made based on output, rather than input requirements. Because the parameters for allocation of funds under the new framework will also be objective and pre-defined, it would bring about greater equity and transparency, while providing real incentives for each institution to respond to the national development needs in manpower development, research, and community service.

A framework that funds the entire higher education system as a single system will also improve accountability and limit the chance for duplication. Perhaps more importantly, because institutions would be required under the new framework to show evidence of change in governance, operations and productivity, funding will then serve as an important lever in driving the desired reform. The idea of financial autonomy to the universities would also be better served because once a university is able to win the grant under the new framework, it would also be at liberty to decide how to spend it to better position itself for even more grants in the future.

- Re-prioritising Quality Assurance

Conversations about improving the quality of university education or education generally usually focus strongly on the issue of funding. As has been noted however, a university is like a factory. If the factory is not producing the goods, simply throwing in more money or recruiting more staff will not change its fortune. To proceed with the same analogy, a factory that is designed to produce sheets of paper cannot be used to produce roofing sheets without undergoing a major redesign.

Generally, people go to university to increase their earning power and for social mobility. But like Kosack noted, the investment value of education is a function of three conditions: the education’s quality; scarcity; and the level of the country’s economic development.”16. Nigeria has doubled admission spaces in the last two decades or so, yet a significant majority of those who apply for university admission each year are unable to get in. Rapid expansion of private universities in recent years has not helped much, as most students are unable afford the fees they charge. While there are 79 private universities in the country, they account for only 6% of the undergraduate students enrolled in Nigerian universities.

Of the remaining undergraduates, 29%are in the 48 state universities while the remaining 65% percent are in 43 federal universities. Available reports indicate that only one in four applicants (or 25% of applicants)is able to secure admission. This has pressured the government to continue to expand access by granting licenses to private universities and setting up new ones of her own.

In 2011 alone, the government set up nine new federal universities. It is axiomatic that wherever enrolment expands too quickly, the first casualty is quality. Expanding access without paying corresponding attention to factors that actually determine quality of teaching and learning will ultimately devalue education. It is no surprise therefore that one of ASUU’s demands is that government should stop the proliferation of universities. Related to the issue of quality is also the issue of relevance both in terms of curriculum content and in terms of course preferred by students relative to the needs of the employment market and the nation’s manpower needs.

The Association of African Universities has identified weakness in curricula and how they are delivered as major factors in explaining the declining quality of graduates in Africa: “The orientation of curricula needs to shift away from producing theoretical elites and administrators to produce doers and entrepreneurs who are transformational wherever they find themselves.

Due to poor remuneration and poor facilities, African HEIs are not competitive in attracting and retaining top instructors.”17 In addition to this is the question of what the students are applying to study and how these courses will help their prospect of getting a job or contributing in areas that the country needs their expertise. In 2019, while 1,874 graduated in Medicine and 923 in Computer Engineering, 10,261 graduated in Accounting, and 6,239 in Political Science in the same year.

Other reports also show that Education and Agriculture are the only two courses for which universities are not receiving enough applications, yet these are areas of critical manpower needs for the country.18 The issue of curriculum is also related to that of governance. Over-centralisation of the university system has created a sense of uniformity that has robbed every university the chance to develop a unique character of its own. Almost every university offers the same menu of courses without regards to the needs of its local environment or its own capabilities.

As stated earlier, higher education system in Nigeria must be situated within a national human resource development strategy, which in turn must derive from a broader national development plan. Therefore, transforming the public universities in Nigeria will not be a job for the minister or the Ministry of Education alone. The Ministry of National Planning, the Ministry of Labour and Productivity and the Organised Private Sector (OPS) must work closely together. But the process has to be led by the President of the country or someone who has his convening authority to drive the process.

The 2023 webometrics ranking of African universities includes less than 10 Nigerian universities in the top 100. While these rankings may be taken as fair indicators of our universities’ standing within the parameters being measured either in a global or regional context, they are not sufficient in measuring our higher education institutions’ responsiveness to the national development needs. We need a new system of evaluation and quality assurance that is semi-autonomous and has a strong private sector orientation.

It is important for the private sector to play a leading role in quality assurance because they are the major off takers of what the universities produce as students or as research. Acting Director of the Innovation and Technology Management Office of the University of Lagos, Abiodun Gbenga-Ilorin, recently stated that 13,282 research papers were published in Nigeria in 2020, which ranks the country 50th in the world in the number of research papers published that year. However, of all these, only 300, about 2.2 percent has led to successful innovations. Working closely with the industries will ensure that research focus becomes more demand- and solution-driven, plus the added benefit of attracting good funding19.

Summary of Recommendations

- Federal Government needs to step back. Less government is best for universities. Government should grant full autonomy to its public universities, and allow each university to develop its own identity and grow at its own pace.

- National Universities Commission Act (1974) should be amended to release its stranglehold of NUC on the universities and assign it a coordinating and monitoring role rather than a directive or prescriptive role.

- In keeping with the principle of autonomy, government should cede its role as employers of university lecturers to each university. This will empower the universities to negotiate terms and conditions of service with their respective employees in line with their local reality and the value expected of each lecturer.

- A realistic annual cost for each student should be determined and the universities should be funded by government based on the number of students rather than personnel or administrative needs of the university.

- Universities should be allowed to charge tuition fees within the parameters set by government, but the Education Bank needs to be established to offer federal government-backed loans to students who may require them.

- Government and institutional scholarship awards are another opportunity for talented but indigent students to pay tuition. Most government scholarships now are targeted at students studying abroad. This should be reversed.

- Work-study also presents another option for indigent students. Most of the work currently being done by non-academic staff and even contract staff in the universities can be done by students.

- Endowment funds are a major way for universities to expand their pool of funds. Currently, the universities are not tapping into it as much as they should do. They need to bring their alumni closer and give them incentives to contribute to their university endowment programmes and to establish scholarship schemes and give back in other ways.

- A new framework for tertiary education funding needs to be developed that will set objective parameters for allocation of funds from the TETFUND based on verified outputs in teaching, research and community service.

- A semi-autonomous National Higher Education Quality Assurance Agency (NHEQAA) needs to be established to monitor the quality of teaching and research in the universities, and evaluate them in terms of their responsiveness to the nation’s manpower requirement and economic development plan.

*Abudullahi, an education enthusiast, was Commissioner for Education in Kwara State and Minister for Youth Development and Sports.

Footnotes

[1]IBRD/WB. (2003), Directions in Development - Lifelong Learning in the Global Knowledge Economy: Challenges for Developing Countries, World Bank, Washington DC; and Kosack S. (2020). The Education of Nations: How Political Organisation of the Poor, Not Democracy, Led Governments to Invest in Mass Education; Oxford University Press, New York.

[2] In projecting for 15 years, I adopt the cycle for the United Nations Millenium/Sustainable Development Goals.

[3] National Universities Commission Act, 1974.

[4] Pritchett L., (2013). The Rebirth of Education; Centre for Global Development, Washington DC.

[5]https://businessday.ng/news/article/explainer-asuus-demands-and-what-government-has-met/

[6]This is according to a 2013 paper delivered by Prof. Rahmon Bello, former Vice-Chancellor, University of Lagos.

[7] Some reported going months without receiving any overhead allocation.

[8] These are sundry fees charged at the discretion of each university. Tuition remains free of charge.

[9]The table captures the minimum payable. Fees normally varies, with significant upper bound in the same university, depending on the courses.

[10]The N2,220,000 is arrived at by charging N74,000 per credit for a 30-credit academic session.

[11] Kosack S.(2012), Ibid.

[12] https://guardian.ng/features/stakeholders-canvass-implementation-of-education-bank-act/

[13] https://dailytrust.com/asuu-opposes-students-loan-bill/

[14] See Punch Newspaper, April 18,2022. [15]https://tetfund.gov.ng/index.php/mandate-objectives/

[16] Kosack S. (2012). Ibid. Pg 25.

[17] Strategic Plan 2020-2025 (Accra, 2020). Pg. 18.

[18]https://punchng.com/367499-applied-for-43717-medicine-slots-jamb-report/

[19] TETFUND allocation to each university for research in 2023 is only N40 million or $86,000.

Read more: Repositioning Nigeria’s Public Universities for National Growth and Competitiveness

- Details

- By Agora Policy

- Policy Memo

- Hits: 1320

By Babajide Fowowe | Nigeria is currently struggling with a severe crunch in the supply of foreign exchange (forex), which negatively impacts the value of the Naira, its national currency. Both the official and the unofficial forex markets are afflicted by what is basically a liquidity and flow challenge. A number of initiatives and ideas have been mooted which largely relate to borrowing or finding ways to incentivise portfolio flows. Despite supportive oil prices, there is limited discussion around boosting organic forex flows from Nigeria’s oil exports.

Beyond improving security in the Niger Delta to curtail oil theft and re-engaging with capable partners to raise investments in oil production in the country, a short-term and sustainable fix for oil revenue and ultimately for increased forex flows will be for the Nigerian government to immediately cancel the policy of earmarking for domestic consumption a portion (and increasingly all) of its own share of oil output.

Of all the options being implemented or considered for boosting forex inflow into Nigeria, cancelling what is termed Domestic Crude Allocation (DCA) is Nigeria’s surest bet. This will yield immediate result and provide a steady (not one-off) flow of foreign exchange—and thereby address the cashflow challenge in the official segment of the forex markets. Additionally, it will end the dodgy deductions and accounting associated with the domestic crude allocation policy that has been aptly described as an active crime scene.

The DCA has acquired an outsized profile of recent. Any serious attempt at understanding and reforming how Nigeria’s share of oil is accounted and paid for must, for a number of reasons, zero in on the management of and the recent prominence of the DCA.

With the drastic reduction in oil production in Nigeria and the shift in production arrangements away from Joint Ventures (JVs) to Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs), most of the Federation’s share of crude oil produced in Nigeria is channelled to DCA, which has dramatically risen from below 10% of Federation’s share of oil in the early 2000s to almost 100% by 2023. This is not just a suboptimal allocation issue. In relation to forex flows, it is a key challenge because the revenue from DCA sales is received in Naira, meaning that the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) is starved of steady and healthy flow of foreign exchange from what used to be its dominant source: crude oil sales. As at 2010, flows from oil and gas accounted for 94% of forex to the CBN but plummeted to 24% by June 2022, and is conceivably much lower now (CBN, like NNPCL, has stopped disclosing some critical data).

Crude oil exports still account for over 70% of Nigeria’s total exports but since 2016 an increasingly disproportionate percentage of the country’s share of crude oil exports is earmarked for domestic consumption. The earmarked barrels of crude oil return first as petrol, then, in terms of monetary flow, as Naira, not dollars. This is because the resultant petrol from DCA is paid for in Naira, not dollars. It is worth highlighting that there is no guarantee that the Naira payment from DCA would translate to commensurate, or even any, revenue to the Federation Account. This is because the national oil company has always been in the habit of making upfront deductions for sundry reasons from revenue accruing from the DCA. The DCA is the site where NNPC performs its dark magic.

Crucially, the DCA policy not only provides an insight into why the national oil company failed to make remittances to the Federation Account for a long spell but also explains why forex inflows from sales of Federation’s crude oil dwindled and the country’s external reserves stagnated at a period of historically high oil prices.

Countries with low forex supply against demand can adopt a number of measures to increase foreign exchange inflows. Such measures include external loans, deposits by deep-pocket investors and countries, foreign direct investment (FDI) and foreign portfolio investment (FPI) and increasing other sources of exports (non-oil exports in Nigeria’s case). However, loans are likely to be one-off and have to be repaid and with interests (even if concessional). Investors are known to take their time and they can be fickle. Unlocking other sources of exports requires time too.

While the country needs to pursue all these options as both stop-gap and long-term measures, it should urgently embrace the one option that is largely under its control and can ensure a steady and sustainable flow of foreign exchange: earning dollars from the sale of its crude oil wherever it is sold. For this to be possible, the DCA policy needs to go immediately. Cancelling the DCA is the easiest and most predictable way to boost forex flows into Nigeria and the most realistic way to reduce pressure on and provide relief for the Naira.

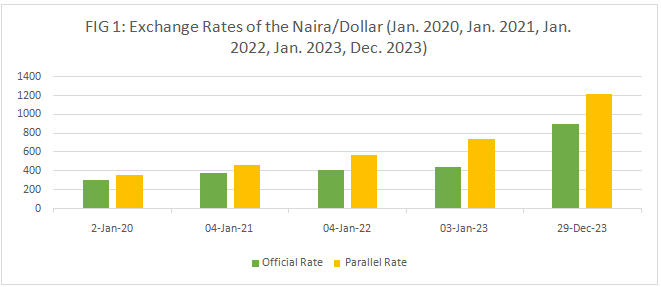

DCA as the Missing Part of the Forex Puzzle

On23 September 2023, the exchange rate of the Naira to the U.S. dollar on the parallel market reached N1,004/$1, thus crossing the N1000/$ psychological mark1. This marked a significant milestone in the foreign exchange markets in Nigeria. The exchange rate of the Naira has been under pressure for some years, andit has been particularly unstable in the past three years. On 2 January 2020, the Naira exchanged for the dollar at N306.5/$ and N360.5/$at the official and parallel markets respectively (Figure 1).On 29 December 2023, the exchange rates of the Naira to the dollar jumped toN899.9/$ (official) and N1,215/$ (parallel) (Figure 1). Compared to the 2 January 2020 rates, this represents a depreciation of 66% for the official rate and 70% for the parallel rate.

Sources: Central Bank of Nigeria; Analysts Data Services and Resources

While many analysts and commentators have provided different explanations (including conspiracy theories) about factors responsible for the depreciation of the Naira, the primary cause is the simple economics law of demand and supply: the supply of foreign exchange in the country has not been sufficient to meet the demand. The country has a backlog of foreign exchange obligations estimated at between $4 billion and $7 billion by the new Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN)during his Senate confirmation screening2,3. The backlog has been occasioned because there was simply not enough foreign currency in the country to meet demand. While the restrictive policies of the CBN had been able to suppress the effects of the pent-up demand on the exchange rate, the recent liberalisation has shown the full extent of the excess demand.

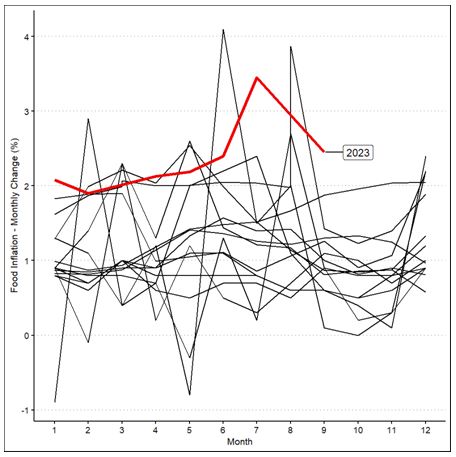

Following the removal of foreign exchange controls on 14 June 20234, the Naira was effectively floated, and the workings of market forces saw an immediate depreciation of 29% at the Investors and Exporters (I & E) window, with the exchange rate moving from N471.67/$1 to N664.04/$1. Further liberalisation came on 12 October 2023 with the removal of foreign exchange restrictions on imports of 43 items5.While the removal of these foreign currency restrictions has on one hand limited subsidisation in the foreign exchange markets, on the other hand, it has resulted in increased prices for imported goods (including petrol), and higher costs for foreign transactions (such as school fees and medical costs). This, coupled with seemingly constantly rising prices, has meant that the exchange rate of the Naira has been a dominant topic of discussion in the polity for the past six months.

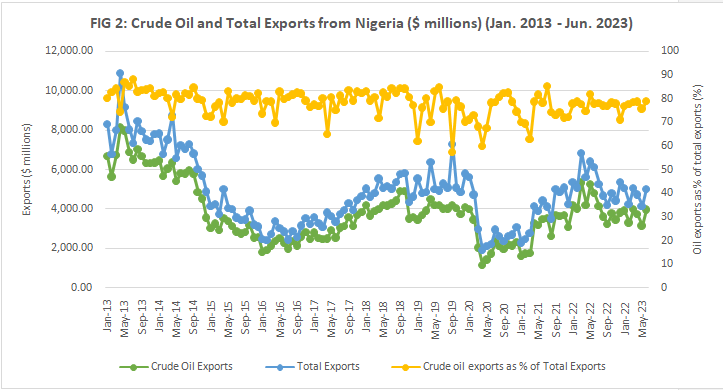

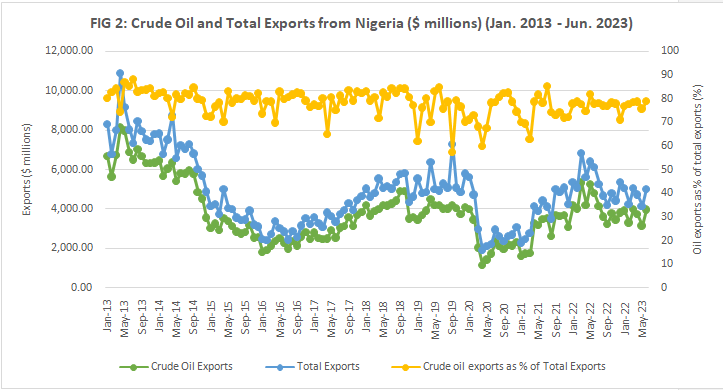

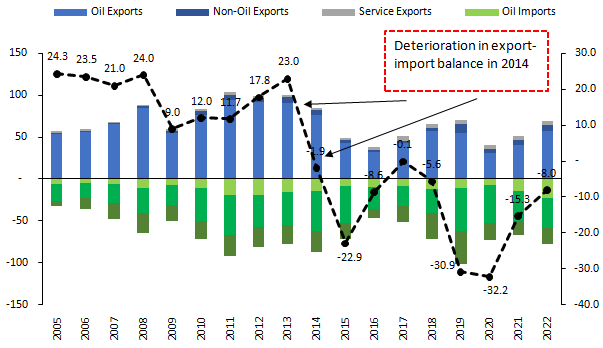

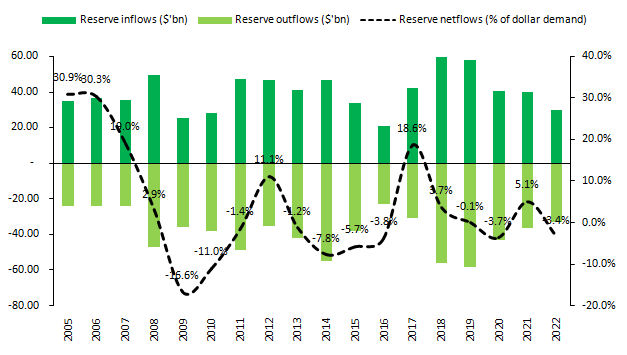

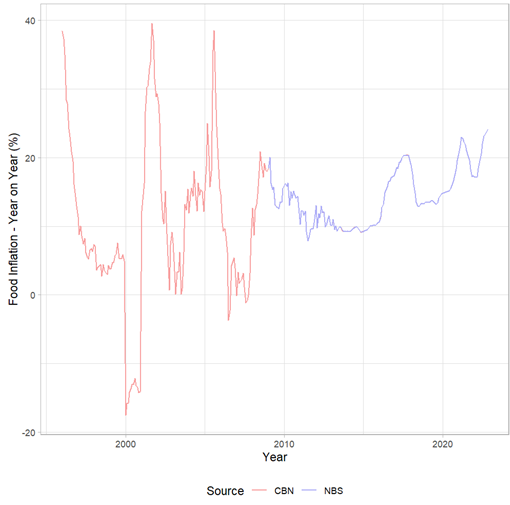

Despite the reforms, a lingering issue for Nigeria and the value of the Naira is that the supply of forex continues to track below demand. At the heart of the reduced supply of foreign exchange is the decline in USD inflows into Nigeria’s external reserves arising from lower oil receipts. A key explanation for this is the drastic reduction in oil production, and consequently oil exports. Oil exports have typically accounted for over 70% of total exports (Figure 2), and have, since the commencement of commercial oil exploration, provided the bulk of foreign exchange earnings for the country. However, oil production started falling drastically in the second half of 2020, and remained largely below 1.4 million barrels per day (Figure 3). Production dropped further in 2022 and was below one million barrels per day in August and September. Although it subsequently increased, production has not risen above 1.4 million barrels per day since then. The country has not been able to meet up with OPEC production allocations since July 2020 (Figure 3). Between March 2022 and August 2023, the shortfalls were so acute that they were above 450,000 barrels per day.

Source: Central Bank of Nigeria Quarterly Statistical Bulletin, 2023 Q2

Notes: 1. Crude oil exports as % of Total Exports are measured in percentages on the right-hand vertical axis

2. Crude oil exports and Total Exports are measured in millions of dollars on left-hand vertical axis

Sources: Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission and OPEC Statistical Bulletin

Though a lot of attention has rightly focused on declining oil production with government officials and the media putting the blame on oil theft, this is only a part of the story as oil prices after declining over the 2014-16 period and during the COVID-19 pandemic have been broadly supportive of oil export receipts. Ordinarily, the decline in oil production should have been compensated for by significant rise in oil prices following the war in Ukraine. However, there has been a secular decline in the ratio of oil inflows into Nigeria’s external reserves and oil export receipts. We posit in this paper that the reduced forex flows reflect increased allocation of Federation’s crude to DCA at the expense of direct Federation oil exports which normally translated to dollar flows.

DCA involves ‘domestic’6 sales of crude oil, thereby bringing revenues in Naira, the domestic currency. Depending on the terms of the different production arrangements, crude oil produced in Nigeria is shared between the oil companies and the Federation. NNPC is responsible for selling the Federation’s share of the total oil produced. NNPC in turn allocates the Federation share either for exports or for domestic utilisation7. It is the component for domestic utilisation that is referred to as domestic crude allocation (DCA). The critical point to note is that the different allocations are paid for in different currencies: revenue from Federation exports is received in dollars and revenue from DCA is received in Naira.

With the dwindling oil production, a larger proportion of the Federation’s quota has increasingly been channelled to DCA. This has led to the situation where most of the oil revenue inflows have been in Naira, as opposed to dollars. It is our considered position that switching crude oil allocations from the DCA to exports will provide steady revenue in foreign exchange, and thus boost foreign exchange supply in Nigeria. Ultimately, an increased and steady supply of foreign exchange will ease demand pressures and help to stabilise the Naira.

Good Intention Gone Sour

The current outsized role of the DCA started around 2005 with the arrangement that about 445,000 barrels of crude oil per day (the nameplate capacity of the Nigeria’s four government-owned refineries) be set aside from Federation’s share of oil, and be channelled for domestic refining through sales to the then Pipelines and Product Marketing Company Ltd. (PPMC).The allocation would be paid for in Naira and PPMC would recoup proceeds via distribution and sale of the resulting refined products within Nigeria. The rationale was that such exclusive domestic allocation of crude oil would guarantee energy security, de-link refined petroleum product prices from volatility in exchange rates and international crude oil prices, and ensure adequate supplies of refined petroleum products in the country.

On the surface, the DCA seemed to be a reasonable idea, and a number of benefits of such an arrangement can be easily gleaned. It would help to insulate the country from price volatilities in the global oil markets. Such volatilities would be manifested in higher or unstable prices of petroleum products, scarcity of petroleum products, and uncertainty or unstable supply of petroleum products. Effectively, domestic crude allocation would ensure that Nigerians reap considerable benefits from being citizens of a major oil-producing

country. However, the policy had one notable weakness: a flawed pricing framework. On the one hand, the crude from the DCA was sold to the PPMC at an implied discount in dollar terms, when adjusted for the exchange rate, in comparison to the international market. On the other hand, the Naira sales price for refined products was delinked from Naira cost price to PPMC implying a subsidy whose bill was to be covered in annual budgetary allocations. In essence, the DCA created two layers of potential losses: first to the Federation in terms of potential export revenues and second to external reserves in the form of forex inflows. In addition, in de-linking domestic petrol prices from the underlying cost drives of refined petroleum products, the DCA pretty much created an incentive for the expansion of Nigeria’s petrol subsidy programme. The failure to incorporate the opportunity cost concept in economics would have dire implications further down the line for fiscal revenues and dollar proceeds while creating perverse incentives for malfeasance.

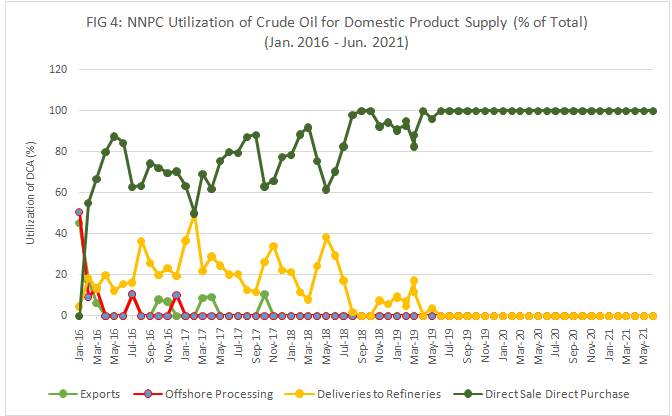

In what follows, we highlight some of the critical problems of the DCA8.Firstly, the losses borne by the PPMC provided little legroom to make the required investments in Nigeria’s domestic refineries which gradually fell into disrepair. Nigeria’s domestic refining capacity fell to low digits with zero allocation to the refineries from the DCA in 2020. While the loss in domestic refining capacity should have resulted in a termination of the DCA policy, successive Nigerian governments, desirous of ensuring low domestic fuel prices, responded by using the DCA barrels to enter into different arrangements (such as swap, offshore processing arrangements and direct sale and direct purchase) with international refineries and commodity traders to basically barter crude for refined petroleum products.

For much of the earlier period, the actual DCA arrangements amounted to sacrificing an insignificant share of Nigeria’s oil production for refined petroleum products. Given relatively tepid international oil prices for the much of the 1990s and early 2000s, the arrangement was not burdensome from a fiscal and FX perspective. Importantly, DCA usage was below 10% of the total Federation share of oil. However, by 2005, the decision to allocate about 445,000 barrels per day to DCA bumped up significantly the share of the Federation oil allocated for domestic consumption.

In 2004, for instance, only 39 million barrels or 8.57% of the 455 million barrels of the Federation share was allocated to domestic consumption, with the remaining 91.43% allocated to Federation exports. Following the policy mentioned earlier, the picture changed dramatically in 2005, with 160.9 million barrels or 35.25% of Federation’s share of 456 million barrels set aside for domestic consumption. The percentage devoted to DCA has steadily increased since then. In the early stages, NNPC refined some of the allocation locally, swapped some for refined products abroad, and exported the rest, which it paid for in dollars. Before long, things went downhill. The refineries basically collapsed, the crude for domestic consumption was all refined abroad or bartered, upfront deductions by NNPC from DCA increased, and the petrol subsidy programme soared.

Since 2016, DCA crude has been increasingly sold through the Direct-Sale Direct-Purchase (DSDP) arrangement (Figure 4). While the refineries no longer receive crude oil, the DSDP arrangement ensures that crude oil receipts are still in Naira, as opposed to dollars.

Sources: NNPC Monthly Financial and Operations Reports

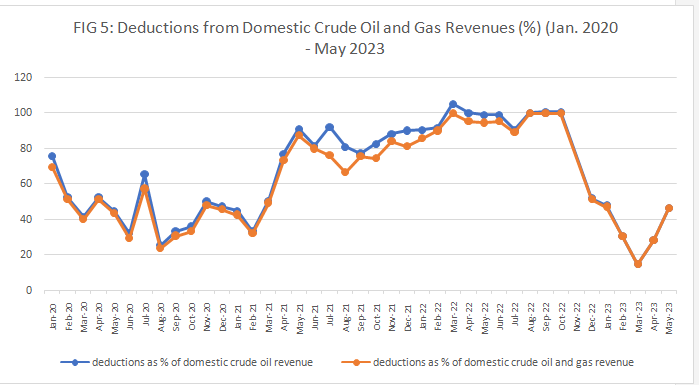

Second, the larger proportion of revenuefrom DCA was largely retained by the NNPC, meaning that the Federation progressively received less and less. Revenue from the DCA has been used by the NNPC for many years to finance its operations. Payments for subsidies, pipeline repairs and maintenance, product losses and lately JV cost recoveryare financed with DCA receipts. In January 2020, total deductions as a percentage of domestic crude oil revenue were 75% (Figure 5). This fell and reached 24% in August 2020. However, it started rising and reached 100% in March 2022. With the exception of July 2022 when it fell to 89%, it remained at 100% until October 2022.

This implies that all revenues from DCA were retained until October 2022, which also coincided with when NNPCL stopped making remittances to the Federation Account. The implementation of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA) resulted in changes to the composition of deductions, leading to its percentage as a share of domestic crude oil and gas revenue falling to 15% in March 2023, before rising to 46% in May 2023 (see Box 1 for a more detailed description of deductions). Reporting of deductions ended in June 2023. The implementation of the PIA, coupled with removal of petrol subsidies, likely reduced the burden of deductions.

Sources: NNPC Presentations to the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) Meeting

Notes: 1. Between January 2020 and October 2022, total deductions consisted of JV Cost Recovery + Total Pipeline Repairs and Management Cost + Total Under-Recovery + Crude Oil & Products Losses + Value shortfall

2.The author was unable to obtain data for November 2022

3. Between December 2022 and May 2023, official deductions consisted of JV Cost Recovery + PSC(FEF) + PSC (Mgt Fee).

4, From June 2023, NNPC stopped reporting deductions as previously constituted.

5. See Box 1

| Box 1: Composition of Total deductions from DCA (January 2020 to November 2023 |

|---|

|

1) Between January 2020 and July 2022, total deductions consisted of three components: a. JV Cost Recovery (T1/T2)

b. Total Pipeline Repairs and Management Cost

i. strategic holding cost ii. pipeline management cost [January to April 2020, June 2020] iii. pipeline operations, repairs and management cost c. Total Under-Recovery + Crude Oil & Products Losses + Value shortfall

i. crude oil & product losses [reversal of product loss in May 2022 ii. PMS Under-recovery (Current + arrears) [January 2020 to April 2020] iii. Value loss due to deregulation [July 2020] iv. NNPC value shortfall (recovery on the importation of PMS/ arising from the difference between the landing cost and ex-coastal price of PMS) [March 2021 to October 2022] 2. For some months, the only deductions were for JV cost recovery [October 2020, January 2021, February 2021] 3. For August 2022, the only deductions were for NNPC value shortfall 4. From September 2022, there were changes in NNPC’s deductions, attributed to the PIA: a. Dollar deductions for NNPC value shortfall: 40% of PSC profit due to Federation (in addition to naira deductions: 100% of DCA revenue); b. No deductions for JV cost recovery and total pipeline repairs and management cost. Deductions for JV cost recovery resumed in December 2022; 5. From December 2022 (unclear if this change happened in November or December, as we were unable to obtain data for November), the composition of deductions changed and consisted of: a. JV cost recovery (naira and dollars) b. PSC Frontier Exploration Funds (FEF) (dollars, naira deductions started in February 2023) c. PSC (Management Fee) (dollars, naira deductions started in February 2023) 6 From December 2022, statutory payments to NUPRC (royalty) and FIRS (taxes) which had stopped in July 2021, commenced again (payments were made in September 2022) 7. From December 2022, payments started for NUIMS for profits 8. From February 2023, Payments for Federation PSC Profit Share in naira started (in addition to payments in dollars which started in December 2022) [40% of gross oil and gas revenue] 9. From December 2022 to May 2023, the addition of the official deductions (JV + PSC(FEF) + PSC (Mgt Fee), statutory payments (NUPRC + FIRS), NUIMS profits, and PSC profit share (from Feb 2023) are equal to DCA revenue. 10. From June 2023, NNPC stopped reporting deductions on the template. Rather, there was a section called Transfers, comprising 2 components: a. Transfer from PSC profits, comprising: i. PSC (FEF) ii. PSC (Mgt Fee) iii. Federation PSC profit share b. NNPC Ltd. calendarized Interim dividend to Federation Account c. The addition of the components under Transfer from PSC Profits was equal to total revenue from domestic crude oil and gas sales |

In recent years, Nigeria’s oil production (including condensates) has declined from the standard 2m barrels per day (mbpd) to a low of 1.1mbpd though this has recently stabilised around 1.4-1.6mbpd. As a result,crude oil production has not been able to meet budgetary targets or OPEC production allocation quotas as shown in charts above. This failure has been attributed to reflect a mixture of theft, outages from downtime during repairs and declines in underlying production as Nigerian oil fields mature in the face of reduced investments.

Since the 2010s, international oil majors have scaled back investment in Nigeria in the face of regulatory uncertainty following the delayed passage of the Petroleum Industry Bill, rising operating costs due to increased security and environmental clean-up, and growing pressures from climate change activists to cut emissions from oil projects with high greenhouse gas emissions. These factors have pushed oil majors to shift investments away from the high-cost onshore fields with less attractive fiscal terms to deep offshore projects with more favourable fiscal terms and greater stability. The preference for offshore assets has seen a wave of asset disposals of onshore fields to domestic producers who have struggled to increase production given their weaker access to global capital markets to raise financing for exploration and production.

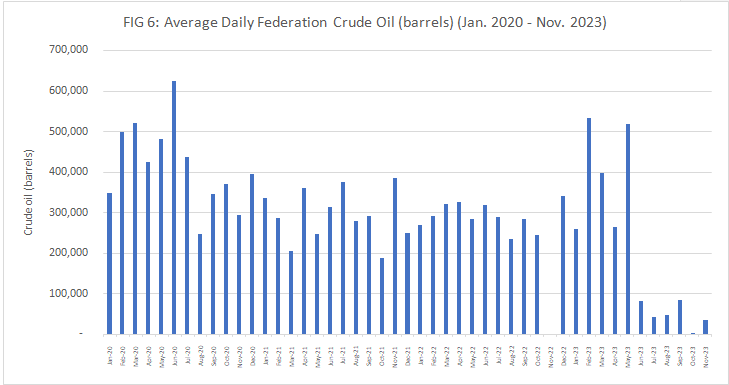

The derivative of the reduced oil production is that the Federation’s share of oil production has fallen dramatically. The daily average of the Federation’s share of crude oil was 414,463 barrels in 2020, 292,198 barrels in 2021, 290,649 barrels in 2022, and 205,184 barrels in 2023 (Figure 6). These are far below the daily average of one million barrels per day that accrued to the Federation between 2004 and 20149.Another important dynamic of import is that Nigeria’s oil production is now largely concentrated in Production Sharing Contracts (PSCs), where, by their design, oil companies get a larger share of production.

Sources: NNPC Presentations to the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) Meeting

Notes: 1. The author was unable to obtain data for November 2022

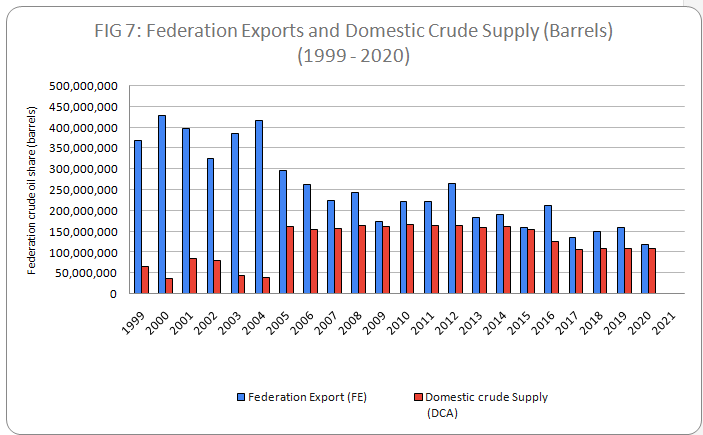

The net effect of the lower Federation share of crude oil is that domestic crude has assumed a larger portion of the Federation’s share of crude oil (Figure 7). As total Federation crude has fallen continuously in the past four years, an increasingly larger share has been allocated for domestic sales (Figure 8). Domestic crude allocation reached 99% of total Federation allocation in May 2021. Since then, it has not fallen below 95% (exceptions were in June 2021, March 2022, February - March 2023, June – August 2023, October 2023).

The dominance of domestic crude allocation has important implications for the foreign exchange market. Because sales of domestic crude are received in Naira, the fact that virtually all Federation sales of crude oil since May 2021 have been of domestic crude means that the bulk of crude oil revenue has been received (when it is received) in Naira, rather than in dollars. The fact that crude oil revenue is no longer being received in dollars has important negative implications for the supply of dollars in the economy, and the nation’s external reserves.

Sources: NEITI Oil and Gas Audit Reports

Sources: NNPC Presentations to the Federation Account Allocation Committee (FAAC) Meeting

Notes: 1. The author was unable to obtain data for November 2022

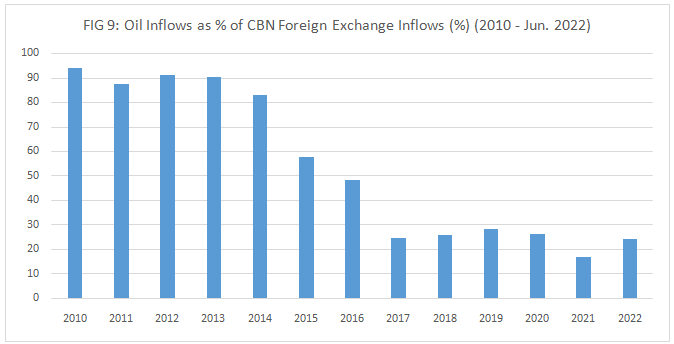

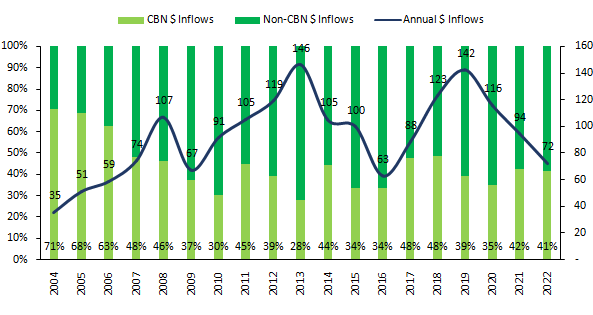

The oil and gas sector has traditionally accounted for the largest part of foreign exchange inflows to the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) (Figure 9). In 2010, foreign exchange inflows through the oil sector accounted for 94% of total inflows through the CBN. However, this started falling and had dropped to 24% in June 2022 (January to June).Foreign exchange inflows through the oil sector which were above 80% between 2010 and 2014, fell and remained below30% from 2017 to 2022 (Figure 9).

Source: CBN Quarterly Statistical Bulletin, volume 11, no. 2, June 2022

Notes: 1. The data ends in June 2022, because the CBN no longer provides disaggregated data on foreign exchange inflows

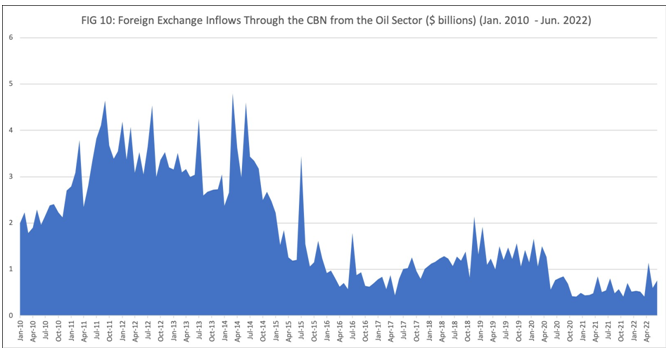

In January 2010, the oil sector brought in $1.99 billion through the CBN. This increased and reached $4.79 billion in March 2014 (Figure 10). Following this, it started falling and dropped to $922 million in January 2016. It rose and remained largely above $1 billion between July 2017 and April 2020. Then, it started falling and remained below $1 billion until June 2022 (with the exception of April 2022). Optically, the secular downtrend in oil inflows coincided with the start of the DSDP programme which used DCA crude allocation at a period of low oil prices. Following the recovery in prices over 2017 and in the 2021-2022 period, oil inflows have failed to recover mainly because most of Federation’s share of oil is being allocated for domestic consumption which does not translate to forex earnings. At an average price of $100/bbl and $84/bbl over 2022 and 2023, the nameplate DCA crude of 445kbpd would have translated into monthly inflows of $1billion to external reserves. However, as these sums were likely received in Naira, the opportunity cost is the reduced supply of FX by the CBN and the resulting demand pressures on the Naira.

Source: CBN Quarterly Statistical Bulletin, volume 11, no. 2, June 2022

Notes: 1. The data ends in June 2022, because the CBN no longer provides disaggregated data on foreign exchange inflows

While quick fixes cannot be implemented for returning steady foreign exchange inflows from oil to the levels experienced 10 years ago, ending the DCA and exporting the Federation’s share of crude oil can provide a steady supply of foreign exchange inflows. This would boost oil sector foreign exchange inflows through the CBN above the average of 24.2% experienced between 2017 and 2022. Assuming an average oil price of $70/bbl, the cessation of DCA could, before deductions, net $900million monthly which should bolster USD liquidity flows within the FX market. Critically, this will not be a temporary measure, but will be a steady supply of foreign exchange as long as crude oil is sold. Such steady supply will help in bringing some stability to the foreign exchange markets.

Fundamentally, with the removal of petrol subsidiesand the implementation of the PIA, there are virtually no more reasons for continuing with the DCA. Furthermore, the onset of the Dangote Refinery with a nameplate capacity of 650kbpd alongside recent announcements regarding a mechanical completion of repair work at the Port Harcourt Refinery (150-210kbpd) would imply a DCA that will further dim the prospects of forex from Federation’s share of oil if receipts are in Naira. Beyond legal realities, the DCA is impractical given the evolving dramatic changes in domestic refining capacity.

A caveat about the removal of petrol subsidies and implementation of the PIA is needed.

First, on subsidies, there have been reports that petrol subsidies are back in some form. The Petroleum and Natural Gas Senior Staff Association of Nigeria (PENGASSAN) has stated that the government has restored subsidies10. The World Bank indicated the reemergence of an implicit petrol subsidy11.The Independent Petroleum Marketers Association of Nigeria (IPMAN) has also said subsidies have only been reduced, but not removed12. Careful consideration and strategic planning are needed on the issue of subsidies. The oft-touted palliative measures to alleviate the increase in cost of living of the hike in petrol prices have yet to fully materialise. This, perhaps, has been responsible for the reluctance of the government to allow the prices of petrol to fully reflect market prices. There needs to be a well-thought out and clear policy direction on the issue of petrol subsidies and the need to pursue full deregulation and extricate the country from the awkward and perverse incentives-ridden situation where NNPCL becomes the sole importer of petrol.

Second, on the PIA, recent guidelines by the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) have addressed the argument that local refineries need to be supplied with crude oil13. However, it is hoped that the new guidelines will stipulate that such domestic sales of Federation crude, if applicable, will be quoted in international prices and the payment will be made and received in foreign exchange. Failure to do this and properly manage and administer these new guidelines could present DCA version 2.0. Also, strict payment schedules must be stipulated and adhered to, so that there will be no backlog of payments. If properly administered, this new policy should not adversely affect foreign exchange inflows.

Conclusion

We have conducted an analysis of the rapid depreciation of the Naira in recent years. The central theme is that the supply of foreign exchange has not been able to meet up with its demand, leading to a backlog of foreign exchange obligations estimated at between $4 billion and $7 billion. With oil exports acting as a major enabler of foreign exchange inflows, the nation’s dwindling oil production was identified as an important contributor to lower supply of foreign exchange.

With lower oil production, higher proportions of the Federation’s share of crude oil have been allocated to domestic crude sales. Revenue from domestic sales is received in Naira, as opposed to dollars, thereby heightening scarcity of foreign exchange. We submit that the DCA has outlived its usefulness, and its continued use has proved costly to the country, especially for inflows of foreign exchange, thereby hurting the Naira. We recommend ending the DCA and selling Federation’s crude oil for exports, or if sold domestically to private refineries, to be sold in dollars. If this is done, steady inflows of foreign exchange will boost supply of foreign exchange, provide some quick wins to address foreign exchange scarcity, and help to maintain some level of stability for the Naira.

In October, the Federal Government announced plans for the injection of $10 billion of foreign exchange inflows14. These are expected to materialise from a variety of sources. Two executive orders were signed by the president in October: the first one will enable dollar-denominated instruments to be issued for purchase within the country; while the second is for issuance of dollar-denominated bonds for purchase by investors outside Nigeria15. Also, foreign exchange inflows are expected to receive a boost from the NNPCL through increased production, transactions such as forward sales, and investments from sovereign wealth funds16. In addition, NNPCL in August announced a $3 billion emergency crude oil repayment loan from the African Export Import Bank (Afrexim bank) “to support the Naira and stabilise the foreign exchange market”17.

Our central argument in this intervention is that while these measures can offer some succour and ease the pressure on the Naira, they do little to ensure a steady inflow of foreign exchange. They only provide emergency and temporary relief for foreign exchange stability.

In some instances, these measures have costs that, when fully considered, seem to outweigh the benefits. For example, the arrangement between NNPCL and Afrexim bank is a ‘pre-export finance facility’ (PxF) where the country has pledged 90,000 barrels per day for five years (2024 – 2028)18. This facility attracts an interest rate of 11.85%, which does not compare favourably with lower interest rates charged by international institutions for a longer period19. It is difficult to contextualise how the net effect of this facility will be of benefit, rather than loss to the country. It is more productive for NNPCL to concentrate on its core mandate and for the government to focus on how Nigeria can start earning foreign exchange again from the sale of the Federation’s share of oil. The DCA needs to go immediately.

*Professor Fowowe is an energy economist.

** Wale Thompson and Ifetayo Idowu contributed to this paper.

Footnotes

[1]The rate rose to N1,099.05/$1 on 8 December 2023 at the I & E window, but dropped back below N1,000/$1

[2] https://punchng.com/cardoso-to-clear-dollar-debts-suspend-intervention-loans/

[3] https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/nigerias-central-bank-governor-cardoso-pledges-clear-7-billion-forex-backlog-2023-09-26/

[4] https://www.cbn.gov.ng/Out/2023/CCD/CBN%20Press%20Release%20%20FX%20Market%20121023.pdf

[5]In reality, for many years, the crude oil has neither been utilized nor sold domestically, hence, the term ‘domestic’ has become a contradiction.

[6]NEITI 2021 Oil and Gas Audit Report

[7] Sayne, A., Gillies, A. and Katsouris, C. (2015) Inside NNPC Oil Sales: A Case for Reform in Nigeria, Natural Resource Governance Institute.

[8]https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/631482-nigerian-govt-still-pays-subsidy-on-petrol-pengassan.html

[9]https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/099121223114542074/pdf/P5029890fb199e0180a1730ee81c4687c3d.pdf

[10]https://punchng.com/nnpcl-marketers-clash-over-subsidy-operators-peg-petrol-at-n1200-litre/

[11]https://www.nuprc.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/DOMESTIC-CRUDE-SUPPLY-OBLIGATIONS.pdf

[12]https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/636428-nigeria-expects-10-billion-forex-inflows-in-weeks-minister.html

[13]https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/nigeria-plans-new-fx-rules-in-hopes-of-naira-reaching-fair-price-by-end-of-2023-1.1991306#:~:text=Nigeria%20expects%20to%20receive%20%2410,summit%20in%20Abuja%20last%20week.

[14https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/636428-nigeria-expects-10-billion-forex-inflows-in-weeks-minister.html

[15]https://www.thecable.ng/report-afreximbank-approaches-oil-traders-to-finance-3bn-loan-to-nnpc

[16]https://www.thecable.ng/exclusive-nigeria-to-pay-11-85-interest-on-3-3bn-afriexim-nnpc-loan-pledges-164m-barrels-as-security#google_vignette

[17]Ibid.

- Details

- By Agora Policy

- Policy Memo

- Hits: 1075

By Wale Thompson | In a surprise move on 14 June 2023, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) announced the removal of all restrictions on foreign exchange rates and signalled a willingness to tolerate greater flexibility in exchange rate determination as against the previous practice of a hard peg. In simple terms, the CBN ‘floated’ the Naira. This announcement was accompanied by directives which unified the multiple FX tiers invented by Mr. Godwin Emefiele, the suspended CBN governor, and specified the re-introduction of a “willing buyer, willing seller” arrangement for Nigerian foreign exchange markets.

This policy shift was consistent with the expressed desire of President Bola Tinubu for a unified exchange rate in his inauguration address of 29th May 2023, as well as the yearnings of private businesses, analysts and financial market investors, who had been frustrated at the arcane rules and lack of liquidity associated with the previous era. In its aftermath, the Naira has lost around 40% of its value within the official window to close at NGN770/$ on the first day of trading, a development that has elicited a mix of cautious optimism and pessimism. While praises have poured in from international financial organisations, business elites and financial market investors and western countries, the fledging reform has also attracted an avalanche of knocks from segments of the media, labour unions and a growing number of citizens struggling with continued depreciation of the Naira and its adverse inflationary effects.

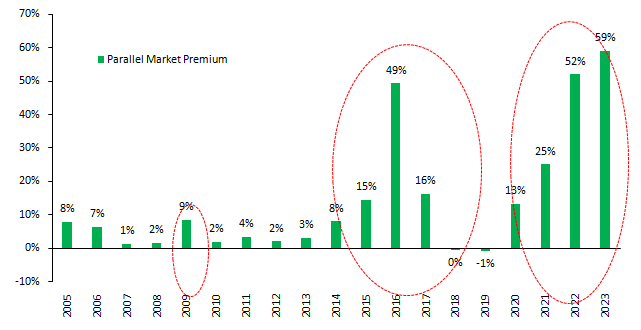

After the initial optimism surrounding the unification of the Naira, with the disappearance of the gap between the official and parallel market exchange rates, sentiments have turned pessimistic as trading activity in the Investors & Exporters (IE) window has remained stagnant, and parallel market premiums have widened to 20% with the value gap at N170/$. Alongside a steady decline in gross external reserves to $33.9 billion, concerns have heightened about the outlook for the currency and its knock-on effect on domestic prices and citizen welfare. Granted that FX unification was not an end to itself, but rather a means towards restoring improved forex liquidity flows and restoring capital flows, the initial signs have not inspired confidence that a resolution to the lingering FX crisis is at hand.

Given the speed within which the Naira floatation was executed without any concrete arrangements on bolstering dollar supply, focus has shifted to this unresolved item given thin dollar liquidity within the official segment (daily trading has averaged $106 million versus $110 million prior to unification) amid signs of fresh weakness at the parallel market. Without direct attempts to stem the tide, the temptation to return to the old ways of managing things might look attractive which might blow away the current opportunity.

What further steps are required to stabilise the emerging situation over the near term and what concrete policy adjustments should follow for Nigeria to have a more sustainable approach to exchange rate management? In what follows, we briefly review the Naira float policy, provide some historical context to exchange rate regimes—highlighting the expected benefits and potential pitfalls of fixed and floating systems—and provide some recommendations on how Nigerian policymakers should look to approach FX management in the near and medium term.

Naira Floatation: Shock Therapy in the Face of Fundamental Deterioration

For the fifth time in Nigeria’s post-independence history (after similar moves 1986, 1995, 1999-2000, 2017), Nigeria’s policymakers have elected to abandon a hard nominal exchange rate peg (with the most recent one set at N461/$) in the face of depleting external reserves. Interestingly, the CBN announcement on the seismic shift in policy did not provide any justification for the decision nor an admission that the old peg arrangement had failed.

This would suggest it was not an innate desire or willingness to change but rather a loss of ability amid growing political pressure following the suspension of the CBN governor. Indeed, only as recent as May 2023, the CBN organised a conference where many participants (including the present top brass at the apex bank) ‘celebrated’ one of the many confusing policies (RT200) of the old FX regime which has now been scrapped. Thus, it is more likely that a shift in political leadership catalysed an opportunity for the CBN insiders to save face by quickly returning to fundamentals as the basis for FX rate management.

A look at the fundamental data reveals the existence of large imbalances in Nigeria’s external accounts occasioned by a mix of structural shifts and policy missteps by the CBN as the bane of the present FX woes. Between 2005-2013, Nigeria enjoyed a ‘structural surplus’ in the export and imports of goods and services (see Figure 1) primarily on account of higher oil export revenues due to stronger oil prices as oil production remained roughly static around2-2.2mbpd. This surplus exceeded $20 billion annually in the early part of the period (2004-2008) which allowed substantial external reserve accretion (peak $62 billion in September 2008) before moderating to $10-15 billion in 2010-2013 period.

Figure 1: Nigeria’s export import balance 2005-2022 (USD’billion)

Source: CBN

By design, the CBN has a fiat ownership of export petrodollars (a flaw at the heart of Nigeria’s FX architecture which we shall see later), which allows the apex bank to situate itself at the heart of FX management during boom times with the ability to determine to a large extent the price (exchange rate that most people get dollars) and quantities (USD allocation or who can get dollars). The latter being a derivative of the former as the readily available ‘stronger’ CBN rate ensured that its price set the tone for other FX segments. As a result, the official USD market was large enough relative to the non-official USD market so much so that the CBN began supplying dollars to retail end-users via Bureau-De-Change operators.

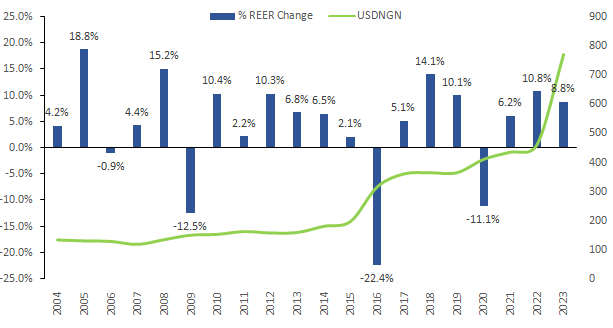

The large crude oil flows resulted in the adoption of a ‘defacto’ policy of exchange rate stability as the basis for monetary policy even though several CBN governors would publicly declare inflation targeting as the ‘dejure’ basis for monetary policy1. This commitment to nominal exchange rate stability also underpinned real exchange rate appreciation over the period. For context, while the nominal exchange rate weakened 16% (-1.8% per annum) over the 2005-2013 period, the Naira appreciated 55% (+6% per annum) in real terms which as we shall see had profound implications for non-oil exports and service imports.

Figure 2: Nominal USDNGN and annual change in the real effective exchange rate

Source: CBN, Bruegel *May 2023

But first we turn our attention to dollar supply trends within the Nigerian economy. As noted earlier, at the height of the oil boom in the mid-2000s, the scale of the oil inflows and Nigeria’s shallow and less integrated financial markets (Nigeria had no bond market until 2007) implied that the CBN dominated the FX market accounting for between 60-70% of the total market. However, this dominance in terms of USD inflows declined to under the 50% in 2007 when CBN flows totalled $36 billion relative to non-CBN inflows of $38 billion implying that there was more USD coming into the Nigerian economy via autonomous sources than through the CBN channel.

This gap would widen in the coming years and at one point was more than double CBN inflows in 2010 ($63 billion vs $27 billion) before peaking at over $103 billion in 2013 (when CBN flows came to $41 billion). Essentially, the CBN dominance of the official market was an illusion helped by the commitment to exchange rate stability via a combination of tight Naira interest rates and relaxed FX controls. This allowed the CBN maintain the illusion of control that it determined prices within the official segments and could control the market.