- Details

- By Agora Policy

- Policy Memo

- Hits: 894

By Babajide Fowowe and Muhammed Shuaibu | As Nigeria prepares to usher in a new administration, the state of the economy remains a key point of interest. This owes largely to the myriad of economic challenges the country faces, as highlighted in the Agora Policy Report on the economy1. A critical issue that the incoming administration has to grapple with is how to revamp the economy, and quickly.

The key macroeconomic statistics do not paint a rosy picture. The inflation rate rose to 22.04% in March2023. Real GDP growth rate fell from 3.40% in 2021 to 3.1% in 2022. The latest statistics show that 40.1% of Nigerians are poor, while unemployment is 33.28%.Despite favourable global oil market conditions, domestic oil production shocks have dampened oil revenue inflows and have drastically increased the cost of the petrol subsidy, thereby widening Federal Government’s fiscal deficit. This has led to crowding-out of critical spending on social services and infrastructure.

While there are numerous development challenges and actions required at all levels of government, this memo focuses on three key policy actions at the Federal level: fiscal, monetary and trade policies. It is our considered opinion that the incoming administration needs to undertake fast, coordinated macroeconomic policy reforms on these three fronts. These policy actions or economic reforms must be predicated on inclusion, transparency and accountability.

2 Fiscal Policy

2.1 State of Affairs

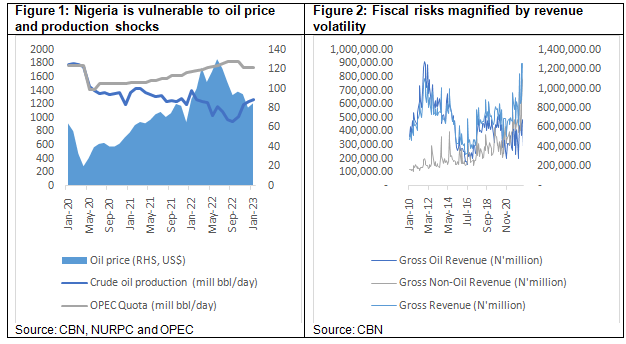

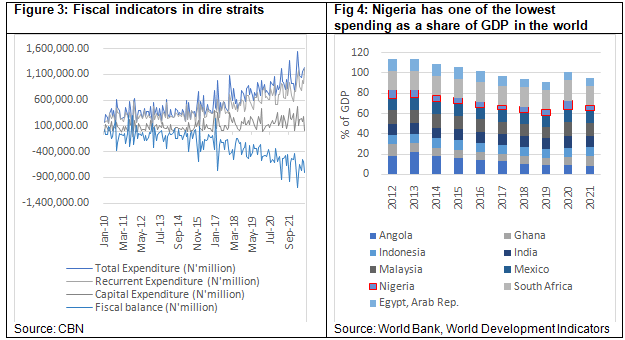

Since the 1970s, Nigeria’s fiscal profile has been tied to the oil sector. Despite the high oil prices in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, Nigeria’s oil production has been very low. Oil production started falling from 1.799 million barrels per day (bpd) in January 2020 and reached a trough of 937,766 bpd in September 2022 (Figure 1). Since April 2020, the country’s oil production has consistently been below its OPEC quota, and the production shortfall reached a peak of 892,234 bpd in September 2022 (Figure 1). These drastic falls in oil production have come amid a surge in oil prices, with oil prices reaching an all-time high of $130 per barrel in June 2022 (Figure 1). The overall performance of federally-collected revenue has been quite poor, exhibiting heightened volatility in line with global crude oil price movements. FG’s gross oil revenue inflows were N329.984 million in January 2022 but fell to N199.082 million in February 2022. It then started rising and reached a peak of N485.068 million in August 2022 (Figure 2).

The performance of federally-collected gross non-oil revenue exhibited relatively larger swings in 2022. It dropped from N485.645 million in January to N393.012million in March but rose to N805.854 million in July before declining to N616.420 million in September 2022. While the modest improvement could be a reflection of improvements in tax collection, the non-oil revenue generating capacity remains far below its potential especially given the country’s significant spending needs. As pointed out in the Agora Policy report on the economy, many revenue-generating agencies either fail to remit any revenue, or remit a very small fraction to the government. This is a serious problem that needs to be addressed because it deprives the FG of the much-needed revenue. Moreover, the action of such agencies is in violation of the Fiscal Responsibility Act which mandates revenue-generating agencies to remit 80% of their operating surpluses to the Consolidated Revenue Fund and retain 20% in their reserve fund.

Nigeria’s spending needs have maintained an upward trend since 2010 (Figure 3). However, when compared to other countries, the quantity and quality of spending is low (Figure 4). Figure 3 shows that total FGN spending is largely dominated by recurrent spending with a limited share going to capital expenditure. The average share of monthly recurrent spending in 2021 was about 79% compared with 21% for capital expenditure. Between January and September 2022, average recurrent expenditure was about 84% while capital expenditure was 16%.

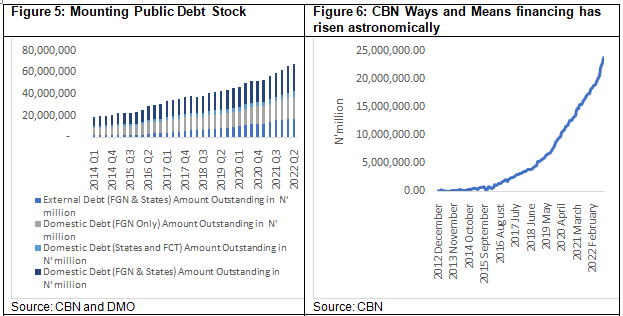

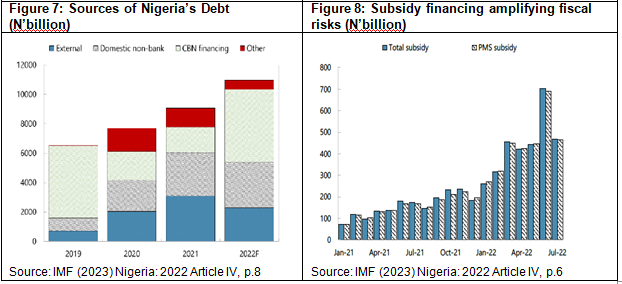

The FG has consistently run a fiscal deficit over the last decade but this has worsened in recent times due to a combination of lower revenue inflows and high fuel subsidy payments (Figure 8). The high fiscal deficit financing need has led to a steady increase in FG’s total public debt stock. FG's domestic debt doubled from N7.18 trillion in Q1 2014 to N14.534 trillion in Q1 2020. Domestic debt further increased to N20.14 trillion in Q1 2022. It is important to note that the official domestic debt statistics does not include ways and means borrowing from the CBN. The Agora policy report on the economy2 highlighted the fact that the FGN’s ways and means borrowing from the CBN had reached N18.8 trillion in March 2022. If this is added to the official domestic debt figures, then total domestic debt would be N38.94 trillion in Q1 2022. The Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) ways and means financing has overshot the statutory limit. Since 2005, FG has increased borrowing through the ways and means financing from CBN (Figure 6). This has been further increased in recent times due to external elevated borrowing costs in the Eurobond market (Figure 7).3

On the external side, the combined outstanding debts of the FG and state governments increased from N8.3 trillion in Q2 2019 to N11.3 trillion in Q2 2020. By Q2 2021, the outstanding external debt stock increased further to N13.7 trillion and rose further to an all-time high of N16.6 trillion in Q2 2022 (Figure 5).

2.2 Immediate Fiscal Reforms

2.2.1 Boosting oil revenue: The drastic fall in oil revenue has been as a result of the double whammy of lower oil production and petrol subsidy. The government needs to take decisive action to address these two critical issues.

Ending oil theft: Addressing the drastic fall in oil production requires urgent action to end oil theft in the oil producing areas. This would require strong determination from the government and crucially, cooperation from host communities and the security agencies. The government needs to review the security architecture in the oil producing areas and give clear instructions about ending oil theft. In addition, both the Nigeria Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC) and Nigeria National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC)Limited should be given clear oil production and exporting targets, and be held accountable when these are not met.

Removal of the petrol subsidy: The use of a strategic communication team to engage the public and other critical stakeholders on the benefits and costs of removing the subsidy would be required for the public to buy into this policy measure. At the same time, detailed plans of how funds are saved from subsidy removal need to be extensively discussed and disseminated to the general public to increase trust as a social capital. The savings from the fuel subsidy could be used to scale up short-term direct cash transfers to the poorest and most vulnerable groups in the country. Prices of petroleum products should be market-determined rather that regulated by the government.

2.2.2 Boosting non-oil revenue: There is a need to address the nation’s dismal tax revenue to GDP ratio. The FIRS has done well in recent times by increasing revenue generated from N6.4 trillion in 2021 to N10.1 trillion in 2022, thereby crossing N10 trillion in revenue for the first time. However, for the size of the economy, government revenue and expenditure are grossly inadequate to effectively drive policy, enhance economic growth, lower poverty, and achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This would require two critical actions on boosting non-oil revenue:

Tax reforms and domestic revenue mobilisation: There is an urgent need to broaden the tax net to capture the formal and informal sectors not in the existing tax net. For the formal sector, a first step would be to properly capture and tax high net worth individuals and large corporations. Also, FIRS needs to work closely with the NBS to identify small and medium scale enterprises (SMEs) and ensure they pay taxes appropriately. Some simple incentives and an amnesty period, following which appropriate sanctions will be meted out, can be given to ensure quick compliance. It would be crucial to continuously communicate the issue of tax reforms to the citizens to gain public confidence in the system. In addition, leakages from taxes collected by non-state actors need to be eliminated.

Full compliance with the Fiscal Responsibility Act: The Fiscal Responsibility Act mandates revenue generating agencies to remit 80% of their operating surpluses to the Consolidated Revenue Fund and retain 20% in their reserve fund. There are many revenue-generating agencies that either fail to remit any revenue or remit a very small fraction to the government. The Fiscal Responsibility Act should be amended to set strict penalties for agencies that fail to remit their stipulated operating surpluses. Also, there is the need to stop funding revenue-generating agencies from the federal budget.

2.2.3 Improving the budget implementation framework. This entails strengthening the zero-based budgeting framework by ensuring that budget preparation starts on time. There is an urgent need to end “drip-feeding” which has inhibited the completion of critical capital projects and perpetuated the “ongoing project” syndrome. This comes at zero cost to the key agencies such as the Federal Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning and the Budget Office of the Federation. Increased budgetary provisions should be given to capital expenditure. There is also the need to increase the percentage of the budget that goes to capital expenditure and the necessity of trimming recurrent expenditure.

3 Monetary Policy

3.1 Monetary Policy Developments

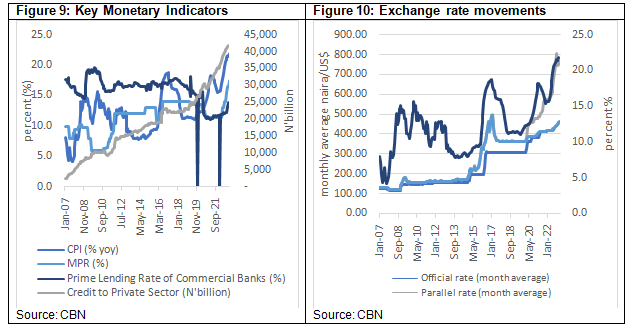

Similar to other central banks around the world, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has tightened its monetary policy stance to tame rising inflation. The CBN raised the monetary policy rate by a cumulative 5% in 2022 and also increased the cash reserve ratio from 27.5% to 32.5%. Despite these tightening measures, the monetisation of the fiscal deficit and other quasi-fiscal activities such as the intervention programmes have expanded the growth of credit and thus contributed to inflationary pressures. The year-on-year composite price index (CPI) increased from 15.6% in January to 18.6% in June and to 20.8% in September 2022. It moderated marginally to 21.3% in December 2022 before rising again to 21.91% in February 2023. The obvious disconnect between fiscal and monetary policy has heightened macroeconomic risks and vulnerabilities. The weak transmission mechanism of monetary policy is a combination of poor policy coordination and focus of the CBN on economic growth rather than on inflation(Figure 9).

Exchange rate management has remained at the front burner of policy discussions. This is due to the complete exchange rate pass-through to domestic prices in Nigeria. Nigeria currently operates several exchange rate windows, often at varying rates (Figure 10). This has created arbitrage opportunities for speculators in the foreign exchange market. The official exchange rate was N416/$ in March 2022 and had increased to N461/$ in February 2023 (Figure 10). The parallel market exchange rate has continued to diverge from the official rate. In January 2022, the parallel market exchange rate was about N570/$ and had increased to about N761/$ in February 2023. The CBN also created an Investors and Exporters Foreign Exchange (IEFX) window to give genuine importers and exporters access to foreign exchange. This IEFX rate closely mirrors the official exchange rate but is still below the market-based parallel exchange rate. The average IEFX rate in 2022 was about N428/$ and it had increased to N461/$ in January 2023.

- Immediate Monetary Reforms

- Enhance the coordination of fiscal and monetary policy to reduce frictions and counteractive policy goals. The government should strengthen the Fiscal-Monetary Coordination Committee to ensure that the monetary authority (CBN) and the fiscal authority (Federal Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning) optimally coordinate policies to ensure the gains from fiscal and monetary reforms are maximized.

- Restore monetary policy focus back to its price stability mandate, taming inflationary pressure and strengthening the monetary transmission. The CBN should focus on its core mandate of maintaining price stability. The CBN should set clear and realistic targets for inflation, and a timeline for achieving these targets. Addressing supply-side bottlenecks such as trade restrictions on critical intermediates that increase the cost of doing business. The CBN will have to restore the credibility of the MPR such that bond yields and lending rates are reflective of the monetary policy rate (MPR).

3.2.3 The removal of the current multiple exchange rate windows being operated by the CBN. This would make the exchange rate market-determined and mitigate speculative pressures that fuel arbitrage conditions in the market. This would further inspire confidence from domestic and foreign investors.

3.2.4 Putting an end to ways and means financing of FGN expenditure. This would curtail the growth of the money supply and thus curtail inflationary pressure. Part of this will involve the CBN helping the FG to properly forecast its revenue as well as helping the FG, on a technical level, identify potential sources of revenue. A strategy will also need to be developed to manage the current stock of FG’s debt at the CBN.

4 Trade and Investment

4.1 State of Trade and Investment

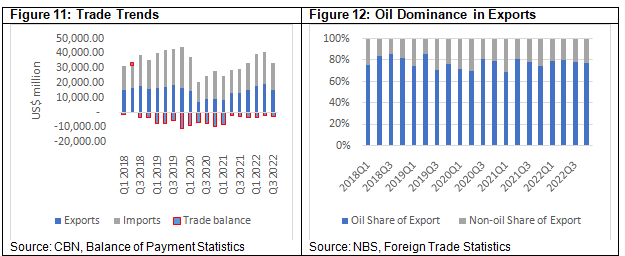

Nigeria has one of the largest economies in Africa, with a significant trade volume. However, the country’s trade profile has historically been dominated by oil exports, which account for a large share of the country’s foreign exchange earnings (Figure 12). The low level of trade diversity and the need to reduce over-reliance on oil exports in Nigeria has remained a major concern for governments over time. Figure 11 indicates that since Q1 2020, with the exception of Q2 2021, Q2 2022 and Q4 2022, imports have exceeded exports, resulting in trade deficits for most of the period.

While Nigeria’s export shave largely been dominated by oil exports, the trend of imports depicts a different picture. Non-oil commodities dominate Nigeria’s total imports as they increased from 70% in 2018 to 84% in 2019 and 77% in 2020, before falling to 69% in 2021 to 59% in 2022 (Figure 13).In terms of trade in services, Nigeria’s performance is quite limited as services import dwarfs services export (Figure 14). The average services import in 2018 was about 87% and increased to 89% in 2019 then dropped to 81% in 2020. By 2021, it dropped marginally to 80% and remained at the same average level in the first three quarters of 2022.

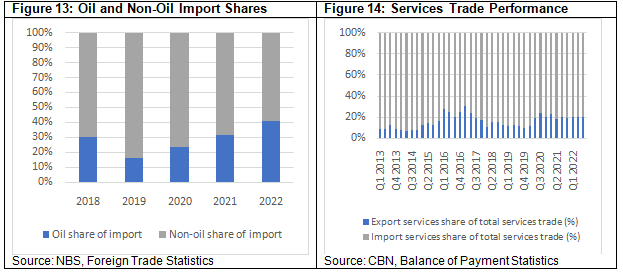

The volatility of capital inflows has persisted over the last decade. FPI inflows in the fourth quarter of 2018 was US$3,935 million but dropped significantly, translating to an outflow of US$3,788 million in the fourth quarter of 2019. By the fourth quarter of 2020, FPI outflow slowed down to US$477 million and even recorded significant improvements with inflows of US$1,926 million recorded in Q1 2021, before dropping to outflows of US$3,012 million in 2021Q4. FPI remained positive in the first three quarters of 2022 recording a drop from US1,542 million in 2022Q1 to US$1,001 million in 2022Q3. In terms of FDI inflows, the fluctuations have been relatively lower than FPI as it rose from US$59 million in 2018Q4 to US$248 million in 2019Q4and US$439 million in 2020Q4. This positive trend reversed by the fourth quarter of 2021 as FDI inflows dropped significantly to US$42 million and for the first time in over a decade recorded an outflow in 2022Q1 (US$323 million) and 2022Q2 (US$1,537 million) before a positive rebound of US$726 in the third quarter of 2022.

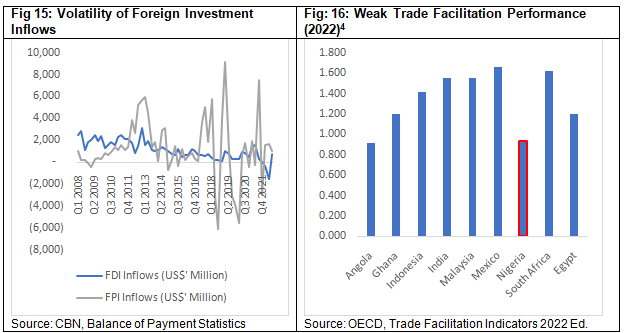

One of the major issues that have impeded trade performance and thus diversification in Nigeria is the weak trade-related infrastructure. Having in efficient or inadequate systems of transportation, logistics, and trade-related infrastructure can severely impede a country’s ability to compete on a global scale.5 Based on the 2022 OECD trade facilitation performance indicator, Nigeria performs poorly (0.930) relative to regional peers such as Ghana (1.200), South Africa (1.625), and Egypt (1.200). The trade facilitation performance indicator is composed of a set of variables measuring the extent to which countries have introduced and implemented trade facilitation measures in absolute terms, but also their performance relative to others. The indicator takes values from 0 to 2, where 2 indicates the best performance that can be achieved.6

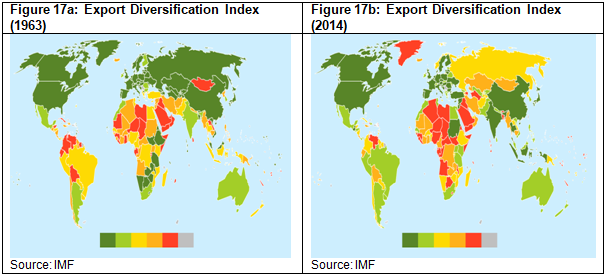

The lopsided structure of Nigeria’s trade performance over time is linked to low trade diversity. Although this has remained at the forefront of various development policy plans, weak implementation and poorly coordinated macroeconomic policy and structural reforms have constrained trade diversification. For example, Nigeria has used several trade restrictions mainly to protect domestic industries and spur domestic productivity. However, this has not achieved the planned objectives as domestic firms remain largely uncompetitive due to structural rigidities tied to the inadequate soft and hard infrastructure. Comparatively, as shown in Figures 17a and 17b, Nigeria’s export diversification has worsened over the last five decades. At 3.74 in 1963, it increased to 4.65 in 1970 and 6.15 in 1980. By 1990 it had reduced marginally to 5.99 before rising to 6.04 in 2000 and then dropping again to 5.54 in 2010. In 2014 Nigeria’s export diversification index was 5.62 which was far below the performance of other countries like South Africa (2.59), Egypt (2.65), India (2.16), Indonesia (2.21) and Mexico (2.43).7It is important to note that higher values correspond to lower export diversification while lower values correspond to high export diversity.

4.2 Immediate Trade and Investment Reforms

4.2.1 Replacement of import bans with import duties. The use of tariffs rather than the existing import bans would spur the domestic productivity of firms, especially those that rely on the import of intermediates that are affected by the import prohibition. This has to be done in a coordinated manner between the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment, Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning, and the Nigeria Customs Service.

4.2.2 Development of regional industrial hubs and transport infrastructure through PPP arrangements. FGN should prioritise the development of industrial hubs and export processing zones as well as the delivery on critical infrastructure which support international trade, such as ports, roads, and telecommunications networks. In view of obvious budgetary constraints and current revenue shortfalls, the government should seek partnership with the private sector. This could help enhance efficient service delivery and reduce trade costs, thereby making it easy for domestic firms to integrate in domestic and regional value chains.

4.2.3 Reopening all closed borders and removing all food trade restrictions. These have hurt prices and have not led to the expected increase in domestic productivity. The government needs to prioritise the development of a goods and services export strategy in collaboration with the subnational governments. Such a strategy should focus on labour intensive sectors, and should clearly identify priority sectors and potential markets by leveraging Nigeria’s global network of diaspora and consulates.

4.2.4 Creating a conducive environment for attracting foreign investment. The rise in foreign investment outflows needs to be addressed by sending positive signals to foreign investors. The exchange rate needs to be market-determined. Also, security, banditry, kidnapping and insurgency need to be adequately tackled to send positive signals.

4.2.5 Providing incentives for export-oriented firms especially in the non-oil sectors. In order to leverage on the enormous market opportunities created by the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) agreement, there should be a gradual reduction of import tariffs on intermediate products used by domestic firms that export or plan to do so. At the same time, the discretionary import duty waiver allocation system needs to be replaced with a clearly defined industry-wide incentive system that supports export-oriented firms.

Conclusion

The Nigerian economy has significant potential but faces several challenges. Nigeria is the largest economy in Africa, with a large and growing population, abundant natural resources, and a strategic location. However, the country has struggled with economic diversification and over-reliance on oil exports, which has made it vulnerable to external shocks. The country also grapples with some structural challenges, including poor infrastructure, limited access to credit, and weak institutions. These issues have hindered economic growth and made it difficult for businesses to thrive in the country. This note highlights some of the key challenges facing the Nigerian economy in the context of fiscal, monetary and exchange rate management, trade and investment policies. It also prescribes urgent actions on those three critical fronts.

*Professor Fowowe and Dr. Shuaibu teach Economics at the University of Ibadan and the University of Abuja respectively.

[1]https://agorapolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Updated-Digital-Version.pdf

[2] https://agorapolicy.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Updated-Digital-Version.pdf

[4]http://compareyourcountry.org/trade-facilitation/en/0/default/all/default/2022

[5]https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/trade-facilitation-and-logistics

[7]https://data.imf.org/?sk=A093DF7D-E0B8-4913-80E0-A07CF90B44DB

Read more: Urgent Policy Actions on Fiscal, Monetary and Trade Fronts

- Details

- By Agora Policy

- Policy Memo

- Hits: 313

By Adebayo Ahmed | Jobs are one of the foundations for a stable society and key to improvements in quality of life. Unfortunately, unemployment is one of Nigeria’s major challenges today. Beyond the negative impact on human welfare, unemployment is gravely implicated in Nigeria’s other pressing challenges, especially low productivity, poverty and insecurity. It needs to be tackled aggressively and comprehensively, not in the current tokenistic and uncoordinated fashion.

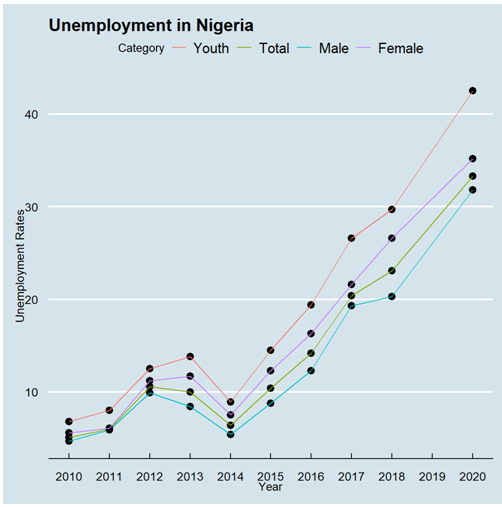

Fig 1: Unemployment Rates. Source: NBS

In the last decade Nigeria has struggled to create enough jobs to meet up with the constant flow of people entering working age. Since 2010 the unemployment rate has been on an upward trajectory rising from 5.1% in 2010 to the last pre-covid estimate of 23.1% in 2018, with the situation worse for women. Unemployment rate rose to 33.3% during COVID, combined with a much-reduced labour force participation rate. There has been little official information since. Although the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) claims to be working on an improved methodology for measuring unemployment, all we can say at this point is that unemployment is likely still high and at an undesirable level. The situation has been particularly worse for young people who, as at 2020, faced an unemployment rate of over 40%. There is little doubt that this rising unemployment is linked to increasing restfulness and disenchantment among the youth.

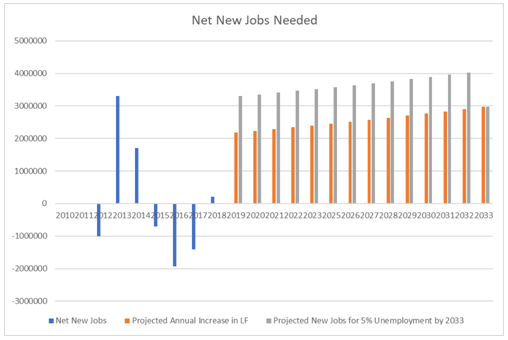

Fig 2: Net new jobs created and needed. Source: NBS, Author’s Calculations.

Given that the population, and hence the labour force, keeps growing, the challenge of reducing unemployment is therefore all about creating more new jobs than there are people entering the labour force. At the very least, to keep unemployment from rising, enough net new jobs need to be created to at least employ the majority of net new entrants to the labour market. What does this mean in the Nigerian context? Based on a labour force of about 90 million1 prior to COVID in 2018, about 2.5 million net new people enter the labour force every year. Which means the economy would have to create at least 2.5 million new jobs a year on average just to keep the number of the unemployed from rising. If we wanted to get the unemployment rate to a healthier five percent by 2033, and we assumed that the labour force grew at the same rate as population growth, then by our calculations, we would need to be creating at least 3.6 million net new jobs a year2. Given that between 2010 and 2018 we only created on average 21,757 net new full-time jobs a year then you can see clearly that we have a problem3. In fact, as shown in Figure 2, 2013 is the only year in the last decade when we actually produced over three million net new jobs.

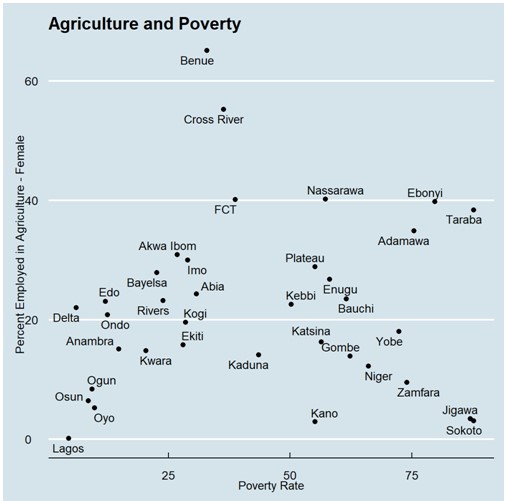

Fig 3: Employment in Agriculture vs Poverty Rates across states (Male and Female).

Source: NBS Living Standards Survey 2018.

If we add the caveat that the jobs created have to be good enough to allow people have a meaningful quality of life, then the challenge is even more difficult. One of the features of current employment, especially in subsistence agriculture, is that some of the jobs do not result in enough income to actually lift the employed persons out of poverty. As observed in Figure 3 above, some of the states with the largest employment in agriculture also happen to be the states with the highest poverty rates. Many of these people are employed but are still living in poverty despite their employment. For example, although Sokoto State had an unemployment rate of 14.3% in 20184, majority of the people were employed in (presumably) subsistence agriculture (51% of males and 3% of females). The implication being that over 87% of households were still living in poverty. In essence, it is not just jobs that are needed but decent jobs.

Limits of current approaches

The current approaches by government to tackling unemployment, while sometimes having merit, have failed to resolve the problem. This is largely because the majority of the approaches cannot reach the scale of what is required.

The first of the common approaches is direct government employment. This is particularly popular at the state and local government level, even if the Federal Government is not left out. Although it is easy to argue that the country needs more police personnel, more doctors, and more teachers, it is clear that government employment alone cannot solve the unemployment challenge. It is almost unfathomable to imagine the federal, state, and local governments combined being able to employ anywhere close to three million workers each year. This is even before you take into account their financial constraints. In fact, according to some reports, the entire Federal Government only employed about 720,000 people as at 20205. The ILO estimates that there were only about 2.12 million people employed in the public sector in Nigeria in 2020. Given the scale of the challenge, it is unsurprising that government employment has not worked in resolving the challenges.

Fig 4: Q3 2018 Unemployment by Educational Category. Source: NBS

A second common approach is the skills-acquisition driven approach. The summary of this approach is that if you teach people some skills, such as carpentry or tailoring, then that should automatically result in employment. For instance, a cursory look at the activities of the National Directorate of Employment (NDE) shows that most of its programmes are essentially skills acquisition programmes. However, unfortunately, in reality skills do not necessarily mean jobs. For instance, in 2018 the unemployment rate for people with post-secondary education at 29.8% was higher than for people with no education at 21.8%. Similarly, as is clear in Figure 4

above, people with only primary education had a lower unemployment rate than people with NCE/OND/Nursing certificates even though they presumably have more skills. Although there are issues such as skills mismatch and selectivity in employment, and there is still significant room for certification for specific skills, it does signify that more skills alone will not necessarily solve the unemployment challenge.

The third, and more recent approach is that of social investment or social transfers as signified by the expansion of programmes such as trader-moni or other direct cash support schemes popular at state and local government level. As with the case with direct government employment, the scale of the challenge means that this is unlikely to be a sustainable approach. According to the NBS6, only between 10,000 and 20,000 thousand were enrolled in the governments N-Power programme in each state as at 2018. The FG stated that it planned to raise the total number of beneficiaries to one million in 2020. The GEEP programmes have similar statistics. Although you can argue about the merits or demerits of such programmes, what is clear is they are not creating, and probably cannot create, the 3.6 million net new jobs a year to tackle Nigeria’s unemployment challenge.

Prescriptions / Recommendations

In thinking of a coherent strategy to tackle the unemployment challenge, we need to take a step back and understand what exactly jobs are. Jobs are essentially the contribution of individuals to economic activity. Which means if you want to see faster job growth then you must have faster economic growth. However, as we learned during the growth episodes in Nigeria in the early 2000s, growth alone does not imply jobs. There can be jobless growth and job-led growth. Specifically, what we need is growth in labour-intensive sectors.

For instance, growth in petrochemical refining or car assembly is unlikely to provide as much jobs per unit of output compared to growth in the more labour-intensive textiles sector. Even within the textile value chain, growth in the relatively capital-intensive part of the chain that converts cotton into fabric, is unlikely to create as many jobs per unit of output as the more labour-intensive part that converts fabrics into clothing. There needs to be a specific focus on engineering sustainable growth in these labour-intensive segments of various value chains. Given the scale required—3.6 million net new jobs a year—the output of this engineered growth will likely need to be targeted at markets much larger than Nigeria’s.

In summary, on a macro level the most likely path to job creation in Nigeria at the scale required, is to engineer growth in labour-intensive portions of value chains for export to large markets. What does this mean in terms of specific policy actions?

From a broader economy-wide perspective, it means:

- Resolving broader macro-economic challenges that limit growth across the board. This includes resolving the dysfunction of multiple rates in the foreign exchange market, and re-focusing the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) on its mandate of keeping inflation at optimal levels.

- Targeted infrastructure spending in particular areas that increase the competitiveness of Nigeria’s exports. This would include electricity, transport, and telecommunications investments in export processing zones. For instance, India’s new foreign trade policy 20237 designated four “towns of export excellence” that will get priority access to export schemes and investments.

- Developing and implementing an export-driven trade policy for labour-intensive value addition for export sectors. This could include fast-tracking implementation modalities for participating in the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), fast-tracking trade agreements that grant Nigerian export access into large markets, and reducing tariffs completely or introducing transparent reimbursement schemes for imports of intermediary goods for value addition.

- Developing a strategy to utilise our large diaspora network as well as our network of embassies and consulates to get Nigerian products into markets around the world.

- Re-organising our technical and non-academic learning protocols to improve on specific skills in areas critical for improvements in competitiveness of targeted sectors. This could include trade schools aimed at providing necessary skills for particular sectors. For instance, if the garment sector is a targeted sector it would include starting up or improving on technical schools and certification for fabric cutting or clothing design software.

- Developing and implementing a strategy to reduce the costs of logistics, both financial and non-financial. This could include things like “trusted firm” schemes that allow customs and security procedures take place inland, at dry-land ports for instance, to by-pass time-consuming procedures at official ports.

- Investing in certification and export processes training in partnership with targeted destination countries to ease the cost of accessing external markets, specifically for SMEs that do not have the financial clout to do this on their own. As has been argued by some economists, SMEs tend to employ more people per output produced. Hence, ensuring SMEs participate in an export push can amplify the scale of job creation.

To improve the decency and capacity of agriculture jobs to provide a minimum income and quality of life, this will mean:

- Developing and implementing a productivity growth strategy for agriculture that will target improvement in yields for subsistence farmers. This will include strategies for improved seed varieties, improved crop choice, irrigation infrastructure, crop-specific weather and market information, crop insurance and social protection etc..

- Developing and implementing a market development and financial innovation strategy for agriculture to ensure that crops have access to markets and off-takers, and predictable and flexible revenue streams.

Finally, to take advantage of the growing global trends in remote work especially in ICT and other export services, this will mean:

- Fast tracking the implementation of the broadband plan to improve the competitiveness of Nigeria’s remote workers.

- Developing a fair, transparent, and competitive taxation policy for remote workers that reduces their incentives to emigrate to tax havens and that incentivizes other skilled workers to opt for Nigeria.

- Working with states to develop livable safe spaces that incentivize skilled workers to remain in Nigeria.

Conclusion

The size of the Nigerian population and the scale of the unemployment challenge implies that piecemeal and uncoordinated approaches are unlikely to make a significant impact. If Nigeria desires to get unemployment down to 5% by 2033, it needs to create 3.6 million jobs a year. To achieve this, it needs a scalable strategy. Given that jobs are simply part of the process of generating economic activity, then Nigeria needs to engineer growth in labour-intensive sectors in general, and labour-intensive parts of value chains in particular.

[1] National Bureau of Statistics Labour Force Survey Q3 2018

[2] A labour force growth rate of 2.41% implies that by 2033 the labour force would have about 126m people. This means to have 5% unemployment then about 120m people need to be employed. Which in turn implies that between 2018 and 2033, about 54m new jobs need to be created. This amounts to about 3.6m net new jobs a year on average.

[3] National Bureau of Statistics Labour Force Surveys 2010 - 2018

[4] NBS – Q3 2018 Unemployment by States

[5]https://leadership.ng/ippis-fg-trims-civil-servants-to-720000/

[6] NBS 2020 Social Statistics in Nigeria

[7] https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1912572

- Details

- By Agora Policy

- Policy Memo

- Hits: 441

By Joe Abah | Since the return to democratic rule in 1999, several efforts have been made to improve governance and to reform public service in Nigeria. While some of these efforts have recorded some results, some have not. The next administration needs to sustain and accelerate the pace of governance and public service reforms to improve service delivery, citizens’ welfare and overall national development.

In defining governance, we will adopt the definition of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation, which defines the concept as “the provision of political, social and economic goods that citizens have a right to expect and that a state has the responsibility to deliver.”1 We will simply define Public Service Reforms as the deliberate actions to continuously improve the structures and processes through which public goods are delivered to citizens.

The trajectory of governance reforms in Nigeria can be roughly divided into three main developmental phases: Foundational; Process-Focused; and Citizen-Centred. We have attempted to delineate the phases with dates, but they do not necessarily all fit neatly into the suggested dates. The delineation by dates is largely illustrative to show a progression in focus.

Post-1999 Reforms, Progress and Challenges

The foundational phase between 1999 and 2007 focused on establishing rules of behaviour and accountability in the public service, being that military rule, which was in place before 1999, operated a command-and-control system that is alien to democratic rule.

The reforms put in place included the establishment of a due process regime and the enactment of the Public Procurement Act in 2007; anticorruption legislations and the establishment of anticorruption agencies; consolidation of salaries and emoluments and the monetisation of fringe benefits; reform of the pensions system from an unaffordable defined pension system to a contributory pension system; and the computerisation of payroll through the Integrated Payroll and Personnel Information System (IPPIS). Most of these reforms were necessarily focused on the operations and mechanics of the public service itself. Apart from telecommunication reforms, pension reforms and some high-level arrests by the anticorruption agencies, many of the reforms did not directly affect the ordinary Nigerian.

The second phase, the process-focused phase between 2008 and 2015, started to be more outward-looking. It saw the commencement of efforts to improve the way things are done and tighten loopholes observed in the foundational phase of the reforms. Some of the reforms undertaken include privatisation of the power sector; justice sector reforms; electoral reforms; initial efforts at improving identity management; Public Financial Management reforms (including the introduction of the Treasury Single Account and the Government Integrated Financial Management Information System, GIFMIS); reform of the banking sector; reform of tax administration; and efforts at improving transparency, with the enactment of the Freedom of Information Act 2011 and the establishment of the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI).

In the third phase from 2016, particularly with the rise in social media usage, the emphasis has started to shift to the experience that citizens have when they encounter government. Some of the reforms undertaken include the ‘Ease of Doing Business’ regime that aims to make it easier to register businesses, obtain business visas, get licences and permits, and facilitate trade. Efforts have also been made to improve consumer protection and improve the country’s resilience to large-scale infectious diseases like Ebola and COVID-19.

It is important to reiterate that the taxonomy used in the preceding paragraphs to delineate the various phases of the reforms is not linear and sequential. For instance, some citizen-focused reforms, such as the initiative against fake and substandard drugs, started well before 2007. Since the introduction of IPPIS in 2006, efforts have subsequently been made to link it to Bank Verification Numbers and National Identity Numbers. Similarly, the national identity management database, established in 2007, did not expand significantly until it was linked to mobile phone numbers in 2020.In essence, reforms are a continuous process. There is no silver bullet which, once fired, obviates the need for further reforms.

Similarly, the various reform efforts have not resulted in linear and sequential improvements. For instance, Nigeria’s ratings on the ease of doing business have improved. Between 2016 and 2020, Nigeria moved up 39 places in the World Bank Ease of Doing Business rankings and was twice recognised as being one of the top 10 countries driving ease of doing business reform.2Aggregate budget performance improved to an impressive 98% in 20203 and the national identity database has expanded from seven million records in 2015 to 97 million records in March 2023.4

Conversely, the gains made in tackling fake and substandard pharmaceuticals have waned, with unapproved pharmaceuticals and sexual enhancement drugs openly offered for sale. The ratings of the country’s anticorruption efforts have been unimpressive since its highest ranking of 136 in 2014. Nigeria is now ranked 150 out of 180 countries.5 Constant electric power remains elusive, and petrol is still not freely available. Also, efforts to reduce the cost of governance have been largely in the realm of rhetoric rather than concrete action.

The Oronsaye Report, submitted in 2012, stated that Nigeria had 547 federal agencies, parastatals and commissions. As of 2021, the Budget Office of the Federation declared that Nigeria had 943 ministries, departments and agencies and 541corporations owned by the

Federal Government.6 Rather than reducing the number of agencies by scrapping and merging some, the government has actually nearly trebled the number of the agencies in the 10 years since the Oronsaye Report, with little discernible improvements in the delivery of public goods.

Efforts have been made to reform the federal civil service, but those efforts have been constrained by wider issues of underinvestment, outdated processes and procedures and limited adoption of technology. Many of the issues bedevilling the civil service, including appointment, promotion, discipline and pay, are outside the control of the Head of the Civil Service of the Federation. There is still no link between government priorities and the job descriptions of individual civil servants, so people are not clear what they are coming to work to do on a Monday morning.

Without focusing on the external levers that affect the civil service, the effects of any civil service reform efforts will be limited. Some state governments have made efforts at governance and public service reforms, but most of these have been sporadic, inconsistent and often half-hearted. There has been a lot more appetite when monetary incentives are offered, as was the case in the hugely successful State Fiscal Transparency, Accountability and Sustainability (SFTAS) programme supported by the World Bank.

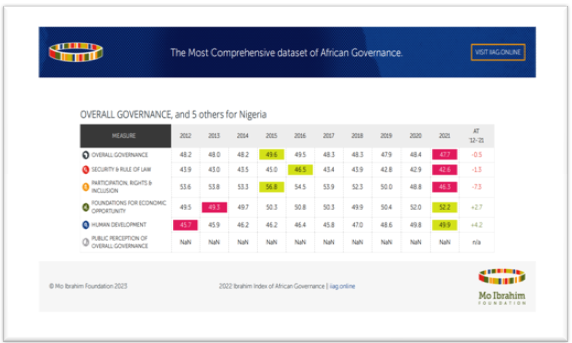

Independent measures of progress on governance reforms show that Nigeria’s performance has been subpar. For the 10 years from 2012 to 2021, Nigeria’s scores on overall governance on the Ibrahim Index of African Governance have consistently averaged 48%.7

Table 1: Nigeria’s performance on the Ibrahim Index of African Governance 2012-2021

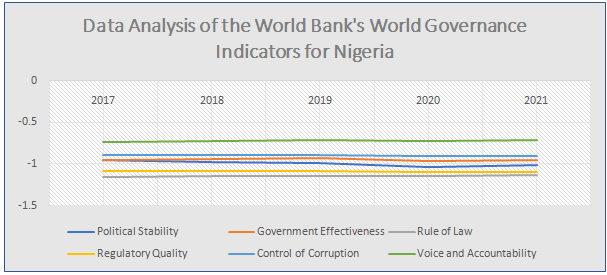

Performance against the Worldwide Governance Indicators for the period between 2017 and 2021 have similarly uninspiring.8

Figure 1: Nigeria’s performance on the Worldwide Governance Indicators 2017-2021

Options For Reinvigorating Governance Reforms

Governance reform is a very wide field, ranging from public policy, through human resource management, to public financial management (budgeting formulation, budget execution, accounting and reporting, debt management, procurement, and external scrutiny and audit), to implementation, execution, monitoring, evaluation and reporting. Consequently, it would be prudent to focus on only a few levers that could have a transformative effect on improving public governance and the delivery of public goods. In this memo, we choose to focus on seven levers: creating a sense of a movement; cutting waste and reducing the cost of governance; rebalancing the public service; raising productivity; improving performance management; connecting with the public; and improving the quality of policymaking.

A sense of a movement

Although several helpful reforms have taken place in Nigeria, what has been missing since 2007 is a sense of a reform movement: a feeling that Nigeria is serious about improving governance for its citizens and that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. This would require the new president to set the tone very early on in the administration that it will no longer be business as usual. The president must rise to the responsibility of reforms through the challenge of personal example, which Chinua Achebe described as the hallmark of true leadership. This would mean showing personal prudence, fiscal responsibility and attempting to gain first-hand knowledge of what citizens experience when they come into contact with their government. This can be done through unscheduled visits to public organisations and ‘mystery shopping’ which entails seeking the provision of public goods while pretending to be an ordinary citizen. The feeling of a movement towards reform will lift the whole ecosystem beyond just focusing on islands of effectiveness.

Reducing the cost of governance and cutting waste

It is important to revisit the Oronsaye Report. Although it is now more than a decade old, most of its recommendations remain valid but have never been implemented. Of all the organisations recommended for abolition or merger, only the National Poverty Eradication Programme (NAPEP) has ever been abolished. In its stead, a new Ministry of Humanitarian Affairs, Disaster Management and Social Development has been created. The impact of the ministry since its creation needs to be evaluated, and the mystery needs to be resolved about the beneficiaries of its interventions and the methodology and data on which their selection was based.

As mentioned earlier, the number of agencies in Nigeria has more than doubled since the Oronsaye Report. However, it is instructive to note that the Oronsaye Report not only proposed organisations that should be abolished or merged but it also listed several organisations that should have stopped receiving government funding for the last 10 years, because they generate revenue or have the capacity to do so. Additionally, the report highlighted some agencies and commissions whose governance arrangements should be streamlined for greater effectiveness. BusinessDay newspaper suggests that implementing the Oronsaye Report could save Nigeria N3.7 trillion!9

Admittedly, abolishing or merging agencies is a difficult task, especially as most of them are established by law, and the issue of potential job losses is always an emotive and politically difficult one. However, the government can implement the recommendations in stages, starting with those organisations that should no longer be getting appropriations from the federal budget. The difficulty of having to propose specific legislation to abolish or merge each individual agency can be addressed with a single Agencies Reform Bill that abolishes or merges the named agencies. That was what was done with the single Petroleum Industry Act that abolished the Department of Petroleum Resources, the Petroleum Products Pricing Regulatory Agency and the Petroleum Equalisation Fund.

(On a related note, there is also an urgent need to tackle oil theft and the vandalisation of oil pipelines. These are best done by deploying technology and visibly sanctioning wrong doers. There is also an urgent need to remove fuel subsidies. Projected to cost $16 billion in 2023, the projected subsidy payments are said to be double the expenditure of all the 36 states of the federation put together.10 Nigeria can simply not afford the level of expenditure to subsidise petrol for urban dweller and neighbouring countries (due to smuggling). Rural dwellers have been paying higher prices for years. The savings from removing petrol subsidies can be ploughed back into human capital development—including education and health—, investing in the civil and public service with better quality personnel and cutting-edge technology, and can also be invested in power and infrastructure development.)

Rebalancing the Public Service

A commonly- held view in Nigeria is that the public service is bloated, and needs to be drastically reduced. This view is not backed by evidence and is incorrect. According to the Federal Government, Nigeria has 720,000 public servants.11 This data was taken from the Integrated Payroll and Personal Information System (IPPIS), the computerised payment system through which public servants get paid their salaries. Some organisations like the Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS), the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and the group of entities that formerly made up the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) are not on IPPIS. Even allowing for those that are not on IPPIS and the usual practice by agencies and parastatals of engaging many casual staff and interns, the federal public service is not large by any measure. If we take the unlikely but worst-case scenario that the total numbers would be double what is on IPPIS, that would still be 1,440,000 people. Government employment in the United Kingdom central government wasat 3.6 million as of December 2022, while the total number of UK public servants was estimated to be 5.8 million.12The total number of public servants in Nigeria (federal, state and local government) is estimated at 2.2 million.13Based on 2016 data, Nigeria has one of the lowest general government expenditure in Africa, with general government final consumption accounting for only 5.9% of GDP, compared to other large countries like Ethiopia at 9.7% and Egypt at 11.4% of GDP.14

The issue with the Nigerian public service is that its personnel is poorly distributed, with too many people doing too little, and quite a few people doing too much. There is a need to rebalance the public service to ensure that people are deployed into areas of the greatest need.

The Nigerian public service needs more doctors and other health workers, police officers and teachers. Those public servants that loiter around government ministries and who create the impression that there are too many people with nothing to do should be repurposed to collect more taxes or deployed on the streets to inspect and monitor, in real time, the quality of public services being delivered to citizens.

Raising productivity

Although it is important to reduce the cost of governance and cut waste, there is a minimum level resources required to run a functional government. Therefore, the effort to reduce waste must be complemented by an effort to raise productivity and income. Nigeria must simply produce more. Efforts must be made to raise agricultural and manufacturing output and maximise revenue from solid minerals and the entertainment industry. Nigeria is one of the world leaders in terms of payment platform systems. Government must encourage this industry and the entire information communication and technology industry without getting in their way. It is also vitally important to focus on trade facilitation and to take full advantage of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) regime. The Federal Government recently ranked the Nigeria Customs Service as the least compliant in the ease of doing business regime. Unless the Customs Service is repurposed to focus on trade facilitation, rather than seizures and arrests, the benefits of AfCFTA will remain a distant mirage.

Managing and reporting performance

Performance Management is vitally important. In 2019, the Federal Government identified nine priority areas for the administration and put in place performance indicators and targets for ministries. It also set up a Central Delivery and Coordination Unit (CDCU) in the Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation to track performance against the targets. The results are presented and discussed in annual Presidential Ministerial retreats. This is a commendable practice and should be sustained. However, the citizens tend to experience government through agencies and parastatals than through ministries. There is no equivalent process of setting targets and monitoring them even if just for certain priority agencies and commissions. It would help if something like the existing performance management of ministries is put in place for priority agencies.

Connecting with the public

Government communication has been historically poor in Nigeria. The legacy of military rule in Nigeria still means that many government organisations do not feel the need to communicate and engage with the public. What communication exists is often defensive, combative and reactionary. This creates a credibility gap that means even when good work is being done, public perception is that it is not. As an example, data presented at the 2022 Presidential Ministerial Retreat showed that successful prosecution of corruption cases rose by 55% in 2022, and there was a 103% increase in the number of successful criminal prosecutions. But, on the other hand, citizen awareness dropped from 65% in 2020 to just 12% in 2022. It is little wonder then that public perception of anticorruption efforts continues to decline. Government’s mindset on communications needs to change. The image is as important as the substance and in today’s world of social media misinformation and

disinformation, your work alone no longer speaks for you. You must also speak for your work.

Improving the quality of policymaking

Probably as an enduring overhang of military rule, policies in Nigeria tend to be made with a measure of arrogance. The key ingredients of good policymaking such as the use of data and evidence, political economy analysis, cost-benefit analysis, risk-mitigation strategies and contingency planning, and comprehensive stakeholder consultation, are often ignored. A recent example of this poor approach to policymaking is the recent CBN cash confiscation fiasco. Conscious effort should be made to ensure that policies that are likely to affect the lives of citizens are thoughtfully developed and that key stakeholders are consulted before they are put in place. The rush to make announcements and think later must be reversed.

Recommendations

To pull the levers that will trigger an acceleration of governance and public service improvements in Nigeria, we make the following recommendations:

- The new president, in words and actions, should create a sense of a reform movement in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. He should lead this movement through personal example.

- There is an urgent need to reduce the cost of governance and cut waste. Initiatives here should include implementing the Oronsaye Report in phases and removing petrol subsidy.

- There is a need to rebalance the public service to ensure that personnel are deployed in the areas of greatest need and that future recruitment priorities essential workers like doctors and other health workers, police offices, teachers and quality-of-service inspectors.

- There is a need to raise productivity by facilitating an increase in agricultural and manufacturing output and promoting information and communication technology, particularly with payment systems where Nigeria competes favourably with the best in the world.

- There is a need for enhanced focus on Performance Management. Particularly, it would be necessary to set priority targets at the start of the administration. Ministers should also be issued Ministerial Mandate Letters where the president sets out his personal expectations of each minister upon their appointment. We also recommend that the current performance management system in place for tracking the performance of ministries is sustained and that a similar system for tracking the performance of agencies be put in place.

- Government should focus on strategic and agenda-building communication rather than on reluctant, reactive and defensive communication. Government should have people that are grounded in public policy and strategic communications engaging with the public, explaining government policies in a relatable way and channelling constructive feedback from citizens into improved delivery of public services. The usual practice of engaging journalists principally to defend the administration and attack perceived political foes is now outdated and ineffective.

- Government’s approach to policymaking should be more thoughtful, technically sound and consultative. Thoughtless and arrogant policymaking inflicts unnecessary hardship on citizens, damages the economy and erodes any goodwill the people may have for the government.

Conclusion

The Nigerian public service has continuously evolved since the return to democratic rule in 1999. From rule-based reforms in the first few years, there is now increasing focus on what the citizens experience when they come into contact with their government. Measured by most indices, public service performance has been weak in aggregate terms. One key reason for this is the lack of a sense of movement: a feeling that the public service is changing for the better and that it is no longer business as usual. If the new President can pull this reform lever, it would be a lot easier to pull the other six catalytic levers set out in this memo for accelerating governance and public service reforms in Nigeria as a whole.

*Dr Abah, the Country Director of DAI, was the Director General of the Bureau of Public Service Reforms (BPSR).

Footnotes

[1]https://mo.ibrahim.foundation/iiag

[4]https://nimc.gov.ng/enrolment-dashboard-march-2023/

[5]https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/nigeria

[7]https://mo.ibrahim.foundation/iiag

[8]https://databank.worldbank.org/source/worldwide-governance-indicators

[11]https://dailypost.ng/2022/06/23/ippis-720000-public-servants-working-at-federal-level-bpsr/#

[14]https://mo.ibrahim.foundation/sites/default/files/2021-06/2018-forum-report.pdf

Subcategories

Policy Insight

Policy Insight