By Adedayo Bakare | On his inauguration day on 29th May 2023, President Bola Tinubu declared Nigeria open for business.

The immediate priority of the then new government was the removal of petrol subsidies to repair government's finances, which had been damaged by a heavy debt burden.

The presidency also changed the leadership of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and initiated foreign exchange reforms that were introduced to correct the illiquidity and wide arbitrage in the currency markets.

These initiatives were well received by investors but the initial excitement around the policies was not sustained, neither did it translate to tangible gains, such as new investments, due to legacy issues around the currency. With depleted external reserves, overdue FX obligations and large fiscal deficits, potential investors are still reluctant to invest despite improving sentiment. Meanwhile, existing investors and businesses are reeling from the pressures of record-high inflation and a sustained depreciation of the Naira, which is destroying earnings and their balance sheet.

Sustained weakness in oil exports due to low oil production means dollar liquidity remains an ongoing problem. Without meaningful external reserves cover and lack of access to debt markets due to high interest rates and weak creditworthiness, Nigeria is left with only two other options: exporting more and attracting more foreign investment. While these are not options that can provide immediate relief, they provide a more sustainable foundation for the future.

This should be the priority for the government: to make the strongest case for why Nigeria is a better investment destination than elsewhere, and to make choices that will enable Nigeria to participate optimally in global oil and non-oil trade.

In this policy note, we will provide historical and contemporary context to the nature of trade and investment in Nigeria, from which we will assess the policies of President Tinubu and offer recommendations.

President Tinubu’s Trade Agenda is Still Unclear

After one year in office, there is not much to hold on to in terms of trade and investment policy other than the president’s campaign manifesto. In the manifesto, trade and industrial policy seem to be continuing in the all-too-familiar path of importing less and producing more for domestic consumption.

The Minister of Industry, Trade & Investment, Dr. Doris Uzoka-Anite, launched the Trade Policy of Nigeria (2023-2027) in December 2023. From all indications, the policy was prepared and approved by the last government. On paper, the Trade Policy of Nigeria (TPN) covers many necessary aspects needed to capitalise on trade for economic development, such as encouraging exports through incentives and liberalising imports to support manufacturers.

However, the TPN conflicts with the president’s manifesto in some ways. The policy document sees the need to liberalise imports but the manifesto is keen on reducing import dependency, encouraging more domestic manufacturing for local consumption, and to a lesser extent, exports. To promote import substitution, the manifesto puts forward tariffs, taxes, and processing fees on non-essential imports.

Another inconsistency is that the president’s manifesto treats exports as an afterthought unlike in the TPN. The TPN lists incentives to promote exports, such as export processing zones, tax incentives, export warehouses, among others. After one year, it is hard to tell the direction in which trade policy is leaning, whether in favour of the manifesto or the TPN, as tangible measures are yet to be taken.

Other notable trade measures circulating include the need for Nigeria to take advantage of preferential trade schemes providing access to advanced markets. An example is the European Union’s Generalised Scheme of Preferences (GSP) created in 1971, which eliminates import taxes on exports originating from developing countries. It is reported that Nigeria did not take advantage of this scheme until 2019 and only 100 companies have benefited so far. The US’ African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), expiring in 2025, is another one of such preferential trade agreements that are yet to be fully utilised.

The Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment and the Presidency are also exploring partnerships on talent exportation and trade and investment with the UK, India, UAE, among many other countries. What such partnerships would look like is unclear and no concrete agreement has been reached.

Gaps in the President’s Manifesto and the Trade Policy of Nigeria (TPN)

One big omission from both the president’s manifesto and the TPN is the failure to show the urgency of boosting exports in the face of rapidly falling domestic demand.

The export measures put forward by the TPN, such as export processing and free trade zones and tax incentives, are all existing initiatives. They were mentioned in passing, and no audit was done on why these incentives have not worked as expected in the past. The policy document was also silent on how best to take advantage of them to boost exports in the future.

While the TPN mentions the need for export diversification, it sets no direct target on exports, nor does it list sectors that would drive exports and the expected exports value. The policy document also ignores the oil sector, which currently accounts for over 90% of total exports and in which Nigeria has huge untapped resources.

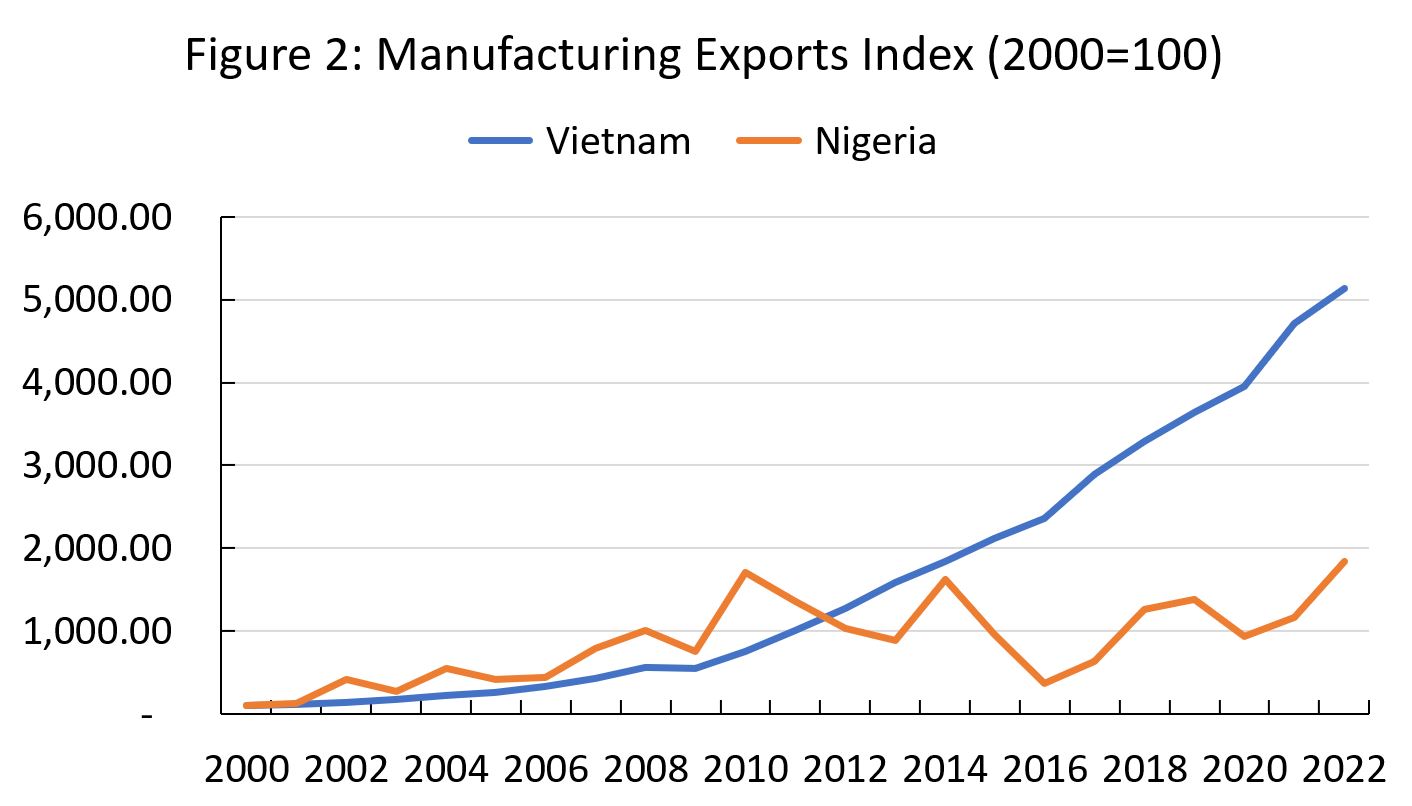

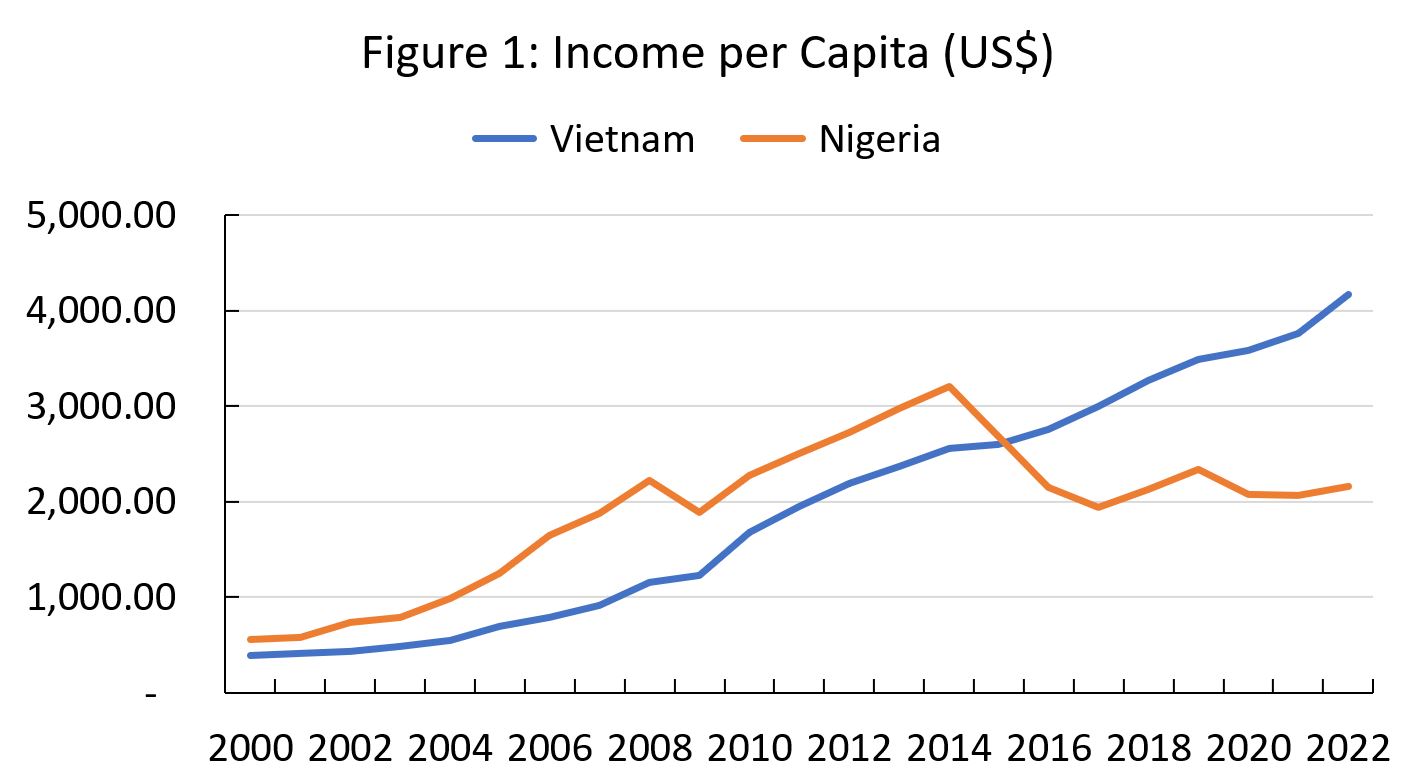

In the president’s manifesto, import substitution is still popular as an industrial strategy despite poor domestic demand. Yet, the experience of poor countries that have become rich, mostly in Asia, would suggest a different strategy. Most recently, Vietnam has increased per capita income at 12.5% annually from $359 in 2000 to $4,163 in 2022. It has done this by growing exports by 15.9% annually from $14bn in 2000 to $371bn in 2022. Exports growth has been diversified, reflecting a boom in both primary commodities and manufacturing exports. However, Vietnam has placed more reliance on labour-intensive manufacturing in the form of textiles and footwear, and capital-intensive manufacturing such as electronics, which are now 85% of the country’s total exports from 42% in 2000.

The idea, put forward in the president’s manifesto, that a country can export more and import less is also not consistent with any industrialisation-driven growth strategy. In the Vietnam case, for instance, the importation of parts grew at roughly the same pace as exports. To increase the exports of electronics from $768m to $133bn, imports of electronic parts and components had to grow from $903m to $100bn. It is impossible to produce, whether for local consumption or exports, without imports.

In essence, import curbs would be devastating for local production, while it is likely to make exports uncompetitive as exporters must seek to be competitive across their entire value chain. There is hardly any industry in Nigeria today with a competitive value chain domestically that can compensate for imports.

Source: UNCTAD, Author’s Computation

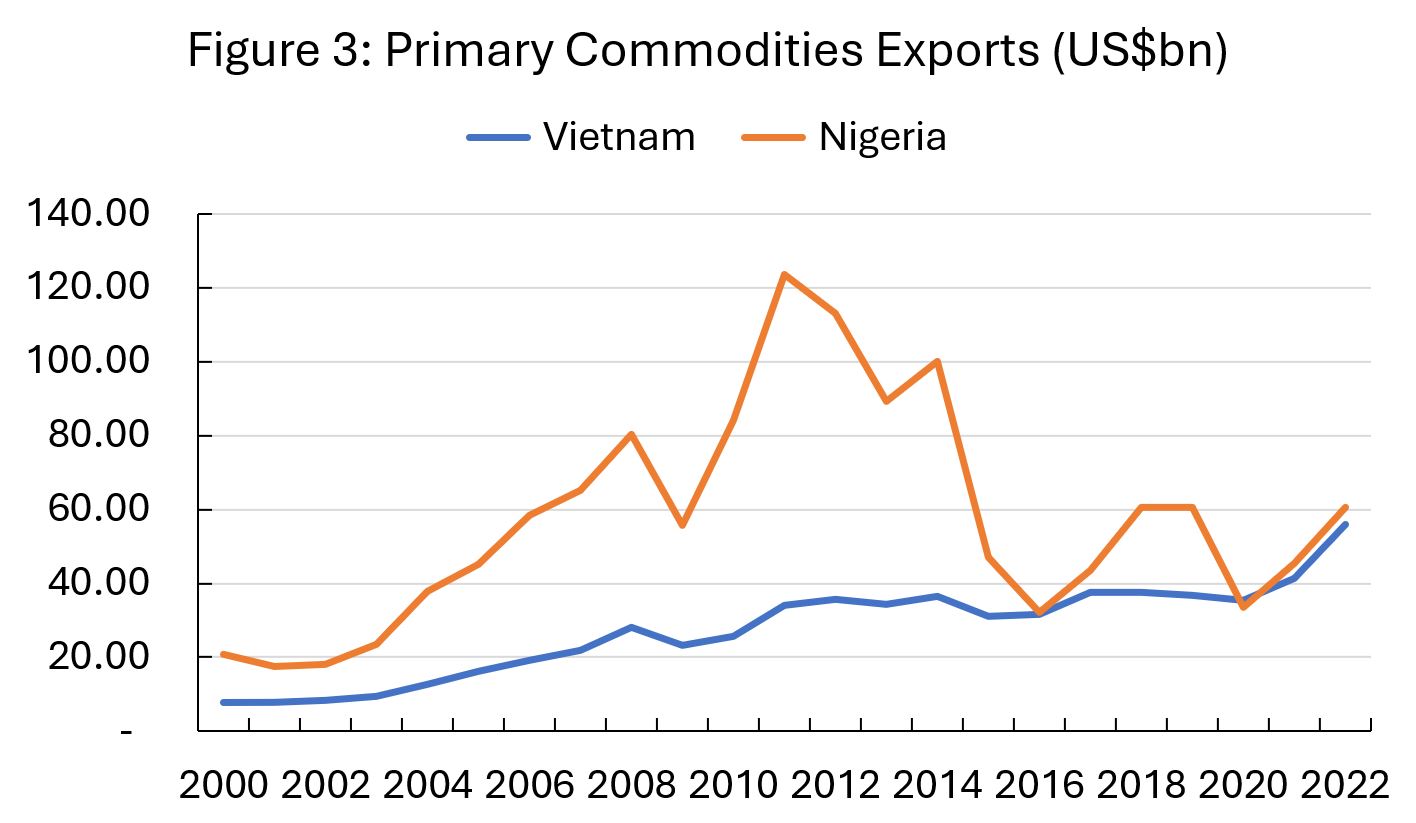

Source: UNCTAD

Import restrictions can also be arbitrary. The government is yet to decide on what is essential and non-essential trade. Tragically, if history is any guide, going by the definition of the CBN under Godwin Emefiele, which banned FX for the importation of 43 non-essential items, these tend to be primary commodities that are required for further processing. Such restrictions would be crippling for local manufacturers.

It is noteworthy that, in practice, the CBN has relaxed restrictions on these 43 items, for which importers can now access FX in the official markets. However, high tariffs remain an even bigger cost that is unlikely to be relaxed. It could be argued that CBN’s decisions were meant to promote efficient pricing in currency markets, and not necessarily as a means to support trade and manufacturing.

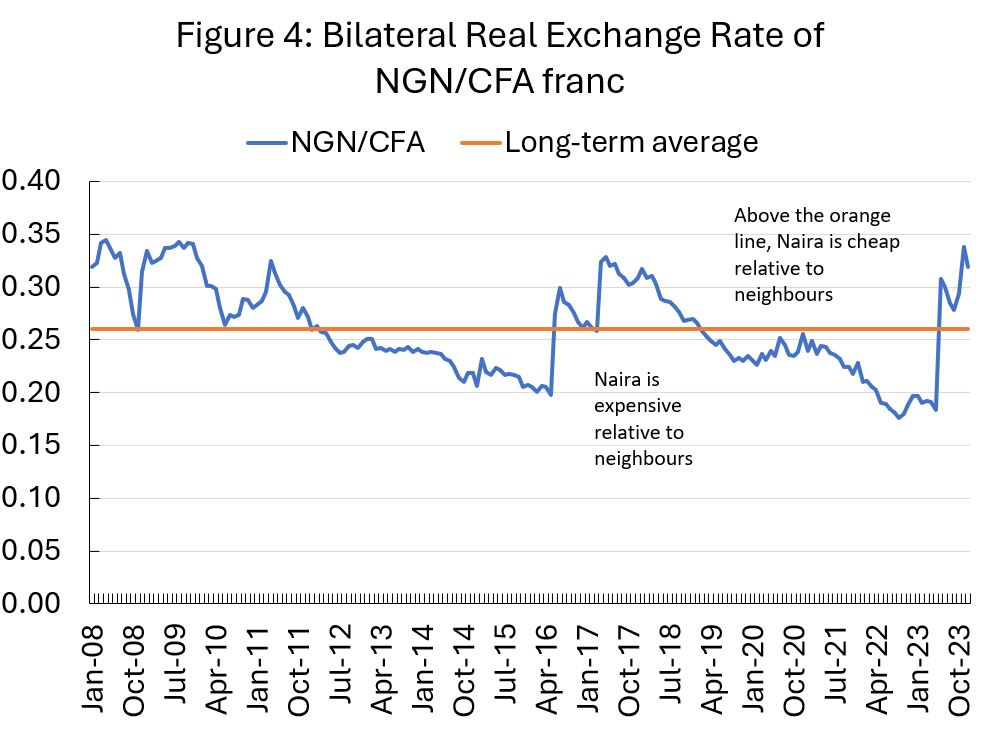

The biggest boost to non-oil exports has not been any deliberate policy targeting it, but the rapid devaluation in the Naira that has boosted competitiveness relative to our West African neighbours. Using Côte D’Ivoire as a proxy, Naira’s real exchange rate, a much better measure of competitiveness than nominal exchange rates, depreciated by 42% between May and December 2023 compared to a 78% appreciation from May 2017 to May 2023. However, this comes with unease given the high and rising food inflation rate, which was at 40.5% in April 2024.

Source: CBN

To bring down inflation, the government has been actively discouraging food exports, and is considering shutting the borders. Lessons from history as recent as 2019/20 when all land borders were shut indicate that this is unlikely to work. Such a drastic measure would only push more exporters underground, giving the government little visibility about their earnings. Many others will miss out on earnings that can enable them to invest to produce and employ more people. More importantly, it shows that the thinking around trade has not evolved to see opportunities instead of losses.

Nigeria is also yet to realise and position to take advantage of the competitiveness provided by a weak currency relative to its neighbours which rely on a stronger, pegged currency. Both the president’s manifesto and the TPN still prioritise a strong currency.

FX Reforms Doing the Heavy Lifting on Investment

The investment policy of President Tinubu so far has largely centred on FX reforms. The plan was to create an environment where investors can enter and exit with their earnings without hassles. The FX reforms over the past year, which include settling backlogs and the removal of arbitrage in the currency markets through market-driven pricing, have improved investor confidence.

Investors who have earnings to repatriate can now do that through the official market unlike in the period between 2020 and 2023 when there was thin liquidity in the official market. While this is exclusively a monetary policy action, the intervention of the presidency is evident.

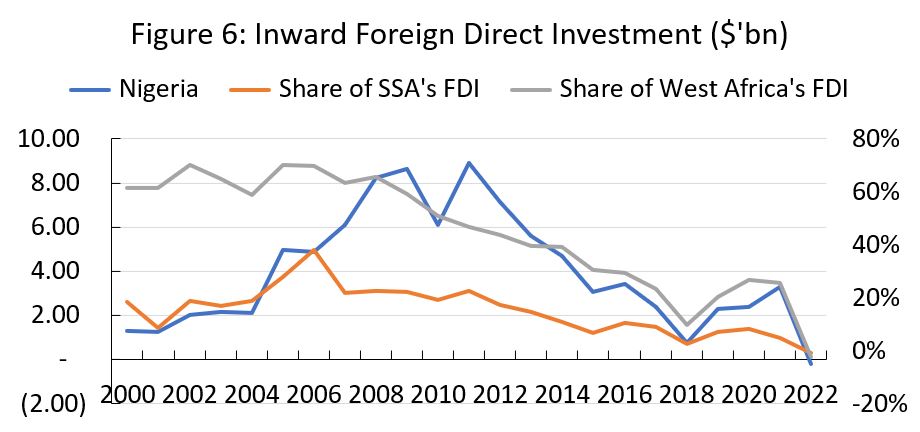

Ironically, the missing piece in terms of investment has been on the fiscal side. While sound monetary policy can attract short-term money flows into debt and equity securities, it is inadequate for long-term investment. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) takes the form of capital and expertise invested directly into businesses. Attracting FDI is only enabled by a good regulatory environment and reforms that create new opportunities. In highly-regulated industries like the oil sector, this has been Nigeria’s undoing in the last decade.

The current government has moved too slowly or not at all in this direction. There is evidence that the government recognises the need for trade and investment to recover from the current economic crisis. The government has been on the road, from UAE to Germany, seeking investment and trade partnerships. It is safe to assume that the purpose of these trips is to attract funding and source new markets. However, there is no coherent economic strategy backing these adventures.

What the government seeks to achieve and how it intends to go about it is unclear. What is Nigeria looking to sell to the rest of the world? What is Nigeria looking for investment to finance? Where are the opportunities being created to exchange value with other countries? These questions are unanswered. While still early days, the investment and trade partnerships being explored have not shown promise.

Meanwhile, the Ministry of Industry, Trade and Investment announced a sector agnostic 10-year $10bn Diaspora Fund which will enable Nigerians in the diaspora to finance development at home. The Fund is currently seeking investment managers who will deploy the capital raised to generate returns in the economy. This is a good move given lack of access to debt markets for cheap financing and low FDI. However, there are concerns about the suitability of retail investors to finance long-term investments and the return expectation given the huge underperformance of the economy on a dollar-adjusted basis over the past decade. These issues lower the chance that the total fund size will be raised in the short-term.

For any chance at restoring stability and putting Nigeria on the path of resilience, the Tinubu government must redefine its trade and investment agenda.

Disrupting the Outsized Share of the Oil Sector in Trade and Investment

At the centre of Nigeria’s current economic crisis lies a decade-long inability to boost and diversify exports, and attract foreign investment to fund its ambitions.

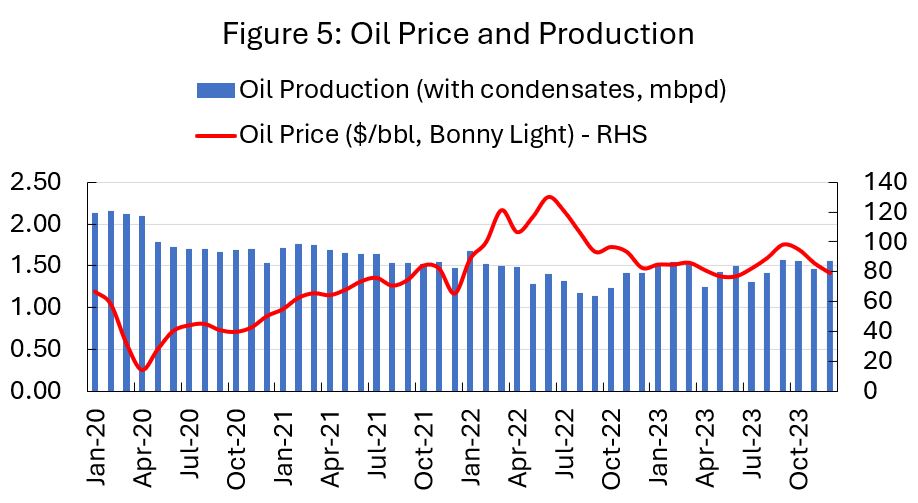

An oil-induced crisis is not new, as it happened in the 1980s, 1990s, and mid-2010s. However, this time is different. While previous episodes of falling exports, as well as the attendant FX supply issues, could be attributed to a sharp contraction in oil prices, this is not the case recently. Since 2020 oil prices have averaged $83/barrel, in line with the historical average of $80/barrel.

The tragedy of dollar scarcity when oil prices are high is a domestic problem. Production in the oil sector, which accounts for more than 90% of total exports, has collapsed to the lowest in more than two decades. In Q1 2024, Nigeria produced less oil than it did in the 1970s. With one of the highest costs of production in the world, this effectively means that Nigeria is not deriving much value from its oil sector as before.

Source: CBN

The slowdown in oil production has been attributed to insecurity, which has led to alarming levels of oil theft. The untold side of the story is also that investment in the oil sector had come to a halt due to the uncertain regulatory environment. For instance, the flagship reform in the oil sector, reflected in the Petroleum Industry Bill, did not pass for 20 years. Neither did it excite investors when it was eventually signed into law. It is tragic that what should be a transformative reform for the oil sector has not yielded much gains. Investors have no reason to wait for Nigeria to get its act right.

In that span, other oil producers with a better regulatory regime and without domestic security issues attracted investment, despite the transition to renewable energy. Today, Nigeria faces an impossible battle in convincing oil and gas investors, both existing and new ones, to invest.

In the 1990s and 2000s, the oil sector was the main driver of growth, supporting other sectors to thrive through exports and FDI. According to CBN data, the oil and gas sector attracted over 50% of the FDI into Nigeria in the 2010s. At the peak, the oil sector accounted for more than 90% of FDI into Nigeria. It was so significant that Nigeria accounted for around 30% and 70% of the total FDI into Sub-Saharan Africa and West Africa respectively. Large exports and FDI supported consumer spending, which attracted more non-oil sector investment, and provided the FX required for Nigerian businesses to invest. The growth in the telecommunications and manufacturing sectors, which also attracted significant FDI, was in a large part fuelled by the oil success story.

The Vietnam experience shows that FDI in manufacturing can also be critical as it allows an economy to import capital and expertise needed for export operations. In the 2000s, FDI in manufacturing accounted for over 60% of exports in Vietnam.

Source: UNCTAD

Without reforms in the oil and non-oil sector and a stable macroeconomic climate in Nigeria, investors are exiting rather than expanding. The tight link between the oil sector and FDI in Nigeria has long been broken. There is an urgency for the government to re-establish this link while also prioritising export and investment in other sectors.

Trade and Investment in the New World Order

The world is becoming more insular. Four consequential events are reshaping the global order in this decade, and all four point to the need for domestic resilience. At the start of the new decade, the COVID-19 pandemic was a turning point in matters of global trade. As economies prioritised the home-front with policies that restricted trade due to uncertainties around the pandemic, vulnerable trading partners sought to localise more of their value chains to improve resilience.

The Russia-Ukraine War is another material event showing why economies must seek resilience. The synchronised and devastating economic sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine, while not unexpected, confirmed earlier presumptions. It has become clearer that going against some powerful economies have consequences. The biggest economies, especially those who are not allies to the West, and many of whom are embroiled in geopolitical conflicts, have paid attention. China and Russia, which are the primary examples, are unplugging from the existing global transaction order centred around the US financial system.

The continued dominance of China’s exports relative to the rest of the world is another source of unease. Since the collapse of China’s property sector due to bad loans, the Chinese are relying on exports to support growth. A sustained growth in Chinese exports will create problems for other countries which must run trade deficits, hence countries are starting to fight back through subsidies and tariffs. Even if not for the purpose of improving resilience, it is necessary to correct the misalignment of global trade and support domestic industries.

Then, finally, there is a rush for new technologies that could unleash a new era of productivity upon the world. We have seen this competition in the chips industry, which is a critical input for modern technologies. Many developed countries are financing this industry in the hopes that the capacity needed by the broader technology industry can be found at home, so as not to be beholden to trade partners. This also intersects with concerns about climate change, the need to transition from fossil to cleaner fuels, which cannot be done without better battery storage capabilities. China and the US are at the forefront of these battles.

In this new global order, developing countries like Nigeria without an existing exports-focused industrial base are at risk of further underdevelopment. As China continues to grow exports aggressively, these countries will not be able to compete. And, if the US and China, which are the biggest exporters of capital, decide to focus more on investing at home then some of these developing countries will be starved of foreign capital needed to support their economies.

Winning in the New Arena

Nigeria desperately needs economic prosperity that will lift poor people out of poverty by increasing earnings and employment for households. Similar to the 2000s when commodity exports drove per capita income from $563 in 2000 to $3,200 in 2014, Nigeria still needs external markets to buy what we sell. Nigeria as a consumer market has become much poorer over the past ten years, so this must be the overarching goal behind any trade and investment agenda.

More importantly, Nigeria must decide on what it wants to sell to the rest of the world and the sectors to prioritise for investment. This will require reforms in some cases, like in the energy sector. In other cases, soft things like making it easy to do business and export, and reforming the tax system and land ownership, will play a role. For instance, forcing exporters to convert earnings at an overvalued exchange rate will not incentivise more exports. The current situation is so dire that the structures supporting oil and non-oil trade are inefficient. This was not a big problem in the oil sector until recently.

Policymakers must abandon old ideas around trade and investment. Implementing high tariffs cannot create a sustainable or competitive local industry as we have seen in cement and automobile. Nigeria must confront the fact that both import-substitution and export-led growth strategies require importing from the rest of the world. We need to take advantage of efficiencies in the global value chain to compete with the rest of the world. If that holds true, then exporting more and relaxing import restrictions must be part of Nigeria’s industrial strategy.

Export restrictions, as we have seen of late, must also be relaxed. Competitive advantages created by the exchange rate depreciation must not be ignored but nurtured. This means the CBN must equally prioritise policies that will enable Nigerian businesses to compete better in global trade.

Indeed, investment-led growth strategies, which we have recently seen in many African countries such as Nigeria, Egypt and Ethiopia, also have constraints. Investment in infrastructure funded by foreign currency debt, which produces no export earnings, is largely responsible for much of the continent’s current currency crisis.

This supports the need to align foreign investment, either from equity or debt, to earnings that will pay for the returns. The foreign investors in the non-oil sector who do not export earn returns that must eventually be settled with dollars. It is no surprise that some of the recent challenges foreign investors have faced is that their earnings in the local currency could not be repatriated in dollars. This is a less severe problem in the oil sector, for instance.

Finally, we need to pay attention to the changing global order. The need for global superpowers to compete fairly on trade must be a critical component of Nigeria’s foreign policy and broader engagement. Establishing and extending fair trade routes in exports for developing economies in advanced markets is critical to creating more prosperity.

Ultimately, success will be determined by Nigeria’s capacity to take advantage of existing and new opportunities. To play in the new arena, we need forward-looking policies and reforms that have the potential to create mass prosperity.

*Adedayo Bakare is an economist interested in the growth stories of emerging markets.