By Ayobami Ayorinde, Uchechukwu Eze, Oluchi Nkeonye, and Seyi Akinbodewa | On 24th September 2024, the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) released two reports on the state of the labour force in Nigeria.

The reports, titled the Nigeria Labour Force Survey and produced in partnership with the World Bank and the International Labour Organisation (ILO), covered the whole of 2023 and the first quarter of 2024. The increase in unemployment from 5% in the third quarter of 2023 to 5.3% in the first quarter of 2024 has dominated the headlines.

Given what they know and see, many Nigerians are still struggling to wrap their heads around single digit unemployment rate, which resulted from a change, late last year, in how NBS calculates unemployment and does not diminish the fact that Nigeria still has a major challenge with putting its people to work. The two reports by NBS offer comprehensive and valuable insights into the dynamics and trends of the labour market in the country. In this post, we highlight some key insights and their implication for policy.

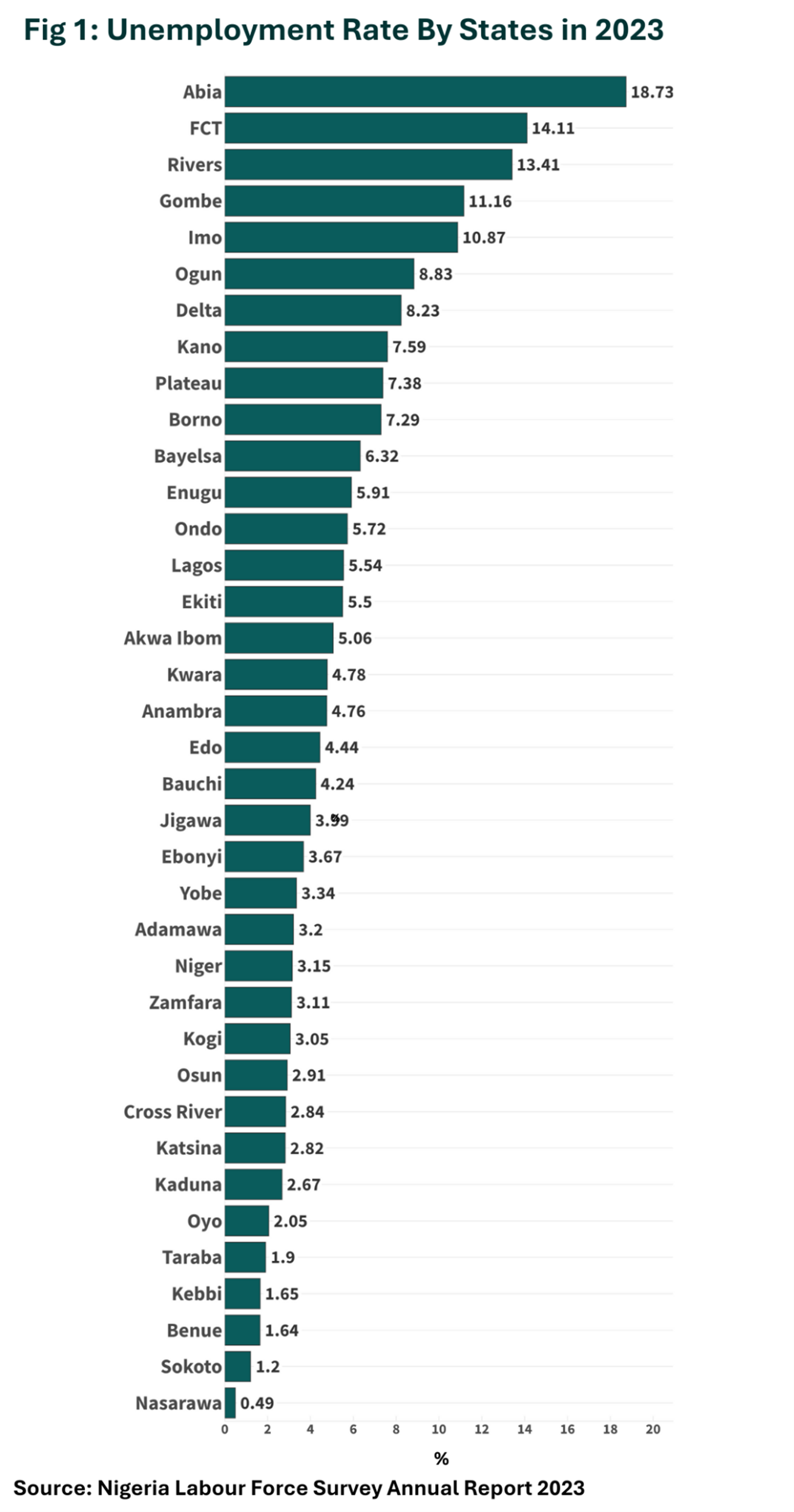

Insight 1: Abia State and South East Record Highest Unemployment Rates

From the report, Abia State had the level of highest unemployment, at 18.7%, which is significantly higher than the national unemployment rate of 5.4% in 2023. This places it ahead of the Federal Capital Territory (14.1%) and Rivers State (13.4%), both of which also face considerable labour market challenges. In contrast, Northern states like Nasarawa and Sokoto recorded the lowest unemployment rates at 0.5% and 1.2% respectively.

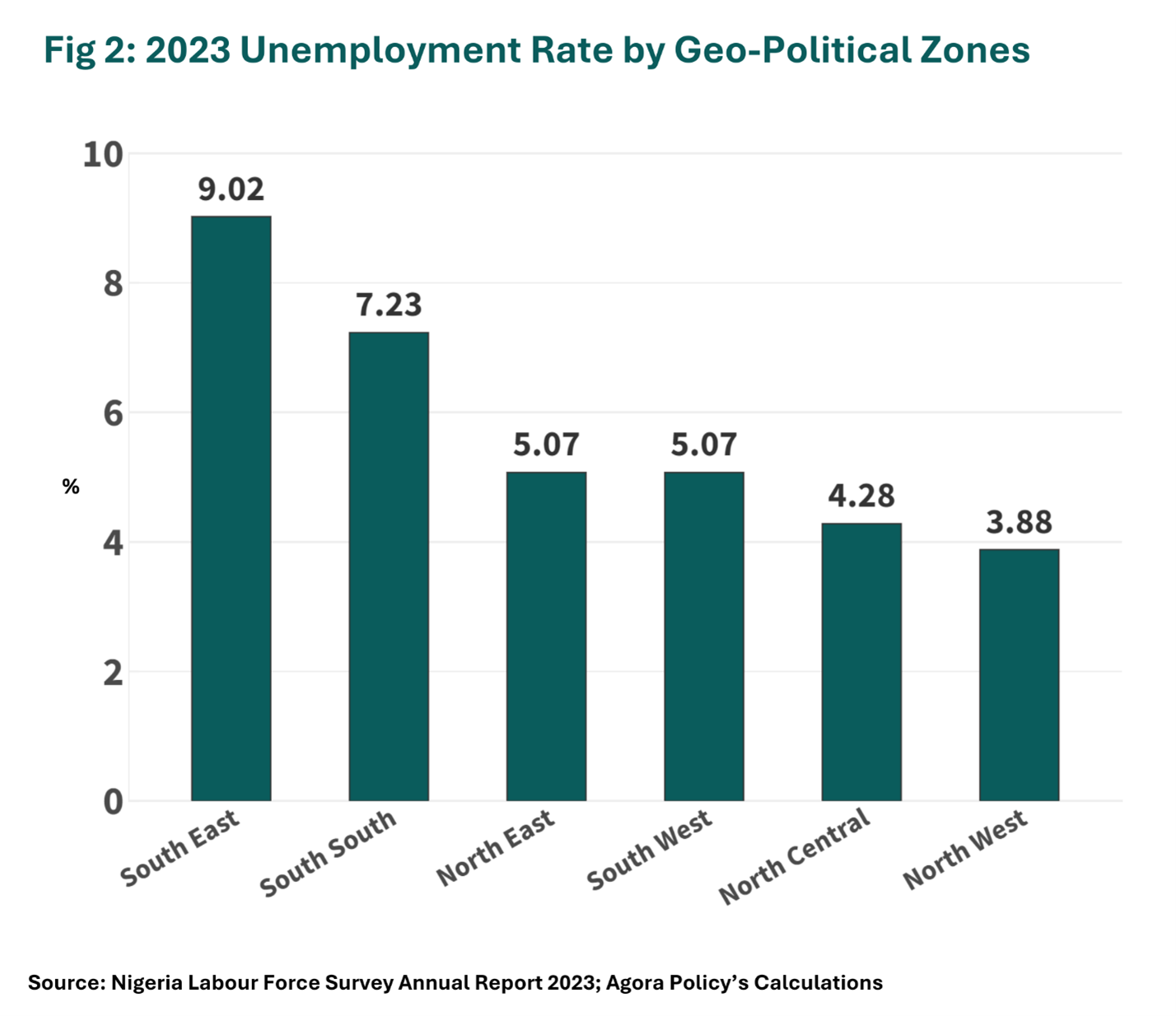

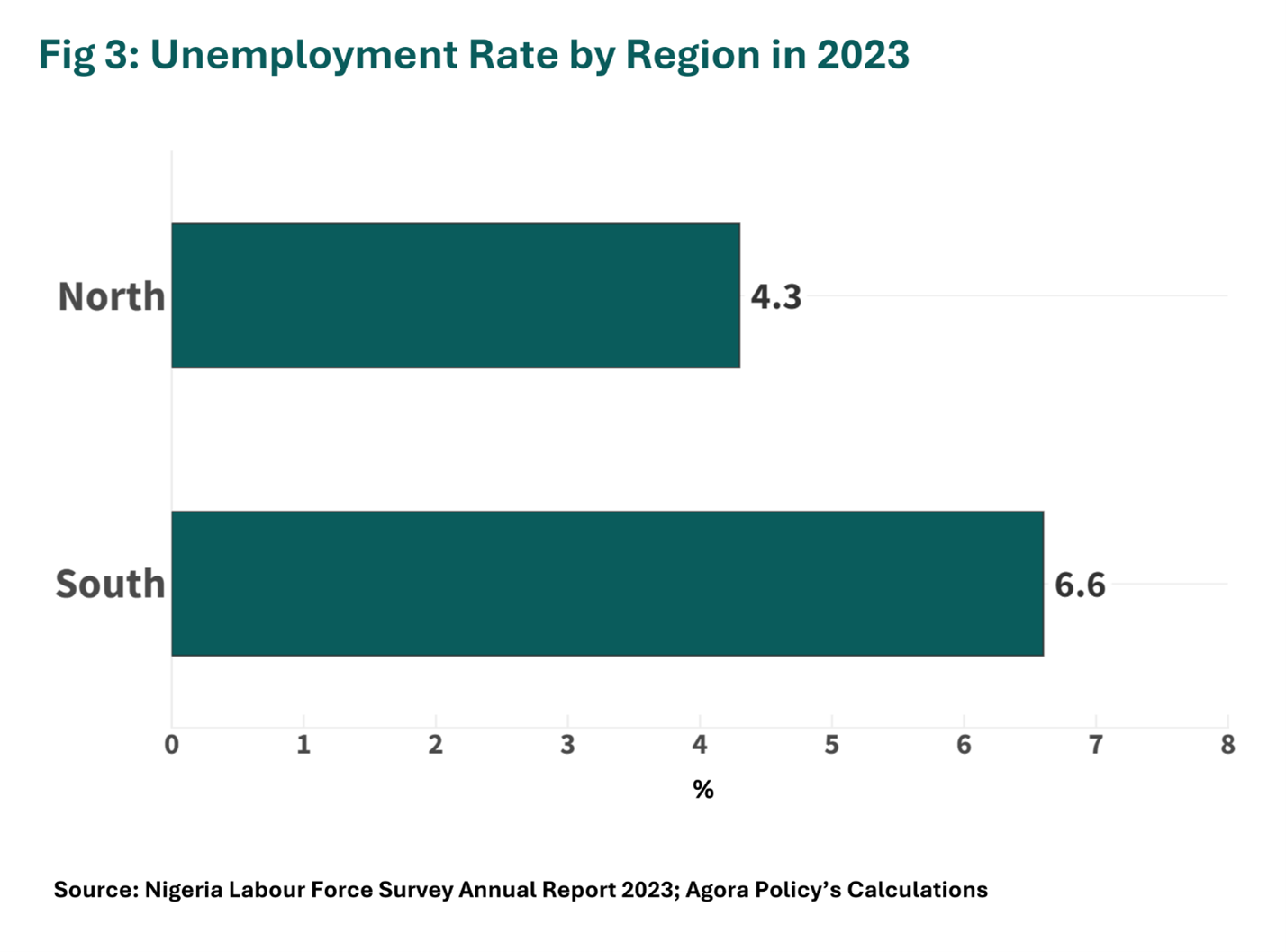

In terms of geo-political zones, the South East had the highest unemployment rate at 9.03%, while the South South followed at 7.24%, and the South West at 5.07%. The Northern zones fared better, with the North East and North Central regions at 5.07% and 4.28%, respectively, while the North West recorded the lowest rate at 3.88%. Overall, unemployment (as shown by our calculation) was lower in the North at 4.3% compared to the South which stood at 6.6%.

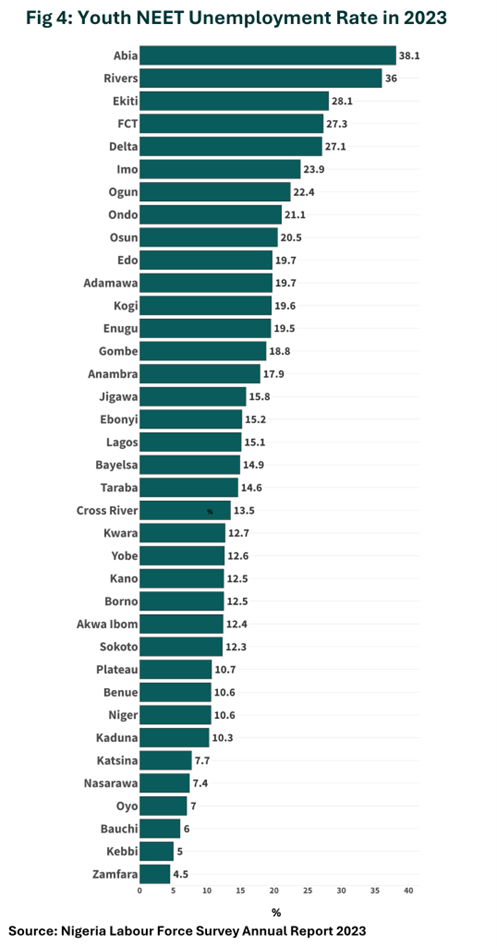

Another highlight in the survey report is the Youth NEET (Not in Employment, Education, or Training) rate, which measures the percentage of young people disengaged from the workforce and education system. Nationally, the NEET rate was 15.6%, with Abia and Rivers recording the highest rates at 38.1% and 36%, respectively. On the other hand, Zamfara had the lowest NEET rate at 4.5%, indicating stronger youth engagement in education, employment and training. This suggests that regions with higher unemployment rates also tend to have more youth disconnected from both work and educational opportunities. Addressing these gaps requires a focus on policies that re-engage young people and expand economic opportunities, particularly in the southern part of the country.

Another highlight in the survey report is the Youth NEET (Not in Employment, Education, or Training) rate, which measures the percentage of young people disengaged from the workforce and education system. Nationally, the NEET rate was 15.6%, with Abia and Rivers recording the highest rates at 38.1% and 36%, respectively. On the other hand, Zamfara had the lowest NEET rate at 4.5%, indicating stronger youth engagement in education, employment and training. This suggests that regions with higher unemployment rates also tend to have more youth disconnected from both work and educational opportunities. Addressing these gaps requires a focus on policies that re-engage young people and expand economic opportunities, particularly in the southern part of the country.

Insight 2: Higher Unemployment Observed Among Youths, Post-Secondary School Graduates and Urban Dwellers

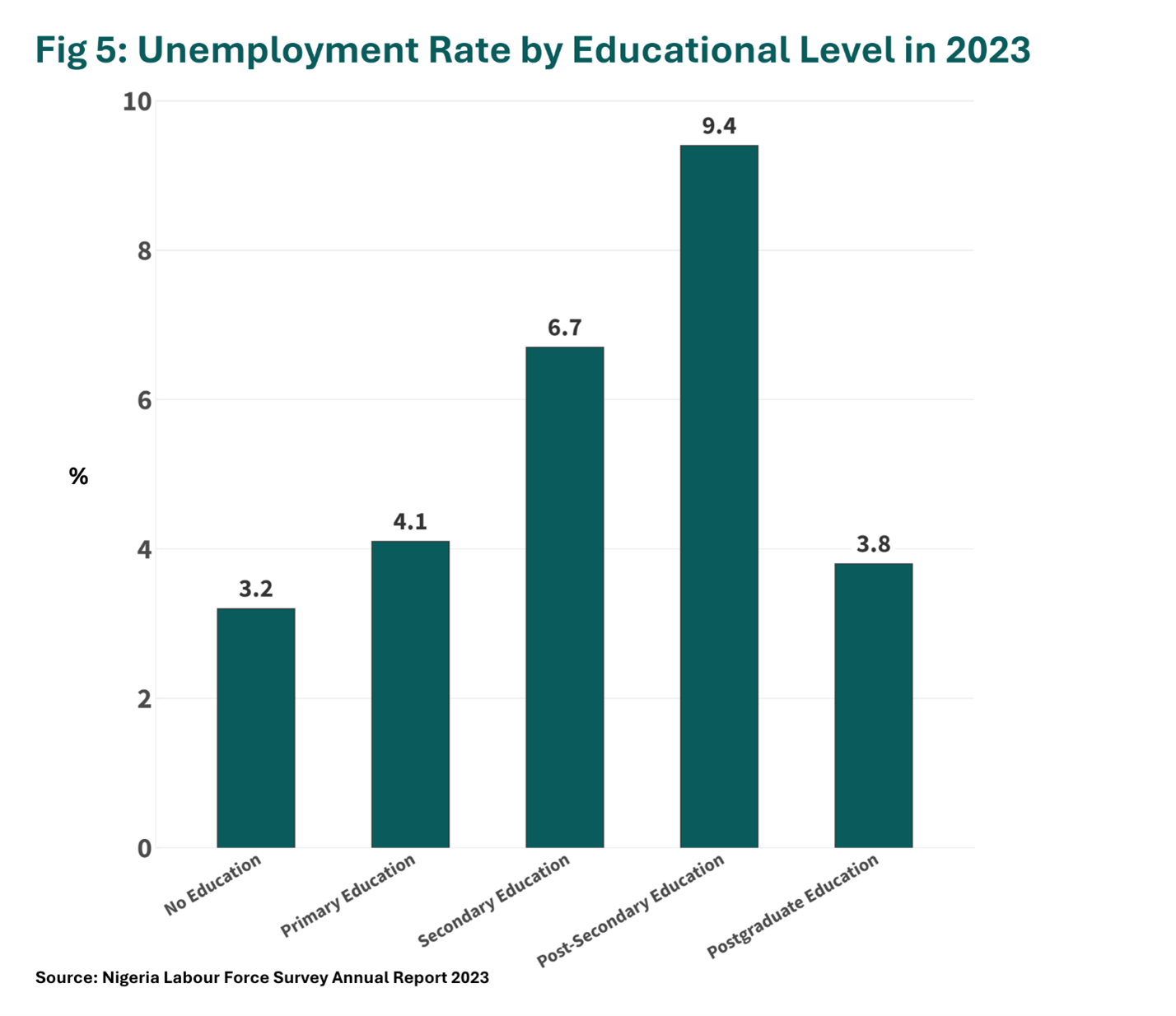

The report shows that Nigerians with no education have the least unemployment rate (3.2%) followed by those with post graduate education (3.8%), while those with post-secondary education have the highest unemployment rate (9.4%). This is likely because people with no education can accept low-skill jobs which are more readily available in a bid to fend for themselves despite the low wages it comes with, while those with post-secondary education often have higher job expectations in terms of salary, job roles, and career progression, and are selective about the kind of jobs to accept. As such, many young graduates may prefer to stay unemployed rather than work in low-skill or low-paying jobs.

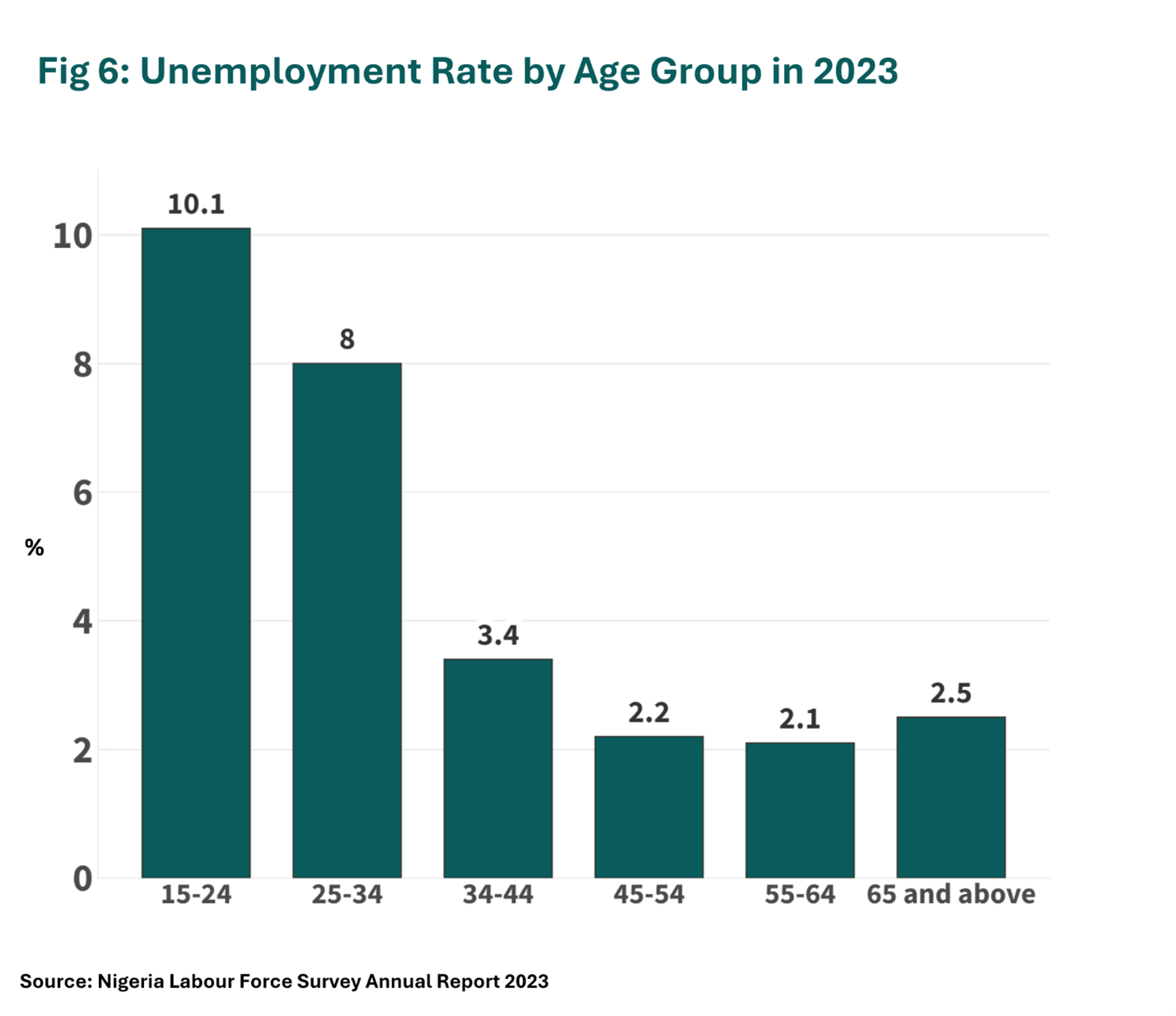

In addition, persons between the ages of 15-24 and 25-34 have an unemployment rate of 10% and 8% respectively whereas those who are 35 and above have an unemployment rate of less than 4%. This underscores the various factors that may be at play for young persons in the employment field. People in this group are usually either in school, completing a degree, or looking for their first job. As such, the transition from education to employment can be a contributing factor to higher unemployment in this age group. In addition, younger individuals are more likely to be competing for entry-level jobs, where the number of applicants far exceeds the number of available positions. This creates intense competition and higher unemployment among younger workers compared to those in their mid-career who may have more established networks, career progression and skills, thereby reducing the level of competition they face for jobs.

Furthermore, persons in the urban area have a higher unemployment rate of 6.8% compared to those in the rural area at 3.5%. This is because a larger proportion of people in rural areas are engaged in agriculture (69%) and food service activities (55%) which provides constant work for them thus lowering the rural unemployment rate.

Insight 3: Informal Employment Remains Prevalent in Nigeria

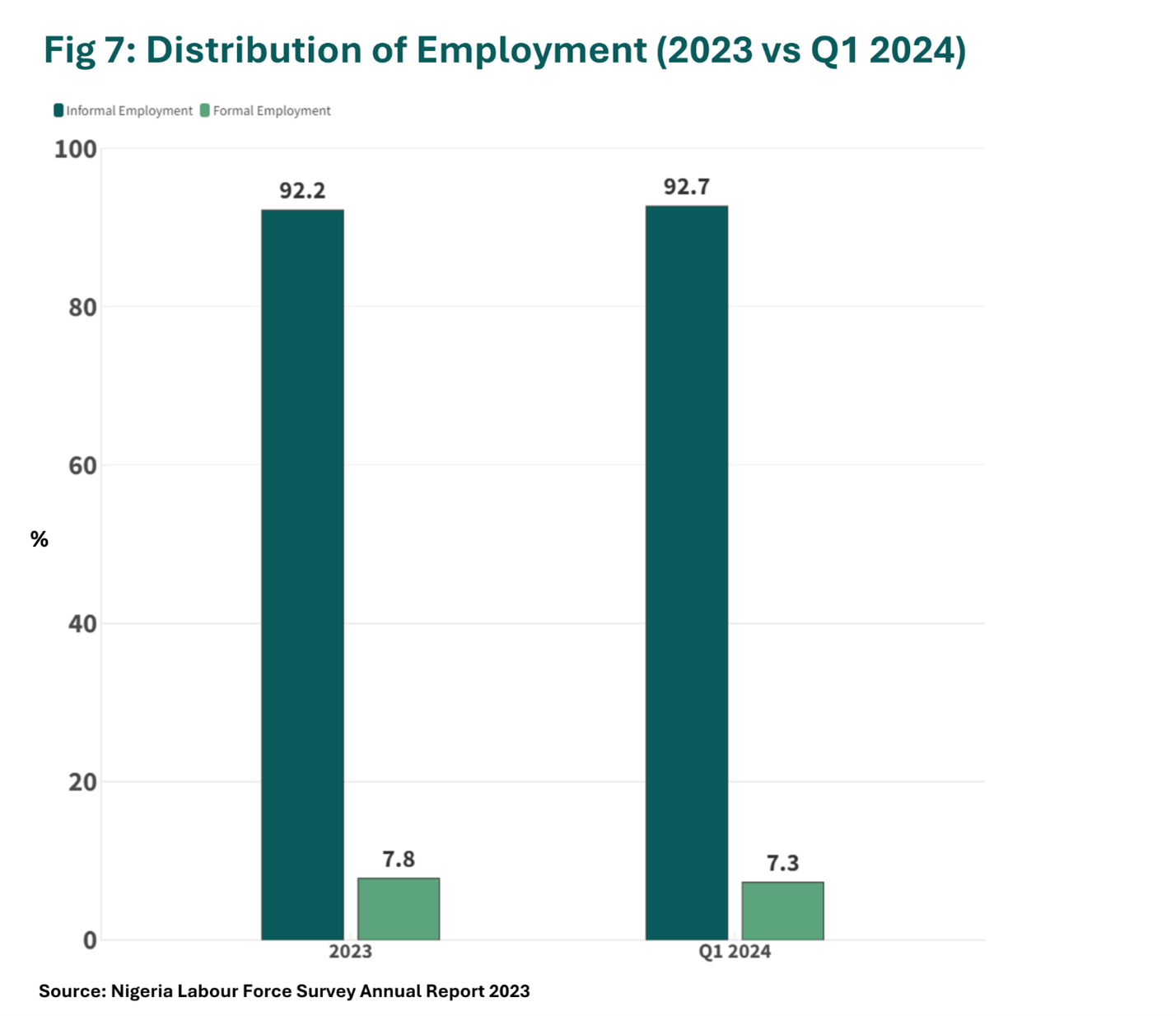

The informal sector continues to dominate Nigeria's labour market, representing a significant 92.2% of the employed population in 2023. By the first quarter of 2024, this figure had slightly risen to 92.7%.

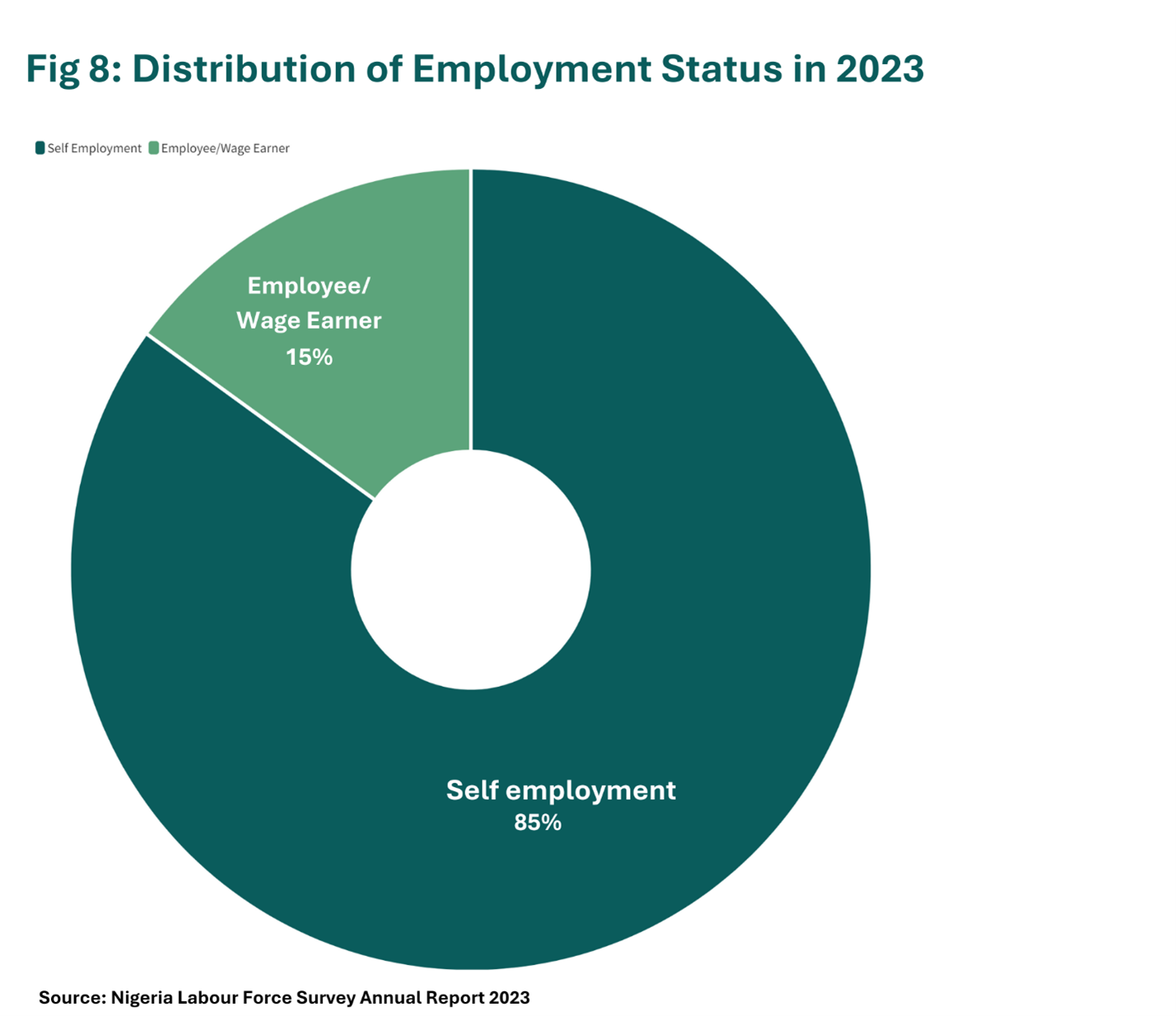

In addition, self-employment constitutes 85% of employed persons with wage earners constituting the remaining 15%. According to the report, informal employment refers to jobs that lack the essential legal and social protections typically associated with formal employment, such as health benefits, pensions, and contract agreements.

Many small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and informal sector workers avoid formal registration due to cumbersome regulations and the fear of being taxed heavily, and this widespread informal employment has several effects on Nigeria's economy and its workforce. From an economic standpoint for example, the lack of formal documentation of these jobs makes it challenging for the government to create effective labour policies and collect taxes. In addition, workers in informal jobs are more vulnerable to exploitation and job insecurity, as they do not have legal recourse if they are unfairly treated or dismissed. The high prevalence of informal employment in Nigeria shows the need for labour market reforms that can enhance worker protections and provide social security nets for employed persons. These reforms would further help improve Nigeria’s tax collection and allow more employees to be beneficiaries of labour policies like the new minimum wage.

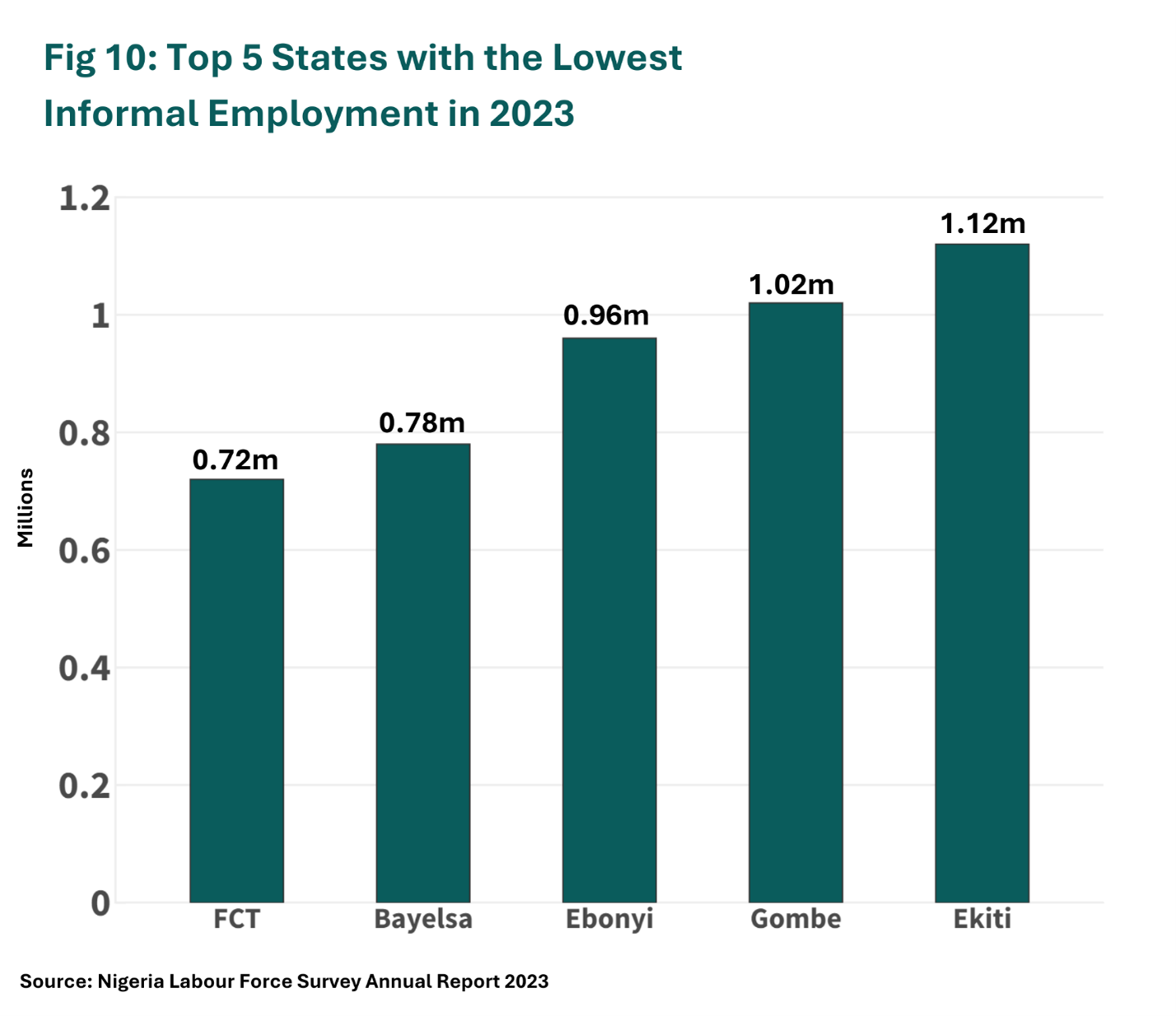

The states with the largest informal labour populations were Kano and Lagos, with 5.1 million and 4.6 million informal workers respectively. In contrast, the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) and Bayelsa recorded the fewest, at 721,365 and 783,274 respectively.

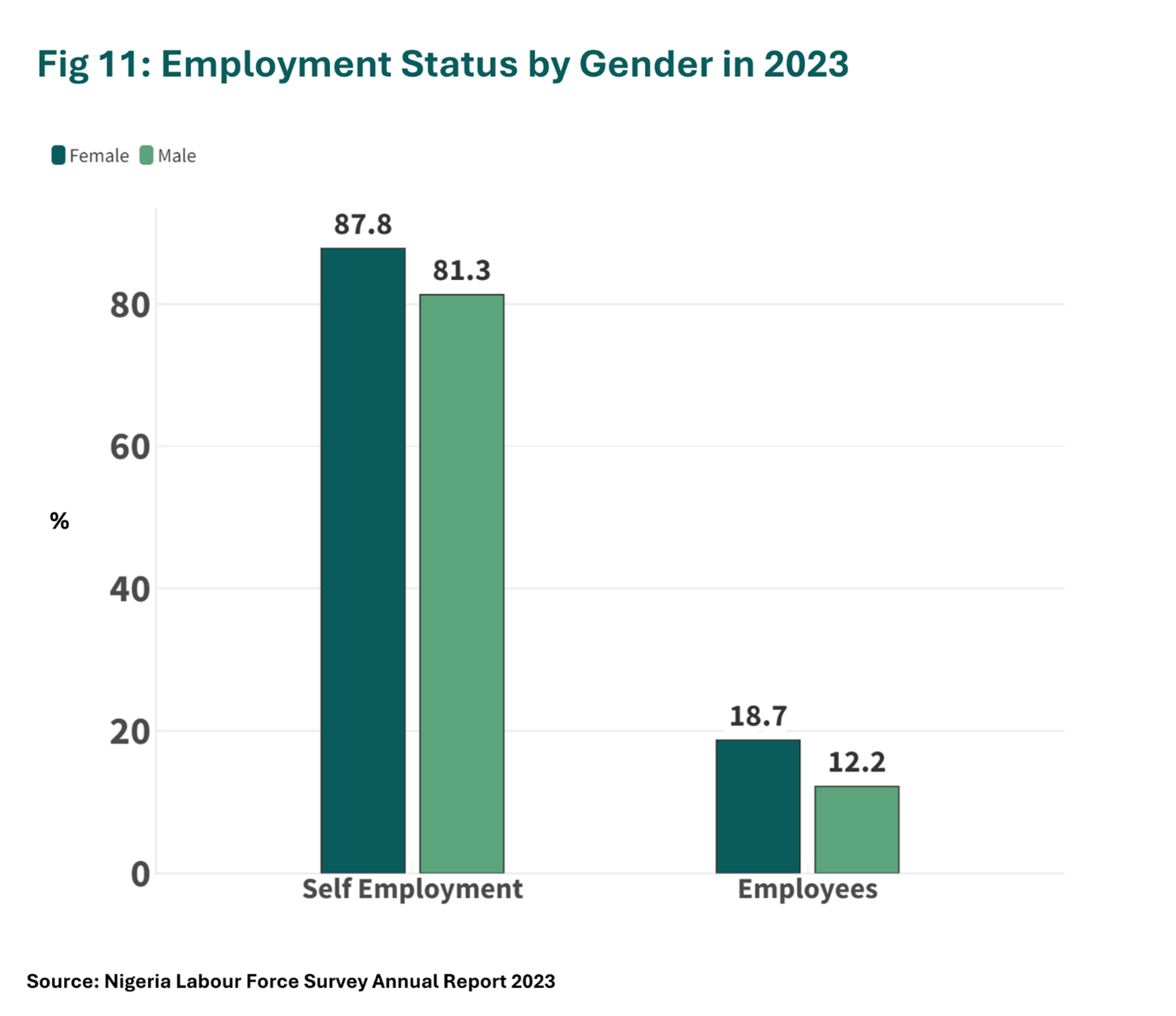

Insight 4: Gender Disparities in Nigeria's Labor Force: Women Dominate Self-Employment, Men Hold Formal Jobs

Nigeria’s labour force landscape highlights a significant gender disparity in both employment and labour force participation. In the working-age population, Nigeria has more females (52%) than males (48%). However, females have 6% unemployment rate compared to 4.7% for males. A striking contrast emerges in the nature of employment—87.8% of women are engaged in self-employment compared to 81.3% of men, indicating that women may face barriers to formal employment and often turn to entrepreneurship or informal work. On the other hand, men dominate the employee sector, with 18.7% employed compared to 12.2% of women.

This gender disparity in Nigeria's labour market reflects deeper socioeconomic issues, where women, despite constituting a significant portion of the workforce, are more likely to be relegated to informal sector with limited protections and benefits. The high rate of self-employment among women may also indicate entrepreneurial resilience in the face of restricted access to formal jobs, capital, and education. Additionally, men's higher share of formal employment positions suggests that they benefit more from existing institutional frameworks. To bridge this gap, policies targeting gender inclusion, such as improved access to education, vocational training, and financial resources for women, are vital. Addressing these systemic barriers will not only uplift women economically but also drive overall labour productivity and national development.

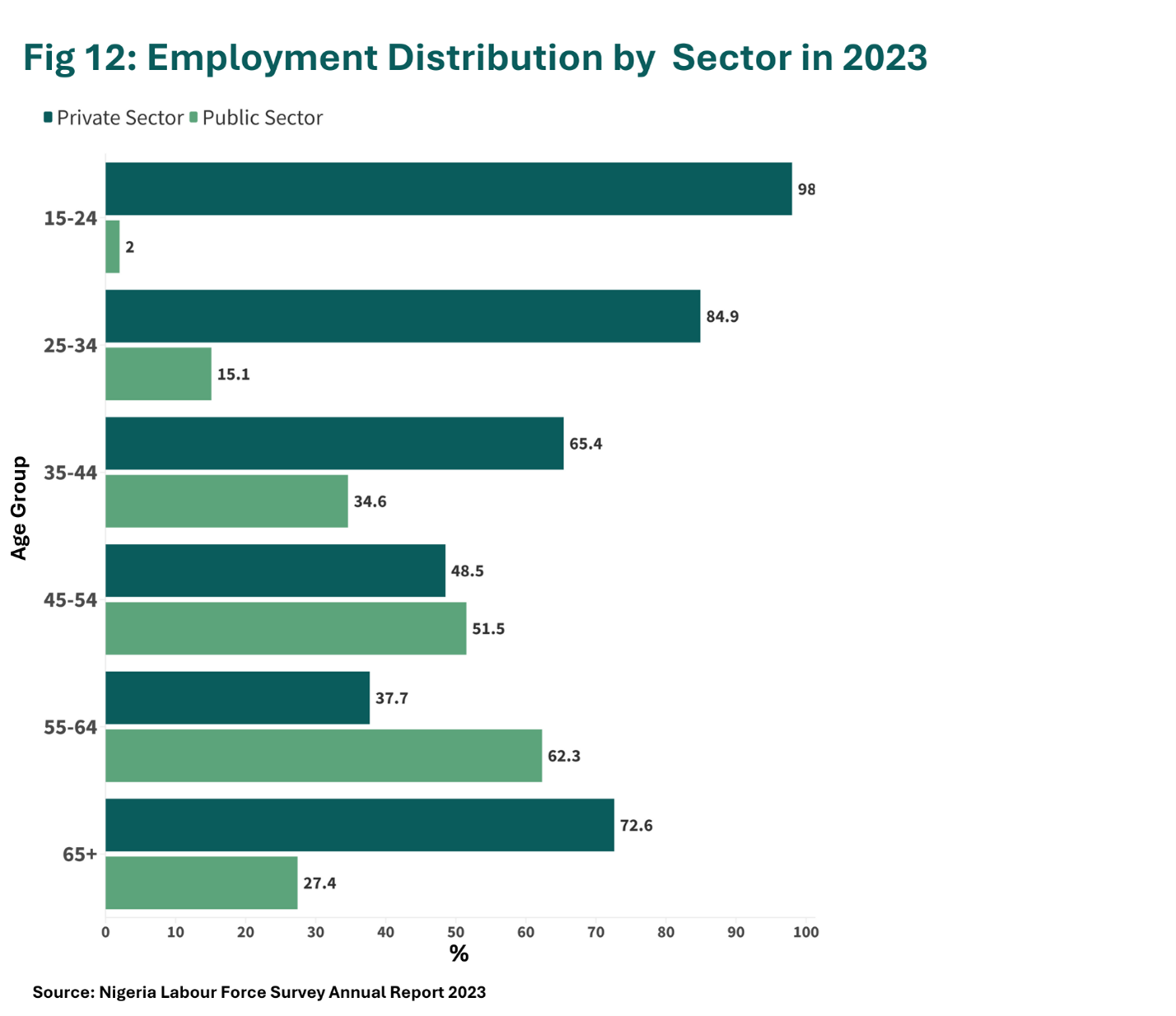

Insight 5: The Younger Population Continues to Tilt Towards Private Sector Employment

Nigeria's labour market shows a clear age-related trend in employment sector preferences, with younger workers overwhelmingly engaged in the private sector. Among the 15-24 age group, 98% work in the private sector, indicating the necessity and appeal for private sector employment over public sector employment. Many young workers find the public sector less appealing and very archaic and are likely to work in private organisations where there are technological advancements, commensurate renumerations, and periodic promotions. As workers age, their representation in the private sector decreases. Less than half (48.5%) of the workers between the age group of 45-54 years are in the private sector, while the public sector absorbs a larger share.

This shift continues into older age groups, with only 37.7% of workers aged 55-64 in the private sector. Interestingly, workers aged 65+ reverse the trend slightly, with 72.6% engaged in private sector employment, perhaps due to post-retirement entrepreneurial activities or consulting roles. These figures highlight the significant reliance on private sector employment, especially for younger and retiring populations, while the public sector appears to play a more stabilising role for mid-career professionals.

Insight 6: Agriculture Remains the Largest Employer

Agriculture continues to be the largest sector of employment in Nigeria, with 30.1% of the country's employed population working in agriculture, forestry, and fishing according to the report. This figure highlights the significant role that agriculture plays in generating employment, supporting livelihoods particularly in rural areas, and providing jobs to millions of Nigerians. However, the reliance on agriculture as the dominant source of employment also exposes certain vulnerabilities. Many of the jobs in the agricultural sector, are informal, seasonal, subsistence, and low-paying. They often lack essential social protections and leave workers in risky conditions, with limited opportunities for upward mobility. Therefore, there is a need to expand employment in other sectors such as manufacturing and technology so as to drive overall economic growth and provide more stable, high-quality jobs for the Nigerian workforce while improving productivity in the agricultural sector.

Conclusion

In this post, we have outlined some key findings from two reports of the Nigeria Labour Force Survey. Based on these insights, we propose several policy recommendations aimed at addressing the identified challenges and improving labour market outcomes. First, we recommend implementing comprehensive labour market reforms designed to strengthen the protection of workers, particularly in sectors and states where informal employment is rampant. These reforms should include efforts to formalise more jobs, introduce legal and social safeguards for workers, and ensure fair wages and benefits.

In addition, enhancing gender inclusion in the labour market is crucial. This can be achieved by improving access to education, vocational training, and financial resources for women. By equipping women with the skills and capital they need to enter and thrive in the workforce especially in formal sectors these policies can help bridge the gender gap, reduce the high levels of self-employment among women, and promote equal opportunities for both genders. Finally, expanding employment in other sectors such as manufacturing and technology can contribute to improved formal employment and provide more stable, high-quality jobs for the Nigerian workforce thereby driving economic growth.

Cover Photo: The New York Times