Blog

- Details

- Blog

By Ifetayo Idowu | The emergence of one or more forms of insecurity in nearly every region of Nigeria has pushed those regions to the frontlines of conflicts. Terrorism, herder-farmer conflicts, and ethnoreligious conflicts are all present in the North-Central and North-West regions of the country. In the North-East, Boko Haram and its affiliates are a constant thorn in the side. Militancy and economic sabotage are still present in the South-South, while ritual killings, cultism, and herder-farmer conflicts are prevalent in the South-West. In the South-East, the Eastern Security Network (ESN), the armed wing of the Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB), continues to cause death and mayhem.

Agora Policy has just released its second and most recent report, focusing on widespread insecurity on the country. Titled "Understanding and Tackling Insecurity in Nigeria,” the report examines the history, types drivers and manifestations of insecurity in Nigeria, and provides recommendations for a systemic and sustainable solution.

Impact of the Economy on Insecurity

Examining the background of the country's most prominent security issues, the report highlights how poverty and unemployment create an environment conducive to the growth of insecurity. The report states that “high incidence of poverty and unemployment expands the pool of possible recruits for criminal activities.”

In Nigeria, 39.1% of the population lives below the international poverty line of $1.90 per person per day, and an additional 31.9% have consumption levels between $1.90 and $3.20, making them susceptible to poverty in the event of even the smallest of shocks. An earlier report on the economy published by Agora Policy reported that poverty is more prevalent in rural areas, with 52% of the rural population living in poverty and with people employed in the agrarian sector more susceptible to poverty than those employed in any other sector of the economy. Based on population projections for 20211, this equates to 49,947,644 rural dwellers living in poverty.

Unemployment rate is 33.3%; while youth unemployment is 42.49%. This figure shows that almost half of Nigeria’s most productive group is economically inactive. Unemployment causes large drops in household income. In some cases, unemployment is transitory but, for many, it is a persistent risk to economic security. Unfortunately, Nigeria’s high population growth rate increases poverty and decreases employment opportunities, which in turn increases poverty. These high numbers make people more susceptible to engage in criminal activities.

Furthermore, even though insecurity is one of the results of economic pressures among Nigerians, it has also become a threat to the well-being of the same citizens. In Nigeria, insecurity is both a cause and an effect of low economic development.

Impact of the Insecurity on the economy

On October 23rd, 2022 the United States issued a security alert citing “elevated risk of terror attacks’ in parts of the country, especially the FCT. Other western nations followed suit. This subsequently led to the precautionary and temporary closure of schools, recreation centers, restaurants and other businesses. This incident shows one of the direct connections between insecurity and economic activities. Insecurity reduces economic activity, reduces revenue and fuels poverty.

Food Inflation and Banditry

Food inflation in Nigeria keeps worsening as insecurity keeps farmers away from their farms. In September 2022, food inflation in the country rose to 23.34% on a year-on-year basis. The North-West and North-Central regions of the country are responsible for the bulk of Nigeria’s food production, and these places are heavily impacted by insecurity. The fear of being kidnapped stops farmers from going to their farms, distorting planting and harvesting cycles. In other areas, farmers are paying bandits to cultivate their farms, directly affecting the quantity of food they can produce. Others, after their labour have abandoned their harvests. In the same vein, terrorists and bandits are known to raid markets for food, animals and cash to feed themselves and finance their operations. According to the National President of the All Farmers’ Association of Nigeria, the country loses 50 per cent of its food production due to insecurity. A lot of Nigeria's food shortage is caused by insecurity, which in turn makes food inflation go up.

Food transportation from the North to the other parts of the country is also an issue as food transporters face the same security challenges. Travelling across the country by road is no longer a safe option and drivers and traders are in constant fear of being kidnapped. The challenges leave farmers and their families vulnerable to poverty and hunger but this also has implications for food prices and cost of living across the country.

Economic Sabotage in the South East and South South

In the South-East, August marked exactly one year since the Eastern Security Network declared every Monday a stay-at-home holiday. The eastern part of the country, renowned for commerce, is greatly affected as no economic activity takes place on Mondays in the zone. Businesses are crumbling under the weight of this order as even customers travel to safer areas to trade. Recently, Governor Chukwuma Soludo, an economics professor and former CBN governor, stated that his state, Anambra, loses N19.6 billion every Monday due to the sit-at-home order.

Militancy, manifested in oil-theft, pipeline vandalism, piracy, illegal bunkering, kidnapping of expatriates in the Niger-Delta region has a far-reaching impact on the national economy. The Agora Policy report states;

“ apart from being largely responsible for the insecurity in the region and Nigeria's current acute energy supply crisis, militancy discourages foreign investment in new power generation plants in the Niger Delta region”.

The Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (NEITI), also reported that about $42 billion was lost to oil theft and sabotage over a ten-year period. Nigeria is the only oil-producing country not reaping benefits from the current historically high oil prices. Nigeria cannot even meet its reduced OPEC quota partly because of high level of oil theft.

Rural areas across the country are now characterised by ungoverned spaces and economic activities are restricted. Insecurity affects every sector of the economy either directly or indirectly, it leads to forced migration, displacement, food insecurity, cattle rustling, destruction of poverty and health challenges. It affects people's access to resources, incomes and freedom. Insecurity has a negative impact on economic growth by drying up investments, increasing unemployment, and decreasing government revenue.

In 2020, the Global Terrorism Index reported that economic cost of terrorism to Nigeria was 2.4% of the country’s GDP. The report also states that Nigeria incurred the largest economic impact of terrorism in the world from 2007-2019 at $142 billion.2 In 2021, Town Talk Solutions reported that projects worth N12 trillion were abandoned across the country due to insecurity. These figures have implications for job creation, government allocations and investments, purchasing power and confidence of citizens, and the country’s fight against poverty.

Recommendations in addressing Nigeria’s Security Challenges

According to the Agora Policy report on insecurity, "to stand a fighting chance in overcoming widespread and growing insecurity within its borders, the country [Nigeria] needs to adopt a more holistic approach that effectively combines tackling security threats with addressing the root causes of conflicts and agitation." Economic pressures, which fuel insecurity in Nigeria and are a challenge in and of themselves, need attention from the government. If not addressed, unemployment, particularly high youth unemployment, could exacerbate societal and security issues. In a previous report titled ``Options for Revamping the Nigerian Economy" Agora Policy made the following recommendations for improving the welfare of Nigerian citizens to reduce the economic burdens they bear:

- Prioritizing and Fine-tuning job creation strategies

- Deepening investment in critical infrastructure

- Scaling-up investment in education

- Increasing coordination across tiers of government on poverty alleviation.

Due to the complexity of the problems confronting Nigeria, the government cannot afford to address the problems in isolation. The relationship between insecurity and economic pressures makes it difficult to effectively address one issue without addressing the other. The nature of both challenges is also such they cannot not be deferred. They have to be tackled quickly and simultaneously.

*Idowu is Data/Policy Analyst at Agora Policy

Footnotes

[1]https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL?locations=NG

[2] https://visionofhumanity.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GTI-2020-web-1.pdf

- Details

- Blog

By David Nwachukwu | Nigeria is an eerie example of the relationship between climate change and insecurity. Nigeria’s location in both the Sahel region of Africa and along the coastal line of West Africa increasingly makes the country vulnerable to climate shocks from the north and the south. The Lake Chad basin, a major lifeline for millions of people living in the Sahel, has notably shrunk by 90 percent since the 1960s.Drought and desertification have increased in recent years, negatively impacting the arid northern states. Coastal erosion and flooding are now frequently experienced in Lagos, Kogi, Benue and other states, due to high precipitation, among other reasons.

These climate shocks negatively impact not just life and livelihoods but also contribute to struggles and conflicts over arable land and water. The latest report by Agora Policy, ‘Understanding and Tackling Insecurity in Nigeria,’ rightly identifies climate change as a much-overlooked driver of conflict in Africa’s most populous nation.

As world leaders converge in Egypt this month for the 27th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27), climate activists can expect a plethora of pledges from each country aimed at tackling the reduction of carbon emissions. For Nigeria to reduce its vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change, government agencies must accelerate their plans for adaptation and mitigation by implementing holistic solutions to climate-related security issues. Doing this well will also assist Nigeria in tackling its security challenges.

It is estimated that in the past 15 years alone, the number of deaths in the Sahel has increased by more than a thousand percent as a result of the competition for the region's dwindling supplies of water and food. Insurgent groups like Boko Haram seek to take advantage of the fact that 30 million people in Nigeria, Chad, Niger, and Cameroon are all vying for the same limited water resources. Recent ecological threat reports point out how terror groups in charge of water supply can charge an already vulnerable population a fee to use limited supply, using it as leverage to conscript them, or even use their need for water as an excuse to forcibly enlist members.

Young girls and women are disproportionately affected by this while carrying out domestic duties, taking long walks in search of water– often facing the great risk of abduction and sexual assault. Nigeria's security situation is exacerbated by its porous borders, which allow for unchecked/unsupervised entry into the country, making people in Northern Nigerian communities even more susceptible to attacks.

The harmful effects of climate change pose immense risks to the lives, livelihoods and well-being of communities across West Africa. Despite making the least contributions to the global climate crisis– emitting just 0.51% of total greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) the region remains one of the biggest victims of its ghastly impacts, bearing an unfair burden of the global north’s mistakes.

Socioeconomic Impacts of Climate Insecurity

The massive loss of livelihoods to climate disasters puts even greater pressure on the national economy. Two-thirds of the global poor are reported to be from Sub-Saharan Africa, with Nigeria recording the highest number of poor people living within the region. The World Bank has recently estimated the number of citizens living in poverty will reach 95.1 million by the end of 2022. Climate-related shocks such as the country’s recent flooding crisis have displaced over two million citizens to date, damaging over a million acres of the nation’s farmlands.

By proxy, the impact of these catastrophic floods further escalates an already existing food crisis, as 2022 marks the second consecutive year when Nigeria ranks 103rd on the Global Hunger Index (GHI). Before experiencing the worst deluge in over a decade, rain-fed farming patterns were already changing due to unpredictable weather conditions– making temperatures rise and fall drastically during dry seasons and pushing farm households to adapt their livelihoods to new conditions.

With pastoral communities losing land and water resources to environmental decay, many are forced to become climate migrants in search of sustenance, where they are pushed south towards central farmlands. This shift creates a scuffle for limited resources leading to conflict. The long-standing conflict between farmers and herdsmen has escalated dramatically in the Middle Belt, a central region in Nigeria, as herdsmen have been forced to migrate south from their traditional grazing lands as a result of drought. This pattern is reflected in different parts of the country, including the North West, South West and the South East.

The recent report on insecurity by Agora Policy points out how clashes between farmers and herders over land have spurred the formation of ethnic militias, vigilante raids, and extrajudicial killings across Adamawa, Benue, Taraba, Plateau, Kaduna and other states. According to the report, land available for open grazing in Nigeria's Middle Belt declined by 38 per cent between 1975 and 2013, while the area dedicated to farming nearly trebled.

Elsewhere, climate migration significantly impacts security in the country’s major urban centres. The massive influx of displaced persons presents a problem in addressing issues of housing, employment and increased pollution. In the absence of available jobs and access to reasonable living conditions, displaced persons often turn to crime, illicit drug use and other scrupulous activities. Those living in peri-urban communities face the threat of being attacked by a vulnerable population that yields to the indoctrination of terrorist/militant groups.

Need for A Multidimensional Nature-Based Approach

It is advisable for policymakers to embrace a multidimensional approach to tackling this crisis. Going beyond the policies for sustainable development within Nigeria’s recently launched 2021 Climate Act, there is also a need for solutions tailored to the issues plaguing hotspots of conflict. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) recommends that countries should enhance their preparedness for identifying, preventing and responding to climate-related security risks.

The report by Agora Policy has a number of recommendations along this line. One of these is a thorough review of Nigeria’s Land Use Act (1978). Review of this law is critical to the resolution of ongoing herder-farmer conflicts that hold resources ransom. Another recommendation is that government-proposed plans such as The National Livestock Transformation Plan (NLTP) and the National Pasture Development Programme (NAPDEP) should be much more transparent and inclusive to better address the concerns and needs of other citizens affected by these issues.

Additionally, enhancing the role of traditional justice mechanisms can also play a great role in managing the agitations brought by land disputes and communal conflicts, which are direct results of the degradation in Northern states brought on by climate change. There are also prospects for the Nigerian economy through climate financing, which would help the country’s mitigation and adaptation efforts in vulnerable sectors like agriculture and the power sector. Given the varied drivers and manifestations of insecurity identified in the report, it is important for policymakers to address root causes like climate change through holistic approaches.

*Nwachukwu is a Communication Officer at Agora Policy

- Details

- Blog

By Mohammed Shuaibu | Globally, international trade and investment flows are regarded as strong enablers of sustained inclusive growth and development. Countries with more liberal trade and investment policies tend to grow faster, innovate more, produce more, have higher incomes, and create more opportunities. Although globalisation has ushered in an era of economic prosperity around the world, some developing economies like Nigeria have not taken full advantage of the opportunities created.

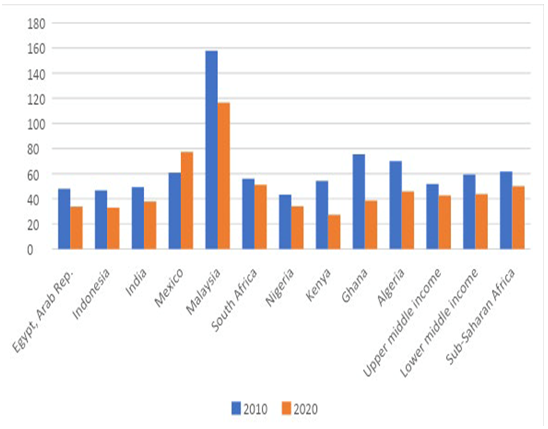

Higher trade openness could help stimulate industrialisation and economic diversity. However, Nigeria’s trade history is skewed towards a restrictive trade policy stance. This stance has been primarily motivated by the need to protect some sectors, increase domestic production, ensure security (preventing the smuggling of arms and ammunition), and attain self-sufficiency in food production. The government has deployed various tariff and non-tariff barriers such as import bans and other economic policies such as multiple exchange rate windows, foreign exchange restrictions, and border closure that have significantly disrupted trade flows. These policies are the result of the wariness of trade liberalisation by some critical stakeholders whose scepticism derives from concerns about unfair competition that could stifle domestic companies. Trade as a share of GDP in Nigeria declined from 43% in 2010 to 34% in 2019 making it one of the lowest among peer countries.

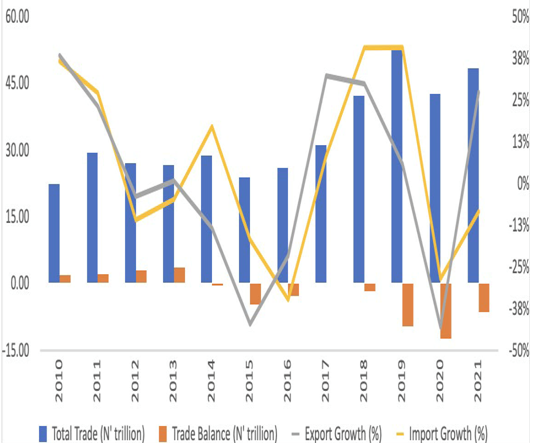

A major characteristic of Nigeria’s trade performance over the last decade is persistent deficits. Trade balance moved from a surplus of N2.14 trillion in 2011 to deficits of N4.51 trillion in 2015 and N2.61trillion in 2016, largely due to the oil shock and weak foreign exchange management that led to a recession (Figure1). Despite modest improvements in the trade deficit in 2017 and 2018, it increased to N12.25 trillion in 2020, and N6.31 trillion in 2021. While the performance of total trade was largely stagnant between 2011 (N29.38 trillion)and 2017 (N31.15 trillion), it increased to N52.4 trillion in 2019, and N42.6 trillion in 2020 followed by a rise to N48.36 trillion in 2021 (Figure 1). The growth of exports and imports has been quite volatile in the last decade, with exports largely driven by global oil market conditions and imports constrained by a poor exchange rate management strategy and a restrictive trade policy environment.

Fig 1: Trade volatility is driven by oil shocks

Source: CBN BOP Statistics

The last few years have witnessed a significant resurgence of protection with an escalation of trade barriers. These include higher tariffs, levies, and import bans on some commodities that can be produced domestically such as rice, sugar, and cassava. These trade policy distortions combined with recent global developments such as the slow recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine crisis continue to amplify risks.

Furthermore, the non-oil sectors that are crucial for Nigeria’s diversification with potential for job creation have remained largely unexplored due to supply-side constraints that have been worsened by an unfavourable trade policy environment. The agriculture and manufacturing sectors, for example, have not been optimally harnessed especially with the dominance of the oil sector which has further dampened prospects and crowded out non-oil sectors (See Fig 3). The low value-added of these sectors has contributed to the country’s vulnerability to oil price shocks and consequently, foreign exchange shortages.

Fig2: Low trade openness in Nigeria relative to peer countries

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators online

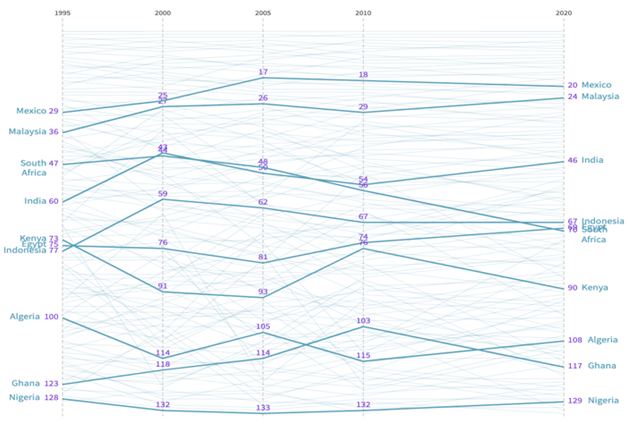

Note: Endpoint (2020) for Nigeria based on 2019 value

Oil sector dominance of Nigeria’s trade over the last five decades has translated to its very low economic complexity relative to peer countries (Figure 4). The economic complexity index gauges the state of an economy’s productive knowledge and is improved by increasing the number and complexity of the products they successfully export.1 Therefore, a robust trade policy and investment environment that promotes export diversity and sophistication could help address these gaps, create jobs, and inclusively transform the economy. Yet, the trade policy environment is dominated by restrictive policies which do not bode well for export diversification, capital inflows, and inclusive development. Trade supports economic growth through investment, competitiveness and technology transfer channels by creating jobs, improving domestic value-added and reducing domestic prices.

Fig 3: Oil Sector dominance in trade

Restrictive trade policies inhibit investment inflows and their positive effect on the economy.2 This is because trade barriers could encourage market power (monopoly) which is associated with inefficiency, higher prices, technology transfer and knowledge spill overs required to spur inclusive development. The investment climate in Nigeria is largely liberal, with 100% foreign ownership allowed in all sectors except the oil and gas sector. Investments in this sector are limited to joint ventures or production-sharing arrangements, with a minimum ownership structure of 55% for the government. Foreign investors must be registered as limited liability companies. Two recent important legislations are expected to improve the business and investment environment. The first is the Finance Act 2019 which provides tax incentives for businesses, and the second is the Companies and Allied Matters Act (CAMA) 2020 which simplifies and provides additional clarity for setting up businesses in the country especially micro, small, and medium small-scale enterprises. However, structural challenges, macroeconomic policy instability, and insecurity have, interalia, constrained investment inflows to Nigeria.

Fig 4: Economic complexity in Nigeria is very low relative to peer countries3

A comprehensive long-term trade policy agenda can help drive sustainable growth. This will require robust monitoring and evaluation systems to gauge the implementation of regional and multilateral trade initiatives such as the Africa Continental Free Trade Area Agreement (AfCFTA). Nigeria is currently participating in the AfCFTA negotiations and therefore, the trade policy discourse, especially around rules of origin, services trade, and intellectual property amongst other outstanding issues is critical. At the same time, reforming the tariff regime and service restrictions would help enhance competitiveness. This would entail simplification of import duties and gradual liberalisation of the service sector given its potential to create jobs and stimulate the transfer of knowledge which can drive non-oil sector growth.

Furthermore, distortionary non-tariff measures need to be urgently revisited and phased out completely. These include: (i) the foreign exchange restrictions on 42 products by the CBN; (ii) a review of the import prohibition and absolute import prohibition lists and perhaps replacing these trade policy tools with tariff duties or import quotas; (iii) change in government policy on border closure from partial reopening to the full reopening of closed land borders.

Modernisation of ports and custom infrastructure is critical for a successful trade and investment reform. Despite modest improvement in port and customs operations, there is still a lot more that can be done to enhance efficiency and optimal service delivery. Urgently addressing trade facilitation constraints ranging from cumbersome customs procedures to congested ports are crucial for the success of trade reforms. This would require standardisation of procedures, strengthening the e-governance portal towards paperless transactions, and establishing a functional grievance and redress mechanism for stakeholders. This means that bold reforms are required by the Nigeria Customs Service (NCS) such as the implementation of the e-Customs modernisation plan and the National Single Window (NSW) platform that can improve trade facilitation. Also, critical investments through public-private partnerships would be required to help address port congestions and delays.

Reducing oil sector dominance in the economy and building up the sector’s value chain would help drive economic diversity while counter-productive waivers and informal leakages that reduce public and private investment in export-oriented sectors need to be revised. This entails nipping supply-side constraints in the bud to shift from oil to high-value-added agriculture and manufactured products. This could be achieved by creating an enabling business environment devoid of contemporaneous discretionary measures that inhibit trade flows such as border closure, foreign exchange restrictions, and import bans.

Trade and investment flows could play an important role in revamping the Nigerian economy. However, their potency will depend on the right complementarity of macroeconomic policies and structural reforms that can support trade and investment. Realizing the need to develop a medium to a long-term trade policy plan that prioritizes diversification is critical. Recalibrating the trade policy thrust by shifting from distortionary non-tariff to tariff measures could also help while efforts to accelerate port and custom reforms are required. The institutional path used to implement the right mix of complementary reforms could help Nigeria maximize the gains from trade and investment. This should be predicated on good governance in terms of efficiency, sustainability and equity.

*Dr. Shuaibu is a Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Abuja. He is one of the authors of Agora Policy’s report on “Options for Revamping Nigeria’s Economy.”

Footnotes

[1]https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/rankings

[2]https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/rankings

[3]https://atlas.cid.harvard.edu/rankings

- Details

- Blog

By Babajide Fowowe | Federal Government’s total debt stock at the end of the second quarter of 2022 was N35.672 trillion. This comprised N14.723 trillion in external debt and N20.948 trillion in domestic debt.

- Details

- Blog

By Ifetayo Idowu | Poverty and unemployment are some of the most spoken about challenges in Nigeria. That’s why they are both recurring campaign topics.