By Tayo Agunbiade | The results of the recently-held general election have once again confirmed the continued under-representation and marginalisation of women in politics and governance in Nigeria. Women constitute 49.3%of Nigeria’s total population, but only manage to secure 4.69% of the executive and legislative positions on offer at the federal and state levels in the elections held between February and March this year. The country’s highest law-making and decision-making bodies are thus guaranteed to remain excessively male-dominated for another four years. Deliberate policy and other steps must be taken to address this imbalance in the immediate and in the medium to long terms.

At the federal and state levels, Nigeria has a total of 1,534 electable positions. This is broken down as follows: two President and Vice President; 72 state governors and deputy governors; 469 federal legislators (made up of 109 senators and 360 members of the House of Representatives); and 991 members of the states’ Houses of Assembly. Out of these, women won only 72 positions in the 2023 general election. This amounts to a paltry 4.69% of the total executive and legislative positions on offer in the 7th electoral cycle in the 4th Republic, which commenced in 1999.

Of the 72 women elected in 2023, seven are deputy governors while the remaining 65 are federal and state legislators. On the bright side, there is a marginal increase over the performance of women in the 2019 electoral cycle when only 66 women were elected in all, with only four being deputy governors. This shows that overall female representation improved by 9.09% while the number of deputy governors increased by 75%. Also, there are some states, like Kwara, where female legislators in the state parliament shot up by 500%. However, these marginal gains are diluted by reversals at the federal parliament and maintenance of the gender status quo among the president, the vice president and state governors.

Great Expectations, Grim Results

There was an expectation that women would fare better in the 2023 electoral cycle. There has been a consistent increase in women’s interest and participation in Nigeria’s political and electoral fields. This awareness has also spilled over to civil society and over the years there has been high-level advocacy for more female representation in political and electoral leadership. So, what went wrong for the Nigeria’s female candidates?

For the presidential race, there was a drop in the number of female candidates seeking to occupy Aso Rock. This time around there was only one candidate namely: Ms Chichi Ojei of the Allied Peoples’ Movement (APM). This was a reduction from six women who featured on the ballot paper as presidential candidates in the 2019 election. The reason for this is due tothe fact that in 2019, there were 91 political parties, and many of them, unlike the older parties,welcomed women to contest in the presidential election on their platforms. To date, none of the older and main political parties have presented a woman candidate for the top posts of president and vice-president.

With the exception of Adamawa State, the male-centric culture adopted by most of the main parties on electable executive positions was replicated in the candidacy for the gubernatorial race. History was made in the state when for the first time a woman-Senator Aisha Dahiru, popularly known as Binani- was selected to run on the platform of aruling national party, the All Progressives Congress (APC).Indeed, it must be stated that this is the second time APC would select a woman as its gubernatorial candidatein North-East geo-political zone. In 2015, late Senator Aisha Jummai Al-Hassan was the party’s gubernatorial candidate in Taraba State.

There were also a handful of women as governorship candidates on the platforms of relatively smaller parties such as Binta Umar of the Action Alliance from Jigawa State; Hajiya Fatima Abubakar of the African Democratic Congress (ADC) in Borno State; Beatrice Itubor of the Labour Party (LP) in Rivers State; and Khadijah Iya Abdullahi of All Progressive Grand Alliance (APGA) in Niger State. This too is commendable. But regardless of this and by all standards, this electoral journey has proved to be a disappointment for women in Nigeria.

As is known, legislative institutions are at the heart of a democracy and globally there is vigorous consciousness about the importance of women’s agency and voices in law-making. Nigerian women are part of the groundswell of global advocacy for participation, representation and inclusion in national and state parliaments.

The number of women who contested for seats in the federal legislature was 380 (8.9%), out of a total of 4,223 candidates. A closer look at the breakdown of the candidates to the upper and lower chambers shows the following: Of the 1,101 candidates to the Senate, 92 were women; while there were 288 women of a total of 3,122 candidates for the House of Representatives. Only three of 92 women candidates won seats to the 109-seat Senate and 14 out of 288 to the 360-member House of Representatives. This means a total of 17 women will occupy seats in the 469-member National Assembly.

It is interesting to note that about 96% of the female contestants for the federal parliament did not win. This has been the trend. In 2019, 95.5 % of the contestants to the National Assembly suffered electoral losses, while in 2015, 94% of female candidates failed to win seats. This tells us the magnitude of defeat being experienced by women during the past few election cycles.

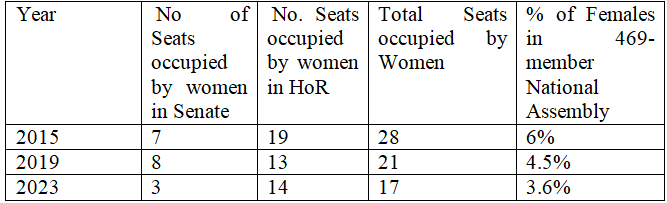

The critical issue at the other end of the spectrum is the drop in the number of seats occupied by women in the National Assembly. For the 10th National Assembly, female representation stands at 3.6%. In 2019, there were 21 women legislators (4.5%) and 28 (6%) in 2015. The data also points to the fact that women’s interests, voices and perspectives across the country will continue to be excluded and marginalised in the making of national legislation and the constitution review exercises.

One of the consequences of under-representation is the low success rate of women-related legislations. It will be recalled that the Gender and Equitable Opportunities Bill sponsored by Senator Biodun Olujimi is yet to pass through legislative hurdles since it was first presented in 2015. It was voted down based on reasons which include religion and culture as stated by some male legislators.

In 2021, Hon. Nkeiruka Onyejeocha alongside 85 other legislators in the House of Representatives sponsored an amendment to the 1999 Constitution to create additional 111 seats which will be exclusively for women in the National Assembly. Although the bill passed its second reading, but overtime, it failed to garner the required support.

The most recent instance of how low representation negatively impacts women-related legislations occurred on 8thMarch 2022, when five Gender Bills which were drafted to amongst other things increase inclusion and representation of women in governance, were roundly rejected during the constitution alteration exercise. The bills address women’s rights, indigeneship, citizenship and affirmative action in appointments, as well as the executive committees of political parties and reserved seats for women in national and state assemblies. Yet there was a concerted effort on the part of several male lawmakers to see that none of these bills see the light of day. This was despite the fact that all 21 women legislators were members of the Constitution Review Committees set up by each chamber of the National Assembly.

Table 1 below shows the gender landscape of Nigeria’s federal legislature from 2015 to 2023 and highlights the extent of male domination of this national deliberative institution.

Table 1: Gender Landscape of 469-Seat National Assembly (2015-2023)

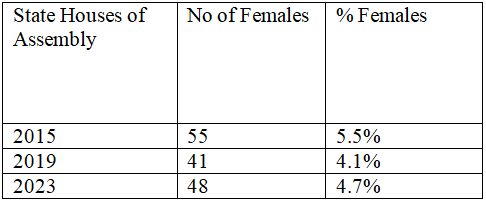

The outcome of the electoral race at the state level was no different.Of the 10, 231 contestants to the State Houses of Assembly, only 1,019 (9.9%) were women of which only 48 won seats to the 991-member State legislature. This indicates a success rate of a paltry 4.71% for female candidates at the state level. Besides the data revealing a 95.28% electoral loss at this level for women candidates, it also shows that there is only a negligible increase of seats in comparison with 2019. Women gained only seven seats more than the 41 won in 2019, to record a slight increment of 4.1 % to 4.7 %.

Table 2 below shows the gender landscape of Nigeria’s state legislature from 2015 to 2023 and also highlights the extent of male domination at the state level.

Table 2: Gender Landscape of 991 State Houses of Assembly (2015-2023)

As indicated in Table 2, the overall landscape in the state parliaments is similar to that which prevails at the national level, even though this legislature is generally regarded as being closer to the grassroots communities.

Mixed Results at State Level

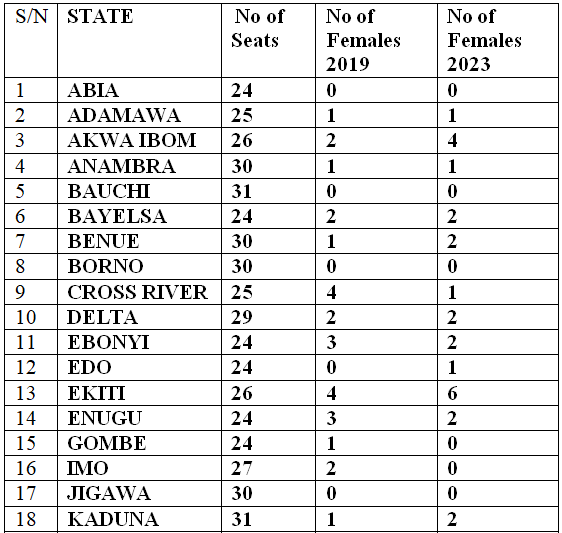

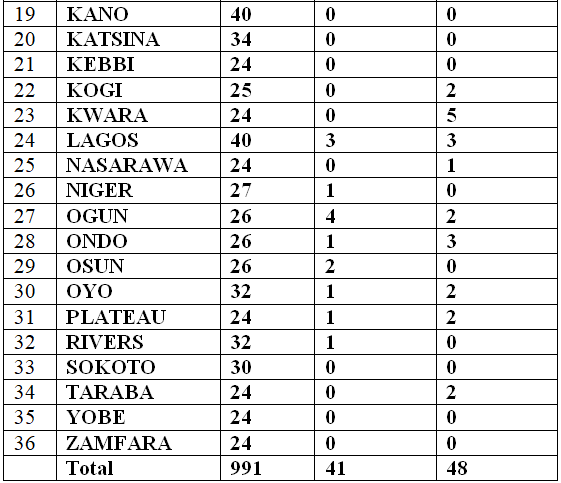

Notwithstanding the deepening gender gap in the legislative arm of government, some history has also been recorded at the sub-national level which must be hailed. For example, worthy of note is the fact that for the first time, the elections have produced a handful of women to the Houses of Assembly in the northern states of Kwara, Taraba and Kogi.

Indeed, Kwara State in North-Central Nigeria has for the first time recorded five women in its 24-seat Assembly. This is the second highest number of women, after Ekiti State in South-West Nigeria which has six out of 26 members. Against the backdrop of women’s share in the number of seats in past, these are milestones.

Marginal increases occurred in several states. For example, Ondo State went from one to three female lawmakers; Kaduna and Plateau both went from one to two; and Edo and Nasarawa went from zero to one each. Akwa Ibom went from two to four female lawmakers; while others like Bayelsa and Delta maintain their status quo of two female legislators each.

States such as Imo, Gombe, Niger and Rivers where previously there were a handful of female state legislators, are now left with none. Others like Cross River, Ebonyi, Enugu and Ogun saw a slight drop in their previous numbers. For example, Cross River went down from four women to one; Ebonyi from three to two women, and Ogun from four women to two.

Table 3 below provides the data of women in the State Houses of Assembly for 2019 and 2023.

Table 3: Female Representation in State Houses of Assembly (2019-2023)

Source: Dailytrust.com

Of the thirty-six states, fifteen states have no female representation in their Houses of Assembly for the in-coming legislative tenure. The states with zero female legislators in their houses of assembly are: Abia, Bauchi, Borno, Gombe, Imo, Jigawa, Kano, Kebbi, Katsina, Niger, Osun, Rivers, Sokoto, Yobe and Zamfara. In the out-going tenure of 2019-2023, a similar number of states do not have female representation. They are: Abia, Bauchi, Borno, Edo, Jigawa, Kano, Katsina, Kebbi, Kogi, Kwara, Nasarawa, Sokoto, Taraba, Yobe and Zamfara.

Undoubtedly, there is a general decline in women’s electoral fortunes from the perspective of representation. The total number of women in both legislatures in 2019 and 2023 underscores this fact. In 2019 for the joint federal and state legislatures of 1,460 seats, there were 62 women (4.3%); while in 2023, only 65 women will sit in the federal and state legislatures (4.5%). Overall, this is a very marginal improvement in the number of women within public decision-making between 2019 and 2023. The marginal wins and heavy losses at the ballot box show that much more needs to be done to address the hurdles encountered by female politicians.

In terms of female parliamentarians, Nigeria lags on the continent. Rwanda has the highest proportion of seats held by women at 61.25%, which is also the highest figure in the world. In other parts of Africa, South Africa, Namibia and Uganda have 46%, 44% and 34% female parliamentarians respectively. In West Africa, Senegal has the highest number of women in its national parliament at 42.4% of the seats. Guinea and Mali have 29.63% and 26.45% respectively. Republic of Niger has 26%, Benin Republic, 25%, Togo, 18.7% Ghana, 14.5%, Sierra Leone, 12.33%, Cote d’Ivoire, 12.5%, Liberia, 10.96%, Gambia 8.6% and Burkina Faso has 6.3%. Nigeria, the largest country in the sub-region has the lowest number of women in parliament at 3.6%.

Some Reasons Why Women Lose at the Polls

To be sure, it is not the lack of participation per se that has caused the loss on such a scale by female contestants and left state institutions largely male dominated. There are other societal influences that hinder women from achieving the desired electoral results and over the years, there have been deep discussions about these factors.

Possibly the most pressing challenge to Nigeria’s electoral democracy is monetisation of politics and vote-buying. This is a recurring problem which has not been adequately addressed by the law. Among other provisions, sections85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90 in the 2022 Electoral Act list: offences in relation to finances of a political party; period to be covered in annual statement; power to limit contributions to a political party; and limitations on election expenses of political parties etc. Butthe lack of enforcement continues to blight the political and electoral system.

Similarly, the Electoral Act does not have any provisions to address the lack of inclusion of women in political party hierarchies and candidates’ nomination and selection lists. Nigeria’s electoral laws must be strengthened to become more inclusive and INEC as the agency at the helm of electoral matters must through diligent enforcement, ensure total compliance.

Women politicians are also subjected to a variety of other factors which also includes bias in the media, god-fatherism, trado-cultural and religious barriers and so on. Similarly, election violence has seen loss of lives and destruction of property. For example, some women have lost their lives before, during and after elections. The reported cases of Emily Aborishade, Joyce Maimuna Katai, Salome Abuh and Emilia Gilbert from Ekiti, Nasarawa, Kogi and Rivers states respectively, and mor

e recently, Victoria Chintex in Kaduna State, come to mind. These killings must not be swept under the carpet, and perpetrators of all acts of violence must be held accountable. It is important to make the environment safe for all candidates, especially marginalised groups like women.

Historical Precedence and Patterns of Political Exclusion

Historically, women have been excluded and marginalised in electoral politics, public decision-making institutions, constitution-drafting and governance in general. Hence, for further insights, it is relevant to trace the roots of women’s under-representation in political leadership and elective representation back in history.

This pattern of imbalance can be directly linked to the British colonial era, when provisions in the 1922 Clifford Constitution stated that elections to the Legislative Council of Nigeria were for “Every male person who is a British subject or a native of the Protectorate of Nigeria, who is of the age of twenty-one years or upwards…”

This set off a process which saw Nigeria’s electoral and political party systems being built on male power and authority. There was collusion between the forms of colonial and indigenous patriarchy which saw colonial statutes and ordinances such as the one mentioned above, suit the male hegemony culture already being exhibited by early nationalists who excluded women from their mainstream political structures.

From then on, the evidence points to the over-representation of men in public life and domination of the political party structures, attendance of constitutional conferences and so on.

The early political parties such as the Nigerian National Democratic Party and the Nigerian Youth Movement built and nurtured systems which were centred round male political aspirations, interests and needs, with the women’s sections left to deal with mundane matters. With each wave of political parties from the nationalist era through to the First, Second, Third and the current Fourth republics, political institutions remain largely male-centric.

The historical evidence shows that during the 1950s, the new constitutions (Macpherson of 1951 and Lyttleton of 1954) allowed limited franchise for female taxpayers and later on, universal suffrage for everyone in the Eastern and Western regions of Nigeria. However, those women who were eligible to participate and contest in elections faced stiff resistance from their male colleagues. Indeed, this may account for why Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti is quoted as saying, her failure to win at the intermediate round of the Electoral College in 1951 was due to “male chauvinism.” Again, in June 1957, she reiterated this point in a statement to the press that “Women are used as election tools.”

During Nigeria’s First Republic from 1960 to 1965, only four women won elections. They were Margaret Ekpo, Janet Mokelu and Ekpo Young to the Eastern House of Assembly and Esther Soyannwo to the Western House of Assembly. Each woman is on record as having to stave off resistance by their male political associates. Thus, there is a historical pattern of systemic male bias and overwhelming exclusion of women from the country’s politics and governance, which as the data shows, still exists today.

Recommendations

As the data shows, despite their share of the population, women are being politically short-changed in the executive and legislative arms of government. There are wide gaps between the number of men and women who govern, hold positions of political leadership and occupy seats in the federal and state legislatures.

The answer to women’s substantive representation in the country’s public life lies in several measures. To reverse the continued marginalisation of women in politics and governance, the next administration should undertake the following:

- Conduct a forensic review on the status of women vis-à-vis their massive loss at the polls from 2015 to now, as well as their overall participation and representation in public affairs;

- Implement the April6,2022, Federal High Court ruling on 35% Affirmative Action in favour of women;

- Appoint an equal number of female and male ministers, or at the minimum, implement the 35% affirmative action for women in line with the ruling mentioned above;

- Ensure that the women are placed in substantive ministerial postsincluding those perceived to be traditional male portfolios.

- Implement and enforce the revised National Gender Policy 2021- 2026. Its key planks are designed to promote gender equality, political leadership and social inclusion across the three tiers of government. This is to address the massive losses experienced by women in the past three elections.

- Make social inclusion a key plank of its administration

- Provide (through an Executive Bill) the legal framework for the National Gender Policy for compliance and to ensure its enforceability

- Explore the principle of proportional representation to ensure that women who got as far as the ballot box are included in federal and state governments

- Promote a caucus of male gender champions in the parties, state and national assemblies to promote gender-responsive legislation;

- Promote the He-for-She Movement into an effective and vibrant coalition across religious and political divides;

- Sponsor legislations ontemporary special mechanism by the 10th National Assemblysuch as reserved seats for women in state and federal legislative institutions. This is known to work and has boosted women’s representation in legislatures in Europe, Latin America and United Kingdom. Closer to home, this kind of quota system has significantly altered parliamentary landscapes in South Africa, Tunisia, Namibia and Mozambique etc;

- Influence the reversal of all of the five rejected Gender Bills mentioned above, so they can be passed and signed into law by the president towards the socio-political empowerment and growth of girls and women;

- Pass the Gender and Equitable Opportunities Bill 2021 and alsoensure appropriate budgeting in order to effect to its implementation;

- Lead by example in the ruling party and then persuade other political parties to adopt gender quotas in their executive organisational and hierarchical structures as recommended by Uwais Report in 2007. In South Africa, the African National Congress (ANC) has perfected its voluntary party quota system and women form significant representation in its parliament.

Other stakeholders should also:

- Gender advocates must work on nomenclature that would be embraced by faith and culture leaders, so pursuance of gender-friendly legislation will face less resistance

- Conduct enlightenment programmes about the meaning of Gender Equality and its benefits for the empowerment of girls, women and Nigerians in general;

- Build a coalition of women (like in Senegal to achieve the Parity Law) across party lines and CSOs to organise, strategise to diminish the shadow of political, electoral and traditional patriarchy;

- Build on the positive wave of some political parties towards women’s representation in the governorship elections and lead by further example in local government councils;

- Reform the composition of Constitution Amendment/Alteration Exercises to make it more inclusive and reflect Nigeria’s population in order to achieve favourable constitutional guarantees for girls and women;

- INEC should consider sponsoring amendments to the 2022 Electoral Act which will ensure promotion and compliance of inclusivity on political party quotas and candidates’ lists etc;

- Work with journalists to eliminate bias of all forms against women politicians in traditional and social media spaces.

*Mrs Agunbiade, journalist, historian and gender advocate, is the author of the book: ‘Emerging from the Margins: Women’s Experiences in Colonial and Contemporary Nigerian History’

Sources:

- Dailytrust.com,Meet 48 Women who made it to state assemblies,’Saturday March 23, 2023

- International IDEA, https://www.idea.int

- https://www.inecnigeria.org

- Premiumtimes.ng,IWD 2023: Nigeria falling in women’s political participation, March 10, 2023

- Statista: Percentage of women in national parliaments in African countries 2022, www.statista.com

- Women Data Hub https://data.unwomen.org

- Women Liberty and Development Initiative, 2019