By Adele Jinadu | The problem of corruption in Nigeria is fundamentally a problem of democratic political governance and has to be approached as such in view of its negative consequences for human development in the country, as outlined in Chapter II of the country’s constitutions since 1979. The political nature of the problem of corruption is clearly underscored in the principles of the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption (AUCPCC).[1]

But if corruption is a problem, it is also so because it is a symptom of the generally anti-democratic political and legal culture and the impunity that pervades our country’s public life. Amorality, the failure to distinguish between good and bad behaviour, seems to be on the loose in the country. It is as if we have lost our moral bearings, as if moral rules do not matter, and as if we care less about what is right and what is wrong. This is why character and integrity, as elements of the social capital needed to weld us together as a moral community, are glaringly missing in our political leadership recruitment process. It is a saddening development.

Box I: Principles of the AUCPCC

My point in starting off in this manner is to underscore the thrust of this keynote address. I want to weave a large picture of the deepening moral decay in virtually all our institutions, secular and religious, and in state and society. We have become prey to a crass materialism that only serves to debase us as citizens. This approach is dictated by my own interest in the philosophical, mainly ethical issues raised by the general desecration, so obvious in our public political life today, of the public interest notion of politics in our country. Doing so, I want to address a missing link, a lacuna in our current discussion of the problem of corruption in our country. This missing link is our failure to address the current crisis of democracy, development and federalism in our country as also fundamentally a moral problem through an analytic framework, which seeks the explanation for the crisis in the yawning gap between, on the one hand, our practice of democracy and federalism and, on the other hand, the public interest morality, laid out in Chapter II of Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution and on which our democratic politics must be firmly anchored.

The navigational compass for this approach is my belief that democratic politics, which is really about a peopled-centred and inclusive public policy, is pre-eminently applied ethics or moral philosophy in practice. This leads me to the observation that the moral or ethical environment in which we now pursue our democratic politics is not directed towards the promotion of the public interest. The overwhelming crisis of democracy in our country must be sought in an anti-democratic political culture, for which constitutional and legal reform alone is insufficient, despite all the emphasis and energy devoted to it.

This is particularly so with our anti-corruption policy and practice, and with the thrust of our anti-corruption legislations. Therefore, we “build in vain,” if we approach the crisis of democracy and development in Nigeria, of which corruption is symptomatic, only or primarily as an economic or technicist, or law and order one, reduced to economic growth and statistical computations, important as they are. We must also seriously address, confront and mitigate the corrosive effect of our country’s toxic even diabolic moral and political environment in stultifying our democratic development, without which we cannot advance our democracy or build development as human development, defined not narrowly as economic development, or count our success in the anti-corruption war in terms of the increasing number of convictions for corruption of high-profile elected and other public officers.

What Is the Problem About Corruption?

What does all of this have to do with the state of anti- corruption policy and practice in Nigeria? What is corruption, and what is the problem about it?[2] Corruption has a general immoral connotation that connects it with the perversion of what is “good.”[3] Thus, Leys suggests that “What is at issue in all …cases [of corruption]…is the existence of a standard of behaviour according to which the action in question breaks some rule, written or unwritten, about the proper purposes to which a public office or a public institution may be put….”[4] The African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption (AUCPCC),[5] under Section 1, defines “corruption” as “the acts and practices, including related offences proscribed in this Convention.” In subsequent chapters, it itemises the following as offences covered by the Convention: bribery (domestic or foreign), diversion of property by public officials, trading influence, illicit enrichment, laundering of proceeds of corruption, and concealment of property.

However, the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) refrains from providing a single definition of corruption. Instead, it focuses on identifying specific acts of corruption that should be established as criminal offences by every state adhering to the convention. This approach is a response to the inherent difficulty of determining a comprehensive definition of corruption due to its diverse manifestations at the national, regional and global levels. The UNCAC establishes measures to prevent and combat corruption in five main chapters: Preventive measures; Criminalisation and law enforcement; International cooperation; Asset recovery; Technical assistance, and information exchange.”[6]

No matter its definition, and situated within the broader public space and public policy-making process, corruption—as understood in the AUCPCC and UNCAC—diminishes civic virtue, an important element in democratic theory. It cannot be generalised or universalised. In short, the condemnation of corruption in politics, what I call political corruption, has generally been framed in terms of some higher moral purpose or values. In other words, in terms of the public interest which public policy should promote, protect, and, therefore, discourage and punish, if violated, to prevent society from disintegrating or reverting to Thomas Hobbes’ hypothetical state of nature. Otherwise, to universalise corruption as a form of acceptable behaviour will weaken trust and integrity as an important form of social capital necessary to hold the fabric of society together.

Civic duty converts self-interest into enlightened self-interest. For this reason, corruption is viewed and, therefore, rejected as an undesirable prescription to inform public policy formulation in a democracy. For this reason, democracies such as Nigeria, have constitutional provisions for Code of Conduct for Public Officers, and for Oaths of Office to be sworn by each of the president, governors, members of the National Assembly, and members of the State House of Assembly.[7] Specifically, in this respect, the 1999 Constitution of Nigeria under Section 15 (b) provides that “the state shall abolish all corrupt practices and abuse of power,” while the Fifth Schedule, Part 1, of the provides a Code of Conduct for Public Officers.

Yet, beyond the statutory provisions that proscribe corrupt practices and provide for punishment to deter them, the problem of corruption connects with wider philosophical issues in ethics, relating to the meaning of moral concepts such as Good, Duty, Conscience, and Justice, and over whether there can be “honest graft” or forms of corruption that are permissible because of their good consequences. Or, are there instances of corrupt behaviour and types of corruption, for example, lying, that are permissible and justifiable on grounds of “reason of state,” and understandably exculpatory if they serve a higher moral end or public intertest? Are there or can there be acts of public corruption that are not blameworthy if subjected to cost-benefit analysis? For example, is there some redeeming feature and, therefore, some good, in specific acts of political corruption, if, as some contend, they can be shown to have contributed to economic and social development, through the recirculation of their proceeds to provide jobs, social amenities, and public utilities for communities and not stashed abroad but are put to productive use within the country?[8] Does or can the means ever justify the end?[9]

To pose these questions is to explore the complex dimensions of the nature and the role of morality in shaping public policy reform. Intertwined with such questions are those about the limits of law in enforcing morality and as an instrument for facilitating social change. We need to understand and emphasize the strong connection between morality, law and politics, especially, the contradictions arising from their interface, and the limits of law to enforce morality, if we are to understand and explain why political corruption in public life remains a problem, not only in Nigeria but also in other democratic countries. This is what Jean-Jacques Rousseau particularly but other philosophers before and after him, foretold about the Janus-faced character of human nature in politics when, in proposing a Constitution for Poland, he argues as follows:

“Although it is easy, if you wish, to make better laws, it is impossible to make them such that the passions of men will not abuse them as they abused the laws which preceded them. To foresee and weigh all future abuses is perhaps beyond the powers even of the most consummate statesman. The subjecting of man to law is a problem in politics which I liken to that of the squaring of the circle in geometry. Solve this problem well, and the government based on your solution will be good and free from abuses. But until then you may rest assured that, wherever you think you are establishing the rule of law, it is men who will do the ruling. There will never be a good and solid constitution unless the law reigns over the hearts of the citizens; as long as the power of legislation is insufficient to accomplish this, laws will always be evaded. But how can hearts be reached? That is a question to which our law-reformers, who never look beyond coercion and punishments, pay hardly any attention; and it is a question to the solving of which material rewards would perhaps be equally ineffective. Even the most upright justice is insufficient; for justice, like health, is a good which is enjoyed without being felt, which inspires no enthusiasm, and the value of which is felt only after it has been lost. How then is it possible to move the hearts of men, and to make them love the fatherland and its laws? Dare I say it? Through children's games; through institutions which seem idle and frivolous to superficial men, but which form cherished habits and invincible attachments. If I seem extravagant on this point, I am at least whole-hearted; for I admit that my folly appears to me under the guise of perfect reason.” [Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Considerations on the Government of Poland, Chapter I, 1765, pp.3-4]

The Roots and Mechanisms of Political Corruption

The deep root of the general democratic governance and development crisis of our country, of which political corruption is symptomatic, is to be sought in the fact that the connection between democratic politics and democratic political and legal culture is gravely absent in our country. The absence has nurtured and continues to feed a pervasive political culture of impunity across all facets of institutional life in state and society in our country. In other words, the significant light that Rousseau’s argument throws on the problem of political corruption is that we need to begin to address, in addition to the use of the law to proscribe it, we must also turn our reform lenses away from the belief in constitutional review and judicial policymaking and legislation as the magic to solve it. Instead, we should view and approach it, keeping in mind Rousseau’s dicta that (a) “…those who would like to treat politics and ethics separately will never understand anything about either of them;.”[10] And (b) “…it is only when the voice of duty replaces physical impulse and right supplants appetite that man, who up till then had considered only himself, finds that he is forced to act on different principles, and to consult his reason before listening to his inclinations.”[11]

The tragedy of our democratic politics and the underlying causative roots of the problem of corruption is that our political class continues to push its self-interest, almost to the point not only of their own self-destruction but also of stultifying our national development. What we need to do now is to bring morality back into our politics and firmly reject the politics of immorality that is at the heart of our country’s problem of corruption. We must not be blinded by the characteristic pretence of our political class whey they engage, as they often do, in the doublespeak that Claude Ake referred to as defensive radicalism, and that Hegel, speaking of the German political class of his time, described in the following words, “…they become accustomed either to a constant contradiction between their words and the facts or else to an attempt to make events different from what they really are and to twist their explanations of them to suit certain concepts.”[12]

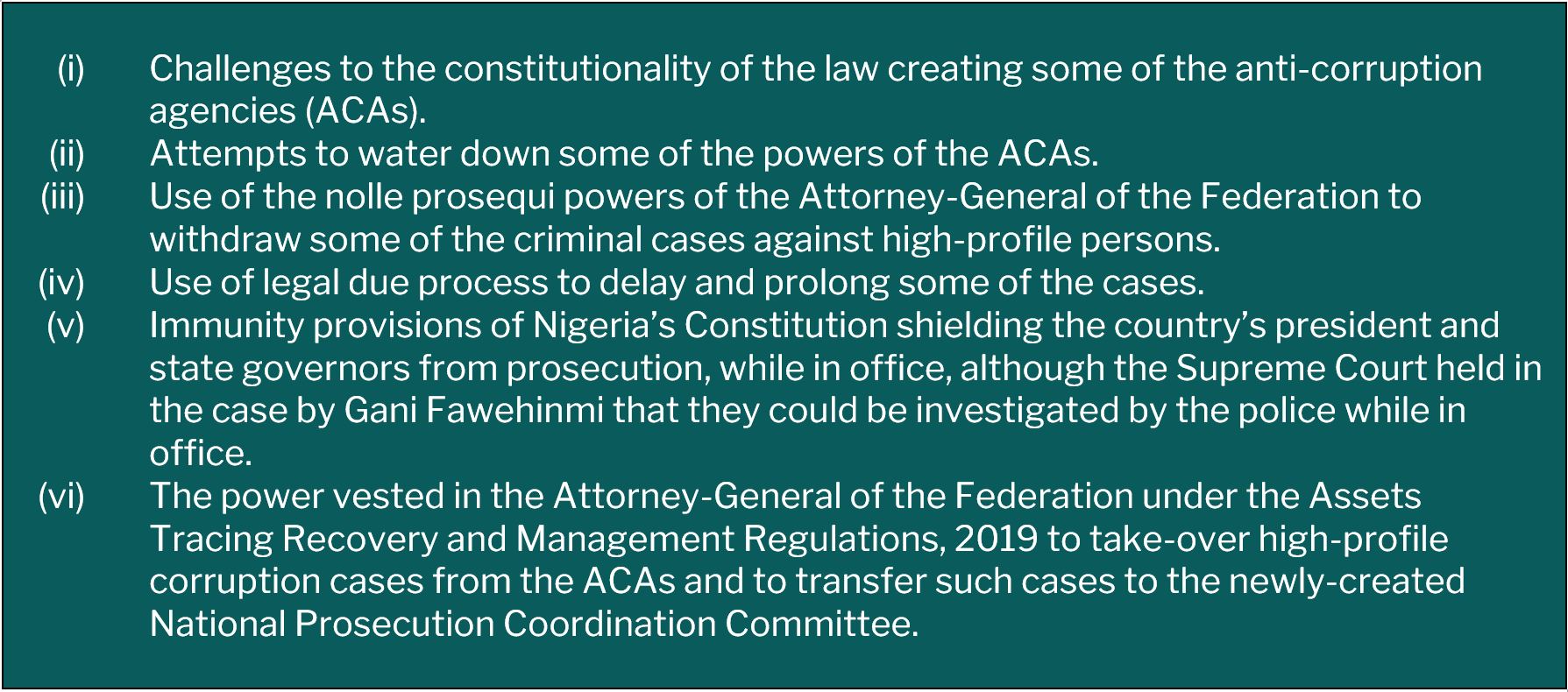

The anti-democratic culture driving the country’s policy-framework and diabolic political environment, notably in the form of political interference, primarily to shield high-profile persons from criminal prosecution or to frustrate their prosecution has impacted negatively on the country’s anti-corruption agenda, despite the establishment of the National Anti-Corruption Strategy(NACS) in July 2017.[13] The result is that the country’s national anti-corruption strategies and policy measures have neither significantly dented nor prevented the deepening of grand larceny in the country. As a 2021 Nigerian Bureau of Statistics study concludes, “While the prevalence of administrative, mainly low-value, bribery has decreased, the survey results suggest that the government’s anti-corruption agenda, which tends to be focused on large-scale corruption, has so far only marginally affected this type of bribe-seeking behaviour.”[14] Examples of the form the political interference has taken include the following itemised in Box II.

Box II: Forms of Interference with the Work of Nigeria’s Anti-Corruption Agencies

How do we explain why we are now where we are, weighed down, seemingly helpless and virtually immobilised by the burdensome weight of political corruption? The excepts in Box III from a study conducted between 2006 and 2012 on understanding political leadership commitment to governance reform in the following 10 states (Anambra, Enugu, Jigawa, Kaduna, Kano, Katsina, Lagos, Niger, Yobe and Zamfara), to which I had privileged access, paints a grim picture of the governance and policy environment that drives political corruption in Nigeria.

Box III: Weak Political Commitment to Governance Reform in Nigeria

But how did we get there? It is a long story dating back to the beginnings of responsible and cabinet government under the 1951 Macpherson Constitution, and over which the colonial administration expressed grave concerns, as a result of the increasing use of political power for corrupt personal enrichment, for corruptly building an electoral war chest, and for corruptly sustaining political clientelism in the country’s three regions, because of their foreboding signposts for the future of democracy in an independent Nigeria.[15] The “Skeleton Plan: Nigeria,” submitted to the Colonial Office in March 1957, was one among many internal memoranda that pointed to the dangers of the large-scale abuse of the power of incumbency to gain partisan party electoral advantage and “to intimidate and coerce their opponents” by governing political parties in the three regions.[16]

The abuse of the power of incumbency has reached disturbing heights of impunity in our country’s Fourth Republic. The worst form of political corruption, the abuse of the power of incumbency fuels other forms of corruption in the country. It makes nonsense of the ex-ante indeterminacy of democratic elections, the possibility of today’s winners becoming tomorrow’s losers and the possibility of today’s losers becoming tomorrow’s winners in our politics of electoral succession. It goes against the grain of Section 15(5) of our 1999 Constitution that provides that “the state shall abolish all corrupt practices and abuse of power,” and Item 9 of the Fifth Schedule of the that provides that, “A public officer shall not direct or direct to be done, in abuse of his office, any arbitrary act prejudicial to the rights of any other person knowing that such an act is unlawful…” The now commonplace and, indeed, routinised abuse of the power of incumbency for partisan electoral gain feeds on a wider political culture of a zero-sum approach to politics that encourages the fusion, not separation of politics from administration. It gravely breaches the separation of powers, moderated by checks and balances, among the branches of government. Its consequence is to convert the executive branch at the federal and particularly at the state level into a monarchy or imperial executive branch.

Two other developments that underscore the contradictions of democracy and federalism in our country point to the limitations of the magic of constitutional and legal reform in fighting political corruption. The first is our country’s failure, despite the over-legislation and over-judicialization of our competitive party and electoral politics and process to rein in the irresponsibility and seeming incorrigibility of our political parties in violating competition rules, such as those relating to party primaries and party and election financing, for unproblematic political succession with abandon.

The second development revolves around the way in which horizontal, democracy-promoting institutions, such as the Code of Conduct Bureau, and the INEC, established as Federal Executive bodies under the Constitution; and the EFCC, ICPC, NHRC, are established by law--all designed collectively as a fourth branch of government to ensure ethics, accountability and transparency in public political life and in the private sector---continue to be generally perceived as constrained in pursuit of their mandates by interference from the executive branch and the legislature. Nothing reflects better the perception of political interference, particularly by the executive branch and, to some extent the legislature, on the anti-corruption war than the chequered tenure of past chairpersons of the country EFCC, some forced out, some suspended or some removed before the end of their tenure, or whose confirmation was held up or turned down by the legislature, as illustrated in Table I.

Table I: EFCC Chairpersons, 2003-2024

“What Is to Be Done?” Some Navigational Aids

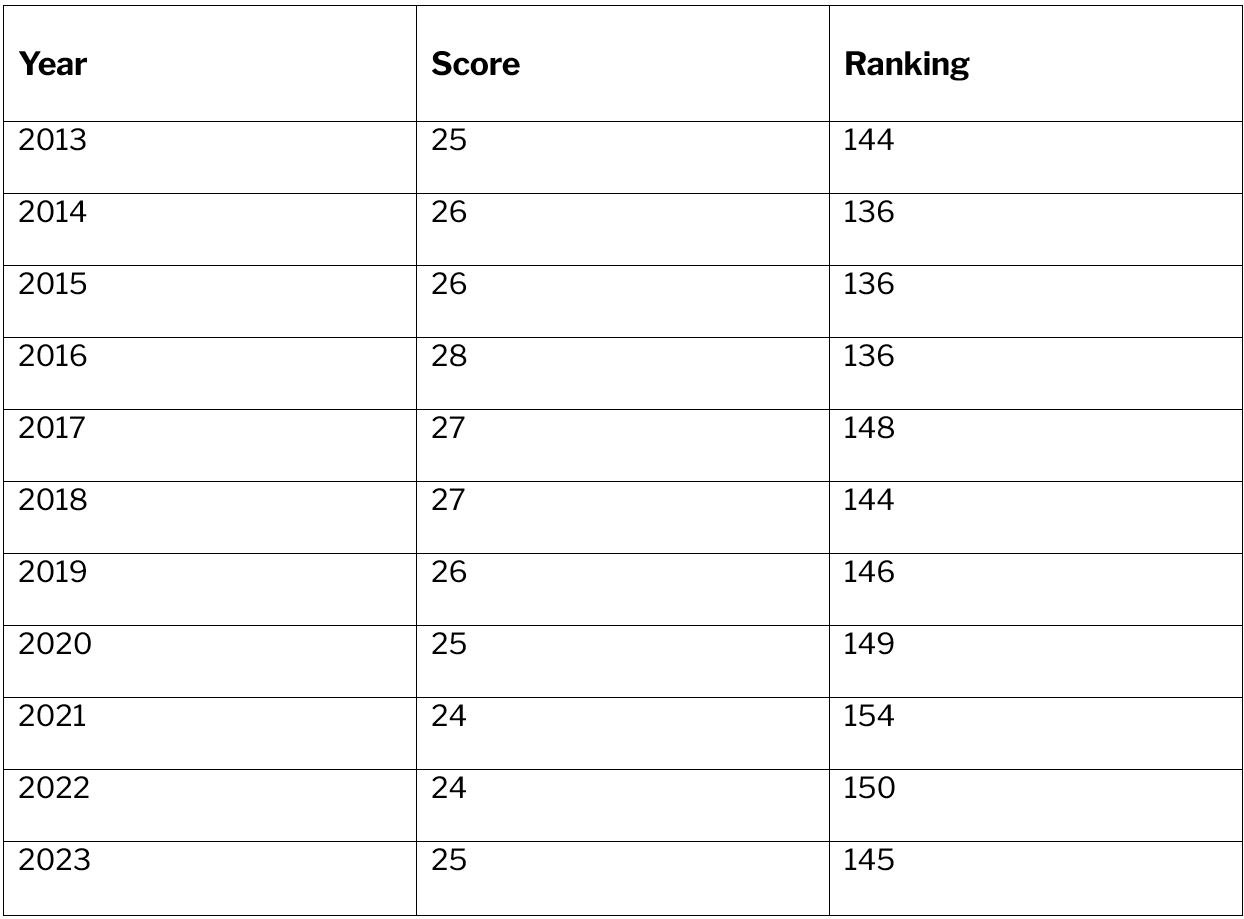

Nigeria’s poor score and ranking on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) between 2013 and 2023 [Table II], despite the remarkable success recorded by the country’s anti-corruption agencies in securing convictions of high-profile public officers and recovery of huge sums of looted money property,[17] is worrisome.

Table II: Nigeria’s CPI Score and Ranking, 2013-2023

The country’s anti-corruption agenda must look beyond the episodic reform of the legal and political framework for prosecuting the anti-corruption agenda, desirable and unavoidable as it is, to link it more firmly and vigorously to a broader framework of political reform agenda anchored on mandate protection, as envisioned in Section 29, Duties of the Citizen, of Chapter II of Nigeria’s 1999 Constitution. I now offer a sketch of some navigational aids about what is to be done to address some of the missing links in our country’s anti-corruption policy and practice that I identified in earlier sections of this address. The assumptions framing the navigational aids are (a) rehabilitation of democracy and federalism in the country by anchoring their practice more enduringly on the core ethical vocation of politics as a public trust; and (b) creation of many layers of decentralised and autonomous public authorities, affording our local communities the opportunity for self-government.

In short, my choice of the navigational aids and policy framework is premised on the need, in addition to rehabilitating politics as a moral force for social change and social justice, to (a) promote and actualise the public welfare, through structural and institutional reforms, which impose a social obligation on the state, as opposed to market forces and the private sector, as the prime allocator of social surplus, and (b) deepen the democracy and federalism in the country by rehabilitating and actualising the entrenched constitutional provisions in Chapter 2 of the country’s constitution relating to the sovereignty of the people and the duties of the citizen.

How do we proceed along this line?

First, we must begin a process of reforming our legal system in fundamental ways, and away from their excessive formalism and elitist bias, in order to engender a more progressive, activist and public interest legal culture, which will provide legal anchor for social and distributive justice as state policy. We must, as is now being done in India through judicial interpretations, strengthen Chapter 2 of the Nigerian Constitution by making the fundamental objectives and directive principles of state policy enshrined in it gradually justiciable, especially regarding the responsibility of the state to provide security broadly defined as human development. Secondly, there must be a reform of the country’s party system. As presently constituted, this party system is at the centre of a vast oligarchic and clientelist spoils system, which sustains and reinforces patron-client political relationships in the country.

Thirdly, there is need to strengthen such horizontal institutions of accountability and transparency as the Code of Conduct Bureau, INEC, the Central Bank, the Human Rights Commission, Public Complaints Commissions, the ICPC and the EFCC. This requires that the mode of enabling or appointing their members/commissioners, their tenure, in other words how they get disabled, and the sources of funding for the institutions/agencies should be insulated from partisan politics, and made genuinely independent of political officeholders, over whom they are to exercise oversight.

The appointment of their members should be until retirement age, except for cause, as for judges,; it should be done and their operations supervised by an institution similar to Plato’s Nocturnal Council, a small group made up largely of distinguished, non-partisan, noetic personalities drawn from various spheres of our national life, whose function is to rescue the public interest from the rampaging clutches of the country’s political class, and to whom these oversight institutions shall be accountable and responsible. Recent experience with the operations of a number of these oversight institutions suggests that they are merely extensions of an imperial presidency, that they are immersed in partisan politics, and that they are too readily disposed to abandon due process in carrying out their oversight functions.

Fourthly, there is need to bring about what, in India, has been described as “the democratisation of political information and opinions, as a public investment in the democratic knowledge enterprise,” aimed at disseminating information about public matters, to the general public on a regular basis. To this end, the right to information should be entrenched in the constitution, to ensure greater accountability and transparency in public political life. The reform is also essential to institutionalise a wider process of popular participation in the political process.

Fifthly, we must look beyond the political class and the political parties to create political and social institutional networks or subsidiary associations, made up of professional and non-governmental organisations and community groups to assert peoples’ power, which, if and when, imperative will mobilise mass political action to resist reckless anti-people policies and impunity by our administrative and political authorities. In addition to this, as a long-term investment, we need to adopt in the short- to- long-term a reform of our educational system at all levels, focusing on pedagogical as much on substantive curricular review to create the foundations of the moral reorientation or revolution to drive politics and development as public interest projects.

The objective must be targeted at encouraging and conscientizing citizens to become good citizens who have internalised civic virtue and responsibility as a categorical moral imperative. The metaphor of a night watchman captures the essence of this approach.

The Night watchman approach should be anchored on the following four interlocked policy reform issues:[18]:

- Rights of Citizens: Cultural and socio-economic rights, provided under Chapter II of the Constitution of Nigeria, in addition to the customary civil and political rights under Chapter 1V.

- Limits to State Power (or separation of administration from politics): Rule of Law and mechanisms for oversight of abuse of state power through constitutionally provided and guaranteed countervailing forces and institutions in state and society, including the private sector, and other guardrails of democracy to check abuse of state power and impunity by public authorities. [Chapters IV, V, VI, VII of Nigeria’s Constitution]

- People’s Agency: people’s agency, as provided under Chapter II, Section 14(1), and Section 14(2)(a)(b)(c) of Nigeria’s Constitution, notably: presidential, gubernatorial, National Assembly and state Houses of Assembly elections; also under Chapter IV, enumerated right to: a) freedom of thought; freedom of expression; freedom of peaceful assembly and association; c) freedom of movement; freedom from discrimination, subject to provisions of Chapter IV, Section 45; and

- Political Accountability: The “duty and responsibility all organs of government, and of all authorities and persons exercising legislative, executive or judicial powers” to citizens as provided under Nigeria’s constitution; and the role of the following independent, democracy-promoting commissions to monitor and ensure compliance with political and related accountability provisions of the country’s constitution in governance: EFCC, Human Rights Commission, ICPC, INEC; Code of Conduct Bureau; and the Public Complaints Commission.

The message of this keynote is that “eternal vigilance is the price of liberty. Let the sentinels on the watch-tower sleep not, and slumber not.”[19] Nurturing such nightwatchman civic virtue is an indispensable and durable guardrail against the political culture of impunity of our elective political office-holders.

*Professor Liasu Adele Jinadu, a Senior Fellow of the Centre for Democracy and Development, wrote this paper as a keynote address for the policy conversation on ‘The State of Anticorruption Policy and Practice in Nigeria’ organised by Agora Policy, CDD and CFTPI with the support of the MacArthur Foundation, and held in Abuja, Nigeria on 10th December 2024.

[1] The AUCPCC was adopted in Mozambique on 11 July 2002 and came into force on 5 August 2006. Nigeria signed the AUCPCC on 16 December 2003; ratified it on 26 September 2006; and deposited it with the AU on 29 December 2006.

[2] See accessed December 5, 2024

[3] But “good” as a moral concept is itself a subject of philosophical contestation. See Alasdair MacIntyre, A Short History of Ethics,” ch.2, and 18

[4] Colin Leys, “What is the Problem about Corruption?” The Journal of Modern African Studies, p.221

[5]. The AUCPCC was adopted in Mozambique on 11 July 2002 and came into force on 5 August 2006. Nigeria signed the AUCPCC on 16 December, 2003; ratified it on 26 September 2006; and deposited it with the AU on 29 December 2006.

[6] See, https://www.unodoc.org/corruption/en/learn/what-is-corruption.html, accessed 6 December 2024.

[7] The Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999, Fitfth Schedule and Sixth Schedule.

[8] Leys, op. cit.

[9] See for a discussion of some of these questions, Susan Mendus, Politics and Morality, Polity, 2009; Stuart Hampshire (Ed.), Public and Private Morality, Cambridge University Press, 1978; and G.J. Warnock, Contemporary Moral Philosophy, Macmillan, 1967

[10] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Emile

[11] Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract, 1, viii

[12] Quoted in Nevil Johnson, [1977] In Search of the British Constitution: Reflections on State and Society in Britain,. Pergamon, 1977, p. 193

[13] Idayat Hassan, The EFCC and ICPC in Nigeria: overlapping mandates and duplication of effort in the fight against corruption, ACE Working Paper 038, November 2021, .

[15]. See Robert L. Tignor, “Political Corruption in Nigeria Before Independence,” The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol.31, No. 2, 1993, pp175-202

[16] Martin Lynn (ed.), Nigeria, Part II: Moving to Independence, 1953-1960, British Documents on the End of Empire, , Section B, Volume 7, London: The Stationery Office, 2001, pp.375-384

[17] For 2022 convictions, see https://www.efcc.gov.ng/efcc/images/pdfs/3785_Convictions+recorded+in_2022.pdf Accessed December 10, 2024

[18]. For fuller elaboration, see Centre for Democracy and Development, Towards Post-2019 Election Reform in Nigeria: Concept Note, 2020

[19] Article in Virginia Free Press and Farmers’ Repository, May 2, 1883, quoted in www.thisdayinquotes.com/2011/01/eternal-vigilance-is-price-of-liberty/html