![]() By Bolaji Abdullahi | The students’ loan scheme is, arguably, the flagship education policy of President Bola Tinubu in his first year in office. However, by focusing only on the loans without bringing the entire issue of higher education funding into full focus, government has only paid attention to the branch, rather than the tree itself.

By Bolaji Abdullahi | The students’ loan scheme is, arguably, the flagship education policy of President Bola Tinubu in his first year in office. However, by focusing only on the loans without bringing the entire issue of higher education funding into full focus, government has only paid attention to the branch, rather than the tree itself.

On 12thJune 2023, within days of assuming office, President Tinubu signed into law the Students Loan (Access to Higher Education) Bill, 2023. The law was to provide interest-free loans to students in publicly owned higher education institutions in the country. While the action was generally well received, it was also dogged by a few criticisms. One major criticism was that only students whose family income is below N500, 000 per annum would qualify for the loan. Even in a country where the majority have been reported to live below the poverty line, this would exclude almost everyone able to desire higher education. Another important criticism of the law was that the loan was meant for only tuition payment. However, given that public higher educational institutions in Nigeria do not charge tuition, the legislation appeared to have overlooked the financial burden that the students actually carry, which include cost of living and sundry charges and levies. There were a few other issues with the law in terms of governance and administration of the loan system itself.

Therefore, when in March 2024 the president sent a new bill to the National Assembly seeking to repeal and re-enact the Students Loan Act2023, many thought it was in reaction to these identified shortcomings. Although sending the law for repeal at a time that implementation ought to have started generated a few grumblings and gave ammunition to some critics, it was actually a plus for the government. By not persisting with the implementation of the flawed 2023 law, the president was able to project himself as being responsive to public opinion and to demonstrate that his government was actually interested in getting the scheme right. Moreover, the speed with which the repeal and the re-enactment process was completed (in less than three weeks—from March 14 to April 4) signalled the seriousness that the government attaches to the bill. Perhaps, more importantly, it also indicates that the president has the National Assembly with him on this score.

The Students Loan (Access to Higher Education Repeal and Re-enactment) Act 2024 is a significant improvement on the earlier law, which in retrospect now appeared rushed for the purpose of scoring early political points with the vocal segment of the youth population. Under the new law, all students of publicly-owned higher educational institutions and government-approved vocational and skills acquisition centres can now access the loan, regardless of the economic circumstance of their parents. Also, they can use the loan to pay for other things apart from tuition. Vicarious liability clauses have also been removed in the new law, as each student is now solely responsible for repaying their loans, which commences two years after national service or exception from it, at the rate of 10 percent of income, provided the individual has a job or is self-employed. However, unlike the previous law which explicitly described the loan as interest-free, the new law implies that interests will be charged on the loans, but without stating the percentage[1].

Perhaps, the most important amendment to the law is in its governance structure. The 2024 Act establishes the Nigeria Education Loan Fund (NELFUND) as an enterprise-minded corporate body. Although it would receive its funds from 1% of revenue accruable to the government from the Federal Inland Revenue Services (FIRS) as well as from legislative appropriations, the fund is also free to transact business and trade in both movable and immovable assets. The announcement of the renowned banker, Mr. Jim Ovia, as the chairman of the fund on April 26, would also be seen as a reflection of NELFUND’s business-facing orientation.

At the launch of the fund, President Tinubu remarked that “no one, no matter how poor their background, should be excluded from quality education and opportunity to build their future.” This statement by the president indicates that the loan is intended to address the issue of social equity by making it easier for children from poor families to pay for higher education. This statement betrays a misdiagnosis of the problem of public higher education today or over the time. Besides, the history of student loan, either in this country or elsewhere, does not support the enthusiasm and the hope expressed by the president on the stated intention of the policy.

The Student Loan Scheme: A Troubled History

One of the first African countries to introduce a student loan scheme was Ghana in 1971. This initiative was however, short-lived as it was abandoned the following year as a result of a change in government. The scheme was later reintroduced in 1975 under other names as ‘education credits’ or ‘repayable financial assistance’ because of the negative connotation that the word ‘loan’ had acquired in the first incarnation of the scheme. Regardless of the nomenclature, the scheme was designed to help students buy books and pay for living expenses. A university Students Loan Scheme was also introduced in Kenya in 1974. Earlier, in 1972, the had joined the train[2].

Decree No. 25, establishing the Nigerian Students Loans Board (NSLB),was promulgated in 1972 and the Board itself was inaugurated in 1973. Although tuition was free in all the higher institutions, and boarding and medical services were subsidised, students still had to pay in full for feeding and other sundry expenses. The loan was therefore intended to assist indigent Nigerian students in the country’s higher institutions to complete their education. However, in 1976, Decree No. 25 was amended via Decree No. 21 to extend the loans to Nigerians studying outside the country.

By 1991, the NSLB had awarded loans amounting to about N46 million ($4,600, 000), but was able to recover only N6 million ($600, 000) or only 13 percent of the loans[3]. In explaining the abysmal recovery record, Joseph Chuta, Executive Secretary of the board, identified three main factors: “loopholes” in the decree that the defaulters and their guarantors were able to exploit to evade responsibility; inability of the board to cope with the administrative needs of increasing demands and; perception of the loan as a “national cake”, which created disincentive for repayment[4].

On account of some of these challenges, the Students Loans Board Decree No. 12 of 1988 was promulgated. To overcome some of the administrative challenge, the 1988 decree decentralised the process of award and loan recovery by establishing zonal offices in Bauchi (North), Akure (West) and Port Harcourt (East) to support the headquarters in Abuja, as well as area offices in all state capitals. It also opened two international centres in New York and London for overseas students. The decree also introduced a few other provisions. Academic institutions were now required to confirm an applicant as a bonafide student before loans could be granted. This suggests that people who were not students were able to access the loan in the past. The decree also set a maximum limit on the amount that could be awarded to both local and foreign students.

Despite these legal and administrative tinkering, there was no reported evidence that the loan scheme functioned any better, especially in terms of recovery. Perhaps, the sub-optimal, if not outright failure of the loan scheme, caused the Federal Government to propose a major step-change in its approach to student education financing. The country already had the Mortgage Bank for those who would like to borrow for housing and the Bank of Agriculture for farmers. People’s Bank had also been created for petty traders. So, why not create an education bank?

Proponents of the education bank had argued that unlike the loan board that was another government parastatal, the education bank, as a body corporate, would not only be free of undue political interference, but it would also be able to invest in other businesses and carry out normal banking services so it would not rely perpetually on government subventions. It was equally argued that in addition to granting loans for educational purposes, the bank could also finance research, publications and workshops, as well as “do all such things as may be deemed incidental or conducive to the attainment of efficient educational investment[5].”

The education bank didn’t take off. Therefore, it is difficult to say if it would have delivered better results than the students’ loan board. However, given that the other schemes that inspired it had not been of sterling success themselves, it would be safe to assume that the proposed education bank would not have made any significant difference

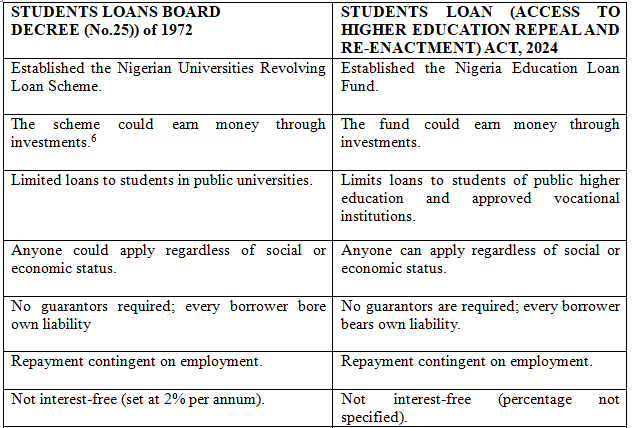

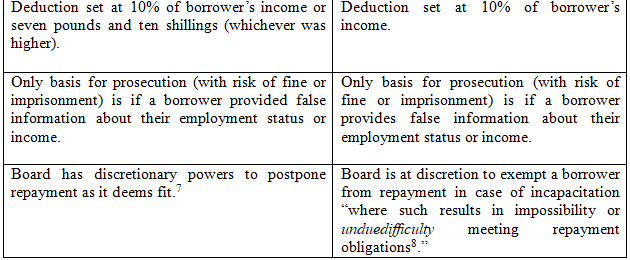

If the operators of the current initiative on students’ loan are familiar with this history, they should feel very uneasy, given how the current scheme appears to replicate the earlier failed attempts, at least in terms of the legal and operational framework. A comparison of the 2024 Act and the 1972 Decree No.25, even without examining their operative contexts, shows remarkable similarity between the two laws.

Table 1. Comparing Decree No.25 of 1972 and Students Loan Act, 2024.

Earlier, we identified three factors that caused the failure of the student loans scheme under Decree No.25 of 1972. The three factors could be summarised as administrative, legal and political. Decree No. 12 of 1988 was brought in to address these issues. But those same issues are still prevalent today, perhaps in their more virulent forms. In 1972, there were only six universities in the country, which increased to 27 (federal and state) by 1988, with a total enrolment of 159, 677 students[9]. Yet, it was difficult to manage the number of applications to the student loans board. Today, with a total of 91 federal and state universities and enrolment estimated at close to two million, it is easy to imagine how difficult it would be to process the avalanche of applications that will ensue. Of course, we now have computers, but this may not really make much difference in a country notoriously deficient in managing processes.

The second factor was the legal loopholes that borrowers were able to exploit. Those same gaping holes are noticeable in the current law. For example, as noted in Table 1 above, Section 3(b) allows the board to waive repayment for anyone deemed to be “incapacitated” in a manner that repayment becomes unduly difficult. One can understand the intention behind provisions such as this. Other countries with longer and better history of student loans also have provisions that allow for debt forgiveness or waivers. But in our own case, it is easy to see how it could provide an escape route to those who will not want to pay.

If the borrowers of student loans under the military could view it as a ‘national cake’, it can safely be assumed that those borrowing under a democratic regime would also see it as ‘dividends of democracy.’ When and if the government seeks re-election, the temptation becomes ever higher for people to treat the loans as political largesse. And, needless to say, if the military government could not enforce repayment, what would a democratically-elected government do if too many people are defaulting?

Perhaps, the chief problem with education loan, whether granted by a board or a bank, is the bad collateral. A bank can recover a house or a vehicle from a defaulting borrower, but education cannot be recovered. Also, making repayment contingent on employment is the right thing to do. But whether it is the sensible thing to do in a country where graduates are likely to be unemployed even after acquiring additional degrees, is a different question altogether[10]. More significantly, it is difficult to imagine that a university graduate would not find a job in the 1970s. Yet, an overwhelming majority of those who took the loans did not pay back. This suggests that employment or lack of it is not really the main factor in repayment, but something else.

Why Is Student Loan Necessary?

From what President Tinubu and the lawmakers have said, the impression is that the student loan scheme is a social intervention programme designed for the sole reason of granting access to higher education to students from poor homes. Viewed in historical and global context, this would be a strange reason indeed. The world over, conversations about student loans have always taken place in the context of ‘cost-sharing,’ which according to Bruce Johnstone is a euphemism for the introduction of tuition[11].

In June 1991, a number of education specialists from nine English-speaking African countries gathered in Nairobi, Kenya to share experience on student loans in their respective countries. They came together under the auspices of the UNESCO-backed International Institute for Education Planning (IIEP)[12]. The conference observed that the policies of awarding grants, bursaries and allowances that were introduced in the early years of independence to develop the indigenous manpower base of African countries were no longer sustainable in the face of sky-rocketing enrolment and severe financial pressures, which threatened the quality of higher education. This was the basis for the introduction of tuition and other fees as well as student loans in many of the countries, and based on the principle of “cost-sharing”.

However, the argument for cost-sharing in higher education has been led over the years by economists. Their main contention is that higher education is a “profitable private investment.” Therefore, in the face of dwindling government revenue, it is reasonable to expect students and graduates to contribute towards the cost of higher education by repaying loans after they have left the universities[13].

The general principle is that those who can pay should be made to pay, and those who cannot pay should be assisted to pay. A system that guarantees free tuition for everyone, regardless of their financial status, gives disproportionate advantage to those who can pay but are not required to. The consensus is that where additional taxes are difficult to impose, where taxes tend to be regressive, then failure to charge, at least, a moderate tuition fee leaves behind revenue that could otherwise have improved higher education quality or provided financial assistance in form of means-tested grants and loan subsidies to enhance accessibility to those that are extremely needy.

In a 1988 report on education in Sub-Saharan Africa, the World Bank recommended increased cost-sharing in higher education as a solution to the problem of increasingly underfunded and overcrowded universities in developing countries. It therefore advocated student loans or other forms of credit as a means of assisting students to pay tuition or other charges and costs. Hence, countries that had traditionally pursued a policy of subsidised or free higher education, including countries like China, Vietnam, India, as well as countries in Latin America and Africa started to introduce some kind of fees and charges[14].

The fact that the World Bank had championed the policy of cost-sharing, especially as part of the Structural Adjustment Programme (SAP) in the 1980sled its critics to regard it as a neo-liberal prescription which tends to favour reduced public expenditure and increased reliance on user fees[15]. This is probably the reason that the Academic Staff Union of Universities (ASUU) has opposed both the idea of tuition or even of the student loan. However, the challenge of poor funding of higher education and the resultant poor quality transcends ideological boundaries. Even Russia, and other former Soviet Union countries as well as other countries of Eastern Europe that had historically enjoyed constitutional guarantees on free higher education are in a dilemma and are looking for ways to introduce tuition to supplement inadequate public revenues. Johnstone reported that while Russia continues to guarantee free higher education, it has since 1992introduced a kind of dual-track admission system. It admits a number of students on merit into a limited number of “government places”. Students in this category are not required to pay tuition. But those who are unable to meet the cut-off marks, nearly half of the students by 2002, have to pay tuition, which contributed to more than a quarter of the university revenues[16].

Beyond the ideological arguments therefore, the question remains how to fund the universities effectively when rapid increase in enrolment coincides with declining allocation from government and rise in per-student cost. In May 2023, the Vice Chancellor of the University of Benin, Professor Lilian Salami, while advocating for greater parents’ involvement in cost-sharing noted that while it costs N3 million per year to train a medical student, the students only pay N240,000 in six years or N40, 000 in a session[17].

Funding system of the universities does not however align with this kind of realistic per-student costing. Official reports show that in a twelve-year period (2011-2023), more than 90 percent of budgetary allocations to the universities consistently goes to personnel cost. In other words, funding has followed staff recruitments rather than the number of students or the requirements of their individual courses. Professor Salami also reported that although her university receives a monthly overhead allocation of N11 million, the university spends N77 million on electricity alone. This is consistent with available records which shows that after paying salaries, the federal universities are left with between 0.4-1.0 percent of their allocation for overhead, which, apart from electricity, also includes laboratory re-agents and other study activities.

It should be noted therefore that the argument for tuition payment or some other forms of cost-sharing is not an argument for reduced government spending on higher education. Like Wellen has noted, tuition does not necessarily offset reduced transfers from government[18]. This is why per-student costing remains the most effective way to plan university funding because it also allows for adjustments to reflect fluctuation in operating cost on a year-to-year basis, a realistic assessment of the funding gaps, as well as multiple strategies to fill the gaps. The overwhelming focus of the current funding system on personnel cost is wrong-headed and ruinous.

Even with tuition payment, Nigerian universities will still need to open up and pursue other sources of funding. After all, even countries with long history of tuition fees still strive to generate incomes through other means like grants and contracts, business ventures, sale or lease of university facilities, and donations from alumni, friends and corporations. However, just like tuition alone does not guarantee effective funding of the university, these other sources alone will also not be sufficient. But, like Johnston noted, the advantage that tuition has over these other income-generating activities and charitable sources is that it does not lead to new cost or divert faculty from their core teaching functions[19].

Nevertheless, it is understandable why an elected government would be reluctant to announce tuition payment. But introducing student loan, an important tuition off-setting transfer, without establishing how this would lead to increased revenue for the universities will suggest either that the government is disguising its real intentions or it is introducing the loan for other reasons not related to education.

The sudden increase in charges and levies that was witnessed as the earlier commencement date of the loan scheme approached last year was the institutions’ way of side-tracking the ban on tuition. It therefore appears that the only options left for government is either to officially lift the ban on tuition, which it can cap for federal institutions, or allow the kind of escalation of discretionary levies that was witnessed last year, which leaves the students at the mercy of the institutions.

How to Make Student Loan Work Better

The main conclusion of the 1991 IIEP conference in Nairobi was that student loans have an important part to play in finding new sources of finance for higher education. The forum identified six factors that could aid the success of student loan schemes: sound institutional structure for management of the loans; sound financial management that protects against depreciation of the capital base; sound legal framework to ensure that loan recovery is legally enforceable; effective mechanism for selecting recipients based on financial need or manpower priorities; effective machinery for loan recovery and; publicity campaign to promote understanding of its principles and the obligations to repay[20].

As noted earlier, the 2024 Act has minimised the risk of political interference contained in the earlier Act that left the control with the CBN. This should strengthen the management and administration of the fund. The financial management model is also likely to protect against currency volatility. However, there is nothing in the new law that guarantees better recovery than in the earlier attempts. Even if the legal framework for recovery is strong enough, actual enforcement could still be problematic. In the end, the financial, social and political cost of collection may overwhelm whatever benefits the government set out to derive from the scheme.

In addition, unlike the 2023 Act, the 2024 law does not discriminate based on social-economic background. This may turn out to be a major drawback. A system that is free for all creates a situation whereby those who can afford to pay are still the ones that benefit from the loan, especially when they think there is a chance to get away with repayments. The earlier Act that allowed only those whose family income does not exceed N500,000 per annum to apply excluded nearly everyone. But making the loan available to everyone, whether they are in need or not, is regressive and potentially disadvantages those who really need the loans, especially when too many people are applying to the same limited pot of fund.

As Johnston has noted, establishing “financial need” is very difficult to ascertain in countries where private sector incomes may not be declared or may be under-declared. This is true in our case. Nevertheless, some kind of discriminatory standard is necessary to ensure that loans are targeted at those who really need it and to ensure that repayment is tailored to the needs and preferences of individual borrowers. Countries with longer and successful history of student loans provide options to students based on their needs[21]. Without some kind of means-testing instruments, it is hard to see how we can do this. Moreover, the law gives the board discretionary power to determine or waive the terms of repayment. If this is not based on pre-defined parameters, it would only provide loopholes that allows privileged borrowers to get easy reprieve.

In an initiative such as this, communication will be key. At the moment, not much appears to be happening in this regard. Again, the implication is that only those who have access to information are likely to be the greater beneficiaries. Some communities have strong cultural aversion to debts. People from such communities are not likely to be enthusiastic about obtaining a loan for fear of what could be the consequences if they are not able to pay. A lot more work needs to be done therefore to enlighten such people about the opportunity and what the loan actually means.

Similarly, socio-cultural aversion to loans by women in some parts of the country may marginalise them from benefitting from the loan if deliberate affirmative tools are not built into the award and repayment system. Although the new Act provides for equitable distribution across the six geo-political zones, it fails to make special provision along gender and disability lines. At the policy level, some kind of positive discrimination provisions need to be introduced. A system that applies the same rule to everyone overlooks those who ab initio are disadvantaged.

Loan Does Not Work Alone

As noted earlier, every policy about student loan is always driven by the need for cost-sharing to ensure better funding for higher institutions. Therefore, it is difficult to find a single instance where student loans are introduced without a clear link to improving funding of higher education whether through moderate tuition combined with other charges, tuition only, or other charges only. Loan is essentially a cost-offsetting instrument. In providing funding support to students therefore, loans are usually combined with other instruments such as means-tested grants, and merit-based scholarship to ensure that support is targeted at those who need it most.

- Merit Based Funding: The Dual-Track Admission (DTA)

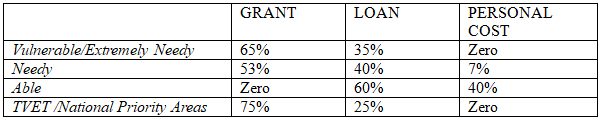

DTA provides a way to side-track the political and social cost of introducing tuition, like in the case of Russia mentioned earlier. The DTA system admits students through two tracks. The first track is for National Merit Students (NMS) who are admitted through amerit-based system. Students who are able to meet a pre-determined cut-off pointor those who are top of the best within a pre-determined number of candidates are admitted this way. The NMS students will not pay tuition fees, but they may obtain loans for other expenses[22]. The second track is for Private Entry Students (PES). This category of students may have chosen not to apply through the merit-based system or may have failed to meet the cut-off marks for government funding. However, they may also apply for the loan to pay both tuition and other expenses. - Needs-Based Funding

The general principle of needs-based funding is to provide discriminatory support to students based on parameters that primarily consider the social standard or condition of the students or their parents. A means-testing instrument is developed which establishes the economic condition/status of the student to ensure that everyone is able to pay according to their ability and needs.

A modification of this tool would include other affirmative-action criteria (gender, disability, talented athlete) or consideration for national priority area such as Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) or agriculture-related courses. The table below outlines a possible framework for this funding approach for all levels of higher education. Personal cost stands for percentage of instructional cost that would be borne by the students themselves.

Summary of Observations and Recommendations

- Student loan is a cost-offsetting instrument. It should therefore be tied to the need to increase funding to higher institutions rather than for merely expanding access. Expanding access into without expanding funding for the higher institutions undercuts their capacity to deliver quality education.

- Loan or tuition does not substitute for government allocation. But funding system should be based on per-student costing which should also reflect changes in operating cost on annual basis. Using per-student costing approach will ensure that our higher institutions have adequate funding deliver quality education and greater value to the students and the country.

- Tuition or other fees need to be formalised and standardised to minimise discretionary charges which leave the students at the mercy of the institutions and to increase the pool of funding available to the institutions.

- The Student Loans Act, 2024 is still replete with several weaknesses that opens the scheme to abuse both at the levels of loan award and recovery. These weaknesses should be addressed at the policy implementation level.

- Making the loan available to everyone potentially disadvantages those who actually need it. Some kind of means-testing instruments need to be developed to ensure that loans are targeted at those who need it most and recovery is also tailored to their realities.

- Loans should be combined with merit and need-based grants to make it more effective and equitable.

- A deliberate policy of positive discrimination needs to be adopted to reflect the needs of gender, disability and the priorities of the country.

- The scheme needs to be driven by a robust communication strategy to ensure that those who are culturally averse to loans are not excluded and to drive messages that could aid recovery.

*Mallam Bolaji Abdullahi, former minister of youth development and sports, is a policy practitioner and education reform enthusiast.

Link to Download File

https://agorapolicy.org/files/Student_Loan_Scheme.pdf

Photo Credit: Opening image: Sourced from Meta AI

Footnotes

[1]Part III, Section 17 (C), indicated that the Fund is allowed to receive fund from “repayment and interest on any loan granted by the Fund”

2] For detailed history of student loans in several English-speaking African countries, see Maureen Woodhall, Student Loans in Higher Education, Report of an International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP), UNESCO, Paris, 1991.

3] See Annexure VI – Nigeria, ibid.

[4] Ibid

[5] Annexure A- Nigeria, Opp cit.

[6] In fact, section 6 (1c) of the decree and Section 17 (1c) of the Act are almost identical in their wordings.

[7] Students Loans Board Decree No. 25, 1972, Sections 9 (1b) and 12 (2a and b).

[8]Students Loan (Access to Higher Education Repeal and Re-enactment) Act, 2024, Section 3(b).

[9] Annexure A- Nigeria, op cit. pg. 66.

[10]Citing a Stears Business data, thecable.ng reported that 40 percent first degree holders, 28 percent of those with Masters degree and 17 percent of those with Doctorates are unemployed in Nigeria in 2020. See https://www.thecable.ng/nigerians-are-formally-educated-but-informally-employed.

[11] Johnstone (2003). Cost Sharing in Higher Education: Tuition, Financial Assistance, and Accessibility in Comparative Perspective. Czech Sociological Review, June 2003, Vol. 39 No.3 pp.351-374. See also, Woodhall, op cit., Wellen R. (2004), Williams P. (1974); World Bank (1988).

[12] Countries represented includes Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe. See Woodhall, op cit.

[13]Johnstone (2003).Op cit.

[14]Johnstone (2003).Op cit.

[15] Wellen (2004). The Tuition Dilemma and the Politics of “Mass” Higher Education. The Canadian Journal of Higher Education. Vol. XXXIV. No. 1. Pages 47-81.

[16]Johnstone (2003).Op. cit.

[17]Bodunrin (2023). FG Can No Longer Fund Tertiary Education. https://tribuneonlineng.com/fg-can-no-longer-fund-tertiary-education/

[18]Wellen (2004). Op cit.

[19]Johnstone (2003).Op cit.

[20]Woodhall, op cit.

[21]These could be Income Contingent Repayment (ICR), Income Based Repayment (IBR) or Income Sensitive Repayment (ISR), or Pay as You Earn (PAYE) etc.

[22] However, for each NMS, the government will still pay the full cost of tuition to the university.