By Douglas Okonko | Nigeria is currently facing diverse threats to its national security. These threats have serious implications for social, economic, and political development. According to a report published by Agora Policy titled, Understanding and Tackling Insecurity in Nigeria, “The nation is presently facing generalised insecurity with hardly any of its six geo-political zones spared from one form of insecurity or the other…” The country, the report said, “is practically under the gun on all fronts”.[1] Why is Nigeria under the gun on all fronts? There are several answers to this question, but one of them is that Nigeria’s borderlines are under-protected.

According to the Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS), there are 80 supervised entry ports, compared to 1490 known illegal entry routes[2]. The porous nature of Nigeria’s borders should get policy makers seriously worried. Through Sokoto, militia groups from Niger have been crossing the border into Nigeria unrestricted. Ambazonia rebels seeking safety from the government have also crossed the Nigerian-Cameroon border into border towns in Taraba State and Cross River State. There are occasions terrorist combatants and supplies have moved unhindered through the Nigerian-Chad and Nigerian-Cameroon borders.3 In the Southwest and Northeast regions, smuggling of contraband goods from Benin and Togo via Lagos, Kwara, Ogun, and Niger states persists.

Fig 1: Map showing Nigeria’s borders with neighbouring countries

The current state of our borderlines enables insecurity. As such, finding a durable solution is of utmost priority. This does not mean that efficient border security will resolve every security problem. Rather, it means that securing our borders by establishing a dedicated border force is a critical step towards ensuring national security. Here is why.

Rationales for a Dedicated Force

There are several reasons why we need a dedicated border force, but four of them stand out.

First, as stated above, Nigeria is currently battling generalised insecurity: none of its six geo-political zones is spared from insecurity. Although in decline, the impact of terrorist activities can still be observed in the Northeast4. ISWAP and Boko Haram continue to criss-cross Nigeria’s borders with Chad and Niger to perpetuate violence. According to Global Terrorism Index, 120 incidents of terrorism and 385 deaths were recorded in Nigeria in 2022.5Significantly, the activities of criminal gangs (bandits) in the North West and North Central regions caused more civilian deaths in 2021 than Boko Haram and ISWAP. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) also reported that, armed bandits killed more than 2,600 civilians in 2021.6The prevalence of insecurity in the North West and North Central zones could be linked to poorly policed borders. These porous borders have encouraged the spread of terrorist activities and weapons from Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger. South West and South South are equally burdened by issues of insecurity.

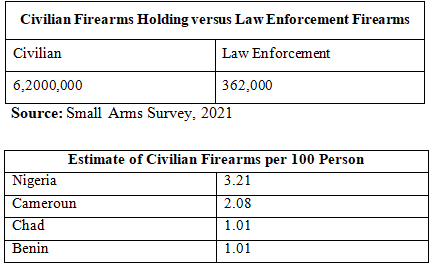

Secondly, the porous nature of Nigeria’s borders has accentuated the influx of arms into the country over the past two decades. This in turn has heightened the wave of terrorism, banditry, kidnapping, and other violent crimes. According to a report released by Small Arms Survey (SAS), civilians in Nigeria possessed more firearms than personnel of law enforcement agencies.7 SAS also reported that out of 100 persons, 3.21 carry firearms mostly smuggled from Sahel trafficking networks. It is also estimated that of the 500 million illegal weapons circulating in West Africa, 70% are domiciled in Nigeria.8

Source: https://www.smallarmssurvey.org/database/global-firearms-holdings

Relatedly, Nigeria’s porous borders and weak border security mechanisms pose a serious challenge to the fight against trafficking in illicit drugs. Unchecked entrance of illicit substances threatens public health as well as enhances criminal tendencies. The UNODC reports that14.3 million (14.4%) Nigerians aged between 15 and 64 years use illicit drugs.

The third rationale is that the current structure for securing our borders is fragmented and suboptimal. Nigeria runs a multi-agency border management arrangement spearheaded by the Nigerian Custom Service (NCS) and the Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS). Among other immigration and custom-related duties, these two agencies face the daunting task of securing West Africa’s third longest land borderline spanning 4045 km. Significantly, these agencies are under the supervision of different ministries, and they operate independently of each other. The NCS is under the Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning while the NIS is supervised by the Ministry of Interior. Although both agencies have a component of border security as part of their operations, the revenue-generating departments take precedence. This is at the expense of border patrol and national security. It gravely underscores the danger of diffused mandates for government agencies.

Lastly, the economic cost of a largely unprotected border is enormous. Nigeria’s porous borders have created an enabling environment for smuggling. Nigeria’s total revenue loss to smuggling activities is not clear but its impact on the economy can be felt. Millions of dollars that would have been generated through formal taxation have been lost to smuggling. According to a report by Chatham House, Oil theft in Nigeria is costing the country up to US$1 billion per month in lost revenues.9In 2010, 80% of Benin Republic’s domestic fuel consumption was smuggled from Nigeria, ata value in excess of US$863 million.10 This shows the level vulnerability of Nigeria’s borders. Smuggling has also distorted market prices and created unfair competition with locally produced goods. It has also led to the collapse of local manufacturing, loss of jobs and high rate of unemployment.

Recommendations for Operationalising the Border Force

Without a doubt, Nigeria needs a dedicated border force patterned after the United States Border Patrol (USBP), the Australian Border Force, the Border Security Agency of Malaysia, and Canada Border Services Agency. The impact of these dedicated agencies is well documented. For instance, the U.S. Border Patrol (USBP) apprehended 1,148,000 illegal migrants in 2019 and seized more than 112,000 pounds of assorted illegal drugs in 2022.11Securing the home from the gates is becoming a favoured tactic amongst nation-states. Nigeria can, and should align, with this increasingly approach with the creation of the dedicated border force, which should be backed by law. A bill (preferably an executive bill) thus needs to be initiated to authorise the creation and set out the operational framework of the force with the sole mandate of guarding Nigeria’s borders. The proposed force should be under the Federal Ministry of Interior.

The border force will require smart recruitment and elite training beyond what presently obtains. For example, the NIS has 25,303 staff members, out of which an undisclosed number of officers is under the command of the Directorate of Border Security. It is also not clear how many officers are under the Rural Border Patrol Operation (RBPO) of the NCS. In comparison, the U.S employs approximately 5, 000 border patrol agents to patrol 388 miles (624 km) of its southwestern border alone. To have comparable number of personnel per kilometre, Nigeria therefore will need to employ 32,395 border patrol agents for its 4, 043kmland borders. The point here is that the proposed border force must have adequate personnel for the demand of its mandate.

Although numerical strength plays a key role in security, a skilled and specialized number is better. Combating transnational crime will require the expertise of different security agencies. Before fresh recruitments into the suggested border force are implemented, the initial pool of officers should be drawn from existing security agencies to minimise cost and ensure the recruitment of officers with specific expertise and field experiences. Officers should be drafted from the National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA), Defence Intelligence Agency(DIA), National Intelligence Agency (NIA), Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), Nigerian Custom Service (NCS), Nigerian Immigration Service (NIS), the Nigerian Police (NP) and the Nigerian Security and Civil Defence Corp (NSCDC).

The inter-agency composition of the Border Force will enable the establishment of a comprehensive operational picture in specific areas of trans-border crimes including drugs, arms and human trafficking, oil theft, piracy, and money laundering. Before take-off, however, there is the need for a plan to fully integrate and socialise the staff drafted from different agencies and presumably from different organisational cultures and orientations. This integrated approach will encourage a single chain of command and control. Qualified personnel should be trained by experts in the field of border patrol. Also, exchange programmes with countries that have successfully institutionalised a dedicated border force should be embraced. It is expected that the training and exchange programmes will build a strong and resilient border force with the required technical, tactical, and operational skills to operate and adapt to changing conditions.

Another key area is modus operandi for deploying officers of the force. Nigeria is bordered to the north by Niger, to the east by Chad and Cameroon, to the west by Benin, and the South by the Gulf of Guinea of the Atlantic Ocean. These borders vary in distance, prevalent crimes, and security threat levels. As such, the number of personnel deployed and the kind of personnel deployed (in terms of training and primary skill set) should be determined by these three factors (distance, prevalent crime, and security threat level). To maintain the high standard, professionalism, and integrity, oversight and accountability measures should be implemented to ensure that officers fully understand and abide by the operational guidelines of the force.

Securing Nigeria’s 4, 043km border requires more than just physical deployment—the force must leverage on modern technology to achieve its goals. Even for a dedicated border force, it is impossible to cover every inch of Nigeria’s borders. Advancement in modern ICT has enabled the incorporation of technology into border security possible. Technology can be used to detect, identify, classify and communicate threats in “hard-to-reach terrains”. Since 2017, the US Customs and Border Patrol received more than $700 million in funding for border technology.12Even though the proposed dedicated border force may find it hard to attract such a huge investment in the interim, it still needs substantial investment in modern technology for it to be effective. Before the purchase and deployment of technology, the border force should develop a clear strategy and plan that covers its technological needs, and describes the need and appropriate area of deployment. Officers should be trained on how to best use acquired equipment or facility. Acquired technology should be regularly upgraded and monitored to avoid compromise. Some of the available border technology that could be used include unmanned drones, relocatable towers, sensors, and mobile land-based radar trucks.

Advancement in technology should not take away the place of infrastructure. Border infrastructure includes not just fencing and other physical barriers, but also roads that provide access to the borders and areas along the borders for quick response. Sector stations and other operating bases of the border force should be situated at or close to key illegal entry “hotspots” to accelerate response time. Preferably, these stations and bases should be movable in anticipation of route diversion by criminals.

Conclusion

Porous borders have been identified as a major driver of insecurity in Nigeria and if allowed to linger will cause further damage to human security and further stifle socio-economic development. Nigeria’s weak borders call for the establishment of a dedicated border force with the needed legal backing, expertise, technology, training, infrastructure, and intelligence to detect, identify, classify, prioritise, and mitigate security threats along its expansive borders.

*Okonko is a Research Officer at Agora Policy

Foototes

[1] Agora Policy, “Understanding and Tackling Insecurity in Nigeria”, Agora Policy Report, No.2, Nov, 2022, p,8

[2] AKin Akibola, “Immigration decries inability to effectively man borderlines”, Channels Television, May 24 2022,https://www.channelstv.com/2022/05/24/immigration-decriesinability-to-effectively-man-borderlines-1490-illegal-entry-points/, Accessed 22 March, 2023.

[3] Agora Policy, “Understanding and Tackling Insecurity in Nigeria

[4] The impact of terrorism continues to decline in Nigeria; with total deaths falling by 23 per cent, decreasing from 497 in 2021 to 385 in 2022. The number of terrorist attacks in Nigeria also fell considerably, with 120 incidents recorded in 2022 compared to 214 in 2021. This is the lowest number of terror attacks and deaths since 2011.

[5]Global Terrorism Index 2022, “Measuring the Impact of Terrorism”file:///C:/Users/HP/Downloads/GTI-2022-web_110522-1.pdf, Accessed, March 30, 2023.

[6] Aaron Karp“Estimating Global Civilian-held Firearms Numbers”, Small Arms Survey, Briefing Paper, 2018 p,10

[7]Tribune Online, “Insecurity: 70 percent of illegal weapons in West Africa domiciled in Nigeria”, April 19, 2021, https://tribuneonlineng.com/insecurity-70-per-cent-of-illegal-weapons-in-west-africa-domiciled-in-nigeria-%E2%80%95-unrec/, Accessed 21, March, 2023.

[8]Royal Institute of International Affairs (2013). Maritime Security in the Gulf of Guinea. Report of the conference held at Chatham House, London, 6 December 2012. Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Africa/0312confreport_mariti mesecurity.pdf

[9]UNODC, “Transnational Organized Crime in West Africa: A Threat Assessment. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime”.https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-andanalysis/tocta/West_Africa_TOCTA_2013_EN.pdf,

[10]John Davis, “Border Crisis: CPB’s Reponse”, https://www.cbp.gov/frontline/border-crisis-cbp-sresponse, Accessed, 22 March, 2023.

[12]Homeland Security, “CBP has Improved Southwest Border Technology”, February 23, 2021, https://www.oig.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/2021-02/OIG-21-21-Feb21.pdf, p.2