By Bolaji Abdullahi

Over the last two decades, the global focus on education had been on bringing every child to school. This was in line with the goals of Education for All (EFA) and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). Despite the reported 10 million children out of school, Nigeria has made remarkable progress in pursuit of universal basic education and has more children attending schools today than at any other time in the country’s history1.

However, the growing crisis of youth unemployment and mass poverty means that simply achieving universal literacy and expanding access are no longer enough. Nigeria must rebuild its education system to deliberately address some of the most pressing social and economic challenges the country faces today and in the near future.

The new administration must therefore communicate, very early, the desire to place the education sector at the center of its plan to create a job-led economic growth, tackle youth unemployment and reduce poverty. Consequently, it must declare its commitment to pursue a holistic reform of the education system to make it more functional and relevant to the needs of the nation’s economy.

Education should provide the pathway to a prosperous future for the individual and the nation. The longer an individual stays in school to acquire knowledge and skills, the higher should be their chances for social mobility and freedom from poverty. An education system that is no longer able to deliver on the promise of a better future has failed and needs to be rebuilt.

This paper will highlight key misalignments in Nigeria’s education system and discuss possible approaches to creating a more functional education system through restructuring and main streaming of technical and vocational education in the country.

The 6-3-3-4 System and A Promise Not Fulfilled

The 6-3-3-4 system was introduced as a departure from the colonial education legacy which had been designed to produce white collar workers and to replace it with an education system that is both pragmatic and functional. The new education system would be flexible, providing multiple points of entry and exit; it would inculcate foundational practical skills that would prepare young Nigerians for the world of work much early; and it would provide opportunities for continuing professional advancement. The end goal was to produce a new generation of educated Nigerians who would not be disdainful of vocational work and would therefore be more suited to the nation’s emerging economy that was beginning to focus more on production and industrialisation.

Although education experts had started to have conversations around building this kind of education system in the years immediately following independence in 1960, the collapse of global oil prices in the early 1980s, which almost crippled Nigeria’s oil-dependent economy must have made it even more imperative. The plan to build a more diversified economy and make the country less vulnerable to future volatility in the international oil market meant that the nation would require workers with a mentality of self-reliance and the ability to use their hands as well as their brains.

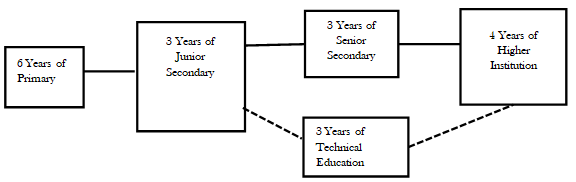

Under this system, all students would complete six years of foundational primary education. This would be followed by three years of junior secondary, which delivers general curriculum alongside introductory technology and pre-vocational subjects. This first three years would also provide the first terminal point. From here, students can exit to informal apprenticeship scheme, or proceed either to a technical college or a senior secondary school for another three years. While those who proceed to senior secondary schools are expected to go on to a higher institution for another four years, those who go to technical colleges are expected to have acquired employable technical/vocational skills, but the pathway remained open to them for higher education as well. Figure 1 below shows the 6-3-3-4 as planned:

Figure 1: 6-3-3-4 in theory

The planners of 6-3-3-4 envisaged that about 60% of students completing the first three years of junior secondary would transit to senior secondary with strong academic focus. Another 30% would proceed to technical colleges, and the remaining 10% would exit to trade and apprenticeship programmes2. This has not been the case. Instead, the education system has remained largely one-dimensional in practice as all students are herded into the more theoretically-oriented senior secondary schools, therefore rendering the national junior secondary terminal examination superfluous. Even a switch to a 9-3-4 system, which made the junior secondary part of compulsory basic education and the minimum educational qualification in the country, did not bring about any substantial change. After four decades, it is safe to conclude that the system has not delivered on one of its core promises.

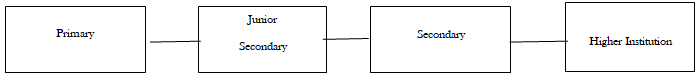

Under the 6-3-3-4, technical colleges were meant to anchor Nigeria’s step-change towards more functional education. For sundry reasons, which have been well documented in the rich literature on the issue, this did not happen. While the number of secondary schools, both private and public, has grown exponentially since the system was introduced, the total number of accredited technical colleges for the whole country is a paltry 1273. The technical colleges are usually sparsely attended, having been inadvertently framed as ‘refugee camps’ for less intelligent children who would end up as artisans and therefore have no prospect for social mobility. On the other hand, secondary schools appear to exist only to prepare candidates for SSEs and the matriculation examinations into higher institutions, especially the universities. In reality, 6-3-3-4 has been operated as shown in Figure 2 below:

Figure 2: 6-3-3-4 in Practice

At the time the 6-3-3-4 was being introduced in 1983, there were only 104, 774 students enrolled in all the 19 universities in the country4. Currently, there are 170 federal, state and private universities in Nigeria with a total enrolment of close to two million students. Yet, even with the polytechnics and colleges of educations added, only about 25% of eligible applicants are able to gain admission in a given year5.

Reports that three-quarter of candidates who qualify for admission into universities each year cannot find a place has been used by the government to justify the establishment of more universities even in the face of daunting challenges of funding, governance and overall quality. However, expanding opportunities for young people to acquire degrees without a corresponding expansion to the relevant job opportunities can only increase the army of frustrated youths armed with certificates of entitlement. Available reports estimate that there are about 2.9 million unemployed graduates in Nigeria6.

People Looking for Jobs Versus Jobs Looking for People

In the last decade, Nigeria has consistently released between 500, 000 and 600, 000 graduates into the labour market every year. Multiple reports indicate that at least half of these graduates would not be able to find formal jobs. Unable to get a job, many usually return for postgraduate degrees and some even up to doctorate level, yet these additional degrees hardly improve their prospects of getting employed. Citing a Stears Business data, TheCable (an online newspaper) reported that 40% of first-degree holders, 28% of those with Masters degree and 17% percent of those with doctorates are unemployed in Nigeria7. With Nigeria rated as the third country in the world with the highest number of unemployed people below 35 years, the nation’s much touted demographic advantage is fast turning to an albatross or, as it has been ominously framed, a ticking time-bomb.

A 2011 Job Creation Committee of the Federal Government identified five core sectors described as the growth drivers for the Nigerian economy. These include agriculture, construction, ICT, the creative industry (music, films, fashion, photography) and sports. These sectors are also thought to hold the greatest prospects in Nigeria’s quest to build a job-led economy. It is indeed noteworthy that most of the jobs available in these sectors do not require a university degree. Yet, many of these sectors still suffer from a dearth of quality skilled workers. A 2022 Survey by Equinix reported that 58% of Information Technology leaders in Nigeria consider shortage of personnel with technology skills as a major threat to their business8. In his meeting with former President Muhammadu Buhari in 2015, the board chairman of Julius Berger Group, arguably Nigeria’s biggest construction company, lamented the dearth of “competent construction workers and artisans” in the country, which he said has led many construction firms to import skilled workers from abroad9. It is also a well known fact that Nigeria builders, fashion designers and restauranters prefer to employ their key staff from even neighbouring countries because of the quality of the skills and their attention to details.

Urgent Need to Mainstream Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

In recent years, this has been a very popular subject among Nigeria’s educationists, policy actors and even multilateral agencies like the World Bank10. The body responsible for maintaining standards in technical and vocational education in the country is the National Board for Technical Education (NBTE), which also regulates the National Skills Qualifications standards under the Federal Ministry of Education. Two other government agencies play critical roles in this area. The first is the Industrial Training Fund (ITF), an agency of the Ministry of Industries. It coordinates and supports apprenticeship training. In January this year, the ITF launched a

National Apprenticeship Training System, which it says will “ensure a structured approach to skills acquisition and certification” and enrich the system “with international certification for the various trades11.” The other is the National Directorate of Employment, (NDE) which operates under the Ministry of Labour and Productivity and has run an open apprenticeship scheme since 1987.

A cursory review of the approaches and activities of some of the key actors would reveal some fundamental problems. Such problems include the following:

- Although the various agencies proclaim a common mandate to enhance technical/vocational skills, they operate almost wholly independent of one another.

- Despite growing interest in TVET education in the country, there is lack of conceptual and operational clarity on how it should be delivered and who should be playing what role. For example, ITF, a funding agency, has in recent times veered into execution and even sets up training facilities.

- There is little or no evidence that employers play any significant role in designing the contents of curriculum or participate in delivering trainings at any level.

- Although the formal vocational trainings are certificated, there is no assessment or certification for apprenticeship programmes.

- There are no clearly defined targets, therefore it is difficult to measure performance based on impacts.

Lessons from Germany and the United Kingdom

The German vocational training programme is based largely on the Ausbildung or Apprenticeship. Although there are five forms of vocational training in the German system, which cater to different level of professional and educational entry-level training and retraining, the dominant form is the Dual Vocational Training (DVT), which accounts for 70% of vocational training and apprenticeship in the country. Under the DVT, a trainee attends a formal vocational school (Berufsschule) for one or two days in the week and attends in-company training or apprenticeship for the remaining days. For some courses, the school-based training is held in block for a few weeks, then the trainee returns to the company providing the training. During the in-company training, or apprenticeship, the trainee gets paid. The entry level is usually 12thgrade or senior secondary and the minimum enrollment age is 17. Assessment is carried out by a combination of midterm and final examination in the school, as well as the work-place assessment. The duration is usually about three years.

Another major form is the school-based vocational training, which takes place full time at state-owned or private vocational academies or colleges and lasts for one to three years. Students are not paid, and those attending the private institutions may pay school fees. But they are entitled to financial support under the Federal Training Assistance Act. 12

In the United Kingdom, technical and vocational education training is largely employer-centered. The employers play a key role in designing and delivering the training as well as in assessment. Training is delivered through public and private colleges, and work places, and includes a wide range of training providers such as 6th form colleges, employers, further educational colleges, specialist providers, and universities. Although training usually starts at age 16, the focus is on providing flexible lifelong learning that allows trainees to move seamlessly at different times between work and school throughout their career.

Apprenticeship is also a major system for TVET education in the UK. It delivers work-based training alongside college-based training, which also allows the trainee to work towards a range of qualifications including certificates, diplomas, foundational degrees, and NVQs, which are convertible to educational qualifications as pathways to employment or further studies and trainings up to post-graduate levels. TVET in the UK is largely demand-driven. Therefore, the standards and frameworks are usually designed by the employers, who ensure that training outcomes meet industry standards and are responsive to development in the industry. Although government provides subsidies and loans to fee-paying students, employers contribute apprenticeship levy of 0.5% of their annual wage bill if the wage bill is up to 3 million pounds. Apprentices have full employment status and are paid wages13.

Convertibility of qualifications across the various pathways of academic, technical and apprenticeship also ensures parity of esteem between them. For example, Level 3 apprenticeship qualification is equivalent of T-Level and A Level qualifications T-level Distinction* is worth the same as 3 A Levels at A*. Level 4 apprenticeship is same as first year of undergraduate or Higher National Certificate, while Level 5 apprenticeship is equivalent to a foundation degree or Higher National Diploma (HND).

TVET in the UK is governed by several agencies which include the employers, the training providers, the qualifications regulator, the funding agency, the inspection agency, national skills agency etc. in a dense network of relationships. However, the remit of each agency is clearly defined and each agency understands its role as part of a system.

Towards a New Framework for TVET in Nigeria

The examples of the two countries above make it clear what Nigeria needs to do if it must build an educational system that is able to deliver much needed technical and vocational skills. Some are outlined below:

- TVET must be integrated into the heart of the educational system rather than as a poor alternative for those who are less academic-minded.

- TVET policy and governance framework must be clearly articulated and the role of every actor clearly defined.

- Qualifications must be prestigious enough to attract up-takers and must be convertible across pathways allowing for employment and further education/training.

- Training must be of high quality and meet employers’ needs. Therefore, the industries and businesses must be incentivized and allowed to play a lead role in designing the framework and standards for training along occupational lines.

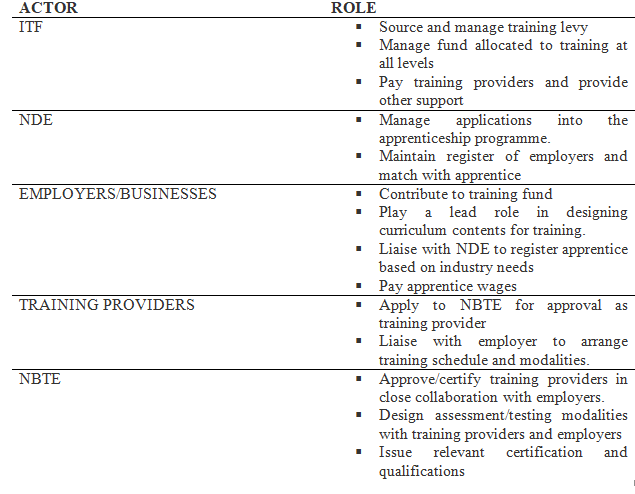

- Building a robust, dynamic and market-oriented TVET education requires many actors operating at different levels. One of the factors that have held back performance in the past is poor inter-agency collaboration and lack of clarity about who should play what role in a system that requires constant engagement and collaboration. A major step forward would be one that finds a role for all stakeholders in a governance framework that allows for close interaction as well as relative autonomy. The table below outlines some of the actors and the possible roles they can play in the new system.

TABLE 1:Proposed structure for management of apprenticeship programme.

Imperative of Evolving a New Education System

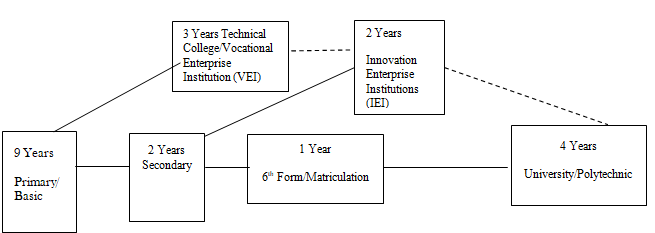

The new education system provides three inter-connected pathways after the compulsory nine years of basic education. The first pathway takes a child through two years of secondary (senior secondary) and additional one year for matriculation to the university or polytechnic. The second pathway takes a child completing basic education to the Technical College or the Vocational Enterprise Institute (VEI) for one, two, or three years. The student completing the 3rd year of the VEI may then wish to proceed to the Innovation Enterprise Institute (IEI) for advanced level skills training for two years. This then qualifies her to enter into a university/polytechnic, with some of the IEI credit portable towards earning a degree or diploma. The third pathway is for those completing two years of secondary, but do not wish to go to the university directly. They may proceed to the (IEI) for two years, and may proceed to university or polytechnic afterwards. This new system is illustrated in Figure 3 below:

Figure 3: A New Education Structure

Reinvigorating Vocational Enterprise Institutions and Innovations Enterprise Institutions

Vocational Enterprise Institutions (VEIs) and Innovation Enterprise Institutions (IEIs) are privately owned institutions for the provision of technical and vocational training in Nigeria. They are accredited and regulated by the National Board for Technical Education (NBTE) to deliver vocational, technical, technological education and training at the post-basic education (VEIs) and post-secondary levels (IEIs). At the moment, there are close to 300 of such institutions accredited by NBTE across the country, offering a broad range of training in diverse skill areas. These include Computer Science, Networking & Systems Security, Software Engineering, Tele-communications Technology, Multi-media Technology, Cosmetology & Beauty Therapy, Carpentry & Joinery, Hospitality and Catering, Welding & Fabrications, Electrical Installations & Repair Works, Fashion Designing, Agriculture, Automotive and Mechatronics, Furniture & Interior Designs, Film & TV Production, Block-laying &Concreting etc.

The VEIs admit students who have completed their basic education. While the training period is for three years, leading to the award of National Vocational Certificates (NVC), each year is awarded separately as NVC 1, NVC 2, and NVC 3, giving opportunity for exit and re-entry at each point. The IEIs, on the other hand, admit students after secondary school with a minimum of 5 O Level credits. It is for two years (full time) or three to four years (part-time), leading to the award National Innovations Diploma (NID).

In theory, the VIEs and IEIs as currently organised fit squarely into the new education structure being proposed. As noted earlier, there are only a few technical colleges in the country. Even where they exist, they are likely to be under-funded, poorly equipped and poorly staffed, with a curriculum that is frozen in time. With the privately owned VIEs and IEIs, government does not need to set up new colleges or recruit trainers. However, it would be necessary for these institutions to be evaluated to ensure that they are able to meet industry standards. At the moment, only 260 of such institutions that are accredited14. Government would need to offer a package of incentives that would stimulate greater private investment in setting up more of these institutions.

Incentivising Technical and Vocational Education Training

Government will need to provide real incentives for students to embrace TVET education. Perhaps, there is no better way to do it in the first instance than to make such education free whether it is obtained through the technical college or the VEI and the IEI.

Emerging government policy that favours some cost-sharing at the university level, matched with a corresponding introduction of TVET education is likely to slow down the demand for university education with time and therefore reduce the need to set up more universities. It is believed that the pressure on the university system is partly driven by lack of viable alternatives. The post-secondary education space in Nigeria has been too narrow, leaving learners without any real alternative to university education. A policy that mainstreams TVET education and provides real incentives for students to attend is likely to change this trend.

Communication has to be a major element of mainstreaming TVET education. Over the years, technical and vocational education training has been seen as an option only for those who are less intelligent and cannot cope with more academic-oriented secondary education. It may take a while to completely shed this stigma. However, major advocacy efforts that seek to promote and popularise TVET education will go a long way. Right from basic education level, children and parents must be made aware of the opportunities available in apprenticeship and TVET

education. Students must be given the assurance that they will learn the skills they need to succeed in life and also have opportunities for career progression.

Back to the Basics

One of the major problems with the apprenticeship programme over the years is that it is marked by poor entry-point quality. Emerging skills in every sector now requires a minimum competency in literacy and numeracy— the ability to read, write and perform basic mathematical functions. The entry-point to TVET education is set at the post-basic level because it is assumed that children would have acquired the basic cognitive skills to be able to learn and progress in their career of work or future education. Sundry reports have however shown that majority of those completing basic education in Nigeria are not able to achieve these basic skills that other countries embracing TVET education are able to take for granted.15This opens up a new area of challenge that must be tackled if the desired goal of the new skills-based education system must be met.

Summary of Recommendations

- Comprehensive reform of the education system to provide for multiple pathways for entry and exit between work and education.

- The 6-3-3-4 education system (or the 9-3-4 system as later adapted) needs to be reviewed. After the compulsory nine years of basic education, the senior secondary school should be only for two years with the 3rd year made compulsory only for those who intend to proceed directly to university/polytechnic. This should be known as the matriculation year. The pathway to branch off into technical and vocational training must be strengthened.

- TVET education must be integrated into the mainstream of Nigeria’s education system and no longer framed as alternative only to less academically-inclined children.

- The current system for delivering TVET education in the country is chaotic and therefore incapable of delivering on the desired results. A new framework needs to be created to streamline the roles of the various actors and still allow for central coordination.

- The National Board for Technical Education should be changed to National Board for Apprenticeship and Skills to mainstream apprenticeship training as part of the overall TVET education and bring it under one roof.

- A baseline assessment of the existing training providers needs to be undertaken to identify gaps in relation to required industry standards and to ensure that interventions are tailored accordingly.

- Government should provide real incentives to the industries and businesses to play a lead role in designing the framework and standards for the new TVET education system in the country.

- TVET education should be made free initially to encourage more students.

- A major national advocacy campaign needs to be launched to promote TVET education in the country.

- Reform of basic education to improve quality needs to be prioritized to realise the potentials of TVET education.

*Bolaji Abdullahi, former minister of youth development and sports is a policy practitioner and education reform enthusiast.

[1]https://www.academia.edu/43755361/Trends_in_School_Enrolment_of_Primary_School_Education_in_Nigeria_between_1984_and_2002

[2] James S. Etim. “Education in the Middle Years/Junior Secondary Schools in Nigeria and the USA: A Comparative Analysis. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa (Vol. 16. No.2, 2014). ISSN: 1520-5509

[3]https://net.nbte.gov.ng/technical%20colleges

[4]Adesola, Akin O. “The Nigerian University System: Meeting the Challenges of Growth in a Depressed Economy.” Higher Education 21, no. 1 (1991): 121–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3447131.

[5] https://qz.com/africa/915618/only-one-in-four-nigerians-applying-to-university-will-get-a-spot

[6]https://www.myjobmag.com/blog/unemployment-statistics-in-nigeria

[7] https://www.thecable.ng/nigerians-are-formally-educated-but-informally-employed

[8]https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/more-news/569388-shortage-of-personnel-with-tech-skills-big-threat-to-58-of-businesses-in-nigeria-survey.html?tztc=1

[9]https://pmnewsnigeria.com/2015/11/07/buhari-to-revitalise-expand-vocational-training-centres-nationwide/

[10] The Bank’s Education Specialists announced a $200 million support to the FGN to improve technical/vocational education in Nigeria. https://www.thisdaylive.com/index.php/2023/01/31/world-bank-releases-200m-to-boost-vocational-education-as-itf-unveils-framework-for-apprenticeship

[11]https://independent.ng/itf-launches-framework-for-national-apprenticeship-traineeship-system/

[12]https://www.eu-gleichbehandlungsstelle.de/eugs-en/eu-citizens/information-center/vocational-training#tar-1

[13]https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/the_uk_technical_and_vocational_education_and_training_systems.pdf

[14]https://net.nbte.gov.ng/accredited%20institutions

[15]https://guardian.ng/news/75-of-nigerian-children-cant-read-simple-sentence-says-unicef/.