By Adebayo Ahmed

The current cash crunch is the dominant issue in Nigeria today. To go about their daily lives, many people all over the country are spending countless hours on never-ending queues trying to get some money, which they presumably own. With frustration building, as a result of the cash crunch as well as other issues such as the fuel crisis, the obvious question is: “what is the way forward”? Should Nigeria continue as is, hoping that people manage the suffering for real or perceived future benefits? Or do we need a course correction before the lid gets blown off completely and we find ourselves with a severe economic contraction or worse?

The currency change policy

The cash crunch can be linked directly to the policy effort of the Central Bank of Nigeria(CBN). In October 2022, the CBN announced plans to change the currency, replacing the soon-to-be-decommissioned N200, N500, and N1000 notes with new versions. Reasons given for the change ranged from fighting counterfeiting, kidnapping, corruption, money laundering and other forms of illicit financial flows. Additionally, the policy has been touted by some advocates outside of the apex bank as a tool for stopping or limiting vote buying in the upcoming elections. Although there were indirect suggestions that efforts would be made to promote digital transactions over cash going forward, there was no new and explicit statement on cash restrictions beyond what was already in place via the cashless policy when the currency change was announced last October.

Most of the reasons given for the new policy are valid. As pointed out by the CBN, the currency notes being changed had not been redesigned in over 20 years. Improving transparency through increased digital transactions has also been a longer-term goal of the CBN, and a good one too. However, some of the reasons given were on suspicious economic grounds, such as too much cash being outside the banking system. It can be safely assumed that the point of cash is for it to be in circulation and not sitting in bank vaults and that reducing money supply in general would be part of its regular monetary policy operations. Regardless, a currency change was not expected to lead to a significant cash crisis.

However, as has become clear, the actual policy being implemented was not simply a change of the currency but a sort of “demonetisation” process. The expectation of the CBN was that cash being deposited would not be withdrawn one-for-one, but that customers would adopt other non-cash systems. This cash crisis has however exposed some of the weaknesses in the policy approach.

The policy challenge and why

The first key weakness exposed is that the CBN appears to have grossly underestimated the economy’s actual cash needs. By the economy here we mean just regular people who need cash for their livelihoods on a daily basis. As most economists are aware, Nigeria is a sort of dual economy with a significant informal sector. This is important because informality and cash use tend to go hand-in-hand. How large is the informal sector? A report by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) estimated that informal activities accounted for 41.43% of all activities, or of GDP, in 2015 (https://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/download/403). The World Bank similarly suggested that up to 80.4% of employment in Nigeria in 2021 was in the informal sector (https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/publication/informal-economy). The summary is that informality in Nigeria is a norm and hence the financial needs of the informal sector, notably cash, would be just as significant.

Surveys on use of cash in the day-to-day lives of ordinary Nigerians corroborate those accounts. From the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys(MICS) published by the NBS last year, only 35.4% of women and 47.2% of men aged 15 – 49 as at 2021 had bank accounts or any other similar set up in any financial institution. The implication of this is that the non-account-holding population use/need cash to survive on a day-to-day basis. In fact, in states such as Bauchi, Jigawa, and Kebbi, less than 8% of women had bank accounts. The most popular reason given was that they did not have a stable income, and apparently they were using cash daily for survival.

The use of cash is not limited to just the lower income segment though. Another survey in 2021 by Enhancing Financial Innovation in Africa (EFINA) asked a subset of adults if they had used cash for payments in the last year. 100% said they had. Only 24% said they had used digital means for making payments in the preceding year. Similarly, 86% said they had received some income in cash in the preceding year. Only 13% said they had received income by digital means. In summary, almost all available information pointed to cash being ubiquitous in the daily life of Nigerians. The failure by the CBN to foresee this necessary cash demand means that it probably underestimated how much demand there would be for the new currency notes.

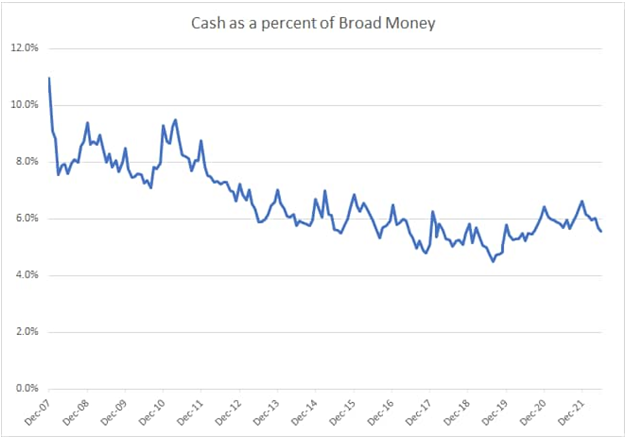

Fig 1: Cash outside depository corporations as a percent of all broad money Source: CBN Quarterly Statistical Bulletin

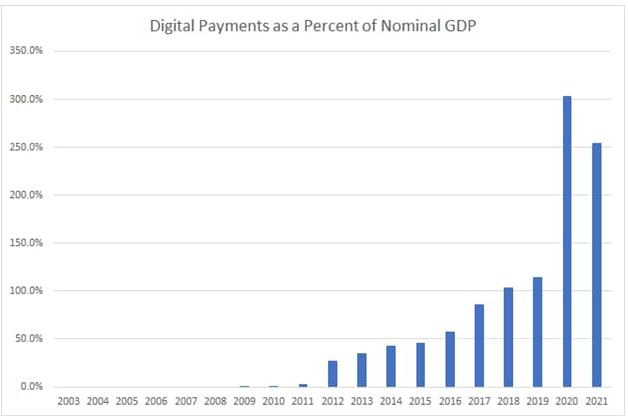

Fig 2: Digital Payments as a Percent of Nominal GDP Source: CBN Quarterly Statistical Bulletin, CBN Statistical Database, Author’s Calculations

The ubiquity of cash does not however mean that Nigeria has not made progress in the move towards a cashless economy. Indeed, due to technological innovations that have put mobile phones in almost every hand and a previously favourable policy environment by the CBN, Nigeria has made tremendous progress in digital finance as evidenced by the continued growth in digital transactions (Fig 2). Nigerian entrepreneurs continue to build innovative products that use the improved digital connectivity to provide financial services to more and more people. On a monetary policy front, cash has slowly become a smaller share of all broad money. As is clear in Fig 1, The percent of cash to all money has fallen from 11% in 2007 to about 5.6% as at June 2022. The percent of cash to GDP has similarly fallen from over 2% of GDP in 2007 to 1.67% as at the end of 2021. For context, a study by the IMF suggested that countries such as the UK, the US, China, and Japan had about 3.5%, 7.5%, 9%, and 20% currency in circulation relative to their GDP (https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/03/01/Cash-Use-Across-Countries-and-the-Demand-for-Central-Bank-Digital-Currency-46617). By all accounts, Nigeria does not appear to have a cash problem and was already moving in the digital direction even before the currency change. The problem the policy was trying to solve was not really there.

The second key weakness identified is one of unforeseen capacity constraints. On the one hand, and if unofficial information is to be believed, the Nigerian Security Printing and Minting Company Limited – the government owned corporation responsible for printing currency locally – only had the capacity to print about N200billion by the end of January 2023. A long way short of the N2.73 trillion cash in circulation as at September 2022. You do not need to solve too much mathematics here to see why there is a cash crunch. The CBN, via the NSPM PLC, just does not have the capacity to exchange all old notes for new notes even if they wanted to. The attempt by what must have been an enormous number of people looking to quickly migrate to digital platforms also appears to have overwhelmed some of the key financial institutions like NIBSS who must have had very little time to build up capacity. If the Minister of Finance was unaware of the policy in advance, as she told legislators last year, then it is fair to say the banks and associated financial institutions were also unaware.

The consequence of CBN’s failure to properly estimate cash demand, the lack of capacity to actually print new Naira notes, and the unpreparedness of the banks and associated financial institutions to handle the extra demand means that many people in Nigeria are stuck. Long queues at the ATMs that have cash to dispense. Little cash over the counter at the banks. More failures in digital transactions. As with most economic problems in Nigeria, the poor, especially women, are left bearing the short end of the stick. As is clear above, women are much more excluded from the financial systems compared to men. As we also learned during the COVID-19 pandemic, women are much more vulnerable to extra demands on their time due to cultural expectations on activities in the home.

As with other situations involving scarcity of a key commodity, some people exploit the situation for the own benefits. Various examples have been reported in the news already from bank managers looking to give cash selectively to their preferred clients and POS agent looking to make a quick extra buck from desperate customers with few other options. These are all symptoms of the cash scarcity, rather than the cause. We see these practices not only with cash but with FX and fuel. As with other instances, we can spend time and effort sending the secret police and EFCC to harass people but that will be equivalent to taking a pain killer when what you really have is malaria.

Potential outcomes with the status quo

The CBN obviously cannot print enough new currency to meet all the legitimate demand, and the financial system is struggling to cope with the increased demand for its digital services. So, what happens if we retain the status quo with continued cash scarcity? From an economic perspective, that will be tantamount to a sharp reduction in money supply which will most likely be associated with a sharp reduction in economic activity, especially in the informal sector. Sharp reductions in economic activity are typically associated with protests and in some circumstances social unrest. Just as during the COVID-19 pandemic, the how and where these will occur will always be a surprise but they tend to happen. There are some intimations of this already, from banking halls to the streets.

A second consequence of continuing with the status quo is that trust in the banking system will be eroded even more, ironically likely setting back the cashless policy. The banks, and to a large extent the whole financial system, run on trust. Trust that when you put your money in a bank you expect to get it back when you need it. The likely outcome of this cash crisis is that people seek more financial options outside the banking system to limit the risk to their livelihoods in the event something similar happens again.

Policy options going forward

Although some of the objectives of the currency change policy are laudable, the costs to the economy, especially the poor and most vulnerable, are too high to ignore. Very few people can argue against taking actions to tackle kidnappers’ use of cash or to limit the use of cash to influence elections. However, as with every policy, the benefits have to be weighed against the costs. When this cash crisis is combined with the fuel crisis, the already high food inflation, and a competitive election season, then the risk of a self-inflicted recession and social unrest is too high to ignore. It will be tantamount to turning up the heat under a pressure cooker that is already bursting at the seams.

One option will be to increase supply of the new notes by printing abroad. Aside other complications, this will take time and thus will not address the short-term crunch. On the basis of this, the only credible path to reducing the pressure and limiting the economic consequences with the unfortunate effect on the lives and livelihoods of the poorest, is to extend the timeline for the currency change. This should be done with a concerted effort to return some of the old notes into circulation to immediately ease the cash crunch.

If this is done with a new timeline that is far enough that most people do not fear the immediate risk of accepting the old notes, and is communicated clearly and transparently by all parties, then the cash crisis will end. Guaranteed, the reputational damage to the CBN from having to walk back on the policy will be difficult to reverse, but there is no cost-free path now. We can only choose the least costly option. And in doing that, the ego of the central bank should weigh far less than the economic, social and political costs to the entire system.